Chronicle of Higher Education: “But after a dozen years in the industry, the whining and whingeing of authors had worn me down: The conspiracy theories about how a publisher set out to ruin an author’s career by not sending his 15-year-old book to a small regional conference; the notion that a publisher sullied an author’s reputation by giving her a red cover; the complaint that there were not enough ads promoting the book (there were never enough ads); the indignation that we didn’t get the author reviewed in The New York Times, or booked on Oprah.” (via Bookninja)

Month / June 2007

Lev and Austin

From an interview with Austin Grossman: “Practically speaking my brother Lev helped see the thing to publication – he saw it in its early stages and told me it was worth finishing in the first place, which helped enormously; and he introduced me to his agent, who encouraged me and helped me find my agent. So I was enormously lucky in having someone to show the book.”

Doug Frantz Resigns from the L.A. Times

Editor & Publisher: “Los Angeles Times Managing Editor Doug Frantz has quit the paper, the newspaper announced today. In a short Web story, the paper revealed that Frantz, a former New York Times staffer, would leave July 6 after 20 months on the job.”

L.A. Observed has the memo, which reveals that Frantz will be heading to Istanbul to do more reporting. Was this a case of Frantz trying to bring more hard journalism to the L.A. Times and being denied by top brass or Frantz simply wanting to get out of the boardroom and back into the trenches?

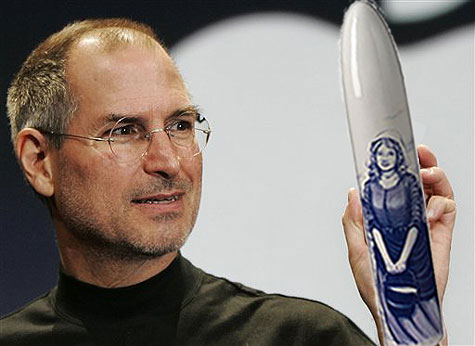

Available in Stores Today: the iDildo!

Utilizing groundbreaking iTechnology, you too can get in touch with your inner narcissist with technological options that you don’t really need. The iDildo is now available in several sizes, wherever iProducts are sold! The iDildo comes with several adjustable settings: Slow and Bored (an ideal mode for chronic time wasters), Medium Rare, and Fast and Frenetic. Optional audio settings provide you with an experience that you will never forget, better than a Sybian. Our EULA will ensure that the only orgasms you are legally entitled to experience are those effected by the iDildo, which have been perfected in our iLabs after our boys went through $200 million in R&D money. (Should you snag a lover in defiance of our terms, our attorneys will prosecute.)

We control the horizontal. And it’s all for your benefit!

Order a first-generation iDildo today for only $799! Don’t worry. We’ll work out the kinks in the next eighteen months, where the iDildo will plummet a mere $75 in price.

Roundup

- The Bay Area Intellect, a website that I was regrettably unfamiliar with when fog-drenched weather was a regular part of my daily life (as opposed to a Somerset Maugham-like tropical humidity), offers a report on the Katherine Taylor reading. Howard Junker, however, is surprisingly absent from this report. I do not know if last week’s controversy was ever resolved. Did Junker and Taylor submit to pistols at dawn and resolve this issue with the appropriate satisfaction? And can we believe that the Howard Junker now blogging at ZYZZYVA Speaks is the real Howard Junker? If Katherine Taylor was capable enough to devise a fictive Katherine Taylor, then I contend that it is equally possible that Taylor actuated a Howard Junker alter ego. Whether this Howard Junker surrogate has been programmed to tip well is something I leave the blogs to speculate over.

- A Valve correspondent investigates how descriptive language leads to personal disgust. The interesting question is whether one’s personal reaction is joined at the hip to a larger groupthink response. For example, if you or I see a steaming pile of shit being whipped up on a hot plate (and as the twisted bastard concocting this example in the early morning, I could probably go a lot further in disgusting you), then we might both agree that this is disgusting. But at what point do our individual responses relate to some conformist impulse? And is there some responsibility of the author to balance a reader’s judgment of a disgusting image with that of how far one goes in describing it? Discuss with class.

- The weather as comic strip. Another missed opportunity in perception: any real-world view of windows from another building. (via Darby Dixon)

- Reading in a Foreign Language.

- John Krasinski reads one of DFW’s “interviews.”

- Jennifer Weiner: “It took a little longer than five days, but the Times’ book blog has finally belched up its completely gratuitous Gary Shteyngart reference (if his book is just now being reviewed in England, it’s new to you!).” In defense of Garner, however, regular gratuitous references to authors (which reminds me that Matthew Sharpe’s Jamestown is much funnier than its idiot detractors* give it credit for) are what litblogs are all about.

- The Rake that is quite curious about what the Spice Girls might effect with their reunion. Yes, dear readers, I’m coming out as a closeted Spice Girls fan. It takes some astonishing moxie to pen lyrics like “Yo, I’ll tell you what I want, what I really really want / So tell me what you want, what you really really want / I’ll tell you what I want, what I really really want / So tell me what you want, what you really really want / I wanna I wanna I wanna I wanna really / Really really wanna zig-zag ha!” By my count, that’s eleven uses of “really” in one stanza. Name me another song in the history of pop music that dares to immerse itself so boldly in high school vernacular.

- Rodney Welch offers a dissenting view on The Savage Detectives. (via Dan Green)

- An ebook reader for the iPod?

- I’m not sure why this doesn’t surprise me exactly, but it appears that Michiko and Andrew Keen have locked lips. (via The Millions)

- It’s sitting in my vertiginous pile of books. So I can’t quite comment on Edward P. Jones’ editorship on New Stories from the South 2007 (and I actually have a lengthy post about Southern writers and a number of recent books I’ve read that I hope to write eventually), but Maud has an excerpt from Jones’s introduction.

- Elizabeth Hand on Rebecca Curtis.

- J. Hoberman on the CIA and the 1954 film adaptation of Animal Farm.

- To respond to Mr. Orthofer’s complaint about American coverage of Günter Grass (or lack thereof), I don’t think the fault can be leveled exclusively at the newspapers. I left about eight voicemails to set up an interview with Grass and had planned to hole up with thousands of pages of Grass before talking with him. (I did, after all, have no wish to waste the man’s time.) Not only did the publisher fail to return any of my calls (the least that could have been said was “No”), but the publisher never sent me a review copy of Peeling the Onion. Now granted, I don’t harbor any illusions that I’m entitled to any of this (and, indeed, never have). But I have a feeling that other media outlets may have received similar treatment. Ergo, the paucity of coverage.

* — By Susannah Meadows’ logic, we should discount Shakespeare’s comedies. After all, Measure for Measure is not funny in that ha-ha way and is therefore inured from exegesis. This is the attitude espoused by someone incapable of understanding the novel as nothing more than a bauble that amuses her. Which begs the question: if Meadows cannot comment properly on Jamestown‘s thematics or maintain a cogent and convincing argument, why then is she not working as a film critic for the New York Post?