(This concludes our roundtable discussion of Nicholson Baker’s Human Smoke. For previous installments: Part One, Part Two, Part Three, and Part Four.

(Many thanks to Julia Prosser at Simon & Schuster, who was kind enough to go along with this crazy idea; Nicholson Baker, for taking the time out of his busy schedule to reply to these many thoughts; and, of course, to all the participants who offered provocative and interesting insights into the book. If you’d like to discuss the book further, feel free to hash it out in the comments. And for those craving more information, there will also be a future installment of The Bat Segundo Show featuring Mr. Baker.)

Edward Champion writes:

There have been so many interesting topics raised here that I feel a bit guilty for throwing a few more talking points into the mix. Nevertheless, since we’re bringing this conversation to a close, I’m curious what you folks have to say about how Baker challenges our assumptions that World War II was the “good war” and thus the “good victory.”

There have been so many interesting topics raised here that I feel a bit guilty for throwing a few more talking points into the mix. Nevertheless, since we’re bringing this conversation to a close, I’m curious what you folks have to say about how Baker challenges our assumptions that World War II was the “good war” and thus the “good victory.”

To my mind, this issue has been germinating in Baker’s head for some time. Consider this excerpt from Baker’s last novel, Checkpoint (from pp. 61-62 in my paperback edition):

JAY: I’m on a path, man.

BEN: Well, veer off it.

JAY: There will be no veering. We’ve lost every war we’ve fought. Winning is losing. We lost the Second World War.

BEN: I think it’s widely agreed that we won World War II.

JAY: Well, we didn’t. It was the beginning of the end.

BEN: In what way?

JAY: We bombed all those places — we bombed Japan, right down to the islands, cities turned into grave sites. The crime of it began to work on us afterward, it began chewing on our spleens and rotting us out inside.

BEN: Ugh.

JAY: The guilt of it squeezed us and it twisted us and made us need to keep more and more things secret that shouldn’t have been kept secret. We tried to pretend that we were good midwestern folks, eating our church suppers — that we’d done the right thing over there. But it was so completely, shittingly false.

BEN: Yes, in a sense, but —

JAY: And so we lost that war. We didn’t win it. We were corrupted by it, and we became more and more warlike and secretive, and we spent all our money building weaponry and subverting little governments, poking here and there and propping up loathsome people, United Fruit. And the gangrene spread through the whole loaf of cheese.

BEN: Oh, please.

JAY: And Japan couldn’t do that. Their best people spent their days and nights thinking about how to make beautiful things, tools, machines that just felt good to hold. Which they did with such artistry. They couldn’t make fighter planes, we didn’t let them. And so they won the war. We lost.

Colleen raised some very valid points, which were followed up by others, about Baker taking certain liberties with military history. But I think that ultimately this book asks us, much as the second generation Holocaust historians have done, to seriously reconsider the notion of victory, as described above by Jay, the would-be assassin of President Bush. (And I also keep thinking of Clint Eastwood’s pair of films released a few years ago, which likewise presented war as a scenario in which there were no clear winners or losers.) The fact that Jay is absolutist, even in his insistence that America has lost every war, is just as egregious as claiming that, outside of Vietnam, America has won every war. War is far too complicated a beast for anyone to draw an absolutist viewpoint. And what’s more, Baker is insinuating — in both Checkpoint and Human Smoke — that this very absolutism leads quite naturally to the insanity of violence. Churchill, Roosevelt, and Hitler come off in Human Smoke as inherently absolutist and, as the closing moments of 1941 usher in further atrocities, we see that their stances become more all-or-nothing. (Likewise, this is the case with Lindbergh, whose anti-Semitism becomes more pronounced as he continues his efforts with America First, which we are reminded, on p. 348, are one of “two kinds of antiwar groups left — one on the left, and one on the right. One was made up of genuine pacifists — people from the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the Keep America out of War Congress, the Quakers, the peace ministers and rabbits, John Haynes Holmes and the Gandhians, and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. And one was made up of isolationists who, like Lindbergh and his crowds of America Firsters, liked big armies and fleets of warplanes, and who held — some of them — quasi-paranoid theories about Judeo-Bolshevik influence. They wanted the United States to lay off Germany because Germany was the bulwark that held back Stalin.”)

So with war, we see that not only is the very scope of freedom of expression squandered, whether this involves standing firmly against the war or going to jail for “a year and a day” for refusing to join the draft, but that, in hindering free speech, the ideologies themselves begin to lose their gradients. Dissent and disagreement is very much the bedrock on which civilization rests upon. The League of American Writers is initially pacifist, only to become more militant and thus more in line with the expected national ideology. The protests against Lord Hallifax become more extreme, with the two womens’ groups (on p. 425) that hold up over-the-top signs like REMEMBER THE BURNING OF THE CAPITOL IN THE WAR OF 1812 and proceed to throw an egg and tomato at him. Opportunities for peace are destroyed by fire and bombings, such as Quentin Reynolds’s observations, on p. 323, that “[a]ll that day I sensed a new and intensified hatred of Germany in the people of London.”

I’ll leave the question of cyclical contemporary parallels to others for the time being (to my mind, the harsh assaults against Jeannette Rankin, who was the sole Congressional Representative to vote against going to war, eerily recalled the similar outcry towards Barbara Lee’s stand in the days after September 11th), but I’m curious what your thoughts might be in relation to one remarkable moment on p. 373, in which Cardinal Clemens von Galen manages to persuade Hitler to suspend a program that had the Nazis killing off patients from mental asylums that had been viewed as ill and incurable. I was stunned by this moment. Because not only did this play with the commonplace perception of Hitler as an evil monster, but it brought to mind that, even within a totalitarian society, it is possible to invoke gradients through reason. So if this is naive thinking on Baker’s thought, von Galen, without a doubt, succeeded in preventing atrocities on a small scale. It was possible to do something. Why then were so many people content not to make the sacrifice? Is it entirely fair to consider Nazism an endgame scenario (as we see in the fates of Stefan Zweig and his wife)? Or is there some slim glimmer of possibility within the deadliest of human systems?

There are two additional points that we haven’t discussed yet: (1) the lend-lease agreement, which I think is quite important, and (2) the way that Baker juxtaposes the paucity of food given to those in Germany with the manner in which Churchill gorges on half a bottle of champagne and copious feasts on a near daily basis (and, again, the egg and tomato thrown at Hallifax suggests an almost absurdist failure on the protesters’ parts to understand that an organic projectile of prodigious supply is indeed a commodity in Europe). To deal with the first point, I was struck by the way in which the verb “lend” is twisted so that Roosevelt can provide military aid to Britain by subterfuge. Is “lending” then, in this sense, the problem? The willful capitulation of “lending a hand” in favor of a more bureaucratic appropriation? Is Baker suggesting here that, had food, supplies, and even the fuel that is shipped by sea been more fairly allocated, that none of the conflict and violence that followed would have happened? And is this really a fair and valid position?

I’m wondering if you folks have, like me, viewed your perception of Human Smoke as “veering off a path,” as reflected in the above excerpt from Checkpoint. Are humans hopelessly locked into natural cycles? And is it reasonable to assume that by considering the forgotten, the misunderstood, and indeed those who are damned for their unpopular positions — specifically, these ideological gradients — that we might reasonably prevent mass atrocities on a global scale? Naivete on Baker’s part or something to seriously consider?

Eric Rosenfield writes:

I just want to make two things clear: I agree with Colleen on most points, and I want to emphasize again that, for me at least, if Baker’s point was to convince us that the pacifists were right, he utterly failed. Let’s imagine, for a moment the alternate history Baker envisions: Churchill never comes to power in Britain. Hitler marches into Poland and conquers it, and England does not declare war despite it’s mutual defense treaty. Let’s even buy that this leads Hitler to never invade France or Russia, despite his constant talk of a “Third Reich” to rival the former German Empire and the Holy Roman Empire. He starts sending all the Jews in the Reich to Madagascar. Except the Jews, who have already had all their assets liquidated, can’t be allowed to create a powerful state there so they are carefully controlled, and Madagascar becomes something like a Jewish Indian reservation ala the Jewish Autonomous Oblast in Russia. Jews start dropping like flies from malaria and other diseases they have no defenses against, while the delighted Germans refuse them proper medical treatment or insect nets and watch the Jewish population dwindle. Perhaps there are even some rebellions and a massacre or ten.

Meanwhile, Hitler, Mussolini and Franco consolidate their power in Europe and create an oppressive, Fascist mainland that lasts for generations. Japan conquers China and completes their oppression and exploitation of the Chinese and Koreans. With these powers now entrenched the idea of toppling them through military or other means becomes less and less possible.

I still think Hitler would have moved on to France and then turned his attention and that of his allies to Russia to bring down the hated Communists, and once somebody finally developed nuclear weapons we would have had something of a Fascist-Communist Cold War, or perhaps simply Armageddon.

Either way, I don’t think that’s the world I’d want to live in. Yes, Churchill was a vicious bastard who approved of bombing and starving civilian populations. Yes many, many, people died in the course of the war. I still think it’s better than the alternative. Hitler, Mussolini, Tojo and co. had to be stopped.

Dan Green writes:

Sorry for entering the conversation so late. I’ve only just finished the book.

Many intelligent things have been said here both about Baker’s book and about WWII, so I’m not going to offer my own thoughts about all the points that have been made.

However, a few people have suggested that Human Smoke might also be about 9/11 and the Iraq War. It seems to me that it is mostly about 9/11 and the Iraq War. The negative portrayal of Churchill, for example, seems a direct response to the neocons’ veneration of him. Not only does Baker show him to be indifferent in the extreme to the consequences of his war-making–particularly the bombing of civilian areas prior to the German bombings of London–but also he shows us just why the neocons invoked his name so often–his insane belief that bombing civilian areas would make the population rise up against Hitler directly parallels their belief that tearing the hell out of Iraq would have a similar effect on the people of Iraq (which also happens to parallel their belief that immiserating the Palestinians will someday, somehow, cause them to rise up against their leaders and agree to Israel’s terms). The depiction of Churchill’s (and to some degree FDR’s) fondness for weapons of mass destruction seems a direct rebuke to the Bush administration’s insistence that WMDs just can’t be tolerated and their threatened use is a sign of “evil”. Etc.

Part of the early discussion involved whether Baker was being sufficiently “objective,” and much of the subsequent discussion has been about the degree to which Baker’s information and emphasis are correct. I have to agree with Brian that objectivity was probably the farthest thing from Baker’s mind while he was writing the book. It’s an alternative history of the lead-up to WWII (one day there will be similar book about the lead-up to the Iraq War), and while it’s important that his narrative be accurate–the people quoted actually said those things and the behavior described actually happened–it isn’t necessary that it be objective. Indeed, it wouldn’t be as good as it is (and I think it’s quite good) if it were. He wants his readers to remember his book the next time Churchill and Roosevelt are nominated for sainthood and the next time WWII is described unambiguously as the “good war.” To this extent, I think he will succeed admirably.

Brian Francis Slattery writes:

Hello all,

It’s been fantastic being involved in this discussion — thanks, everyone.

Just two things:

1. A couple of us feel that Human Smoke is either commenting on our current administration or perhaps is explicitly about our current administration. This is one of those questions where, even though Barthes has killed the author, it would be great to hear Baker’s own take on that question. To what extent is Baker encouraging us to think beyond the episode he describes? Another way to put it: If Baker wanted to write a book about the current administration, why didn’t

he, you know, just write a book about the current administration?

2. Ed asked this question earlier:

“Is it reasonable to assume that by considering the forgotten, the misunderstood, and indeed those who are damned for their unpopular positions — specifically, these ideological gradients — that we might reasonably prevent mass atrocities on a global scale? Naivete on Baker’s part or something to seriously consider?”

I would recommend to all of you an essay written by Richard Rorty called “Human Rights, Rationality, and Sentimentality,” which takes up this point in a really precise, passionate, and (to me) compelling way. He’s writing about human rights–and human rights law in particular–and the essay overflows with ideas, one after the other. But the jist of his argument (and Richard, RIP, please forgive me for this brutal summary) is that appeals to human rights grounded in rational thought don’t really work, and therefore, the current legal and philosophical strategy of human rights has become outmoded, at least as far as preventing more violence. As Rorty writes, “it is of no use whatever to say, with Kant: Notice that what you have in common, your humanity, is more important that these trivial differences [in ethnicity, race, religion, sexual orientation, what have you]. For the people we are trying to convince will rejoin that they notice nothing of the sort.”

Instead, Rorty argues, what changes minds are stories, stories that hit us emotionally, where it hurts. At the end of the essay, Rorty poses the question: “Why should I care about a stranger, a person who is no kin to me, a person whose habits I find disgusting?” For Rorty, rationality has no good answer. There is no real universality to which a moral question can appeal; philosophers after Kant, and especially Nietzsche, have seen to that. “A better sort of answer,” Rorty writes, “is the sort of long, sad, sentimental story which begins, ‘Because

this is what it is like to be in her situation–to be far from home, among strangers,’ or ‘Because she might become your daughter-in-law,’ or ‘Because her mother would grieve for her.’ Such stories, repeated and varied over the centuries, have induced us, the rich, safe, powerful people, to tolerate, and even to cherish, powerless people… [The last two hundred years of moral progress] are most easily understood not as a period of deepening understanding of the nature of rationality or morality, but rather as one in which there occurred an astonishingly rapid progress of sentiments, in which it has become much easier for us to be moved to action by sad and sentimental stories.”

This essay has kicked up a lot of dust since it was written, with people arguing for and against it. For my part, I don’t know if he’s right, but I hope he is.

Matt Cheney writes:

I’m still frantically reading the book, and am doing so while also teaching All Quiet on the Western Front to 10th graders, which is interesting to have going on in the background of my brain — but I wanted first to note that the Rorty article Brian cites is available online in the third issue of the Belgrade Circle Journal: here (the site uses frames; the direct link is here).

Also, an idea that popped into my head while reading Dan’s response and then Brian’s was: Brecht! Because this idea just occurred to me, I haven’t thought it through at all, but the connection was this — Brecht’s best and in many ways hardest-hitting plays are, I think, the ones that are set in his version of the past, not the ones that try to be contemporary. His attacks on the Nazis as Nazis were occasionally interesting, but they don’t possess half the power of plays like Galileo, Mother Courage, Good Person of Sezuan and Caucasian Chalk Circle, which all get some distance from particular contemporary events. This helps reduce the didacticism by creating resonance and a certain ambiguity — the audience has more freedom to think. (Which sometimes drove Brecht crazy, as when people started feeling sorry for Mother Courage…) (And yes, the dormant playwright in me wants desperately to turn this book into a script.)

I don’t think Baker is doing exactly that with Human Smoke, but I agree with pretty much everything Dan said about the book, and that agreement comes from feeling, as I read, that the book is a palimpsest — it wants to overlay ideas and images and words and facts onto the imagery already hardened in our brains, the stuff accumulated through years of watching TV, reading bits and pieces of articles and books, strolling through museums, etc. — so that when we encounter pictures of Churchill, for instance, or watch one of the ubiquitous WWII shows on the History Channel, we’ve got a few other particles of information rattling around in our memory, some sense that this is not all there is. Similarly, when John McCain starts comparing himself to ol’ Winnie, that comparison becomes more complex than McCain or his packagers might like it to be. Which brings us to the now of present atrocities — the things we are willing to look past, the things we don’t know, the things we assume. (Perhaps I shouldn’t even say “we”, because I expect we all look past, don’t know, and assume different things. Which, too, seems to be part of Baker’s point and technique.) All I know right now is I’m reading about the rejection of Jewish refugees, and though this is stuff I have known about for a long time, I’ve not *felt* it as vividly as I am feeling it now, here, reading Baker’s book. There are many possible reasons for that, but one of them is how he has structured and written the book. Like bursts of stinging light, inducing flashburn.

Frank Wilson writes:

I have read what other have to say about Nicholson Baker’s Human Smoke, but not before writing down my own impressions. I have no intention of doing any deep research into the history of World War II, but I have taken the trouble to make sure that my memory was sound regarding certain details. So here goes:

The material of the book is inherently interesting, though its presentation is not. Let us begin with the merely annoying — the repetition of phrases such as “It was March 14, 1935.” Why not just date the entries? Actually, the litany of portentous date announcements served to underscore (for me at least) the eventual monotony of merely cataloging incidents.

Which brings me to what I think is a more substantial objection: Baker’s book is a compendium of carefully cherry-picked anecdotal evidence. Having been born mere weeks before the attack on Pearl Harbor, I sort of grew up with World War II history, and I was increasingly struck, as I read Human Smoke, less by what was included — most of which I was actually familiar with — than with what was omitted. The Rape of Nanking by Japanese forces gets one entry, but the outbreak of the second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 isn’t really gone into. Hitler’s annexation of Austria and invasion of Czechoslovakia are not mentioned. Nor is the African Campaign. You would never know from this book that Germany bombed Britain for 57 straight days, starting on Sept. 7, 1940, and that the bombing continued into May of the following year. You would, on the other hand, get the distinct impression that Allied bombing of German cities left a reluctant Hitler no other choice than to bomb the hell out of Britain.

Again, no mention is made of the German-Soviet non-aggression pact, nor of the agreement between the Soviets and the Germans to partition Poland, nor of the Soviet invasion of Poland. Also unmentioned is the Tripartite Pact, according to which the Axis powers agreed that if any was attacked the others would declare war on the attacker. So we do not learn that it was Germany that declared war on the U.S., not the other way around, after the U.S. declared war on Japan following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

My point is that if you are going to let the evidence speak for itself, which I presume is the purpose of this 471-page sequence of index card-like entries, you have to present the evidence comprehensively, not so tendentiously as to render it mendacious.

Finally, there is the book’s underlying logical problem. Its premise is a counterfactual conditional proposition — if things had been done differently, the war could have been averted. Readers of Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum may recall the character who points out that the problem with a counterfactual conditional proposition is that any conclusion derived from it is correct precisely because the premise is false. If I had not written the preceding sentence, I would have …? Written another? Or none at all? And if none at all, what would I have done instead? Who knows? But you can suggest anything.

The implication of the book is that a negotiated peace was possible — if only Churchill and Roosevelt had been more tractable. The good faith of Hitler and his associates seems to be taken for granted. While it is certainly true that more could have been done on behalf of the Jewish population, the probability that a foreign policy based on the principles of the American Friends Services Committee would have had the rosy outcome Baker imagines seems to me astronomically negative.

Colleen Mondor writes:

A couple of quick points to respond to your email, Ed:

First, I guess the characters in Checkpoint were willfully ignoring the Japanese Zero? (I realize it was a novel but still…) It was an amazing technological acheivement and far out performed US fighters – until one was found and taken apart by the US resulting in the design of the Corsair. (There have even been books written about that – “Koga’s Zero” is one.) That passage raises yet another way of viewing WWII – as the Japanese as peaceful artistic people who fell prey to the bloodier crueler Western influence.

Maybe our mutual human need to see good and bad prevents us from ever considering that everybody is wrong, in one way or another, when it comes to war, period.

I think WWII is a “good” war only in a pop culture sort of way; in other words any serious study of history shows that good and bad are not words that apply to war. You can certainly find moments of “good” in any war – episodes on all sides of people going above and beyond to save others – but in terms of war itself, it is not an argument that stands up to serious scholarship. For me I was a bit perplexed by Baker’s statement that the pacifists failed. I don’t agree. I think the fact that they did speak out to such extents in WWII – when it was very difficult to do so – is impressive. They could not stop WWII – there were too many countries involved for too many different reasons – only a very strong League of Nations could have stopped it and the League was designed to be weak so it was useless. But the pacifist movement did continue to grow. Look at everything that followed – the anti war movement in the 1960s, the Civil Rights movement, the feminist movement, the marches for gay equality, etc. I think the pacifists in WWII created a map for others to follow and they deserve some credit for that. Trying to put the responsibility for the war proceeding on their backs makes as much sense as blaming it all on Churchill; and it’s just not true.

But again, Baker seems to have come to his own conclusions and presses them in the face of any evidence to the contrary.

Levi Asher writes:

First, since I think this conversation *must* be winding down eventually, I just want to say that I’ve enjoyed sharing ideas with all of you. I hope we will get a chance to do other roundtables, though I doubt we’ll often find books this incendiary (sorry) to discuss.

I wish I could respond to each person’s comments, but as Nicholson Baker might ask, “would that actually help anybody who needed help?” I don’t think it would.

I will respond to Frank’s objections to the book, though. I agree that the book presents (in its indirect, deadpan way) a very particular point of view, and is not a work of balanced history. In this sense, I do think it helps to consider Baker’s other experiments with form, like U and I, which also could not be easily categorized as any existing type of book. I think one of Baker’s goals in writing Human Smoke was to lead readers out to the edge of uncertainty about what they are reading. This is a very audacious book, and as such it is a very opinionated book. It is absolutely not an objective presentation of history, but Baker and Simon and Schuster do not seem to be trying to pretend it is.

So, if Human Smoke is just one guy’s (offensive) opinion, and if his opinions are no more persuasive than any others, then what the hell is this book good for? Well, I think Dan hits the nail on the head — I think the book is about Iraq and September 11, and about China and Darfur and Sri Lanka and Burma and Pakistan and Afghanistan. It’s a warning about our current leaders among the “global powers”, none of whom seem a whit smarter than the thugs who killed millions and millions and millions and millions in the 1940’s. And our weapons are a whole lot bigger now, so the risks have only increased for peace-loving and life-loving people everywhere.

I think this book must be taken — in its own weird way, which is the only way any Nicholson Baker book can really be taken — as a hopeful book about the present and the future. Churchill and Roosevelt take a few punches, and they’ll be fine. But this book is about the leaders we’re suffering under now, and the ones coming in next.

Robert Birnbaum writes:

The diverse and divergent views expressed here are in themselves an example of how events gain their own momentum, spinning out of control beyond the expectations of their agents. I forget the exact quote but I believe any number of senior functionaries in the first Great War were sorrowfully puzzled as to how the hostilities ended up in armed conflict. Having experienced the unimaginable losses of the War to End all Wars, I have no doubt that Europeans of all stripes were not signing up for an encore. On the other hand the incantation, “Stabbed in the back” repeated in Germany for nearly a generation —well, we saw what happened

To quote Gil Scott Heron again, “… if everybody who said they were for peace worked for peace—we’d have peace. The trouble with peace is you can’t make any money from it.”

I am a little surprised at some of the vitriol aroused by Baker’s book which I should repeat again is not a history text. That he paid scant attention to this facet of the run up or that doesn’t really matter to me. And I would expect that readers of Human Smoke would have some knowledge of that history beyond the hagiography and mythologizing that stands for history pedagogy in American public schools. My most recent chat with Howard Zinn (soon to be published) contains this:

HZ:… I am waiting for somebody to write a book about the American Revolution questioning the justice of the American Revolution. In another words, asking, “Was this really a justified war? There are there holy wars in American History—the Revolutionary, the Civil War and World War II. People are willing to say that the Mexican War was imperialist—

RB: —now they are.

HZ: That’s right. And the Spanish American War and Viet Nam. But there are holy wars. Untouchable… I think it is worth questioning the justice of those wars. It’s a complicated moral issue. You might say Vietnam is easy. Iraq is easy. And the Mexican War is easy. And there are no wars which are more morally complicated [than the three holy wars]. But the fact that they re are morally complicated wars shouldn’t stop us from examining them. The American Revolution, in terms of casualties, was the bloodiest of wars. A lot of people don’t realize that. .. and the question is, as questions in all of these holy wars, could the same objective have been accomplished, independence from England, ending slavery, defeating Fascism—could those have been accomplished at less than the bloody toll that was taken and without corrupting the moral values of the victors in the war? And with better outcomes. Those are question worth asking. The American Revolution won independence from England at the expense of the Indians, at the expense of the native Americans. The English had set a line, by the Proclamation of 1763, you couldn’t go beyond it into Indian territory. They didn’t want trouble with the Indians. Independence from England takes place, the Proclamation of 1763 is wiped out. The settlers are free to move into Indian territory. Black People—most of them joined the British side rather than the American side. It was not a revolution for them. And the question I haven’t seen asked. Canada won its independence from England without a bloody war. Conceivable? It’s like asking the question about the nature for the Civil war. Slavery was abolished in all of the countries of Latin America by 1833. Without a bloody civil war. Now, of course, all those situations are different. And complicated. All that I am saying is that I think there are questions about history that so far have been untouched and untouchable and should. At least be opened up.

At the very least that’s what Baker has done here—question the Good War. I don’t think this is a brief for pacifism and I don’t think this is vilification campaign directed at Roosevelt and Churchill. And it certainly doesn’t sugar coat the Fascist menace (remember the origin of the title?) And, by the way, the Americans showed no hesitation in [fire]bombing Japanese cities [all of which comes after the purview of the book] led by the courageous Air Force (bomb ’em back to the Stone Age) officer Curtis Le May.

As a number of people have noted they are reading Baker’s opus as a lens on our current imbroglio and, uh, leadership. Which, I think, is one of the reasons we study history. May be we will learn something from Baker’s retrospective. Maybe.

Nicholson Baker responds:

Dear Roundtablers– What’s amazing to me is that all this explicative incandescence, this un-angry criticism, this enriching supplemental observation has gone on right at the very moment Human Smoke is published. This is better than any book review, and it’s more than any writer deserves.

Dear Roundtablers– What’s amazing to me is that all this explicative incandescence, this un-angry criticism, this enriching supplemental observation has gone on right at the very moment Human Smoke is published. This is better than any book review, and it’s more than any writer deserves.

My hope in writing the book was that I could add–or overlay (as Matt Cheney puts it)–some constructive complications to our working knowledge of a disaster. It was a period that felt, to the people who were suffering through it, like the end of civilization. Stefan Zweig’s hand trembled over the page when, at the end of 1941, he thought forward to 1942, 1943 and 1944. “The precious treasure of our civilization,” wrote John Haynes Holmes just after Pearl Harbor, “is about to be swept away.” All restraints, all laws, all gentleness, all compassion, all fair dealing, all honesty, disappeared, and for five years human beings did unimaginably awful things to each other.

So I had a very simple wish: I wanted to know what terrible things happened, and what good things happened, in what order, in the earliest phases of the war, before it supposedly got really bad. I pulled many events out of their larger national or international context and looked at them as separate human decisions–because that’s what they were to their participants. That led me to what Levi Asher helpfully calls a “pointillism of fact,” and to the avoidance of fancy theories. The evidence presented in the book (as Asher also observes) contradicts itself at every turn. The war is too big and too awful to allow for summation. The first step is to allow it to fill your mind with its cries of suffering. It has to make sense as something incomprehensible. As one event follows another, the reader and the writer must participate, weigh evidence, come up with a working interpretation, refine it, reject it, recall it again, and allow it to coexist with another contradictory interpretation. This provisional theorizing on the fly is the only way to arrive at a felt understanding of what happened.

On the other hand, I needed to have threads that the reader could follow. It had to seem organizedly chaotic, not numbingly miscellaneous. That’s why I’m thrilled to read Sarah Weinman’s judgment that out of the chaos I distilled a “clear signal.” And she’s certainly right, judging by some of the reviews, that the book is a 500-page Rorschach test.

I wrote the book in a simple style for several reasons. One is that it just came out that way. Another is that I’d been reading a lot of Churchill. He’s a brilliantly florid late-night talker–full of appositions and alliterations and rhetorical figures–but all this verbal dexterity coexists with a manic bloodthirstiness of deed. The same man who can write “You do your worst, and we will do our best,” can also joke, more than once, that the British weren’t yet bombing women and children: “Business before pleasure.” Churchill’s endlessly flowing eloquence temporarily turned off my adjectival spigots, such as they are.

I did not explicitly state them in the book, but of course I have many questions and some uncomfortable (tentative) conclusions. I can’t help wondering whether some sort of negotiated ceasefire late in 1939 or in mid-1940 might have reopened western escape routes for Jews (shut down by England and France as soon as war began) and even possibly allowed for the recrudescence of more moderate factions within Germany. (I keep remembering what pacifist Frederick Libby said in his congressional testimony: that the Jews stood “a better chance of winning their rights at the conference table with Great Britain and the United States as their champions than they do on the battlefield.”) Also, I can’t help suspecting that the stepped-up British bombing campaign of 1940 and 1941–“Keep the Germans out of bed, and keep the sirens blowing,” as Lord Trenchard put it–was a gift outright to Hitler’s government, in that it helped a rage-prone, mentally ill, murderous fanatic hold on to power through five years of hell. (That’s why I quoted Shlomo Aronson, who said that the bombing offensive united Germany behind Hitler and helped him “justify further Nazi atrocities against the remaining Jews.”)

Furthermore, I can’t avoid the feeling that Herbert Hoover and his aide Alexander Lipsett were right in their charge that Churchill’s tightening of the European food blockade made him a moral participant in the deaths by famine of thousands of Jews in Polish ghettoes.

I may well be naive–as Colleen Mondor observes–in fact, as a novelist, my naivete may be one of the few strengths I can bring to the doing of history. But I don’t think that the pacifists of England and the United States were naive. I think they fully understood what was at risk. War is, as anti-interventionist Milton Mayer wrote, the essence and apotheosis of fascism. We now know that those who wanted to oppose the Hitler regime with nightly fleets of four-engine bombers were on the wrong track–the result was a very long war in which six million Jews died and the ancient cities of Europe were laid waste. The military option was tried and it worked out mind-bogglingly badly. Is it so naive to think that in 1939 and 1940 negotiation and ceasefire–a physical but not a mental capitulation to

Hitler’s invading armies–might have saved an enormous number of lives?

I’m grateful to Ed Champion for setting up this roundtable, and to you all for giving my book such careful attention.

FRIDAY A.M. ADDENDUM:

Frank Wilson responds:

Hope I can get these some what random thoughts in under the wire.

First, I thought it really gracious of Baker himself to contribute and I have to say that I agree with him that this is better than any book review. Like the book or not, agree with it or not, you cannot deny that the book prompts reflection.

Next, I want to address a phrase that you used, Ed – “the insanity of violence.” I’m not sure violence is necessarily insane, though you have to have direct experience of it to understand that. A person I was having a disagreement with and I once went crashing through a second-floor hallway banister onto the first floor below, just like in the Westerns. The actual, disturbing fact is that violence can be quite exhilarating. Thanks to the adrenaline rush, you don’t really feel any pain until the next day and you’re terrifically wide awake. In a way you feel more alive than at other times. This ought to be taken into into consideration when reading a book like Human Smoke, because one of the reasons WWII is thought have been a “good war” is that the well-nigh universal sense of urgency seemed to give everyone a heightened sense of purpose, something like the focusing of the mind that prospect of the hangman confers. Even as a small child I could sense this, and the years immediately following the war still have for me – as they do for others I know who were kids then – a brightness and optimism I have never noticed again.

As to whether a negotiated settlement would have had the salutary effect Baker thinks it might have, well, maybe if Hitler had been admitted to the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna everything would have turned out differently.

Thanks very much for extending to me the privilege of joining in on this discussion.

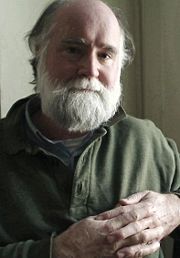

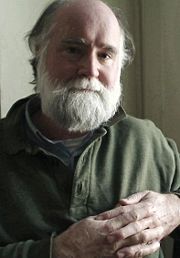

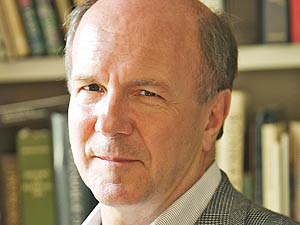

Baker was soft-spoken, effusive with his hands, and sometimes quietly gushed, particularly when talking about the “lush, colorful” nature of the New York World, one of the early 20th century newspapers that had been in his prodigious collection. Winchester was often sharp and crisp with his questioning, exuding the aura of a fussy countertenor waiting for a cadre choristers to marvel upon his ostensible magnificence, but he was good enough to point out that it was “Nick’s night.” At one point, Winchester poured water only into his glass. Baker, by contrast, filled both his own glass and Winchester’s. Winchester kept his gaze upon Baker throughout the conversation, rarely glancing to the audience. Baker, by contrast, regularly opened himself to the audience when expressing himself.

Baker was soft-spoken, effusive with his hands, and sometimes quietly gushed, particularly when talking about the “lush, colorful” nature of the New York World, one of the early 20th century newspapers that had been in his prodigious collection. Winchester was often sharp and crisp with his questioning, exuding the aura of a fussy countertenor waiting for a cadre choristers to marvel upon his ostensible magnificence, but he was good enough to point out that it was “Nick’s night.” At one point, Winchester poured water only into his glass. Baker, by contrast, filled both his own glass and Winchester’s. Winchester kept his gaze upon Baker throughout the conversation, rarely glancing to the audience. Baker, by contrast, regularly opened himself to the audience when expressing himself. When I interviewed Mr. Winchester in late 2006,

When I interviewed Mr. Winchester in late 2006,  Thankfully, none of this has stopped litbloggers from committing these energies on their own sites — see, for example,

Thankfully, none of this has stopped litbloggers from committing these energies on their own sites — see, for example,  The story, of course, was “The Sentinel.” And I read it all in one gulp. I took to craning my head out the window late at night when nobody was looking, spying during hours when nobody knew I was awake. And I did catch a pockmarked indentation, wondering if this was indeed the Mare Crisium. (A later look at a picture book on the moon confirmed that this wasn’t quite the case. But I took to calling any detail I could see a Sea of Crises, for reasons that were comical to me.)

The story, of course, was “The Sentinel.” And I read it all in one gulp. I took to craning my head out the window late at night when nobody was looking, spying during hours when nobody knew I was awake. And I did catch a pockmarked indentation, wondering if this was indeed the Mare Crisium. (A later look at a picture book on the moon confirmed that this wasn’t quite the case. But I took to calling any detail I could see a Sea of Crises, for reasons that were comical to me.) It’s become pretty hip these days to put the hate on Prozac. The drug has been accused of causing

It’s become pretty hip these days to put the hate on Prozac. The drug has been accused of causing  Palestrant enjoys “mentally instructing” Pretzel: “Be receptive to new ideas, Pretzel. Transcend boundaries. Try this new doggie biscuit.” At first I thought maybe the author was intentionally using Pretzel as a lens to examine her own thoughts and fears about immigrating. But nothing so subtle is going on; she is doing exactly what she says she’s doing: mentally instructing her dog. And the author appears to be writing with complete seriousness, “I enjoy communicating with Pretzel because he is a listener.”

Palestrant enjoys “mentally instructing” Pretzel: “Be receptive to new ideas, Pretzel. Transcend boundaries. Try this new doggie biscuit.” At first I thought maybe the author was intentionally using Pretzel as a lens to examine her own thoughts and fears about immigrating. But nothing so subtle is going on; she is doing exactly what she says she’s doing: mentally instructing her dog. And the author appears to be writing with complete seriousness, “I enjoy communicating with Pretzel because he is a listener.” There have been so many interesting topics raised here that I feel a bit guilty for throwing a few more talking points into the mix. Nevertheless, since we’re bringing this conversation to a close, I’m curious what you folks have to say about how Baker challenges our assumptions that World War II was the “good war” and thus the “good victory.”

There have been so many interesting topics raised here that I feel a bit guilty for throwing a few more talking points into the mix. Nevertheless, since we’re bringing this conversation to a close, I’m curious what you folks have to say about how Baker challenges our assumptions that World War II was the “good war” and thus the “good victory.”  I dithered on whether to bring the book with me on my trip, and decided to leave it at home, so I don’t have the dog-eared page references handy. First with the quick thoughts, then with the rant:

I dithered on whether to bring the book with me on my trip, and decided to leave it at home, so I don’t have the dog-eared page references handy. First with the quick thoughts, then with the rant: In regards to Perry and Japan – yes, I agree that the clash of West and East in Asia in the late 19th century had a huge impact on the rise of militarism in the Japanese government. The development of colonies in China affected Japanese concerns about Asian independence (for those of you wondering about the Vietnam War, it all starts with France moving into Vietnam during this period of rampant colonization.) But I don’t like to shed blame on America for Japan’s actions or Britain for Germany’s actions – I think in a lot of ways what we saw in WWII was an immense clash of titans…it is almost like the conflicting demands for power on the part of multiple countries around the world (what was Italy’s grab for Ethiopia except a desire to have a colony of its own?) forced an armed conflict. The only thing that could have stopped this (in my opinion) is a viable, reasonable treaty in 1919 and a strong and meaningful League of Nations. The world was not ready for that however, and we missed our chance.

In regards to Perry and Japan – yes, I agree that the clash of West and East in Asia in the late 19th century had a huge impact on the rise of militarism in the Japanese government. The development of colonies in China affected Japanese concerns about Asian independence (for those of you wondering about the Vietnam War, it all starts with France moving into Vietnam during this period of rampant colonization.) But I don’t like to shed blame on America for Japan’s actions or Britain for Germany’s actions – I think in a lot of ways what we saw in WWII was an immense clash of titans…it is almost like the conflicting demands for power on the part of multiple countries around the world (what was Italy’s grab for Ethiopia except a desire to have a colony of its own?) forced an armed conflict. The only thing that could have stopped this (in my opinion) is a viable, reasonable treaty in 1919 and a strong and meaningful League of Nations. The world was not ready for that however, and we missed our chance. First, I came to Human Smoke with no pro- or anti- Baker pov. I enjoyed Double Fold and that was the last Baker book I read – so I can’t speak to whether or not this is a response to any of his books.

First, I came to Human Smoke with no pro- or anti- Baker pov. I enjoyed Double Fold and that was the last Baker book I read – so I can’t speak to whether or not this is a response to any of his books.  Nearly everyone I’ve talked with about Human Smoke has insisted that it’s a departure for Baker. And I apologize, noble group. They came for my views and I DID speak out! (Apologies to Pastor Niemoller.) But aside from the lack of exuberance and perverse wordplay (no “assive-aggressive” here!), I don’t necessarily think this is the case. There is certainly Baker’s concern for details here. And when I consider that moment in The Fermata when we learn that Department of Defense funding is behind that bizarre sex laboratory or the humane qualities of the Death Watch Beetles parable in The Everlasting Story of Nory, I have a suspicion that Baker’s contextual and pacifistic sentiments have been building up for some time. Perhaps even before the Bush II administration. (And I’ll leave the theory over whether Human Smoke is, in some sense, a response to the hostile reception to Checkpoint for another to explore.) Consider also also Baker’s essay, “Clip Art” (contained in The Size of Thoughts), in which Baker responds to Stephen King’s charge that Vox was a “meaningless little finger paring” by pointing out that Allen Ginsberg had sold a bag of facial whiskers to Stanford and that, therefore, parings could not be “brushed off as meaningless.”

Nearly everyone I’ve talked with about Human Smoke has insisted that it’s a departure for Baker. And I apologize, noble group. They came for my views and I DID speak out! (Apologies to Pastor Niemoller.) But aside from the lack of exuberance and perverse wordplay (no “assive-aggressive” here!), I don’t necessarily think this is the case. There is certainly Baker’s concern for details here. And when I consider that moment in The Fermata when we learn that Department of Defense funding is behind that bizarre sex laboratory or the humane qualities of the Death Watch Beetles parable in The Everlasting Story of Nory, I have a suspicion that Baker’s contextual and pacifistic sentiments have been building up for some time. Perhaps even before the Bush II administration. (And I’ll leave the theory over whether Human Smoke is, in some sense, a response to the hostile reception to Checkpoint for another to explore.) Consider also also Baker’s essay, “Clip Art” (contained in The Size of Thoughts), in which Baker responds to Stephen King’s charge that Vox was a “meaningless little finger paring” by pointing out that Allen Ginsberg had sold a bag of facial whiskers to Stanford and that, therefore, parings could not be “brushed off as meaningless.”

Two movies opening today have me concerned about the way that contemporary cinema is avoiding authenticity in an age of wartime. If we accept the idea that a movie is, in some sense, an entertainment, then should not the entertainment at least be authentic in some sense? I think of films like My Man Godfrey, The Lady Eve, and It Happened One Night, all outstanding examples of the screwball comedy. I don’t think it’s an accident that the screwball comedy emerged from the residue of the Great Depression and continued on roughly until America became involved in the war. My Man Godfrey offers a wonderful performance by William Powell as the besotted man taken up by Carole Lombard in a scavenger hunt. What Lombard doesn’t realize is that Powell, the ostensible freeloader, is quite loaded. And Lombard’s assumptions about socioeconomic status mirror the class mobility that was very much a reality in 1936. The Lady Eve, written and directed by the great Preston Sturges, likewise plays with issues of class and very much concerns itself with a milquetoast (Henry Fonda), who must find a way to embrace the realities of fortune hunter Barbara Stanwyck. I’ve always thought that Fonda, to some degree, reflected how America was concerning itself with events unfolding in Europe. After all, much of the action takes place on an ocean liner. And Fonda’s diffident spirit seemed to reflect America’s unwillingness to get involved with events across the pond. Then there’s 1934’s It Happened One Night, in which how one survives becomes a running comic theme, as in

Two movies opening today have me concerned about the way that contemporary cinema is avoiding authenticity in an age of wartime. If we accept the idea that a movie is, in some sense, an entertainment, then should not the entertainment at least be authentic in some sense? I think of films like My Man Godfrey, The Lady Eve, and It Happened One Night, all outstanding examples of the screwball comedy. I don’t think it’s an accident that the screwball comedy emerged from the residue of the Great Depression and continued on roughly until America became involved in the war. My Man Godfrey offers a wonderful performance by William Powell as the besotted man taken up by Carole Lombard in a scavenger hunt. What Lombard doesn’t realize is that Powell, the ostensible freeloader, is quite loaded. And Lombard’s assumptions about socioeconomic status mirror the class mobility that was very much a reality in 1936. The Lady Eve, written and directed by the great Preston Sturges, likewise plays with issues of class and very much concerns itself with a milquetoast (Henry Fonda), who must find a way to embrace the realities of fortune hunter Barbara Stanwyck. I’ve always thought that Fonda, to some degree, reflected how America was concerning itself with events unfolding in Europe. After all, much of the action takes place on an ocean liner. And Fonda’s diffident spirit seemed to reflect America’s unwillingness to get involved with events across the pond. Then there’s 1934’s It Happened One Night, in which how one survives becomes a running comic theme, as in  But I felt as if this film’s energy didn’t so much originate from its human moments, as it did its rampant concern for chasing nostalgia. This is evident through the film’s showy performances that are less designed with characterization and more designed with approximating screwball comedy conventions. (It doesn’t help that the great character actress Shirley Henderson, reduced here to robotic snaps of the head and her lovely voice reduced to two shrill notes, is more or less wasted as an embittered socialite.) The film relies too much on obvious gags, such as the “boy” upstairs who must be woken up, who is not some unruly tot, but actually one of Adams’s lovers. (Witness too how this setup is based around a contrived and entirely predictable irony, in which the characters are not allowed a whit of spontaneity.) It relies very much on coincidental run-ins. There are forced double entendres, such as Ms. Adams’s “There’s something so sensual about fur next to the skin,” which she manages to make work. But more attention has been devoted to sweeping pans of parties and the crazed curve of Adams’s hat. In short, the technical outweighs the human. Which likewise involves keeping Adams’s nudity constantly covered by towels and other obstructions for the obligatory PG-13 rating. (For those who detect the whiff of prurience with this allegation, I am, like any red-blooded man smitten by a striking actress, understandably curious. But I register this charge because I am disheartened by films that wish to suggest that a woman would, in the company of another woman, constantly hold up her towel in a convenient and preordained way. We are no longer in the days when husbands and wives were depicted in double beds. This is particularly ridiculous because Adams’ character wrestles three lovers throughout the film and is by no means modest in her temperament.)

But I felt as if this film’s energy didn’t so much originate from its human moments, as it did its rampant concern for chasing nostalgia. This is evident through the film’s showy performances that are less designed with characterization and more designed with approximating screwball comedy conventions. (It doesn’t help that the great character actress Shirley Henderson, reduced here to robotic snaps of the head and her lovely voice reduced to two shrill notes, is more or less wasted as an embittered socialite.) The film relies too much on obvious gags, such as the “boy” upstairs who must be woken up, who is not some unruly tot, but actually one of Adams’s lovers. (Witness too how this setup is based around a contrived and entirely predictable irony, in which the characters are not allowed a whit of spontaneity.) It relies very much on coincidental run-ins. There are forced double entendres, such as Ms. Adams’s “There’s something so sensual about fur next to the skin,” which she manages to make work. But more attention has been devoted to sweeping pans of parties and the crazed curve of Adams’s hat. In short, the technical outweighs the human. Which likewise involves keeping Adams’s nudity constantly covered by towels and other obstructions for the obligatory PG-13 rating. (For those who detect the whiff of prurience with this allegation, I am, like any red-blooded man smitten by a striking actress, understandably curious. But I register this charge because I am disheartened by films that wish to suggest that a woman would, in the company of another woman, constantly hold up her towel in a convenient and preordained way. We are no longer in the days when husbands and wives were depicted in double beds. This is particularly ridiculous because Adams’ character wrestles three lovers throughout the film and is by no means modest in her temperament.) The Bank Job is slightly better, in part because Jason Statham is a charismatic if two-note lead and Roger Donaldson is a good enough craftsman to get some kind of performance out of the rather uninteresting Saffron Burrows, even when she beams, “I’m in a spot of bother,” to remind us heavy-handedly that we are, after all, in London. Statham, at the mercy of loan sharks, gets a lead on a bank and sets out to rob this bank in an effort to secure himself and his family for life. What makes this film work, before it drifts disappointingly into standard heist movie territory, is the intriguing way that Statham and his crew make mistakes. They haven’t committed a robbery before and they jackhammer underneath a restaurant to get to the loot, not thinking that their quite audible work is going to get them some attention. There’s a lookout man outside, but they’re all communicating through walkie-talkies on an open frequency. (This audio is intercepted by a ham radio enthusiast.) These thieves don’t know what they’re doing and, when they remain naive and clueless, this film is often gripping. And this works because these moments are human, dripping with some relative authenticity.

The Bank Job is slightly better, in part because Jason Statham is a charismatic if two-note lead and Roger Donaldson is a good enough craftsman to get some kind of performance out of the rather uninteresting Saffron Burrows, even when she beams, “I’m in a spot of bother,” to remind us heavy-handedly that we are, after all, in London. Statham, at the mercy of loan sharks, gets a lead on a bank and sets out to rob this bank in an effort to secure himself and his family for life. What makes this film work, before it drifts disappointingly into standard heist movie territory, is the intriguing way that Statham and his crew make mistakes. They haven’t committed a robbery before and they jackhammer underneath a restaurant to get to the loot, not thinking that their quite audible work is going to get them some attention. There’s a lookout man outside, but they’re all communicating through walkie-talkies on an open frequency. (This audio is intercepted by a ham radio enthusiast.) These thieves don’t know what they’re doing and, when they remain naive and clueless, this film is often gripping. And this works because these moments are human, dripping with some relative authenticity.  If you don’t know who Bill Plympton is, you’re missing out on one of the most unique independent animators now working in America. Plympton emerged into national consciousness when many of his shorts begin appearing on MTV’s Liquid TV during the late 1980s and early 1990s. This came concomitantly with success on the film festival circuit — in particular, with Spike & Mike’s Sick and Twisted Festival of Animation. But, ironically, his work has found greater appreciation outside of the States. In his own country, he’s considered more of a cult item. Which is too bad. Because if this were a just universe, Plympton would be considered a national treasure.

If you don’t know who Bill Plympton is, you’re missing out on one of the most unique independent animators now working in America. Plympton emerged into national consciousness when many of his shorts begin appearing on MTV’s Liquid TV during the late 1980s and early 1990s. This came concomitantly with success on the film festival circuit — in particular, with Spike & Mike’s Sick and Twisted Festival of Animation. But, ironically, his work has found greater appreciation outside of the States. In his own country, he’s considered more of a cult item. Which is too bad. Because if this were a just universe, Plympton would be considered a national treasure. I guess that character, who was originated in “Your Face,” was inspired a little bit by Bud Abbott on Abbott & Costello. The pencil-thin moustache guy with the suit, the slicked back hair. Kind of a sleazy salesman type guy. And that film was such a big success, such a big hit, that I continue that character on through “The Wise Man” and through “Push Comes to Shove,” and a bunch of my feature films — The Tune and Mutant Aliens and I Married a Strange Person. So those films use that character a lot. And I’ve found that he’s a very good character for laughs.

I guess that character, who was originated in “Your Face,” was inspired a little bit by Bud Abbott on Abbott & Costello. The pencil-thin moustache guy with the suit, the slicked back hair. Kind of a sleazy salesman type guy. And that film was such a big success, such a big hit, that I continue that character on through “The Wise Man” and through “Push Comes to Shove,” and a bunch of my feature films — The Tune and Mutant Aliens and I Married a Strange Person. So those films use that character a lot. And I’ve found that he’s a very good character for laughs. Plympton: A thin guy and a stockier guy. I guess that was inspired by the old Laurel & Hardy gag where they would take an egg and squash it on his head and put the hat back on. It was very dry humor. Very deadpan humor. And then that would escalate. And it escalated into, I don’t know, getting hit by a board or something like that. Well, I wanted to take that escalation and exaggerate it even more. So it becomes so violent and so surreally violent, that it’s just preposterous. And that was my initial inspiration for the film. So Alfred Hitchcock wouldn’t be someone I would say. It was more like Laurel and Hardy. Although even then, Oliver Hardy is more of a caricature than I would want to use. I brought him down as to more of a normal person than Oliver Hardy.

Plympton: A thin guy and a stockier guy. I guess that was inspired by the old Laurel & Hardy gag where they would take an egg and squash it on his head and put the hat back on. It was very dry humor. Very deadpan humor. And then that would escalate. And it escalated into, I don’t know, getting hit by a board or something like that. Well, I wanted to take that escalation and exaggerate it even more. So it becomes so violent and so surreally violent, that it’s just preposterous. And that was my initial inspiration for the film. So Alfred Hitchcock wouldn’t be someone I would say. It was more like Laurel and Hardy. Although even then, Oliver Hardy is more of a caricature than I would want to use. I brought him down as to more of a normal person than Oliver Hardy.