The Diary Junction reports that, as of tomorrow, George Orwell’s diaries will be available to the public. With the exception of a few diary entries contained in the four volume Collected Essays, Journalism, and Letters of George Orwell published in 2000 by David R. Godine, Orwell’s diaries as a whole have not been published in collected form. Like Samuel Pepys’s diary, Orwell’s diaries will be published as a daily blog. It remains unknown whether The Orwell Trust will see fit to introduce an Andrew Keen or Sven Birkerts-like antagonist who will tsk-tsk the late author from offering his work in blog form.

The Diary Junction reports that, as of tomorrow, George Orwell’s diaries will be available to the public. With the exception of a few diary entries contained in the four volume Collected Essays, Journalism, and Letters of George Orwell published in 2000 by David R. Godine, Orwell’s diaries as a whole have not been published in collected form. Like Samuel Pepys’s diary, Orwell’s diaries will be published as a daily blog. It remains unknown whether The Orwell Trust will see fit to introduce an Andrew Keen or Sven Birkerts-like antagonist who will tsk-tsk the late author from offering his work in blog form.

Month / July 2008

Bat Segundo: Technical Issues & Some Developments

Because IE and Safari users were having difficulty accessing the Bat Segundo site, I’ve temporarily disabled podPress. I’ve tested the site on Firefox, Seamonkey, IE, Safari, and Opera, and you should be able to stream the files during this transition. The podPress developer had pledged that he would fix the “Operation Aborted” problem by Sunday, but, sadly, he still has not offered an update. And regrettably, due to my failure to backup the database when caught up in the geeky excitement of upgrading, I cannot downgrade from WordPress 2.6 to 2.5 to make the current version of the plugin work.

The show is still appearing on iTunes, and you can play the shows and still download them to your iPod. But we’re not going to have specific metadata available until either (a) podPress is updated or (b) I adopt an alternative. I have momentarily activated a barebones Audio Player plugin so that those who listen to the show on the main Segundo site will be able to hear it.

For any podcasters who are currently using the podPress plugin, my advice is to not upgrade to WordPress 2.6 until the podPress developer has worked out the kinks. And for any WordPress user who is upgrading in general, be sure to make a backup of your database before you upgrade. WordPress 2.6 is experiencing problems with its image editor and several Flash-related plugins cannot operate under the current code. Since many of the plugins originate from hobbyists who are doing all this all on their free time, this creates a situation in which one must be especially cautious.

I’m going to have some additional news about the Save Segundo campaign in a few days. I am making efforts right now to keep the show running through the end of the year at its current level of prolificity. I also managed to squeeze in another eleventh-hour interview before the hiatus, which I am trying to cut down from unspecified months to a few weeks at most. The interview relates to the lexicon unveiled yesterday.

In the meantime, you can now access the show directly at http://www.batsegundo.com. I’ve also made the site W3C complaint. There will be more this week. Bear with me.

Booker Longlist

The Booker longlist has been announced. There are many predictable names, but a few surprises, including Steve Toltz and Tom Rob Smith.

Aravind Adiga, The White Tiger

Gaynor Arnold, Girl in a Blue Dress

Sebastian Barry, The Secret Sculpture

John Berger, From A to X

Michelle de Kretser, The Lost Dog

Amitav Ghosh, Sea of Poppies

Linda Grant, The Clothes on Their Backs

Mohammed Hanif, A Case of Expanding Mangoes

Philip Hensher, The Northern Clemency

Joseph O’Neill, Netherland

Salman Rushdie, The Enchantress of Florence

Tom Rob Smith, Child 44

Steve Toltz, A Fraction of the Whole

Roundup

- Hitotoki, which merges fiction with a Google Maps-like interface, has unveiled a Paris version. This website seems to me a more purposeful use of location than the steady stream of middling noir books (Wichita Noir! Peoria Noir!) from Akashic, where rough and tough regional voices who have gritty things to say about the cities they know have been overlooked by “literary” names who not only lack a feel and understanding for these locations, but who are not familiar with the most elementary components of genre. Then again, when one considers the collective hubris of Johnny Temple, a snotty dunderhead more resembling Bernard Black than Frank Black who wears the constant look of a man incapable of balancing his checkbook, and Johanna Ingalls, a dour and humorless shrew as ungrateful as a Williamsburg hipster, one is not surprised by this onslaught of mediocrity. Oh well. At least this insufferable duo publishes Elizabeth Crane and Joe Meno. Too bad they can’t be bothered to maintain the most elementary professionalism, which one finds from smarter indie houses.

- Now wait just a minute here! We’re not supposed to speak ill of the indies! The indies represent a true alternative to the corporate oligarchy that controls the publishing industry. Well, yes and no. Let us not forget that the publishing industry is a business, and that indies need to generate revenue just as much as the majors. Recall the AMS bankruptcy snafu of early 2007. The indie publishers did not control the cards. The distributor did. Indeed, AMS was unable to pay monies due to many of the publishers. Books in production had to be repackaged so that the books could sell. And while Jonathan Karp was forced to confess that indies have access to the same resources as the big boys, and that non-generic books were the wave of the future, the ability of major publishers to distribute books far and wide that keeps them ahead of the game. And the indie reliance on tenuous distribution might just have an effect sometimes on their ostensible iconoclasm. One must not necessarily judge a book by its publisher, for all publishers are beholden to the invisible thumb.

- One can have no privacy on Twitter anymore. When big publishers begin to follow your ostensibly “private” thoughts and little personal asides, the time has come to abandon Twitter. So no mas for me! It was fun while it lasted though!

- Jules Feiffer interviewed at The Onion. (via Bookshelves of Doom)

- What a load of fucking nonsense. One of the thing that distinguishes “fucking” as an adverb (and you’ll get no asterisks here from me in discussing the words; I trust readers to be adult — well, mostly adult — about cunning lingua franca) is the magical manner that it stands out without that “-ly” (in Middle English, it was “-lich(e)”) just before a modifier. English speakers, recognizing the innate dissonance of of “fucking” and “ly,” rejected “fucking”‘s deployment in our vernacular as a typical adjective converted to an adverb. Perhaps because “fucking” serves as a kind of spoken forbidden fruit, there was some compulsion to make it slightly idiosyncratic. Roy F. (“Fucking” or “Fuckingly?”) Baumeister misses the important fact that the English language is often quite flexible about converted adverbs. We can use adjectives like “slow” or “quick” and say or write that we “drove slow” or “drove slowly.” Both are acceptable adverbs and both are, suffice to say, without suffixes! Indeed, Baumeister is so unimaginative about adverbs that he hasn’t even considered the more intriguing “fuckwise” as an adverb: “fuck” as a noun and the suffix “-wise.” “Fuckwise ridiculous” doesn’t quite roll off the tongue, but it’s certainly more interesting than “fuckingly ridiculous.” But maybe there’s an adverbial application for “fuckwise” at the end of a sentence. “I was in a fucking huff” is okay. But “I was in a huff fuckwise” does not. Perhaps one should accept no substitute for “fucking.” Nevertheless, I will attempt to find usage for “fuckwise” in future posts.

The History of Verizon, Part Two (August 2000)

[EDITOR’S NOTE: This is a continuation of my ongoing history of Verizon. Part One, which covers the months of April through August 2000, can be found here. Part Three, which covers the months of September through October 2000, can be found here.]

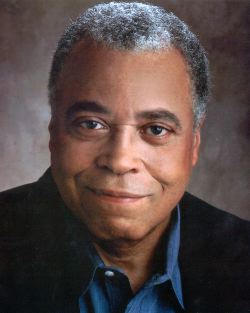

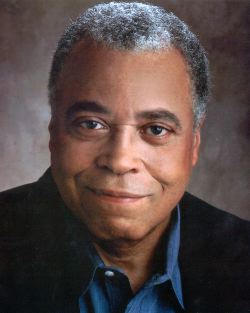

James Earl Jones, the voice of Darth Vader, became the voice of Verizon. Jones had proved popular as the voice of Bell Atlantic and his services were extended to talking up this new brand with his instantly recognizable baritone. But the Baltimore City Paper‘s Joe MacLeod was having none of this. “You never once in your whole entire life said the word, ‘Verizon,’ I’ll bet, unless you knocked back too many highballs or were wacked out on that Special K or Vitamin C or one of those other letters, but now you’re going to say ‘Verizon’ all the time like it’s a real word, and you’re going to write checks to Verizon and call Verizon, and say stuff like, ‘The goddam Verizon’s on the fritz again.’ But it’s not. There’s no such thing as a Verizon. Don’t believe James Earl Jones. It’s a made up bullshit word, and they (and you know who ‘they’ are) probably paid James Earl an ass-load of money to pitch the Verizon on the teevee.”

James Earl Jones, the voice of Darth Vader, became the voice of Verizon. Jones had proved popular as the voice of Bell Atlantic and his services were extended to talking up this new brand with his instantly recognizable baritone. But the Baltimore City Paper‘s Joe MacLeod was having none of this. “You never once in your whole entire life said the word, ‘Verizon,’ I’ll bet, unless you knocked back too many highballs or were wacked out on that Special K or Vitamin C or one of those other letters, but now you’re going to say ‘Verizon’ all the time like it’s a real word, and you’re going to write checks to Verizon and call Verizon, and say stuff like, ‘The goddam Verizon’s on the fritz again.’ But it’s not. There’s no such thing as a Verizon. Don’t believe James Earl Jones. It’s a made up bullshit word, and they (and you know who ‘they’ are) probably paid James Earl an ass-load of money to pitch the Verizon on the teevee.”

Whatever “ass-load of money” was paid to Jones, eight years later, Verizon’s name now trickles across the cochlea without cognitive dissonance, thanks in part to Jones’s efforts. The campaign, overseen by Bozell, ensured that the last dregs of Bell Atlantic would be cast asunder for this great leap forward. Jones would later use his position at Verizon to siphon off a hearty combo of Verizon and NEA money for a Magna Carta exhibit, present a $25,000 literary-tech grant to a San Ysidro school, present literary grants, and hand off awards to Russian cinematic talent. In 2002, Jones, testifying before a House Subcommittee on Education Reform, would declare, “I could not be more proud to be associated with an exceptional company like Verizon.” Even when speaking at the 2007 Buffalo Book Fair on literacy, Verizon was indelibly attached to Jones’s words.

In 2007, Jones walked away. While Jones served as a pitchman, Verizon’s contract had restricted Jones from any long-term commitments. Jones’s contract kept him off the Broadway stage until 2005. Jones, in fact, would not appear in any films between 2001 and 2004. In an interview with NWA WorldTraveler, Jones explained, “[Verizon] let me be silly for 15 years on camera — breakdancing and all that. I was as silly as I dared get. They understood that this guy usually is taken as dignified, with a big voice, so they said, ‘Let him be silly,’ and it’s worked!”

But was this really a position for an actor of Jones’s dignified stature to be in? How many dramatic presentations or Broadway performances were lost because Verizon required his services? With a strike heating up in August 2000, the Workers World News Service went further: “Who’s on the board of directors? Not James Earl Jones.” The WWNS proceeded to name names. “Your may not see these folks in the Verizon ads. You may not see their faces on your telephone bill. But these corporate interests are part of the system of exploitation that dominates our lives from telephones to political offices.”

But was Verizon really maintaining a system of exploitation? Or was it just practicing the most ruthless business practices necessary to get ahead?

With the Bell Atlantic-GTE deal receiving FCC approval, Verizon began making quiet payments to ensure its continued expansion. GTE paid $2.7 million to end an inquiry concerning allegations that it had refused to let local phone equipment in GTE offices without the construction of special facilities. Even though the FCC permitted local phone companies to place equipment at their central offices, GTE had insisted upon special equipment cages. The FCC had permitted the local phone companies to place their equipment in COs without the cages, but that hadn’t stopped the phone companies from complaining. Thankfully, money was one of those magical mechanisms that helped end such gripes.

With the Bell Atlantic-GTE deal receiving FCC approval, Verizon began making quiet payments to ensure its continued expansion. GTE paid $2.7 million to end an inquiry concerning allegations that it had refused to let local phone equipment in GTE offices without the construction of special facilities. Even though the FCC permitted local phone companies to place equipment at their central offices, GTE had insisted upon special equipment cages. The FCC had permitted the local phone companies to place their equipment in COs without the cages, but that hadn’t stopped the phone companies from complaining. Thankfully, money was one of those magical mechanisms that helped end such gripes.

Meanwhile, the forthcoming strike threatened to halt Verizon operations. More than 86,000 telephone workers from Maine to Virginia planned to walk out. On August 4, 2000, Verizon submitted a proposal to the unions. Verizon agreed that it would increase wages by 3 to 4 percent a year for union employees and improve pension plans. But with the income disparity between union and nonunion workers still unaddressed, and the details on job security and very specific demands still unclear, the unions balked. As one particularly prescient Verizon worker said, “Because the company would rather farm out work, this means one company installs the line on the outside of the building, which is us, and another on the inside, which is them. This results in a big headache for the customer, who has to be at home for two days instead of one, and a loss of income to a nonunion company.”

There are other interesting figures to consider here. In 2000, Verizon’s wireless operations generated $532 a year in revenue from each customer. A telephone company customer earned a meager $324 a year. Verizon’s wireless employees were nonunion and its telephone company employees were union, thus resulting in considerably more revenue from its wireless operations. In other words, Verizon had a vested interest in ensuring that its wireless employee basis would remain nonunion. In a competitive market and a declining economy, profit was king. And one Wall Street analyst, speaking to the New York Times under anonymity, suggested that if Verizon’s wireless unit were completely unionized, it would cost the company $300 million a year.

On August 7, 2000, with no negotiations in sight, the workers walked out. Basic services were not affected, but repairs and installations were. Verizon created a stopgap by deploying 30,000 managers — all working 12-hour shifts — to cover services that were normally performed by employees. One technician opined of the managers, “‘I think none of them are qualified to do what we do. Most of [the managers] were educated in college, but they’re not technically inclined.”

The union members were dressed in red, picketing in solidarity. One customer service reporter told the New York Times that she was “tired of being treated like a second-class citizen within the company,” but declined to give her name. Verizon had informed employees that they would be fired if they discussed joining the union at work. Most of the striking workers were former Bell Atlantic workers. The GTE units were not directly involved.

News of the Verizon strike hit many outlets, but some overlooked the company’s considerable expansive efforts. As The Motley Fool‘s Chris Rugaber reported, “While that story is important, investors interested in the telecom sector should pay just as much attention to the company’s announcement yesterday that it has already signed up 1 million long-distance customers in New York.” The company’s goal was to reach the one million mark by the end of 2000, but Verizon was five months ahead of schedule. Verizon pledged to donate $1 million to New York charities to celebrate this achievement.

By August 8, 2000, the strike had gone on for three days, with neither side coming to an agreement. “We continue to frankly plug through some of the more difficult issues that confront us,” said Verizon spokesman Eric Rabe. “It’s become sort of an intense, exhausting sort of a process.” Rabe claimed that there had been 455 acts of vandalism, violence, and harassment of Verizon managers over the previous six days. Eggs and bottles were thrown at those who crossed picket lines. Verizon offered a $250,000 reward. These acts went further. On August 8, 2000, the New York Times reported that vandals had begun slashing telephone cables in New York, causing thousands of New Yorkers to lose service. But Communications Workers of America vice president Al Luzzi declared, “We don’t condone vandalism; we never did, we never well.” Luzzi suggested that Verizon managers might be responsible for the cut cables. Nevertheless, two striking Verizon workers were nearly electrocuted when they confusedly cut through a power cable that they believed to be a phone line.

James Henry, a Bear Stearns analyst, observed that if the company could maintain service without its 85,000 employees, this would be an effective marketing tool. One that would give the company solvency, so long as the strike didn’t last beyond a week. Indeed, in the early days of the strike, Verizon customers did not experience considerable disruptions in phone service.

That same day, Verizon announced that it would be teaming up with NorthPoint to build a new broadband company. The move was on to shift broadband services to DSL. Lawrence T. Babbio, Verizon’s vice chairman and president, boasted that he was putting in 3,000 DSL lines a day. With the new company under NorthPoint’s name, Verizon was looking at a service capacity of 600,000 DSL lines. With Verizon making an $800 million investment in the new company, with $450 million of these funds allocated to network expansion and product development, NorthPoint only needed federal approval, which was expected in mid-2001. NorthPoint was an appealing acquisition because of its business customer base. Business customers could be counted upon to generate more revenue than the garden-variety consumers that Verizon had within the Bell Atlantic network.

But in November, Verizon decided to pull out. Verizon claimed that it terminated the deal because it didn’t care for NorthPoint’s deteriorating business and operating conditions. NorthPoint, counting upon the $800 million, was apoplectic. Said Liz Fetter, NorthPoint’s Communications President and CEO, “I am stunned to get the news after months of conversations with Verizon on the strong business opportunities available to the combined entities. Verizon was not entitled to terminate these agreements, and we are exploring all our options, including funding options and legal remedies.”

There was no breakup fee for terminating the deal.

NorthPoint had seen its stock decline from $39.12 a share to $2.50 a share in just under a year. The Verizon setback caused NorthPoint stock to plunge to a mere 75 cents per share. Verizon’s stock, by contrast, gained 81 cents that same day. Brown analyst Michael Bowen said to CNN, “If they lose Verizon they don’t have much of a future.” Sure enough, Bowen was right. After a round of lawsuits that NorthPoint had filed against Verizon, a NorthPoint shareholder sued NorthPoint about accounting malpractice. Because of these circumstances, 19% of NorthPoint’s workforce was laid off just before Christmas. In March 2001, NorthPoint would eventually file for Chapter 11.

Did Verizon have every intention of backing out of the NorthPoint deal? It is difficult to say with any accuracy, but I do intend to investigate this.

It should be pointed out that NorthPoint enjoyed a great success between 1999-2000, with its stock rising 68% on its first day of trading (like many dot coms) and alliances brokered with the likes of Microsoft. Led by CEO Elizabeth Fetter, a 41-year-old antique collector with a penchant for restoring historic homes, NorthPoint had relied on the Baby Bells to install DSL, but was often dissatisfied with the speed at which it could roll out its service. And although the future looked bright for NorthPoint (and fellow competitor Covad) in light of recent regulatory advantages, NorthPoint had been hit, like many, by the downturn in the economy. Verizon’s cash influx was just the kickstart that would help NorthPoint expand. But NorthPoint, expecting a fair deal, relied on the money instead of questioning it.

It should be pointed out that NorthPoint enjoyed a great success between 1999-2000, with its stock rising 68% on its first day of trading (like many dot coms) and alliances brokered with the likes of Microsoft. Led by CEO Elizabeth Fetter, a 41-year-old antique collector with a penchant for restoring historic homes, NorthPoint had relied on the Baby Bells to install DSL, but was often dissatisfied with the speed at which it could roll out its service. And although the future looked bright for NorthPoint (and fellow competitor Covad) in light of recent regulatory advantages, NorthPoint had been hit, like many, by the downturn in the economy. Verizon’s cash influx was just the kickstart that would help NorthPoint expand. But NorthPoint, expecting a fair deal, relied on the money instead of questioning it.

So why did Verizon go after NorthPoint? Did it make similar overtures to Covad? Was NorthPoint simply too hungry to expand? And why didn’t NorthPoint’s counsel ensure that the Verizon deal was airtight? Did Verizon see NorthPoint as a competitor it could whittle down? Or did it have even some intention of cooperating with Verizon all along? These questions will require investigation.

On August 9, 2000, the New York Times reported that Verizon and the unions were nearing a negotiation that “might make it easier for the unions to organize workers” at the Verizon Wireless unit. But the strike had heated up. Verizon reported 455 strike-related incidents of assault, harassment, and vandalism to the police in twelve states. With the New York summer heat rising, tempers were too. A Verizon maintenance truck run by a nonunion Verizon contractor was battered and remained stuck under a maintenance gate when a striker gained access to the gate’s remote control. New York State Supreme Court Judge Louis York granted a temporary restraining order that barred picketers from preventing workers and managers from conducting their work. Verizon increased its $10,000 bounty to $25,000.

On August 8, 2000, Verizon’s shares plunged, dropping 14%. It was Verizon’s sharpest one-day freefall since 1987. The NorthPoint deal hadn’t helped. Nor had Verizon’s bid to acquire OnePoint Communications. The terms of the OnePoint sale were not disclosed, but OnePoint was known for the DSL services it provided to apartments and office buildings in nine major U.S. metropolitan markets. Unlike NorthPoint, OnePoint had remained private.

Back on the picket lines, the struggle remained tense. 24 union members had been arrested. Waste and birdshit were tossed upon five Midtown South Precinct officers monitoring picket lines, dumped from the top of Verizon’s 41-story headquarters. The police did not plan to rule out management or strikers. And the 8,000 workers protesting outside Verizon’s headquarters participated in a rally the next day that spilled over into Bryant Park. Even presidential candidate Ralph Nader made an appearance on the Fall Churchs, Virginia picket line. Meanwhile, one advertisement featuring a Verizon worker in a hardhat with the slogan, “Bell Atlantic has a new name,” remained in circulation.

Back on the picket lines, the struggle remained tense. 24 union members had been arrested. Waste and birdshit were tossed upon five Midtown South Precinct officers monitoring picket lines, dumped from the top of Verizon’s 41-story headquarters. The police did not plan to rule out management or strikers. And the 8,000 workers protesting outside Verizon’s headquarters participated in a rally the next day that spilled over into Bryant Park. Even presidential candidate Ralph Nader made an appearance on the Fall Churchs, Virginia picket line. Meanwhile, one advertisement featuring a Verizon worker in a hardhat with the slogan, “Bell Atlantic has a new name,” remained in circulation.

Some commentators, such as the New York Times‘s Mary Williams Walsh, suggested that the customer-service complaints had become a new labor issue. Walsh pointed to Verizon’s requirement by CSRs to ask customers, “Did I provide you with outstanding service today?,” which made at least one feel like an idiot. But if the CSR did not answer the question, then a supervisor listening into the call would deduct points from the performance score. Was the burden of having to be nice all the time something to fight over? Walsh depicted the typical Verizon worker working four hours in the morning, four hours in the afternoon, with an hour off for lunch and two 15-minute breaks. But the stress arose because a supervisor kept track of every workstation using a color-coded grid. In one glance, the multihued squares would reveal whether a CSR was keeping someone on hold for too long and when a CSR signed on and off. One CSR named Patti Egan pointed out that there was only a two-second window between calls, without time to type up the order of the last caller. Often, unfinished orders were set aside, to be presumably completed during one spare two-second moment. Factor in the pressure for CSRs to upsell callers on features and the incentive for a call center to sell $60,000 worth of products a month if the CSRs want to move out of customer service and into jobs without sales duties, and the pressures that the workers were fighting for became all too clear.

By August 14, 2000, Verizon had made a new offer to the unions. But Communications Workers of America spokesman Robert Master declared it “old wine in new bottles.” But the picketeers has started to thin. The thousands of workers who had struck in the previous week had been reduced to 750. Nine days into the strike, employee Danny Marino remarked, “I didn’t think that it would come to this, definitely; I thought this would last only two or three days.” He had been married the previous month. Meanwhile, managers continued to take care of the 80,000 requests Verizon was receiving each day.

On August 16, 2000, the unions declared that they would break off negotiations with Verizon if they could not reach an agreement by midnight the next day. Mandatory overtime and job security remained the two 900 pound gorillas swinging in the room. But the next day, the workers continued talking past this deadline

As the strike took a considerable toll on Verizon’s stock share and federal rules prohibited companies from owning more than one license in a metropolitan market, Verizon unloaded wireless franchises in Chicago and Cincinnati to an investment group led by J.P. Morgan.

Finally, Verizon and the unions reached a tentative agreement. Nonunion wireless employees were permitted to organize. Two-thirds of the strikers settled on a contract two days later. The workers agreed to a three-year contract, procuring a 12% wage increase over three years. And Verizon had imposed a condition upon wireless union organization: if 55% of the employees at a work location agreed to sign cards, they’d have a union. Union telephone workers won the right to conduct more work, such as the installation of high-speed Internet lines. Mandatory overtime would be reduced, but it would still be mandatory. On the work stress issue, the unions were given five 30-minute periods each week whereby the CSRs could perform work that didn’t involve calls. But the two-second window between phone calls had gone unacknowledged.

Three years later, when the contract ran out, there would be another strike. But the next time around, Verizon would not cave. Verizon and the unions would agree to a new contract in September 3, 2003, with a one-year wage freeze, new hires not covered by the job security provisions, and one that would last five years. Five years. The precise length that Verizon had insisted in 2000. The precise length that had worried the unions because of the rapid changes in the telecom industry.

Yesterday, the New York Times reported that the unions were preparing to strike again. The numbers now? 86,000 in 2000. 65,000 in 2008. I will examine how this workforce figure was reduced and go into the 2003 strike in forthcoming installments. But for now, I’ll simply observe that the renegotiated five year contract expires on August 2, 2008. Whether the Communications Workers of America and the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers will learn a few lessons from these previous two strikes remains to be seen.