Chris Abani:

Chris Abani:

DFW was a writer’s writer in the best possible sense. His poetic sensibility with language, his keen and astute wit, and his burning sense of the malleability of form was incredible. Words like luminous, original and a deeply personal and unique style have become trite in the literary world, and yet DFW had all of this in abundance. It is not often that one can say of one’s age and career peer — I am in awe of that writer. I can say that. I will always be in awe of David Foster Wallace and I will miss him.

Mark Ames:

I never read DFW — took one look at Infinite Jest, and got turned off by all those telegraphed literary allusions and zany typefaces — gave me a nauseous feeling, like reading it would take me back to some awful Comparative Lit class, and I was going to have to pin the allusion on the reference. I hate Pynchon and never liked Joyce, so there was nothing for me. That said, now that he’s killed himself, I can’t help but have a little respect for him.

Charlie Anders:

David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest was the best science fiction novel I read in the 1990s, and remains one of the best novels I’ve ever read in the genre. The story of a future dystopia where entertainment has finally become so addictive as to be lethal, Infinite Jest was brilliant and morbid, with a bizarre suicide at its core. So maybe it’s not that surprising that David Foster Wallace took his own life this weekend. I’ve been waiting a dozen years for Foster Wallace’s next novel, and now it looks like we’re all out of luck. [More at io9]

Sacha Arnold:

When I heard he was dead, my mind zipped directly to its memories of “The Depressed Person” and “Good Old Neon” and the many other cognate points in his output. I was always awed by his compulsion to apply his analytic talents to the emotions that defeat analysis, and always figured he had thought too long and too hard about things to let those emotions defeat him. It fills me with dread to learn I was wrong.

Steven Augustine:

He wasn’t a fakir, a coward, a clone or a sell-out (while so many literary successes are all four). Sometimes he aimed preposterously high and missed, and sometimes he aimed preposterously high and hit, which is miraculous, but I’m amazed and grateful in both cases. “Little Expressionless Animals” is my “Lady with Lapdog.” I’m surprised at how upset this makes me.

Jessica Stockton Bagnulo:

My husband woke me up with the news this morning. It felt like when Elliott Smith died, or the less well-known Shannon Hoon from Blind Melon (I was in high school, and my clock radio woke me up with the news of his overdose), or Heath Ledger. The death of someone young, especially an artist, is always at first just astonishing. Michael was surprised by how fast I woke up. But this is worse than the suicide of an artist you knew was suicidal, or the OD of someone who was unsurprisingly a drug addict, or even an accidental death. That someone whose work seemed humane and, if sometimes overwhelming, not overwhelmingly bleak, seems to have had in them some kind of irresistible despair, or whatever impulse it is that leads to this — it’s incomprehensibility makes it more unbearable.

No, I never read Infinite Jest — I tried, and couldn’t make myself care enough to tackle it. But I fell in love with DFW for his work in Consider the Lobster, a recent collection of essays from magazines. It seemed to me that his expansive genius was at its best when forced to play within the parameters of length defined by something like magazine writing — he had to channel all that ambition and intelligence through a form that forced him to speak a more common language, and it made his work all the more unmistakably brilliant to have it honed down in that way. I’d never thought about grammar, or animal rights, or being a progressive in the land of Republicanism during 9/11, in a way that made my brain kindle and my compassion work overtime. I remember thinking that it must be exhausting to be this smart and multi-faceted all the time, and I was grateful to be able to engage with him one piece at a time.

Obviously the first question is why, and as usual it’s unlikely we’ll know that definitively. I keep wondering if having all that in your head all the time, that large sense of the 21st century and people’s small-mindedness and their massive greatness, would just be too much. Forgive me because I’m a comics geek, but I keep thinking of Jon J’onnz, the Martian Manhunter, who could read minds. It took incredible discipline to filter all those human thoughts into something comprehensible, and every once in a while Jon would go off the deep end from the information/empathy overload. But he was a hero, so he did his best to rein in all that he saw and knew in order to use it, and convey it, and make things happen. He made sense of the world, even when that meant articulating its senselessness. It’s a great and difficult work.

Blake Bailey:

I don’t quite know what to say about the death of David Foster Wallace, except that I wish just about anyone else on earth was dead but he. He was a compass: intellectual, moral, artistic, you name it. WWDFWD? What Would David Foster Wallace Do? I read every syllable of every footnote of Infinite Jest, first, out of a sense of obligation — this, I felt sure, was The Genius of my generation — and then because he was such excellent company. And so much fun! And such a decent, decent man. I think of his commencement address at Kenyon, reprinted in one of those Nonrequired Reading anthologies, in which he entreats his listeners, above all, simply to be kind: to put yourself in the other guy’s head, to think before you make a snide comment in the grocery checkout line, to think before you blast your car horn at someone. I remember that speech almost every day of my life, and it makes me a better person, in the tiny degrees that are the only ones that really stick.

One would think it would be great, just great, to be so brilliant, decent, and funny, but probably it was pretty hard sometimes. I think if his appearance on Charlie Rose (from, I think, 1996) that I saw recently on YouTube: Everything Wallace said seemed to coincide precisely with what he meant to say, and yet he was constantly wincing, twitching, in pain, as if a censorious little electrode in his head was punishing him, again and again and again, for not being quite worthy enough. I repeat that it must have been hard sometimes.

Christian Bauman:

In private conversations with writers and other artists I trust, I’ve been known to discuss dividing the world of novelists into two camps: those who get the joke and those who don’t get the joke. You know, “the joke.” D.F. Wallace, though, was a different stripe of cat altogether. Even saying “gets the joke” has a certain finality to it; i.e., to get the joke, the joke’s been told and done. But Wallace seemed to play on the plane of the never-ending joke. Hey, I’m not talking about the title of his novel here. Anyway. You had to walk away from your life to read Wallace, slip through the door. And you had to bring a fork. And now it seems David has slipped through the door; his method was different, but he’s laid the terrible master to waste. Poor David. His poor wife.

Alex Beam:

Alex Beam:

Uncertain what I can say, not having read his fiction. I was real admirer of his long-form non-fiction, starting with the famous cruise line story he published in Harper’s, I think. I was envious of his brilliant resurrection of discursive style, which more ordinary writers don’t really have the courage to indulge in. The grandiose, fascinating footnotes, and the confidence that his “asides” weren’t boring the reader. Ron Rosenbaum, at his best, shares a bit of this, but DFW was wonderful, I thought. He was writing in a rich tradition. Some people think Edward Gibbon was more interesting in his footnotes than in his main narration. I envied his boldness — what can I say?

Gwenda Bond:

I can’t believe David Foster Wallace is dead. I vividly remember first encountering his work in Harper’s as a teenager. Back then, Harper’s was the symbol of what I thought adulthood would be like — these were the conversations I would be in. Everyone would be as smart and funny as David Foster Wallace. And then Infinite Jest was a force of nature, pushing away the thin cynicism I found so attractive and pervasive in high school and embracing an understanding that irony and sentiment weren’t at war with each other. It changed the conversation in American letters — and it was also a great deal of fun to watch someone playing on the page and getting those results. His work never felt like work to me, not as a reader. I have always been waiting for his next great novel to come out of nowhere and surprise me all over again, and now that will never be. His voice’s absence leaves a very loud silence. My thoughts are, of course, with those who knew and loved him.

Blake Butler:

To call David Foster Wallace the greatest writer of our generation is to not quite nail it. David Foster Wallace was making something new. There was something rendered in his language that is unique to him in a way that I can not say for even any other writer. He was blessed, and apparently cursed, with massive mind. I could go on for pages about what David Foster Wallace and his work meant to my life: how he made me realize I wanted to be a writer, more so an artist; how his work fueled me through weird times in myriad ways, as a person; how his sentences embody human consciousness and our recursion; how there is nothing I know of in any art on that will match the scope of what he’s done. Beyond all of that now, is what we’ve lost here, what is gone, was one of our most dire. I can only imagine what was going through him, but I hope to dear god that he is better now, that he can rest. As for us, well, fuck; something in this world is very wrong.

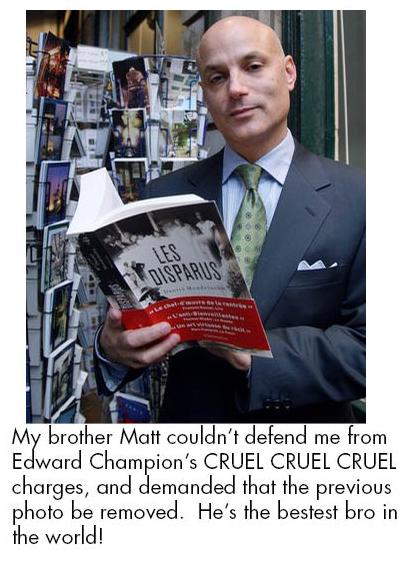

Matt Cheney:

I’m no DFW expert, not having read either of his big novels (though I’ve got Infinite Jest in hardcover, bought for $10 at The Strand in the mid-nineties, and I’ve read around in it a bit, impressed and amazed — I’ve kept it and lugged it from apartments to houses to apartments to the house I’m currently living in because it screams at me to get smarter and aim higher, to imagine more and more and more, because a doorstop can ache to be a booby trap and a universe and a mirror, and have I ever bothered to aspire for as much?), but he’s been a presence in my adult consciousness ever since, in my late teens, I read the title story in Girl with Curious Hair and laughed out tears and realized that yes there is something more to the short story biz than getting just the right formula for just-add-water epiphanies.

Honestly, he’d have wormed his way into my consciousness even if he’d never emitted anything except the phrase “a supposedly fun thing I’ll never do again”, which I have used to describe nearly every moment of my life ever since I saw the book with that title sitting on the New Books shelf at the library.

He’s the only man who ever made me buy Gourmet magazine. (And so many have tried!)

I once forced a class of high school students to read some of the “Brief Interviews with Hideous Men”. They found them deeply disturbing. “But they’re funny!” I said. “Don’t you see! They’re funny!”

I’ll confess, after a while I found his proclivity for footnotes annoying. But we all have our annoying qualities as writers and as people, and if footnotes are the most annoying thing you do, you’re less annoying than most saints. (But then, saints are annoying.) The various experiments with formatting and text didn’t annoy me; they came to be something I looked forward to with each new essay or story — what’s he going to try for this time? Just the footnotes, or something else…? So they sometimes seemed goofy or needlessly confusing. So what? Sometimes the toys I opened as a little kid on Christmas morning didn’t perform with the promised magic, but that didn’t make the opening of them any less exciting. And some of the toys, just like some of the texts, were magic.

(Sometimes I would go back and just read the footnotes. Then they were more like Christmas presents and less annoying.)

And I adored the recent Best American Essays that he edited. That anthology is so invigorating, so full of every different sort of emotion, so alive–

I guess that’s why I’m still in shock, and why this news of the person behind the initials DFW being dead is something I’m having a tough time allowing into my brain, because the sentences over which DFW is a byline so blaze with nuclear thought and joie de vivre that the fact and method of his death remains something difficult to reconcile. The writings that most impressed and stuck with me were the ones where he mixed humor and horror together, and where he dug deep into the possibilities of his ideas and words and imaginings, allowing nothing to have any single meaning or implication. Such is life. Don’t you see?

It’s time to stop now, time to go on living in a world where he’s dead, but I want him to live a bit longer, and so I’ll give him my ending with the last paragraphs of the last story in Girl with Curious Hair, “Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way”:

See this thing. See inside what spins without purchase. Close your eye. Absolutely no salesmen will call. Relax. Lie back. I want nothing from you. Lie back. Relax. Quality soil washes right out. Lie back. Open. Face directions. Look. Listen. Use ears I’d be proud to call our own. Listen to the silence behind the engines’ noise. Jesus, Sweets, listen. Hear it? It’s a love song.

For whom?

You are loved.

Elizabeth Crane:

David Foster Wallace has everything to do with everything regarding reading and writing for me. Without going into my whole life story, The Broom of the System was a book that changed everything for me. I had no idea, up to that point, what I was allowed to do as a writer, and this was a huge revelation at the time, and of course everything he wrote subsequently continued to bust the doors wide open for me. I am stunned, saddened, overwhelmed, and not understanding at all what’s just happened, and totally bereft that that next door has just been permanently sealed.

Michael Czobit:

Michael Czobit:

While David Foster Wallace gained greater fame for his fiction, his essays and reportage were the source of my admiration. Before the summer of 2006 I had heard of Wallace, but I hadn’t read any of his work. Disappointing, I know, but only more disappointing after I read Wallace’s essay, “Roger Federer as Religious Experience.”

A great accomplishment for the non-fiction writer is making a reader out of someone more likely to be a non-reader because of his lack of interest, lack of time, or lack of commitment to the words on the page. Then I was just as likely to flip the channel on a tennis match as I was to flip the page on tennis article. Coming upon Wallace’s essay, I stuck around. He started quietly but infectiously: Wallace’s admiration of the sport became mine in those first few paragraphs, bizarre as it sounds.

The further I went with Wallace, the more joy I got from him as he related his joy. It was brilliant work: in 6,500 words, Wallace converted a reader to a game he never understood. After finishing the essay, I sent the link to friends who I knew admired Federer, telling them how they would like him only more after reading Wallace’s piece.

Since that essay, I had become a guaranteed audience of Wallace’s journalism. This past June I read McCain’s Promise, which had previously been collected in Consider the Lobster and published originally in Rolling Stone during the 2000 presidential election. Wallace provided the phenomenal character study I expected. In an interview Wallace had with the Wall Street Journal about the essay, the last question had nothing to do with McCain’s Promise but a smiley face that accompanied DFW’s signature:

I have an advance copy of “Infinite Jest” that your publishing house sent me in 1996. It’s signed—apparently—by you and there’s a little smiley face under your name. I’ve always wondered—did you actually draw that smiley face?

Mr. Wallace: One prong of the Buzz plan [for “Infinite Jest”] involved sending out a great many signed first editions—or maybe reader copies—to people who might generate Buzz. What they did was mail me a huge box of trade-paperback-size sheets of paper, which I was to sign; they would then somehow stitch them in to these “special” books. I basically spent an entire weekend signing these pages. You’ve probably had the weird epileptoid experience of saying a word over and over until it ceases to denote and becomes very strange and arbitrary and odd-feeling—imagine that happening with your own name. That’s what happened. Plus it was boring. So boring, that I started doing all kinds of weird little graphic things to try to stay alert and engaged. What you call the “smiley face” is a vestige of an amateur cartoon character I used to amuse myself with in grade school. It’s physically fun to draw—very sharp and swooping, and the eyebrows are just crackling with affect. I’ve seen a few of these “special books” at signings before, and it always makes me smile to see that face.

How his words could do the same — Wallace’s better accomplishment.

Adrienne Davich:

I’m not sure how to respond to David Foster Wallace’s death, though I’m doing so anyway, as one of many profoundly moved by his fiction and journalism. Wallace got into my head, my heart, and my gut. Now, four days after September 11th and three days after his death, I keep thinking about a reading he gave a few years ago in a church in Haight Ashbury. He read his essay, “The View from Mrs. Thompson’s” — a reflection on 9/11. As my friend Ed and I glanced around the church, we were struck by the knowing looks on audience members’ faces. Had everyone read Wallace’s essay two or three times already? It seemed that way. So that particular night, Wallace’s gift for tapping into the consciousness of my generation (and the generation before mine) really hit me. Yes, there’s much to say about Wallace’s literary achievements and genius, but when I think of him now, I think first of how he evoked what it feels like to be alive in that church — to search for meaning and purpose, to endure in America today. No other writer has moved me in quite the same way.

Steve Gillis:

No one can ever really know the demons someone else is forced to live with. All we can honestly know about David is that he was a great writer, generous with his gift, an extraordinary and inimitable talent who will be greatly missed. Just last month I had reread DFW’s collection, Oblivion. The irony of the title is not lost on me now. May his soul find peace.

Tod Goldberg:

I’ve been trying to figure out for the last two days why David Foster Wallace’s death has hit me so hard. Though I met him on a couple of occasions through the years, I can’t say I knew him in the least. And though I’ve never considered myself a huge fan of his work, I’ve nonetheless read all of his books, have taught his stories and essays and always admired the fearlessness in his prose, his willingness to take whatever chance he wanted on the page. But I think there is something more at work here in my sadness for a man I never knew and wouldn’t presume to know simply by reading his work. Maybe it’s that he’s the first from what I consider my generation of writers to die and that it wasn’t by virtue of fate, but by his own hand, which makes it all the more tragic. Here was a man who wrote lucidly both about the glory and absurdity of life but also the crushing weight of depression, who had the ability to distil both hope and disconsolate sadness often in the same (very long) sentence. There is no question that David Foster Wallace was a writer of immense intellect with a gift unlike few who came before him and few who will come after him and attempt to parrot his style, though I can’t help but wonder where that style would have taken him in his later years, when the absurdity of the world he created in fiction finally caught up to real life. Or maybe that’s where he found himself already. Though it’s folly to try to make sense of chaos — he’s dead, finally, and the greatest sadness shouldn’t belong to our — my — selfish desire for more of his stories, but for his wife and his family and friends who knew him and not merely his words.

Cary Goldstein:

I didn’t know David, and I’m not equipped to comment on the breadth, scope or genius of his work. Other writers and the critics can do that. But I do know at least three NYC book editors who had, at some point, hoped to write their own novels. And then they read Infinite Jest. After that, they just couldn’t see the point.

Daniel Green:

I remember discovering David Foster Wallace’s fiction in the late 80s, specifically through Girl With Curious Hair. The book seemed to me then to introduce a new and singular voice to contemporary fiction, and I expected Wallace to produce important work extending the tradition of American experimental fiction. Infinite Jest certainly confirmed his early promise, and it is truly unfortunate we won’t be getting further work to follow up on that accomplishment. This is the loss we readers will experience most acutely, but, of course, the loss to DFW’s family, friends, and colleagues must be even more difficult to accept.

Stephanie Elizondo Griest:

David Foster Wallace was an absolute genius, whose verve and wit will be sorely missed.

Megan Hustad:

I can’t profess to understand suicide, but I know one young person who tried it and succeeded. The consensus reached by us brats who knew Mike was that his pores were cranked wide open, that he was eerily alert but that he also felt intellectually obligated, in a way few people do, to integrate everything, absolutely everything that caught his notice, into a coherent story of life on earth. And it’s not that Mike failed to do this — hell, he was only 24 — but that the story he arrived at so outraged his sense of Beauty and Truth and Justice. He couldn’t resign himself to Accommodation, any variety thereof.

When I heard of David Foster Wallace’s suicide, I opened “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again” and this is the first line of the essay, p. 258 of the hardcover, that hit:

I have felt as bleak as I’ve felt since puberty, and have filled almost three Mead notebooks trying to figure out whether it was Them or Just Me.

There’s a passage on p. 261 which I won’t retype here. What to say of David Foster Wallace’s writing? Only that among its contemporaries, it offers the most harrowing object lesson in the true costs of paying attention. Attention must be paid. Would that it didn’t hurt so.

Traver Kauffman:

DFW was a favorite of mine, and often I turned to his brilliant work to recalibrate my sense of challenging writing: the intelligent, the unexpected, the hilarious, the exasperating. Wallace’s stuff didn’t always work, but it was the real stuff.

All his intellectual knot-tying and blossoming footnotes and winking asides and plaintive fourth wall smashing seem to me to be in service of a ruthless yet open-hearted interrogation of, well, just about everything, and the loss of a writer who submits himself fully to such a rigorous pursuit is a terrible loss.

We have the all the words we are going to have from David Foster Wallace. And: No more words. But: No more words. So: No more words.

Roy Kesey:

Roy Kesey:

The first story of David’s I ever read was that one Brief Interview that he had in the Paris Review maybe ten or eleven years ago. For me it was paradigm-altering, quietly fantabulous, in exactly the way that having a clay pot broken over your head would be fantabulous if instead of dirt it turned out to be full of cocaine and Slim Jims. Of course the story stayed with me for ages; my story, “Triangulation,” which ended up finding a home in Other Voices about seven years later, surely would never have existed without it. From then on I watched him unhealthily closely, and on the days when he truly set his brain loose, there was nobody better.

Porochista Khakpour:

The way I discovered you, Edward Champion, is because of a post you made in 2006 — I believe, “Operation DFW.” This was the first post of yours that I had ever read, a post in which, miracle of miracles, YOU became ME: a bumbling hands-wringing nervous schoolgirl at the shrine of, say, the only real writer on this planet.

The thing is: I don’t think I actually ever saw him read or met him, but I feel like I have, which is a feeling I can’t quite understand.

My own Operation DFW, like all operations gloriously theoretical and functionally problematic, was going to be a good one. A couple years after DFW got his professorial post at Pomona College, my father too began to teach there. And so did Claremont siblings Harvey Mudd and Claremont McKenna. At that point I had been a rabid DFW fan for many years, certainly since the release of Infinite Jest, a novel that turned my entire world upside down and left me, later in grad school, with imitation after bad imitation of his hyperkinetic prose (this made me very unpopular and slightly reviled as one of two “metafiction kids” in a mostly Middle American realist writing program). There is no other way to put it: it was love at first sight. I was not in love necessarily with DFW or IJ, but with his prose and that had never quite happened to me like that before.

Anyway, I decided my father needed become friends with him. Never mind that DFW was in the English department and my father a professor of physics and various obscure maths. They were still colleagues in a not that huge school! Stranger things have happened. Plus DFW had an interest in math and science. He would likely appreciate my father’s eccentricities and social awkwardness, yes?

The plan became more twisted over the next few months when I persuaded my father to print out his teaching schedule at Pomona. We decided that I would drive in with my dad one day to work, say goodbye, and I’d then go to DFW’s office or classroom, and ask, with my mighty eyelash-batting and gooey-girl smile, if I could sit in on his class. Maybe for a whole semester. Until he too would fall in love. . . not with my prose (I was then back in my native California, had moved back in with my parents, was putting edits to my debut novel, and it was pretty much going disastrously to the point where I was considering scrapping it daily) but with, hell, me.

I never carried this out. I too, like you, Ed, had heard about his, er, reluctance — to put it mildly — to accept such behavior and so I stayed home, finished my novel, Googled him at least once a month, and trusted that at some point we would meet, quite certainly with me holding a shaking book and he with a poised pen, the two of us on opposite sides of a bookstore signing table.

The thing is: I have lived in many cities where he has given talks and readings, and I really cannot remember if I have seen him read. I know what he would look like, talk like, dress like, how he would read, his asides, the aftermath, everything, but I do not know how I know.

Anyway, last night, we Brooklyn writers were gathered at a dive bar after the opening gala for the Brooklyn Book Festival, and I was just leaving out the door when I saw, hours earlier, I had received the text — always the bearer of death notices these days it seems — from a friend who knew of my admiration for this man. I guess some people might have known already there, but I did not, and I fought running back and screaming into the bar, have you heard?! No, it’s not like what you all said at the speeches for this festival. Something about Brooklyn being the center of the literary universe — the real center of the literary universe was gone, poof, in some smoggy nothing college town 3000 miles away, probably just past sunset, later summer, a room, some rope, my God. . .

I went home and did all things you do when someone you don’t know, but felt like you did, dies: you look up the articles, read the blogs, and examine the freshly baked obits. Then there was the other layer of odder things you do: Google his wife, probe weather.com to find out what the world looked like to him that Friday evening (it was 76 F, a partly cloudy day, a clear night), look up when classes started at Pomona college (just 10 days before), just about anything to imagine where today’s ripples might fall.

Two weeks earlier, I had turned in my syllabus for my advanced seminar in fiction at Bucknell, which ends with some pieces from Brief Interviews With Hideous Men. I had told them point-blank that this was the only book I was pushing their way that they were not allowed to dislike.

But now I’m heartbroken and I suddenly feel like I don’t know a word he’s written. And I have to give a reading in a few hours for a celebration of books and I can’t deal with the self-congratulatory circus. I feel selfish about my sorrow: something has been taken away from me. A member of the pack has passed, a leader, a premature elder, and now all the little weak underlings — the underdogs? I am in this group — must rearrange, gather, make sense of this, and somehow move on.

The hardest part is not knowing if I had ever been in his presence at all. I blame this only partly on our modern technology to some point — all the YouTube videos and podcasts and million of articles. More than anything though, I blame his writing. Anyone who read him or who thinks the same stupid thought. He made us all the same in his shadow.

Dave King:

David Foster Wallace made reading so much fun. He was a writer I couldn’t wait to read, could never read fast enough, and can’t resist recommending to anyone who cares for the life of the written word. And yet, for all that playful innovative glory — the footnotes and lovingly tendered jargon, the typographical games and the intense punctuation and restive interjections — these are books forever rooted in something bigger than form. To read Wallace was to be stimulated by possibility, sure; but it was also to encounter a surprisingly soulful individuality and a deep and moving moral sensibility. What a profound tragedy this is.

Jennifer Matesa:

I wept when I read last night (two days after the fact) that David Foster Wallace had died. And in the past 24 hours, every time I see a picture of his face on the front page of some website, the same grief overwhelms me. Someone mentioned Heath Ledger, but that this was apparently deliberate, and that it claimed such a light in my profession, makes me feel it all the more acutely.

I taught the title essay of A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again in my advanced nonfiction course at the University of Pittsburgh in the spring semester, and my students scarfed it up, footnotes and all. One student in particular, a young man, fell head-over-heels in love with Wallace—his style and his ways of thinking about and around inside his subject; his humor and his seriousness; his flippancy and his huge heart. This student steeped himself in Wallace’s language and achieved a breakthrough in his own writing—Wallace seemed to give him permission to create a voice that was at once witty and highly intelligent, which can be such a difficult balance for a student to negotiate.

I will miss his byline.

Tom McCarthy:

Infinite Jest, along with Whatever, was the best novel of the nineties. Here was a writer really getting to grips with the shape of the world and the shapes and shapings of literature: the challenges laid down to it by information technology, corporate culture, the manifold addictions that bind us to our bodies and to one another. The essays were even better: geometry and tornadoes, craft as represented by the art of tennis, pleasure by the horror of a luxury cruise. His death (‘demapping’, as he’d say) is very sad.

Colleen Mondor:

There are a lot of things that could be written about David Foster Wallace and his amazing literary talent. I’m sure many folks will write about his fiction but I read a lot of nonfiction and it is through his essays that I am most familiar with Wallace. While I have always found them enjoyable and interesting merely on the subject matter alone, I am sure I’m not the only one who read something like “Consider the Lobster” and then spent no small amount of time wondering how the editors at Gourmet felt when the piece was submitted. It was so unexpected — such a completely off-the-wall take on a relatively bland subject — that it elevated the article far beyond its assigned intent and accomplished a great deal more than the magazine could have intended. This is what David Foster Wallace did all the time with his essays and articles and it is that complete absence of predictability that made him an author I deeply valued.

Ultimately though, what I will remember Wallace for the most is his brief but powerful contribution to the 150th anniversary issue of The Atlantic. His assertion that preserving America’s liberty demands a high sacrifice of the unorthodox kind was the patriotic call to arms that is all too infrequently found in our national discourse. He called for a national debate on issues such as Guantanamo and the Patriot Acts and he was fearless in his insistence that such debate should be part and parcel of how Americans govern.

He was fearless in so much of what he wrote and that literary bravery is what I will remember and mourn. All too often we write what we think others want to read but not David Foster Wallace; he was better than that which makes his loss all that much more acute.

Jeff Parker:

I once sent David Foster Wallace a letter. I had picked up a copy of his first novel in a used bookstore in Syracuse, NY, which contained a romantic dedication from him to a woman he’d once dated. I filled in the blanks: perhaps things hadn’t ended well. I thought that the right thing would be to send it back to him, but I also wanted to correspond with him. So instead of sending the book, I sent him a letter — this was in the just pre-email days — with some stupid thoughts of mine regarding his work and, at the end, told him about my find, quoted his dedication and offered to mail it to him. I don’t know what I expected. If he’d responded that he wanted it, I would have sent it back. But he didn’t and so I didn’t. I’ve had quite a few friends who knew him at one time or another. About half of them said he was a total dick and about half said he was the most kind, generous person they’d ever met. I don’t guess it matters one way or the other. Most people in the world would be thrilled to come up even on that count. It was only when I heard about his death tonight that I realized he’s the only person I ever wrote a fan letter to in my life.

Whitney Pastorek:

David Foster Wallace showed me how to write. Without his words, I have no idea who I’d be.

Tye Pemberton:

I am convinced that sometime during the 90’s the world became a harder place to write about. We were suddenly connected to information and to each other in ways that both empowered and alienated us and — for any writer still ambitious enough to try to gain some macro view of our world — put more responsibility on our shoulders than ever before. It seems to me that many of our best writers noticed the change, and understood how unreasonable a proposition it was. They wisely took their measures of the world in portions. David Foster Wallace, on the other hand, reacted in kind when the volume of the world increased. David Foster Wallace’s writing is, of course, all of that to me. But there is a simple element of it that makes it much, much more.

There was a story written before all that, before Infinite Jest or his two other brilliant collections of stories or his two funny, affecting volumes of essays. In Luckily the Account Representative Knew CPR two men living comparable lives descend into the basement of their office building after each man has finished a late day’s work. The older man begins to have a heart attack and the younger man begins to give him CPR and no one is coming and it is the middle of the night and keeping the other man alive is physically exhausting. And as the younger man continues to shout for help, the reader realizes that he’s not just shouting after help for the dying man, but for himself and his own responsibility to that man.

Deep down, it seemed, Wallace believed that we would help each other. In the vast, impersonal world he saw around him, the world that was sprawling every day, he still saw that our increasing disinterest in one another was an illusion, that we were still connected, as intimately with total strangers as with our loved ones. Not because the constantly new world was inherently faceless, but because we had been tasked with taking on a greater portion of the world than we could handle. It was in our natures to filter it by doing things like making strangers out of our neighbor.

David Foster Wallace seemed to believe that when it came down to it, the illusion would be ripped aside, and we would help.

But he understood so early how frightening this was — our dependancy on total strangers for nothing less than life. More than that — our responsibility to total strangers for nothing less than life.

This is what made his work sublime. Not just the heroism of taking on the screaming tidal wave of our new world, unflinchingly, but that in the end, although he may have believed we were sleepwalking, he also believed that in the moment when we woke we would do the right thing.

In a commencement address he gave at Kenyon University in 2005 he said:

The really important kind of freedom involves attention and awareness and discipline, and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them over and over in myriad petty, unsexy ways every day.

That is real freedom. That is being educated, and understanding how to think. The alternative is unconsciousness, the default setting, the rat race, the constant gnawing sense of having had, and lost, some infinite thing.

If his writing is any indication, David Foster Wallace was awake and conscious more than anyone could reasonably be asked to be. Someone had to be accountable for everything. It was a ridiculous demand. And I loved him for it.

Neal Pollack:

Neal Pollack:

What a terrible loss. Man, did I love making fun of his footnotes, but it’s hard to imagine contemporary American literature without them.

Jeff Popovich:

No scene in contemporary literature is more indelibly stamped in my mind than the Drano episode in Infinite Jest. It simultaneously reminds me of demons I fought (and fight) and beat and reminds me of how grateful I was to read it, both by expressing what I needed to hear said in the way it needed to be said and by freeing me from having to keep trying to write it myself.

Kevin Sampsell:

I was very sorry to hear about David’s death. I first saw the news on your blog and I know that you were a big fan. I never read Infinite Jest, but I did read Girl With Curious Hair around that time and I remember being blown away by the title story, about the kids frying on drugs at a Keith Jarrett concert. That story ranks right up there as my favorite stories ever (probably somewhere between a couple of Robert Coover stories). It was like Mark Leyner if Leyner were an unapologetic misanthrope. Since then I have read mostly essays from him and found his style to be like a brainiac George Plympton. The epic boat cruise piece was hilarious and his article on David Lynch was a thoughtful exploration that I also related to quite a bit at the time.

Terri Saul:

These are the things I remember first when I think of DFW:

1. When we attended the City Arts and Lectures event where Rick Moody was interviewed by David Foster Wallace in San Francisco, which was well covered here: Black Market Kidneys, Conversational Reading, and Return of the Reluctant.

My strongest memory of that evening is the sense of DFW as an engaged, morally grounded, politically opinionated and humble teacher. He mentioned his students, their quirks, their reading habits, and the character of college life a bit; the failures of the Bush administration; and other ills of the world, which made him seem like much less of a narcissist than other writers of greater fame. I had a feeling that he was a pretty altruistic educator, and that he genuinely loved working at the college. His students must be beside themselves.

2. And this from “The Nature of the Fun”:

The best metaphor I know of for being a fiction writer is in Don DeLillo’s Mao II, where he describes a book-in-progress as a kind of hideously damaged infant that follows the writer around, forever crawling after the writer (dragging itself across the floors of restaurants where the writer’s trying to eat, appearing at the foot of the bed first thing in the morning, etc.), hideously defective, hydrocephalic and noseless and flipper-armed and incontinent and retarded and dribbling cerebro-spinal fluid out its mouth as it mewls and blurbles and cries out to the writer, wanting love, wanting the very things its hideousness guarantees it’ll get: the writer’s complete attention.

The damaged-infant trope is perfect because it captures the mix of repulsion and love the fiction writer feels for something he’s working on. The fiction always comes out so horrifically defective, so hideous a betrayal of all your hopes for it -– a cruel and repellent caricature of the perfection of its conception –- yes, understand: grotesque because imperfect . And yet it’s yours, the infant is, it’s you, and you love it and dandle it wand wipe the cerebro-spinal fluid of its slack chin with the cuff of the only clean shirt you have left (you have only one clean shirt left because you haven’t done laundry in like three weeks because finally this one chapter or character seems like it’s finally trembling on the edge of coming together and working and you’re terrified to spend any time on anything other than working on it because if you look away for a second you’ll lose it, dooming the whole infant to continued hideousness). And so you love the damaged infant and pity it and care for it; but also you hate it…

John Sheppard:

When I think of DFW, I think, like most writers do, of Infinite Jest. I can’t think of a more influential novel written by someone from my little generational cohort. I think I spent two months reading it when it first came out, and maybe a year or two thinking about it. It was wonderful, sprawling, funny and ghastly all at the same time. It was perfectly imperfect.

Amy Shearn:

I’ll never forget the day I first heard of David Foster Wallace. I was a high school student in a writers group made up of employees of the public library. One night Jen, a twenty-something poet who I worshiped, brought in Wallace’s book Girl With Curious Hair. “Listen to this,” she’d said, and then she read aloud the first few pages of the title story. I can still hear her voice reading those first lines: “Gimlet dreamed that if she did not see a concert last night she would become a type of liquid, therefore my friends Mr. Wonderful, Big, Gimlet and I went to see Keith Jarrett play a piano concert at the Irvine Concert Hall in Irvine last night. It was such a good concert! Keith Jarrett is a Negro who plays the piano.”

I couldn’t get over it. I’d never heard anything like it! I thought this story was, first of all, the funniest thing I’d ever read. (I rushed out to buy my own copy of the book and devoured the stories within a couple of days.) And when I read it again, I realized that it was also terrifying, and dark, and nihilistic, and yet still hilarious. Sick Puppy’s affectless narration belies his hunger for companionship, and the relationships between the story’s cast of punkrocker misfits are as tender as they are cruel. And that language! I really had never known there was writing like this — explosively smart, unapologetically playful, frighteningly imaginative. Discovering Wallace eventually led me to Donald Barthelme and Robert Coover and other writers that made literature feel exciting and wide-open. Reading him made me feel, as a young writer, that anything was possible.

Rachel Shukert:

Another human felled by the fatal disease of having a brain too big to be viable, David Foster Wallace turned esoterica to poetry and poetry to esoterica. It’s perhaps the greatest stretch of imagination to imagine such a gloriously overloaded mind gone dark, so I won’t try to attempt it; I’ll just pretend he’s still alive.

R.U. Sirius:

I may be painting myself as a bit of a reactionary, but in an age that almost compels brevity, miscellany and minimal ambition, it’s particularly sad to lose someone who could write that infinite doorstop of a book and make it work and make it speak to a time and – in a sense that I hope isn’t too clichéd – to a generation (or a very few members of it.) I mean, he was generous but he wasn’t Whitman or even Pynchon. He was uniquely of his time.

Suicide, though, seems to be a perennial.

Christopher Sorrentino:

It does a disservice to Wallace and his work to remember it as a sustained exception to the “rule” pigeonholing postmodern work: that it is severely technical, devoted exclusively to games and to the algorithmic execution of formal steps. Time and again Wallace demonstrated that it is only through daring acts of creativity that we can be drawn into the human heart securely: via the questions he raised about the nature of storytelling; via his upending of reader’s expectations; and especially via his implicit condemnation of conventional narrative as the perfect formal delivery system for conventional wisdom. These approaches are not exceptional; rather, they go directly to the essence of the writing, and reading, experience.

It would be a further disservice if this great writer’s life, and career, were to become circumscribed, and defined, by his terrible death. Reading over the hasty hagiographic tributes which have appeared since Saturday night, many of which include ickily fannish scanning of Wallace’s works and public utterances for clues to his ultimate intentions, it seems to me that such tributes don’t appear to be the product of true “reading” at all. Wallace would have wanted such romantic horseshit shunted to the side — shredded and burned, if possible. Wallace wrote for the same reasons any writer does: to launch his preoccupations on the tar sea of composition, and to be read. That he is read, and even revered, has always struck me as a reason for hope — I gather that, tragically, it didn’t strike him the same way. Yet his output is not a 3,000 page suicide note, and even in the darkest corners of these fecund and exuberant works we can find no more evidence of the suicidally depressed individual Wallace evidently became than we can detect the impoverished and out-of-favor Mozart in his own exuberant late works.

He was the best we had. In perpetuum, frater, ave atque vale.

Dana Spiotta:

When Infinite Jest came out, I lugged that huge thing everywhere I went until I had read every word. My copy still has little yellow post-its all over it. Anyway, it’s beyond sad and I can’t say enough how much I will miss his writing. He took huge risks on the page–there was always something important at stake. Yes, he was a brilliant writer, but he was also a brave and true and deeply funny writer.

Patrick Stephenson:

When I learned DFW had died — had, worst of all, committed suicide — I was sitting on the outskirts of a large family dinner. We’d just finished eating and I’d left the table to check my e-mail and Twitter on my laptop. “David Foster Wallace dead,” I read, via Maud Newton, via Ed Champion. “Oh my god,” I said. “Oh my god.” And I began, nearly immediately, to cry. All of my family — still seated around said dinner table & in the midst of a very loud, heated argument about politics (Palin) — turned toward me. I kept on crying.

“That is just fucking awful,” I Twittered. “God dammit.”

David Foster Wallace was a genius, in the true, uncorrupted-by-Apple sense of that word. A brilliant writer with an awesomely awesome brain, but his fiction wasn’t detached or inhumane. He loved language, all kinds of language. Language that’s traditionally beautiful, and language that’s beautiful because of what it hides. The vernaculars of advertising, corporations, psychiatrists. He had mastered or could master it all. He was experimental, but not at the expense of his fiction’s humanity. And beneath his pyrotechnics, you sensed a deep and profound empathy for everyone, despite the evils we do.

(And also also, he was hilarious. I’ll be rereading the title essay of A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again till I die.)

DFW inspired me as a writer, and he inspired me as a human being. I can’t make that miserable, post-workday trip to the supermarket anymore without thinking of DFW’s commencement speech at Kenyon. I think of what he called our default setting: A self-centeredness that makes us unfairly and ignorantly despise anyone who gets in our way. Per David Foster Wallace, being truly humane ”involves attention and awareness and discipline, and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them over and over in myriad petty, unsexy ways every day.”

I left adolescence and grew into my mid-20s with David Foster Wallace, or rather, his words, at my side. I couldn’t have had a better guide, and discovered so much about the world through his writing. I learned about other writers, other artists — David Lynch, John Updike, Don DeLillo. I learned about the universality of the various pains and anxieties I’ve experienced. And I learned about compassion. David Foster Wallace succeeded at what Mr. Rogers (that Mr. Rogers, the PBS Mr. Rogers) said should be our mission as people: To remind others that they are not alone.

I hoped DFW would be at my side as I got older. More essays, more novels, more everything. I wanted it all from him. He was one of the few writers I regularly Googled, searching for new morsels. Anything he wrote, I would read. (Even if it was about Roger Federer.) No more. We’ve lost him.

If only DFW had heard and understood his own words to the suicidal protagonist of “Good Old Neon”: “It wouldn’t have made you a fraud to change your mind. It would be sad to do it because you think you somehow have to.” Suicide sucks, dude.

Katherine Taylor:

I was first introduced to DFW by a boy I had a crush on in college, who gave me a wilted Broom Of The System paperback (come to think of it, that’s the same friend who introduced me to Leonard Michaels; DFW & LM have a lot in common in the humor-grief department). There’s nothing a co-ed loves more than a book that’s impossible and funny and sad and self-conscious — a book that’s sort of the physical manifestation of a college co-ed. I wanted to write books that expansive and that human, where the pain was buried just underneath the surface, where the book seemed as alive as I was. There aren’t a lot of writers who, when you read them, make you want to write.

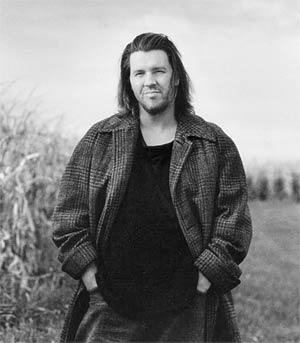

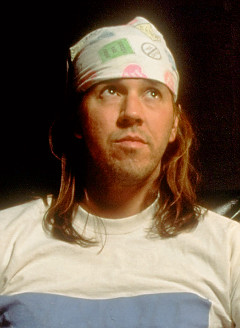

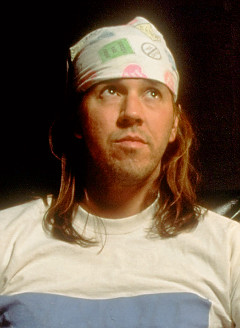

Something I’ve always felt critics (and admirers) missed in his work was the depth of the sadness. So much is made of his manic humor and irony and po-mo self-consciousness, but people rarely talk about how human and how painful his work is. In that Charlie Rose interview where he wore the bandana on his head and kept telling Charlie how stupid his questions were, DFW mentioned his disappointment or disillusionment with the reception of his work as very funny, as he’d thought it was all very sad. Probably he spoke for anyone who’s ever written a sad book interpreted by everyone as funny.

I imagine now everyone will talk about the sadness in his work, though.

Bill Tipper:

I read Infinite Jest with pleasure, frustration, awe, and the secure knowledge that I’d return more than once to the world he created, as I have. For all that Wallace was supposedly an author who exemplified postmodern fictive antics run amok, in fact I experience him as a profound counterpoint to the view that a novelist who pays attention to himself as a writer does so at the cost of exploring human connections. The creator of Don Gately and Michael Pemulis (to name just two figures who are imagined as richly as any you’d care to name in 20th-century fiction) overflowed with generosity toward his characters and his readers; if the novel they exist within seems like a baggy monster, it’s because the universe they, and we, stumble through is just as monstrous and ill-formed. For giving us that book alone, I’m sure I’m among many who feel a huge debt to the man.

This isn’t even to speak of his irreducible style as an essayist, or the fact that he’s the guy who penned the amazing short story “Little Expressionless Animals.” It’s a crushing loss for literature, for readers, and that’s simply all there is to it.

Lindsay Waters:

I am so glad you are collecting remembrances of David. Hearing more about him, remembering him, talking about him makes me feel better. It’s the only consolation that works for me. It is so weird he hangs himself when he did. He hung himself and let himself crash days before the stock market crashed. There’s something very Slothrop about this.

But let’s not forget in the moment of his death or ever that David was an advocate of a full-blooded response to life and to artworks. The way I can carry on his work is to develop and publish more books that make people feel it’s not OK to respond to life and art with a blasé snootiness. It’s our moral duty to embrace both of them and even to embrace him in death.

I had some good dealings with David in which he did not hold back his responses to life. He was a wonderful colleague for my dear friends at the Dalkey Archive Press like John O’Brien, when it was located at Normal, Illinois, just down the road from where I was raised in St. Charles. There was something militantly Midwestern about David, and that was a great thing in my eyes. Normal, IL. Normal. Illinois. Well, if you’ve read and looked at Michael Lesey’s Wisconsin Death Trip, you’ll know you ought to be a little careful if you go to my normal Illinois or David’s. But I think the Dalkey Archive people with their journals and love of strange books from France and Russia provided a wonderful environment for David. Their spirit and his seems to be that espoused by Tom Petty when he sang, “She was an American girl, raised in the provinces. Couldn’t help thinking there was a bit more life somewhere else.”

The East Coast can be hostile in different ways. David thrived at Amherst; but not at Harvard. I talked to David long after he’d abandoned Harvard and gone on to Illinois normalcy and extraordinary literary achievement. I met him when he tried to interest me in publishing a book on Cantor’s philosophy of mathematics. David was not goofinig around with philosophy. David was raised in the richest philosophical soil we have in this country, the equivalent of the black earth of Illinois where he lived so long. We Americans are good at this stuff, and have been since the time of Perice and Royce. I know his uncle, John Wallace, a philosopher at Minnesota with whom I worked closely when I worked at the University of Minnesota Press; and I knew of his father, a philosopher of highest repute at Illinois. This book on Cantor was not a fit for my list which features really technical books like those of Willard van Orman Quine, but the manuscript was really good. When we talked about why he left philosophy, he mentioned a snot-nosed grandee at Harvard who was unpleasant and treated him and not just him with disdain. I was sorry he did not find the really loving folks our department has, but that’s the way it was. And I would have been and had been just as put off by that guy’s behavior.

I was going to write that philosophy’s loss was literature’s gain, but that is glib and false. He never stopped being the sharpest of thinkers, and what I love about books like Supposedly Fun Thing is that the reasoning is so powerful and all set forth in a pop style that makes it a delight to for me to read .

So he left the provinces for LA. It’s a city that’s been hard on lots of writers.

David was a half-generation younger than me, but I’m taking his loss personally. He bridges the generations: my son Eric loves his writing as much as I do. We once went to hear him read from a new book, ironically in Emerson Hall at Harvard where the philosophy department has its offices. For me seeing him go is like seeing one of the most hopeful signs of life in this country gone. All the more reason, I feel, for me to pursue what I understand as his agenda for thinking—opening up the doors of perception.

Katharine Weber:

David Foster Wallace forever changed the way I regard footnotes. Because of his brilliance and originality, whenever I am reading a text with footnotes I turn to them eagerly, armed with the expectation that the universe just might expand a little more in a surprising way, hoping that the tiny print will fizz like Pop Rocks with witty precision. I am almost always disappointed. But I will read the next one, and the next one, hoping to find that graceful, magical elucidation one more time.

Antoine Wilson:

I didn’t know DFW personally, but reading his words, I often imagined I did. The Metafilter thread alone demonstrates that I’m not alone in this, not by a long shot. In that sense, at least, DFW was successful in his aim to counter our everyday sense of alienation. It’s a deep shame that he couldn’t likewise benefit from his own gift.

James Wood:

I was terribly saddened to hear this news. Whatever one felt about his work, it was hard to imagine any serious reader of fiction not being intensely interested in what he was going to do next. I had been looking forward to witnessing his literary journey, and to adjusting my own opinions and prejudices — or rather, being forced by the quality of the work to do so. Of great interest to me was his own ambivalent relation with some elements of postmodernism (irony, too-easy elf-consciousness, and so on), and the burgeoning presence of moral critique in his work. One had the feeling that his new work was being written under considerable pressure — and I don’t just mean psychological pressure, but the pressure of staying loyal to his fractured, non-linear epistemology while at the same time incorporating some of that admiration he had for the concerns of the nineteenth-century novel. To put it flippantly, he was aesthetically radical and metaphysically conservative, and the negotiation of that asymmetry would have been a marvelous thing to follow, as a reader.

An untruthful reviewer of my book, How Fiction Works, claimed that David Foster Wallace was its “aesthetic villain.” That is not true. I discussed him as an extreme example of a tension I think is endemic to post-Flaubertian fiction, which is the question, as Martin Amis once put it, of “who’s in charge”: is it the stylish author, who sees the world in his fabulous language, or his probably less stylish characters, who are borrowing the author’s words? Wallace’s fiction, I wrote, “prosecutes an intense argument about the decomposition of language in America, and he is not afraid to to decompose — and discompose — his own style in the interests of making us live through this linguistic America with him.” One of the most impressive aspects of Wallace was that stylistic fearlessness.

On Friday, I was pondering writing a note to Wallace to say as much (and to correct the impression he might have got from that review), and then on Saturday came the terrible news — “like a man slapped.”

Leigh: But as to the jewelry as a symbol of cyclical anything, I don’t know whether I’d go along with that one.

Leigh: But as to the jewelry as a symbol of cyclical anything, I don’t know whether I’d go along with that one.

Now how can Joan Chen compete with that? Well, she can’t. But then the film’s more fabricated “characters” tend to have more problematic ironies going on. We’re expected to believe that the still quite attractive Chen is having difficulties finding a man. Her character tells us she’s happy being single while she cries. And her character, Little Flower, was named so because she resembled Joan Chen in the 1979 film of the same name. There is also Tao Zhao as Su Na, born in 1982 and employed as a professional shopper for the rich. Her goal is to acquire as much money as possible so that her parents might live in one of the luxury apartments being erected where the former factory was. Her credentials? She is the “daughter of a worker.” But she’s not just a daughter. She plays one on TV.

Now how can Joan Chen compete with that? Well, she can’t. But then the film’s more fabricated “characters” tend to have more problematic ironies going on. We’re expected to believe that the still quite attractive Chen is having difficulties finding a man. Her character tells us she’s happy being single while she cries. And her character, Little Flower, was named so because she resembled Joan Chen in the 1979 film of the same name. There is also Tao Zhao as Su Na, born in 1982 and employed as a professional shopper for the rich. Her goal is to acquire as much money as possible so that her parents might live in one of the luxury apartments being erected where the former factory was. Her credentials? She is the “daughter of a worker.” But she’s not just a daughter. She plays one on TV.

Wood offered some resistance to blogs, but confined his gripes to comments. “There, I think the rule is sanctioned ignorance,” said Wood. And while he outlined a generalized pattern of how people react to a review that I felt fallacious, the difference between Wood and Mendelsohn is that the former was willing to give the format a chance and try to understand it, while the latter was happy to nuke the site from orbit like an uninformed cretin.

Wood offered some resistance to blogs, but confined his gripes to comments. “There, I think the rule is sanctioned ignorance,” said Wood. And while he outlined a generalized pattern of how people react to a review that I felt fallacious, the difference between Wood and Mendelsohn is that the former was willing to give the format a chance and try to understand it, while the latter was happy to nuke the site from orbit like an uninformed cretin.

In 1997, I was given a book. A big book. A book backloaded with endnotes. It had been given to my sister

In 1997, I was given a book. A big book. A book backloaded with endnotes. It had been given to my sister