Alexis Madrigal: “Brooklyn College sociologist Alex Vitale, who has specialized in tracking police tactical changes, found that the the ‘broken windows’ theory of policing, which was introduced to a national audience by this very magazine, has also had a major impact on protest policing. As we wrote in 1982, broken windows policing did not attempt to directly fight violent crime but rather the ‘sense that the street is disorderly, a source of distasteful, worrisome encounters.’ As Vitale would put it, the theory ‘created a kind of moral imperative for the police to restore middle class values to the city’s public spaces.’ When applied to protesters, the strategy has meant that any break with the NYPD’s behavioral preferences could be grounds for swift arrest and/or physical violence.”

In the December 2011 issue of Philadelphia Magazine, there was a list printed on Page 72 with the heading which read THINGS WE NEED TO GET RID OF. Among the items listed? The Mummers. Poet CA Conrad went onto Philadelphia Magazine‘s Facebook page and demanded that it write a letter of apology. There was no response. He kept writing. He was blocked from the site. So Conrad went to the magazine’s office in person. He was polite. He did not yell. He asked to speak with the online editor. He was told no one was in. Nobody had the courage to talk with him. Instead, the Philadelphia Magazine receptionist called the police. “The truth is that they were embarrassed by what I was saying,” wrote Canto on his blog. “And they gloated over my removal from the office on Face Book. Oh, and while I was being escorted OUT, one of the magazine’s enforcers said that I was to be arrested if I ever stepped foot inside the building again. NICE!” (I learned of this story from HTML Giant.)

“Behavioral preferences.” That’s not unlike the highly elastic term “juvenile delinquency.”

A parent in Calvert County, Maryland wrote into The Bay Net. Her six-year-old daughter Brianna had made an “inappropriate comment” at Dowell Elementary, saying she was going to kill another student. This was a joke. She was pulled from recess by a teacher and ordered to sit and wait in various administrative rooms. Brianna assured the principal that she was only joking and that she had no intent of killing her fellow students. Despite her confession, the principal then grilled Brianna about her home life. Other students were brought in. One of Brianna’s good friends was pressured to rat her out — this, after she had already confessed as to the nature of her comment. The parent asked in her letter, “How do you justify not calling the parent of a six year old and holding her in the office for 2 hrs asking her about her life at home over an innocent comment? Do not get me wrong, I know what she said was inappropriate but to all that know my daughter know that she would never intentionally hurt anyone!! How do you justify treating her this way? This is the problem, noone will or can justify this to me. I email jack smith the super of cc schools, I of course get pushed onto someone else who calls me asks me what happens and about the only response I get it ‘well as ling as you do understand what she did was wrong!’ Really? I have yet to speak to the super as I’m told he is very busy with meetings….!”

The Guardian: “James Harding, speaking at the Society of Editors conference on Monday, was talking days after Tom Watson accused James Murdoch in parliament of being the ‘first mafia boss in history who didn’t know he was running a criminal enterprise.’ A clearly irritated Murdoch responded that he thought this was an ‘inappropriate’ comment.”

Etymology for irritated: 1530s, “stimulate to action, rouse, incite,” from L. irritatus, pp. of irritare “excite, provoke.” An earlier verb form was irrite (mid-15c.), from O.Fr. irriter. Meaning “annoy, make impatient” is from 1590s.

It took only six decades for “irritate” to have its meaning corrupted.

At a Cannes press conference on May 18, 2011, the filmmaker Lars von Trier stated, “I understand Hitler but I think he did some wrong things yes absolutely but I can see him sitting in his bunker.” These words were received with understandable umbrage. Von Trier apologized the next day, purporting that his remarks were meant in jest. “I am not anti-Semitic or racially prejudiced in any way, nor am I a Nazi.” Despite this apology, he was banned from the Cannes Film Festival, declared persona non grata with the decision supported by French culture minister Frederic Mitterand. Mitterand remarked of the ban, “There is a major difference between a film that was chosen in a calm atmosphere and a director who clearly blew a fuse.” Yet in 2009, Mitterand protested Roman Polanski’s September 26 arrest in Amsterdam, “To see him thrown to the lions and put in prison because of ancient history — and as he was traveling to an event honoring him — is absolutely horrifying.” Why are terrible words uttered in 2011 more “horrifying” than terrible action in 1977? It took a day for Lars von Trier to apologize and nearly 35 years for Polanski to apologize.

In January 2011, the BBC apologized for remarks made by Stephen Fry on the comedy quiz show, QI Fry had made a quip about Tsutomu Yamaguchi, a man who had survived both the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Fry called Yamaguchi “the unluckiest man in the world.” Japanese viewers, watching the clip on YouTube, became irate and wrote in. Japanese blogger Yuko Kato wrote: “So, in this sad case, literally a comedy of errors, the lack of knowing and understanding goes both ways. The BBC and the people involved in the QI segment (including Stephen Fry, whom I dearly love) failed to anticipate Japanese sensitivities; and if they had but still went on with the broadcast then that’s even worse. For as a Japanese (despite my unabashed love of British comedy), I was very uncomfortable with the segment, especially with the audience tittering. On the other hand (no limbs left), most of the Japanese public have absolutely no idea what British humour is about; they simply don’t know that it’s a form of expression that strives to tell things like it is, that it’s an art form that tries to illuminate all the foolishness and idiosyncracies and negativities of the world through irony.”

In February, fashion designer Kenneth Cole tweeted, “Millions are in uproar in #Cairo. Rumor is they heard our new spring collection is now available online.” Outrage ensued.

DJ Gardner was ranked the 64th best college basketball player in the country. He was a freshman forward standing six-foot-seven, an accomplished shooter described by a former high school coach as “an unselfish kid” who understood that it didn’t matter which player made the points. He was wooed by Mississippi State, told by the smiling men that he’d get serious time on the court and, like any hardworking kid baffled by the two other young men rotating as shooting guard, agreed to a redshirt year for the freshman season. On Twitter, he let off some steam:

These bitches tried to fuck me over.. That’s y I red shirted .. But I wish my homies a great ass season.. I don’t even know y I’m still here

He called the top brass “liars.” Mississippi State coach Rick Stansbury booted Gardner off the team for his tweeting, claiming his words to be “repeated action detrimental to the team.” And while Gardner’s mother, Angela, was hardly happy with the behavior of her son and the coach, she said, “I felt like there should’ve been some communication.”

On July 3, 2011, Charles Hill was shot by BART police in the Civic Center station in San Francisco. Hill was drunk. He pulled a knife and threw it at the floor. And the police shot and killed Hill. Witnesses reported that Hill had neither ran nor lunged at the two cops. The police claimed Hill was using an open liquor bottle as a weapon. BART police chief Kenton Rainey claimed he was “comfortable” with the decision of his men.

This brutal incident led many to exercise their First Amendment rights to protest Hill’s death. But on August 11, 2011, BART muzzled cell phone service at four stations, ridding the protesters of their right to coordinate a peaceful assembly. The ACLU of Northern California replied:

All over the world people are using mobile devices to organize protests against repressive regimes, and we rightly criticize governments that respond by shutting down cell service, saying it’s anti democratic and a violation of the right to free expression and assembly. Are we really willing to tolerate the same silencing of protest here in the United States?

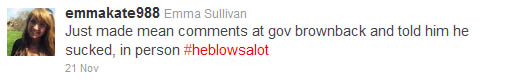

On November 21, 2011, a Kansas high school student named Emma Sullivan attended a Youth in Government program, listening to a speech by Governor Sam Brownback and ridiculing him on Twitter under the hashtag “#heblowsalot.” Brownback’s office spotted Sullivan’s tweet during “routine media monitoring” and forced Sullivan’s principal to ask Sullivan to write an apology letter. Sullivan refused, but she did say, “I think it would be interesting to have a dialogue with him. I don’t know if he would do it or not though. And I don’t know that he would listen to what I have to say.” Sullivan’s mother said that she wasn’t angry with her daughter. The story made the rounds. Brownback issued an apology.

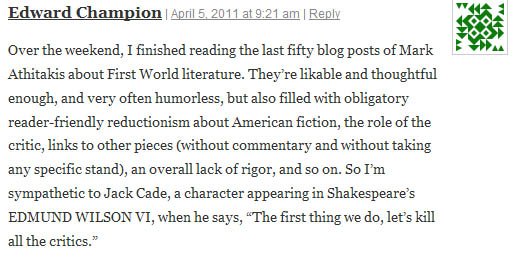

On the afternoon of July 19, 2011, I was contacted by a detective from the Cheverly Police Department. The detective was a nice and reasonable guy. He explained to me that blogger and critic Mark Athitakis was accusing me of harassment. What was so harassing? Several comments — all under my real name, really a bunch of silly performance art that I had been leaving intermittently over the last few months, nothing intended to harm and more than a bit absurdist — one evoking a fictitious Shakespeare quote reading “let’s kill the critics” and the like. I told the detective that these comments were clearly satirical. That a comment containing the lyrics for Rebecca Black’s “Friday” could not possibly be written with violence or threats in mind. The detective agreed that he and I both had better things to do with his time. He was merely checking up on the complaint that he received.

At no time did Mark ever contact me personally to (a) clarify the beef that he has with me, (b) state that I was harassing him. He did email me on July 14th, writing, “Your behavior is abusive, disrespectful, and unacceptable. It has to stop.” I emailed him a suggestion on how to clear things up, writing, “If you want to use this email as an opportunity, then I’m all ears.” He repeated the same line in another email on July 15th. I replied, “This comment is not abusive. Here are the facts: you have no sense of humor, you are disrespectful of my thoughts and voice, and you cannot take criticism.”

That was the last direct contact I had with Athitakis. I did not visit his site again until July 19, 2011, when I was attempting to explain the situation to the detective. So Athitakis must have filed the complaint with the Cheverly Police Department after this exchange.

On October 2, 2011, then New York Times freelance journalist Natasha Lennard was arrested on the Brooklyn Bridge while covering the Occupy Wall Street protests. On October 14, 2011, she spoke before a panel at Blue Stockings, expressing her opinions about organizing protests and using colorful language. A right-wing website, unable to see the distinction between reporting and opinion, posted the video with speculation, demanding “appropriate disciplinary action against Lennard” and asking her to rat out “any potential planned criminal activity by Occupy activists.”

Natasha Lennard responded with a Salon essay, “Why I quit the mainstream media”:

As the Times publicly noted, they found no problem with any of the reporting I had done for them on OWS. Indeed, a court hearing upheld that I had been on the Brooklyn Bridge as a professional journalist and as such, deserved to have the disorderly conduct charge against me dismissed. The only reason I was on the Brooklyn Bridge that day was as a reporter, gathering and relaying information on what I saw, and nothing else. However, as has become clear, if I — or any other journalist — want to express a strong opinion on a political matter, I cannot contemporaneously report for a mainstream publication.

From a New York Times opinion piece written by Rebecca MacKinnon (November 15, 2011):

Adding to the threat to free speech, recent academic research on global Internet censorship has found that in countries where heavy legal liability is imposed on companies, employees tasked with day-to-day censorship jobs have a strong incentive to play it safe and over-censor — even in the case of content whose legality might stand a good chance of holding up in a court of law. Why invite legal hassle when you can just hit “delete”?

The potential for abuse of power through digital networks — upon which we as citizens now depend for nearly everything, including our politics — is one of the most insidious threats to democracy in the Internet age. We live in a time of tremendous political polarization. Public trust in both government and corporations is low, and deservedly so. This is no time for politicians and industry lobbyists in Washington to be devising new Internet censorship mechanisms, adding new opportunities for abuse of corporate and government power over online speech.

And let us not forget this horseshit…

http://www.theatlanticwire.com/global/2011/12/american-will-go-jail-insulting-thai-king/45924/