(This is the second entry in the The Modern Library Reading Challenge, an ambitious project to read the entire Modern Library from #100 to #1. Previous entry: The Magnificent Ambersons)

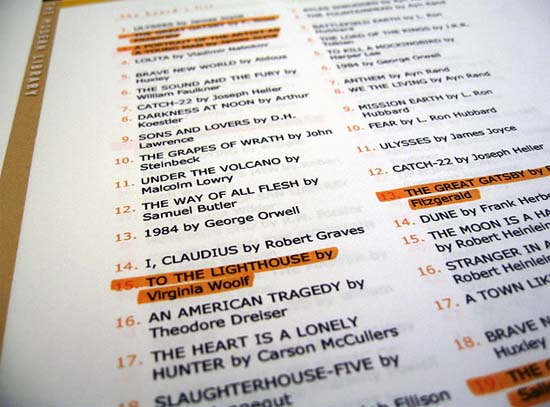

I feel morally obliged to point out that I am hardly the only person attempting to read all of the Modern Library titles. When I first considered this project, I was completely unaware of Lydia Kiesling’s Modern Library Revue — despite being a fairly regular reader of The Millions (and trivial contributor). I was also pleasantly surprised to discover a blog called The Modern Library List of Books run by a mysterious Canadian woman named Devon S., who now lives in New York City (after a stint in Paris). Devon is also reading the Modern Library from #100 to #1, and is now at #87 after a little more than a year. I’d also be remiss to dismiss Rachael Reads. Rachael, like Lydia, is reading the Modern Library titles out of order. I smiled a long while over the Connecticut Museum Quest’s slower but very noble efforts to read three Modern Library books a year — which, by my math, works out to about 40 years for the 121 books. This seems to me a very sensible long-term commitment. Still, if you can’t read them all, you can always just take on the authors more reflective of 21st century enlightenment.

I feel morally obliged to point out that I am hardly the only person attempting to read all of the Modern Library titles. When I first considered this project, I was completely unaware of Lydia Kiesling’s Modern Library Revue — despite being a fairly regular reader of The Millions (and trivial contributor). I was also pleasantly surprised to discover a blog called The Modern Library List of Books run by a mysterious Canadian woman named Devon S., who now lives in New York City (after a stint in Paris). Devon is also reading the Modern Library from #100 to #1, and is now at #87 after a little more than a year. I’d also be remiss to dismiss Rachael Reads. Rachael, like Lydia, is reading the Modern Library titles out of order. I smiled a long while over the Connecticut Museum Quest’s slower but very noble efforts to read three Modern Library books a year — which, by my math, works out to about 40 years for the 121 books. This seems to me a very sensible long-term commitment. Still, if you can’t read them all, you can always just take on the authors more reflective of 21st century enlightenment.

The Modern Library list has only been around for thirteen years. Yet already people are happy to share their reading adventures and their unanticipated epiphanies. Evelyn Waugh becomes a “bi-curious hipster boyfriend.” (I hope to respond to that intriguing proposition when I eventually hit #80, assuming hipsters — and Michael Cera’s career — still exist by the time I get to Brideshead.) Midnight’s Children reminds another of “the many Englishes in the world.”

For my own part, Sebastian Dangerfield, the wonderfully monstrous protagonist of J.P. Donleavy’s The Ginger Man, recalled Johnny (Donleavy’s first name) in Mike Leigh’s Naked. In fact, in Leigh’s film, the sadistic landlord Jeremy G. Smart identifies himself as “Sebastian Hawk.” Apparently, I wasn’t alone in making this association. An interviewer named Gineen Cooper, writing for a literary magazine called The Pannus Index, even asked Donleavy if he had seen Leigh’s movie. (Donleavy hadn’t.) I don’t know if I buy Ms. Cooper’s theory of the “anarchic Dionysian rhetoric which underlines both characters’ personalities” — in part because ideology is the wrong method with which to consider both Johnny and Dangerfield. Also, in Dangerfield’s case, we are dealing with a character bifurcated on the page. (More on this in a bit.) For both characters, surely the behavior here is fascinating enough. But when Donleavy’s Sebastian said to his mate, “I’m twenty-seven years old and I feel like I’m sixty,” I couldn’t help thinking of Mike Leigh’s Johnny being misidentified as forty while stating his age as twenty-seven.

Irrespective of these parallels, The Ginger Man turned out to be a grand hoot — very aggressive and funny, certainly more interesting and stylistically daring than The Magnificent Ambersons in its exploration of youthful hubris. (And what is it with the Modern Library books and prickish protagonists so far? I certainly hope that the behavioral spectrum expands in the next several books!) The Ginger Man is the kind of novel you give to a finger-shaking dogmatist who insists that some modest behavioral infraction on your part, talked out through apologia and attentive listening, instantly transforms you into an asshole. Sebastian Dangerfield, like Humbert Humbert, is one of the great assholes of 20th century literature: he is charismatic, he somehow talks women into bed (but not all of them), he is tolerated by many despite his boorishness, and he is more than a bit sociopathic. Dangerfield carries the redolent stench of entitlement. Here is a young man purportedly studying law at Trinity College, one who has great responsibilities to his wife Marion and his kid. Yet he thinks nothing of plundering the last stash of cash and blowing it all on stout, much less taking up an affair with the very woman who sublets the room. And if that isn’t degenerate enough for you, Dangerfield leeches off his friends, even after his friends have become paupers:

I have discovered one of the great ailments of Ireland, 67% of the population have never been completely naked in their lives. Now don’t you, as a man of broad classical experience, find this a little strange and perhaps even a bit unhygienic. I think it is certainly both of those things. I am bound to say that this must cause a good deal of the passive agony one sees in the streets. There are other things wrong with this country but I must leave them wait for they are just developing in my mind.

That’s a portion from Dangerfield’s letter in response to his friend Kenneth O’Keefe, who has written to Dangerfield a few chapters earlier of his dire straits in France. O’Keefe is hungry “enough to eat dog,” rationing himself twelve peas for every meal, claiming impotence, and, most importantly, counting upon the money that Dangerfield promised he would pay him back. But Dangerfield would rather offer a foolish philosophy than own up to his responsibilities as both friend and debtor.

His truly unpardonable behavior even gets him into the newspapers (“His eyes were given as very wild,” reports the broadsheet, suggesting a descriptive shortsightedness from the witnesses, the reporter, the police, all of Ireland herself!), and yet this Ginger Man is strangely capable of getting away with much — defying the Irish Guard, flouting the drinking curfews, terrifying bartenders and train passengers, and even stringing naive young girls along and persuading them to spend their hard-earned cash on him.

Donleavy is quite clever in the way he invites the reader to figure out why Dangerfield is so loutish. Dangerfield never quite tells us what he wants. (In the letter I quoted above, we see the way that Dangerfield tries comparing his troubles to those of Ireland. First-class narcissism. But even this still doesn’t entirely answer the question of why he behaves this way.) When Dangerfield talks with a sketchy man named Percy Clocklan, Dangerfield asks him, “What would you like out of life, Percy?” Is the aimless Dangerfield merely passing the time? Is he tolerated because of this apparent flattery?

On the other hand, the book is working from a highly stylized interior monologue. Donleavy swaps between first-person and third-person — often in the same paragraph and very frequently in clipped sentences (the latter is almost a neutral mediator, a voice somewhere between Dangerfield and narrator):

Sebastian crawled naked through the morning room into the kitchen. Turned the key and scrabbling back to the morning room, waiting under the table. Through the mirror on the opposite wall he saw he saw the cap of the mailman pass by. I’ve got to see the postman. Get a blanket off Mrs. Frost’s bed.

That passage comes later in the book, when Dangerfield’s house (rented from a landlord named Egbert Skully) has fallen into slovenly disrepair and funds aren’t coming anytime soon. Which means, of course, that Dangerfield is on the run. His strategy is to carry on being a shit. The mirror imagery, omitting the reflection of our narcissistic hero, may suggest that one of Dangerfield’s main problems is a profound inability to see what he does. This self-delusion is further suggested by the way in which Dangerfield’s first-person interventions begins to take up a greater portion of the story as both the book (and Dangerfield’s life) carries on.

Yet for long stretches of the book, this ignoble beast evades nearly every punitive fate. How does a guy like Dangerfield get away with this crassitude? Another clue be found in Donleavy’s excellent dialogue (it’s hardly an accident that Donleavy had the chops to adapt this novel into a play), suggesting that our hero’s primary skill is the right combination of witty quips and backhanded compliments:

“My dear Chris, you do have a lovely pair of legs. Strong. You hide them.”

“My dear Sebastian, I do thank you. I’m not hiding them. Does that make men follow one?”

“It’s the hair that does that.”

“Not the legs?”

“The hair and the eyes.”

Dangerfield does get some form of comeuppance near the end (he lives for his inheritance, but he learns that his inheritance has been planned around the way he lives), yet within the safety of the novel, this titular Ginger Man, running from Dublin to London, can’t be caught. “You’re a terrible man, Sebastian,” says one character late in the novel. “Merry fraud,” replies Dangerfield, in a bit of wordplay directed to two serious victims (Marion, his wife; Mary, a girl he runs off with).

It’s worth pointing out that this was pretty hot stuff back in 1955, skirting the line between literary comedy and perceived obscenity. After The Ginger Man was rejected by nearly every major publisher, Maurice Girodias of The Olympia Press agreed to publish it. Unfortunately for Donleavy, Girodias published The Ginger Man as part of its Traveller’s Companion Series, listing it as a “special volume” with such titles as Richardson’s The Sexual Life of Robinson Crusoe, Lengel’s White Thighs, Van Heller’s Rape, and Jones’s The Enormous Bed. The Ginger Man was published as pornography. This may seem tame in 2011, but in the mid-20th century, writers, often going by pen names, could be blacklisted or even arrested for such associations. It didn’t help that Girodias had expressly violated the terms that he and Donleavy had agreed to. As The Ginger Man garnered global renown, there were years of litigation and disputes over the rights. Eventually Girodias went bankrupt, giving Donleavy a chance to buy up the Olympia Press rights He found himself in a courtroom suing himself.

Donleavy, it turns out, is still alive. Last August, the Independent tracked him down — under the proviso that the newspaper would host a picnic and provide all the food and drink. He didn’t say much. In The History of The Ginger Man, Donleavy wrote about what his friend, the bestselling (and now largely forgotten) novelist Ernest Gebler, told him about what authors do when they get rich:

“Mike, they buy binoculars, shotguns, sports cars and fishing rods, and a big estate to use them on. And then outfitted in their new life, along with new bathrooms, wallpaper and brands of soap, they make a fatal mistake and change their women. To schemingly get toasted and roasted on glowing hot emotional coals, and subjected to a whole new set of tricks and treacheries. Which leaves that author spiritually disillusioned and minus his favorite household implements.”

Donleavy, who has seen 45 million copies of The Ginger Man sold (the book has never gone out of print), still lives cheaply despite his success. He seems to have followed Gebler’s advice.

Different people have different approaches. One would think that McGonigal, having a PhD, would understand this basic truism. But then McGonigal,

Different people have different approaches. One would think that McGonigal, having a PhD, would understand this basic truism. But then McGonigal,  McGonigal uses the word “addictive” as a positive modifier. “What makes Tetris so addictive,” McGonigal writes, “is the intensity of the feedback it provides.” Wait a minute. Isn’t intensity a problem if we’re trying to contend with a mad influx of feedback? Later in the book: “By providing a goal-oriented, feedback-rich, obstacle-intensive environment for dancing, [Top Secret Dance Off, McGonigal’s project] makes dancing more motivating, fun, and addictive.” There’s a variation of “intense” and “feedback” again. Still, no clear answers on the “addictive” question. And isn’t it a bit self-serving and highly disingenuous to write in general marketing terms about your own game project? “Of course, we’ve also developed many external shortcuts to triggering our hardwired happiness systems: addictive drugs and alcohol….But none of these methods are sustainable or effective in the long term.” Wait a minute! If you’re applying “addictive” to something that isn’t sustainable, then is it safe to say that video games might prove just as unsustainable or ineffectual in the long term?

McGonigal uses the word “addictive” as a positive modifier. “What makes Tetris so addictive,” McGonigal writes, “is the intensity of the feedback it provides.” Wait a minute. Isn’t intensity a problem if we’re trying to contend with a mad influx of feedback? Later in the book: “By providing a goal-oriented, feedback-rich, obstacle-intensive environment for dancing, [Top Secret Dance Off, McGonigal’s project] makes dancing more motivating, fun, and addictive.” There’s a variation of “intense” and “feedback” again. Still, no clear answers on the “addictive” question. And isn’t it a bit self-serving and highly disingenuous to write in general marketing terms about your own game project? “Of course, we’ve also developed many external shortcuts to triggering our hardwired happiness systems: addictive drugs and alcohol….But none of these methods are sustainable or effective in the long term.” Wait a minute! If you’re applying “addictive” to something that isn’t sustainable, then is it safe to say that video games might prove just as unsustainable or ineffectual in the long term?  “What the world needs now are more epic wins,” writes McGonigal in typical Pollyanna mode, “opportunities for ordinary people to do extraordinary things — like change or save someone’s life — every day.” By nearly every philosophical standard, this statement is laughable. A Grand Theft Auto IV player may very well find pride in biking up the highest virtual mountain from the city (as McGonigal cites). While this alleviates boredom and occupies time, is this really comparable with saving a person’s life? McGonigal brings up Joe Edelman’s Groundcrew, which McGonigal describes as “a wish panel for real people.” But in an interview with McGonigal, Edelman reveals that this represents little more than entitlement and narcissistic wish fulfillment:

“What the world needs now are more epic wins,” writes McGonigal in typical Pollyanna mode, “opportunities for ordinary people to do extraordinary things — like change or save someone’s life — every day.” By nearly every philosophical standard, this statement is laughable. A Grand Theft Auto IV player may very well find pride in biking up the highest virtual mountain from the city (as McGonigal cites). While this alleviates boredom and occupies time, is this really comparable with saving a person’s life? McGonigal brings up Joe Edelman’s Groundcrew, which McGonigal describes as “a wish panel for real people.” But in an interview with McGonigal, Edelman reveals that this represents little more than entitlement and narcissistic wish fulfillment:  “Epic” is another modifier that McGonigal likes a great deal. She’s fond of bringing up meaningless achievements, such as the fact that, on April 2009, Halo 3 players scored 10 billion kills against the Covenant. “Ten billion kills wasn’t an incidental achievement, stumbled onto blindly by the gaming masses,” writes McGonigal. “Halo players made a concerted effort to get there.” You may as well jump up and down over the 30,000 Americans who killed themselves last year. Weren’t their suicides also “a concerted effort to get there?” Should we celebrate the fact that several trillion cigarette butts litter the streets worldwide every year? Simply the pollution is worthwhile because of its “epic” results. Bigger doesn’t necessarily mean better. And on the subject of Halo, McGonigal also praises the Halo Museum of Humanity — a startlingly convincing shrine that provides “epic context for heroic action.” What McGonigal calls “epic context,” I call “slick marketing.” And I’ll even go further.

“Epic” is another modifier that McGonigal likes a great deal. She’s fond of bringing up meaningless achievements, such as the fact that, on April 2009, Halo 3 players scored 10 billion kills against the Covenant. “Ten billion kills wasn’t an incidental achievement, stumbled onto blindly by the gaming masses,” writes McGonigal. “Halo players made a concerted effort to get there.” You may as well jump up and down over the 30,000 Americans who killed themselves last year. Weren’t their suicides also “a concerted effort to get there?” Should we celebrate the fact that several trillion cigarette butts litter the streets worldwide every year? Simply the pollution is worthwhile because of its “epic” results. Bigger doesn’t necessarily mean better. And on the subject of Halo, McGonigal also praises the Halo Museum of Humanity — a startlingly convincing shrine that provides “epic context for heroic action.” What McGonigal calls “epic context,” I call “slick marketing.” And I’ll even go further.  Aside from the fact that one doesn’t need a video game to create this type of needlessly limited community (why should people “interact”around a singular interest?), this is a troubling Kinsey-like approach to socialization. As anyone who has ever attended a science fiction convention knows, a common interest doesn’t necessarily ensure a lasting social bond. But don’t tell that to McGonigal, who confuses this grouping with communitas, “a powerful sense of togetherness, solidarity, and social connection. And it protects against loneliness and alienation.” Let’s see how well communitas worked out during the Blessed Sacrament procession, courtesy of Michael J. Sallnow’s Contesting the Sacred:

Aside from the fact that one doesn’t need a video game to create this type of needlessly limited community (why should people “interact”around a singular interest?), this is a troubling Kinsey-like approach to socialization. As anyone who has ever attended a science fiction convention knows, a common interest doesn’t necessarily ensure a lasting social bond. But don’t tell that to McGonigal, who confuses this grouping with communitas, “a powerful sense of togetherness, solidarity, and social connection. And it protects against loneliness and alienation.” Let’s see how well communitas worked out during the Blessed Sacrament procession, courtesy of Michael J. Sallnow’s Contesting the Sacred:

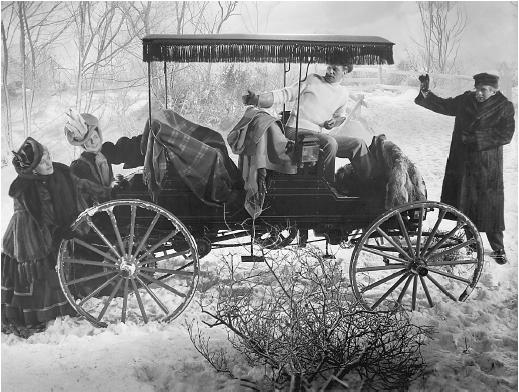

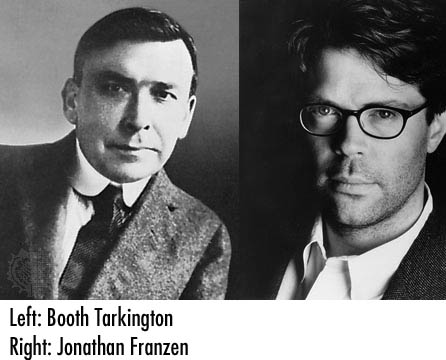

By all reports, Booth Tarkington was hot shit sometime in the early 20th century. It is quite possible that he was the kind of man who entered a room and announced with his very presence: “Do you know who I am?” How do we know this? Well, he won the Pulitzer Prize twice (for Ambersons and Alice Adams). He had family members who were politicians (his uncle, Newton Booth, was the eleventh Governor of California and a United States Senator) and Tarkington himself was elected to the Indiana State Legislature.

By all reports, Booth Tarkington was hot shit sometime in the early 20th century. It is quite possible that he was the kind of man who entered a room and announced with his very presence: “Do you know who I am?” How do we know this? Well, he won the Pulitzer Prize twice (for Ambersons and Alice Adams). He had family members who were politicians (his uncle, Newton Booth, was the eleventh Governor of California and a United States Senator) and Tarkington himself was elected to the Indiana State Legislature.  Yet since we are forced to contend with both Tarkington’s racism and his natural gifts as a novelist, perhaps we have a truer sense of 1918’s ideological incoherence than the weak-kneed politically correct type hoping to scrub out the ugliness. Books like The Magnificent Ambersons are uncomfortable and test the disposition. Would Jonathan Franzen have ended up like this, if he had been born ninety years earlier? Would Franzen (bigshot social novelist of his time) have hated black people as much as Tarkington (bigshot social novelist of his time) did? Perhaps. Perhaps Faulkner’s maxim applies: a writer is congenitally unable to tell the truth and that is why we call what he writes fiction.

Yet since we are forced to contend with both Tarkington’s racism and his natural gifts as a novelist, perhaps we have a truer sense of 1918’s ideological incoherence than the weak-kneed politically correct type hoping to scrub out the ugliness. Books like The Magnificent Ambersons are uncomfortable and test the disposition. Would Jonathan Franzen have ended up like this, if he had been born ninety years earlier? Would Franzen (bigshot social novelist of his time) have hated black people as much as Tarkington (bigshot social novelist of his time) did? Perhaps. Perhaps Faulkner’s maxim applies: a writer is congenitally unable to tell the truth and that is why we call what he writes fiction.

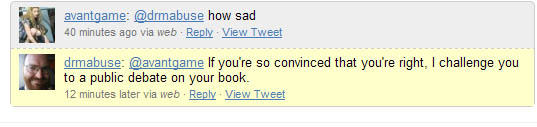

There comes a time when you need to raise the stakes.

There comes a time when you need to raise the stakes.