Dave Eggers is running away from the truth. And we have the video to prove it.

In 2009, Dave Eggers self-published Zeitoun, a well-received nonfiction volume which told the story of a hard-working Syrian-American painter in New Orleans who emerged as a hero during Hurricane Katrina. Eggers relied heavily on what his subjects, Abdulrahman Zeitoun and his wife Kathy, told him while working on the book. As he claimed in a Rumpus interview, “I think you get the most accuracy when you involve your subjects as much as possible. I think I sent the manuscript to the Zeitouns for six or seven reads. They caught little inaccuracies each time.”

Recent developments have revealed that Zeitoun is a misleading feel-good hagiography running against this apparent commitment to accuracy. The New York Times Book Review‘s Timothy Egan suggested that Eggers was a modern-day “Charles Dickens, his sentimentality in check but his journalistic eyes wide open.” But Eggers has glossed over a good deal more than what Egan has insinuated. Abdulrahman Zeitoun is not the calm and peaceful man that Eggers portrayed.

On November 8th, Zeitoun was indicted for attempted first-degree murder and solicitation of first-degree murder. Kathy had suffered abuse from the beginning of her marriage to Abdulrahman. In court, Kathy testified about being beaten with a tire iron and being “[choked] so hard I felt the pressure in my face.”

Last August, when we reported on the Zeitoun Foundation’s questionable finances, we discovered that at least $161,331 (during the year 2009) was siphoned off to a shadowy organization named Jableh, LLC. We reached out to various representatives from McSweeney’s by telephone and email, but they refused to speak with us. (We did, however, receive a threatening email from an attorney. We responded by asking the attorney to provide us with specific evidence that would clear up matters. He did not return our email.) Throughout these developments, Eggers has remained silent, save for a statement that appeared on the Zeitoun Foundation’s website which has since been deleted.

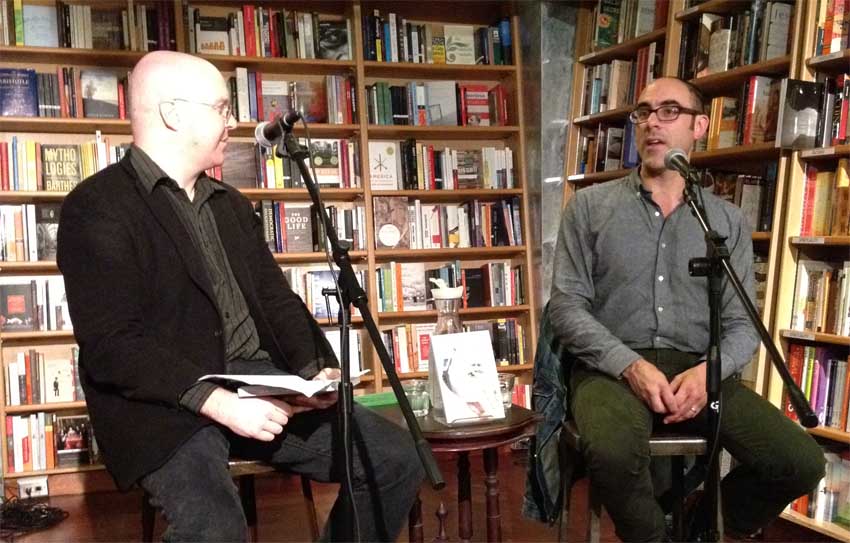

On Wednesday night, we decided to question Dave Eggers at the National Book Awards in person, where he was being feted as a finalist for his latest novel, A Hologram for the King, hoping that Eggers would break his silence and provide us with a clear-eyed statement on these serious mistakes and moral indiscretions.

But Eggers ran away at the name of “Abdulrahman Zeitoun.” The video can be seen below:

Eggers’s silence (along with that of mainstream literary outlets) is baffling. Even Norman Mailer famously declared during the Jack Abbott affair that culture is worth a little risk. If Eggers is interested in culture, should he not come to terms with his mistakes? Should he not own up to the negative impact that his book and his involvement may have had on the Zeitouns’ lives?

John Simerman’s helpful dispatches in the New Orleans Times-Picayune illustrate why staying silent or taking the rose-tinted path is a blatant and irresponsible disregard for the truth. On October 18th, Kathy Zeitoun testified in court about the abuses:

He starts beating me in the back with this tire iron. He lets go of the tire iron and starts punching me, then he started ripping the flesh from my side through my clothes.

and

He was choking me so hard I felt the pressure in my face. I thought I was going to pass out. He grabbed my face and dug his claws, his fingernails, in my face.

This is a far cry from Eggers’s glowing depiction of Abdulrahman as a tranquil hero. Eggers describes how “Zeitoun felt at peace,” with “an odd calm in his heart.” Abdulrahman’s origins as a thirteen-year-old fisherman involves a concern for quietude, where his compatriots “would whisper over the sea, telling jokes and talking about women and girls as they watched the fish rise and spin beneath them. Eggers even describes Abdulrahman telling Kathy, “Please be calm. Don’t make it worse,” while approaching a bus station.

It was Kathy’s testimony which led to Abdulrahman Zeitoun’s indictment for attempted first-degree murder and solicitation for first-degree murder during the late afternoon of November 8th. Abdulrahman has remained in jail, with the bail set at more than $1 million. A gag order has prevented Kathy and Abdulrahman’s attorney, J.C. Lawrence, from saying anything beyond their remarks in the courtroom. Eggers is certainly in a position to say something and emerge from this contretemps with some integrity, yet he wishes to pretend as if nothing terrible has gone on. At least that’s what we see on the surface. Under the seams, it’s a much different story.

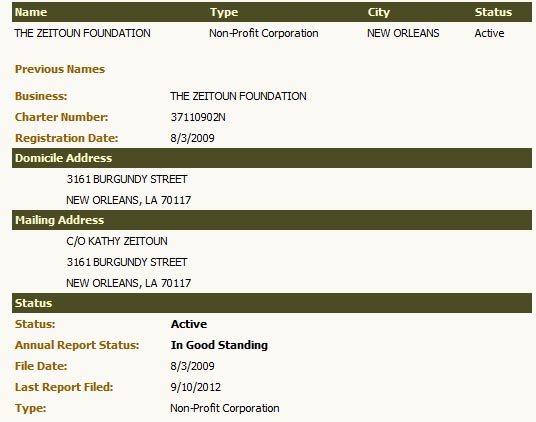

Back in August, we reported on how The Zeitoun Foundation was not being transparent about the way it disseminated funds. While The Zeitoun Foundation is now listed as “in good standing” with the Louisiana Secretary of State (as of September 10, 2012, which is when the last annual report was filed), our search through several nonprofit public databases have not unearthed any new 990s. Furthermore, there isn’t any new information about Jableh, LLC. As we noted in August, Jableh was incorporated on July 16, 2009. It listed Dave Eggers as the registered agent. The 2009 990 for The Zeitoun Foundation declared that $161,331 was due to Jableh, LLC, which exceeded the $145,476 in revenue taken in by The Zeitoun Foundation for that year ($84,044 in royalty income from the book, $50,000 in film rights, and $11,432 in “contributions, gifts, grants, and similar amounts received”). According to Eggers’s book, Jableh is where Abdulrahman Zeitoun was born and lived for a while.

In our efforts to answer these questions, Michelle Quint, the accountable director for Zeitoun, refused to return our phone calls or emails, nor did anybody at McSweeney’s. Eggers had initially released a statement with Jonathan Demme that he and the filmmaker had been “in daily contact with Kathy since the incident on July 25,” but it has since been deleted.

We also received this threatening email from attorney David J. Arrick on August 17, 2012:

Dear Mr. Champion:

The attorneys and accountants who initially set up and continually consult with the Zeitoun Foundation have been made aware of your website.

They would like to clarify that there are two components to The Zeitoun Foundation’s charitable purpose: (1) to aid in the rebuilding and social advancement of New Orleans and (2) to promote understanding between people of disparate faiths around the world, with a concentration on relations between the United States of America and the Muslim world. Therefore, not all of the organizations receiving grants from the Zeitoun Foundation are dedicated to Katrina relief projects.

They would further like to clarify that the Zeitoun Foundation does no active fundraising. The Foundation was created to disburse proceeds from the book, Zeitoun, and to bring attention to the exemplary nonprofits to which it awards grants. To date, outside donations have accounted for less than 10% of all monies disbursed by the Foundation. All other funds have come from proceeds from the book.

While it is believed that The Zeitoun Foundation has been as transparent in its operations as comparable non-profit organizations, it does intend to update the Zeitoun Foundation website in the near future, and will also update all filings deemed necessary and appropriate. The website will provide more detailed information about the grant recipients. The grant recipients are outstanding organizations and the website will share more details about the great work that they’re doing.

Sincerely,

David J Arrick

David J. Arrick, Partner

Boas & Boas LLP

101 Montgomery Street, Suite 1250

San Francisco, CA 94104

Telephone: 415-956-4444

Fax: 415-956-2158

E-mail: darrick@boascpas.com

Website: www.boascpas.com

As of November 14th, the Zeitoun Foundation website has not been updated. Nobody is talking. In two corners of the world, there are more important events going on. A man faces charges of attempted first-degree murder, with his wife still frightened for her life. Another man awaits news over whether he’ll win a prestigious book award, but he has nothing to say about the troubled couple who helped him at a pivotal stage in his career. Without them, he may not have made it inside this swank Wall Street ballroom.

11/18/2012 UPDATE: The Times-Picayune‘s John Simerman reported on November 16th that Eggers and McSweeney’s representatives have refused to answer the newspaper’s questions about Zeitoun.