Any true New Yorker knew who he was: a lean and beatific dancer who you would see around Times Square mimicking Michael Jackson’s moonwalk. He built up a graceful and resplendent performance from a well-known repertoire that Neely owned with his supple and silent dignity. Even if you were in a rush to get somewhere, you’d still need a minute to quietly collect your jaw from the ground after catching the blurs of his flying feet in your peripheral vision. If you were really lucky, you’d be able to see Neely bust out his steps on a subway car barreling between stations, watching him somehow sustain his center of gravity as the train swayed and careened and buckled. All this made him much more than a casual showtime busker hustling for a few bucks. He epitomized the true spirit of this city. And he deserved to live.

Tourists adored him. Gothamites respected him. There is no known method of quantifying the smiles he put on so many faces, but the tally surely must reach into six figures.

What few people knew about Neely — and the sad and enraging thing about this goddamned barbaric business is that it took a murderous Marine with a sick smirk and a passion for chokeholding for us to really know — was that the man was significantly troubled. He was betrayed by a heartless and broken system that left him for dead and that looked the other way as he lived with his pain. It was a pain that broke him. The emotional burden of living with hard and cruel knocks that all New Yorkers know, but that, without resources, becomes an abyss that is almost impossible to climb out from. A pain that had him screaming at the top of his lungs in a subway car on the first night of May, telling anyone who would listen that he was hungry and that he didn’t care and that he wanted to die. The trauma involving his mother being taken from him by a killer who was so cold that he packed her corpse into a suitcase. A pain that involved forty arrests for disorderly conduct, fare evasion, and assault.

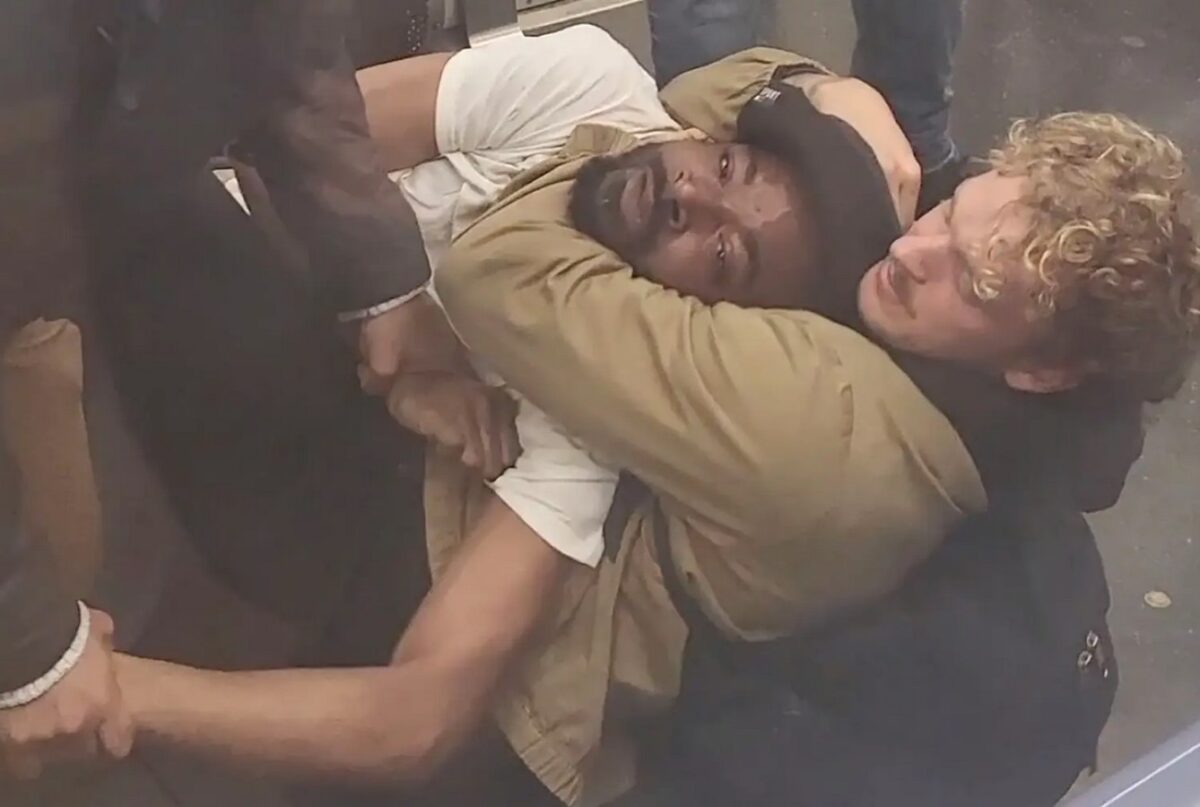

But on Monday night on the subway, Neely was loud but not violent. He was a soul screaming for help. Help that he would never receive. Because the American experiment had rendered him invisible. And that’s when Daniel Penny, an unremarkable blond-haired thug from West Islip on his way to a date, decided to stub out this promising yet troubled light. Penny put Nelly into a chokehold for fifteen minutes. I called a friend trained in hand-to-hand combat, who informed me that you never put someone in a chokehold unless you plan to do serious business to a man. And with this disturbing intelligence, I can only conclude that Penny really wanted to kill a spirit that he savagely and sociopathically considered to be a nuisance. Penny was white. Neely was Black. So he also had that to his advantage.

But Penny also had the American climate in his favor. When a homeless man begs for help in a major metropolitan area, most Americans look the other way. When it comes to mass shootings, we offer “thoughts and prayers” instead of making legislative solutions happen. Lacking a pistol, Penny had his homicidal hands as well as two unidentified aides-de-camp holding Penny’s body down. He also had a scumbag “freelance journalist” by the name of Juan Alberto Vazquez, who never put his camera down even as Neely’s legs stopped twitching. “I witnessed a murder on the Manhattan subway today (there’s video!),” wrote Vazquez on Facebook while caught in the immediate afterglow that a used car salesman feels just after selling a lemon to some gullible mark.

In a just world, the murder of Jordan Neely would stain our city and our culture as much as the Kitty Genovese incident in 1964. It would shame us into actually doing something about it. But we don’t. Instead, we tell people to fend for themselves, accuse the indigent of being lazy and not looking for work, and we reduce SNAP benefits and cut homeless programs instead of putting everything we have into helping the most marginalized members of our society. We endure a colossally stupid and wildly arrogant mayor — the most insipid motherfucker we’ve ever had sitting adjacent to Park Row, a crooked former cop who has deluded himself into believing that he’s “the Biden of Brooklyn” — who has placed a substantive amount of the city’s money into cops — including a projected $740 million in NYPD overtime last year — rather than libraries and parks and affordable housing and mental health services and pretty much any program that would arguably reduce crime more effectively than broken windows bullshit. What was this putzbrained dunce’s remarks after the murder? “Any loss of life is tragic.” “There were serious mental health issues at play.” Followed by self-aggrandizing lies about his administration’s “large investments” in mental health. Which includes, for those not paying attention, authorizing his boys in blue, who aren’t trained to deal with those enduring a mental health crisis, to arrest anyone they deem to be fitting the profile.

Daniel Penny killed Jordan Neely. And he was not arrested. And his name was kept out of the newspapers for three days. Neely didn’t have that privilege.

What makes the Jordan Neely murder so unsettling is how it is the perfect amalgam of problems that our politicians refuse to tackle: racism, white privilege, the mental health epidemic, casual vigilantism, and, of course, the American bloodlust for violence. Republicans and Democrats have badly fumbled the football on these systemic ills and they choose to perceive this tableau of endless suffering as a game rather than a series of events that destroy and even end human lives. In these trying times, anyone with a moral conscience should be seriously considering hitting the reset switch and starting over, letting all these incompetent bastards pay the price in every election across the land. Because if this is who we are and this is what we now casually accept until the next tragedy happens, it’s clear that the status quo isn’t working. We are capable of building something better than this hideous funhouse of endless anguish, but we refuse to learn from France and revolt against these cruel and vainglorious aristocrats until they feel the palpable reality of losing political power.