(This is the fifth of a five-part roundtable discussion of Dana Spiotta’s Stone Arabia. Additionally, Spiotta will be in conversation with Edward Champion on July 20, 2011 at McNally Jackson, located at 52 Prince Street, New York, NY, to discuss the book further. If you’ve enjoyed The Bat Segundo Show in the past and the book intrigues you, you won’t want to miss this live discussion!)

Additional Installments: Part One, Part Two, Part Three, and Part Four

Edward Champion writes:

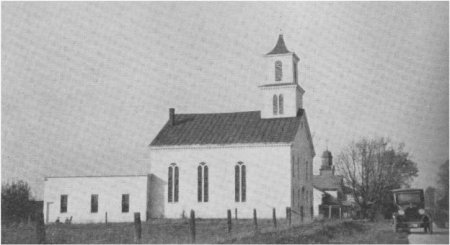

In an effort to address Paula’s question about Stone Arabia’s significance in the Revolutionary War, I located this biography on Google Books published in 1884: Colonel John Brown: His Services in the Revolutionary War, Battle of Stone Arabia.

The first paragraph intrigued the hell out of me:

The residents of the Mohawk valley will ever feel a deep interest in the career of Colonel John Brown, who in the fall of 1780, under the inspiration of a lofty patriotism, came with his Berkshire Levies to this valley, to protect its fields from pillage, its dwellings from conflagration, and its early settlers from the cruelty of a savage foe. This interest is doubtless enhanced by the consideration that when he first engaged actively in the business pursuits of life, he was a resident of this valley, and that he fell while fighting heroically on one of its battle-fields, near which his ashes now repose.

Now doesn’t that sound a bit like Nik’s Chronicles? This got me thinking about whether Nik’s Chronicles represent a new lofty patriotism, or whether the act of plucking a lily (Paula’s question causing me to plunge further, not unlike Ada’s documentary filmmaking) from the vast swaths of electronic fallow is really what Spiotta is remarking upon. If the Battle of Stone Arabia can’t be remembered, if Colonel John Brown’s heroic actions stand no chance of being committed to memory (and we’re arguably living in a nation where our political figures commit more historical gaffes than ever before), then does Nik stand a chance?

Now doesn’t that sound a bit like Nik’s Chronicles? This got me thinking about whether Nik’s Chronicles represent a new lofty patriotism, or whether the act of plucking a lily (Paula’s question causing me to plunge further, not unlike Ada’s documentary filmmaking) from the vast swaths of electronic fallow is really what Spiotta is remarking upon. If the Battle of Stone Arabia can’t be remembered, if Colonel John Brown’s heroic actions stand no chance of being committed to memory (and we’re arguably living in a nation where our political figures commit more historical gaffes than ever before), then does Nik stand a chance?

I’m glad that Susan has brought up one overlooked facet of the book: Denise’s tendency to diagnose from the Internet (Spiotta’s own answer to WebMD?). It’s a woefully insufficient and darkly humorous response to the present healthcare crisis. You don’t have the dough for a doc, but maybe you’ll stand a modest chance with unreliable online info. Perhaps there are unseen Battles of Stone Arabia going on around us —- people dying or getting sick or, in Denise’s case, seeing their emotional life break down because this is the new method with which we survive by our bootstraps. “Pain tourist” is indeed a suitable term.

As Porochista says, even in her refreshingly honest takeaway, it’s not just the points about memory that drive this book. It’s about a place associated with a Revolutionary War battle -— maybe not on the level of Bunker Hill or Valcour Bay -— inevitably transforming into a small hamlet with an Amish contingent (the very opposite of war) without anybody truly observing the changes. So perhaps there remain remain plenty of under-the-radar facets of our culture hiding in plain sight! Like Judith, I feel the impulse to go to the library and drag books off the shelf when there is a name or a memory pertaining to another subject. And yet there’s no way that any Chronicles, or any life, will contain it all! I wasn’t kidding when I said that I would “read forever or die trying” when I threw down the gauntlet for the Modern Library Reading Challenge. Maybe this is why, when it comes to life and it comes to literature, perhaps we really do have the obligation to finish it.

Thanks again to everybody for such a great discussion!

Robert Birnbaum writes:

I read Stone Arabia (a title I expected nothing from) as the story of a savvy and functioning middle-aged white woman narrating (reliably?) the story of her life, which includes an idiosyncratic and increasingly dysfunctional brother, a mother whose faculties (and thus her ability to live independently) are diminishing and a grown-up daughter who seems the healthiest in this cast of characters (she got out and moved away from the family’s melodrama).

In the context of this story, I find Denise admirable for her support, her concern for her kin and for her sensitivity to the outside world (the mother arrested for taking her infant to a bar, her reaction to Abu Ghraib, the Chechnyan school tragedy, and one other instance I have now forgotten). I wonder if any of us had anything more than a a passing reaction…

On the other hand, I don’t have much sympathy for Nik. He may or may not be talented in an accessible way. (And I don’t award him much for his ability to mimic various elements of the creativity business.) I am not certain whether he was easily thwarted by any resistance to his ambitions (on the verge of success, his band was apparently sabotaged by one of those sharpies with which the record business is infested), but his nearly three decades as a barkeep in a Los Angeles dive bar is, at best, evidence of a pathetic lack of self-preservation. His substance abuse, which he refers to as his consolation, provides ample evidence that, whatever the obsession to fantasize a life of creativity means in his life, it does not offer (much) relief for what ails him. Did Nik kill himself? By that point in the story, I had stopped caring.

On the other hand, I don’t have much sympathy for Nik. He may or may not be talented in an accessible way. (And I don’t award him much for his ability to mimic various elements of the creativity business.) I am not certain whether he was easily thwarted by any resistance to his ambitions (on the verge of success, his band was apparently sabotaged by one of those sharpies with which the record business is infested), but his nearly three decades as a barkeep in a Los Angeles dive bar is, at best, evidence of a pathetic lack of self-preservation. His substance abuse, which he refers to as his consolation, provides ample evidence that, whatever the obsession to fantasize a life of creativity means in his life, it does not offer (much) relief for what ails him. Did Nik kill himself? By that point in the story, I had stopped caring.

Denise’s (failed?) relationships don’t strike me as particularly telling, except in the pleasure she derives from escaping into the world of old movies with her useful paramour Jay. Her concerns about her mother’s decline meld into her not unreasonable midlife anxieties of her own mental diminishing. That’s life. She appears to be a caring mother — either I missed it or her bringing up the younger Ada was not part of this narrative.

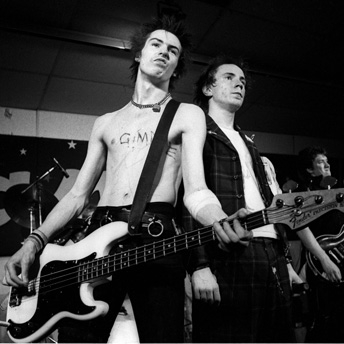

Apparently, Stone Arabia was sufficiently engaging for this group of dedicated readers to call forth a plenitude of analysis and interpretation as well as some brainy cultural references. I thought the title fell slightly short of being useless in my reading and the cover art may have referenced the quintessential punks, the Sex Pistols. But the cutout newspaper typography was not original to them -— not to mention, did I need to get these references to Nabokov and Byron to reasonably enjoy Ms. Spiotta’s meticulously spun tale? Also, while Nik’s (artful?) mimicry could lend itself to hypertextual adaptations and flourishes, I think such gimmickry is incidental.

Hmmm….did I like this book? Not in particular -— though I respect Dana Spiotta’s rendering, I am not much impressed with what I see as Nik’s parroting of the music business. That his sister is devoted and supportive turns out to be too small a story to really engage me. I certainly do not regret reading this and I am pleased to confirm the variegated subjectivity, which I note this group of readers brought to this Medusa-headed conversation.

Darby Dixon writes:

Here’s a handful of tossed-off points, because I can’t help myself:

- Does Jay actually like Kinkade? Or was that more of an ironic thing, a quirky little thing that happens between a couple? I’ll be able to actually review passages over the weekend, but I suspect I either read this point wrong the first time through or I read it way differently than everyone else did.

- How does Spiotta do with endings in general? This is a question for those familiar with her whole body of work. Again, full disclaimer: it’s been a while since I read Eat the Document, but I kind of remember question marks going off over my head around that book’s ending.

- The idea that women should be behind other women writers 100% makes me feel like I need to go read a stack of Tom Clancy novels. I mean, I know, I know. But. (It’s a perpetual point of shame that I’m not reading enough women writers, etc., etc., etc., embarrassed my current stack is male-dominated, etc., etc., etc., to be rectified in the coming weeks/months/years, etc., etc., etc.)

- I like Ed’s notion of Stone Arabia representing an unknown place in plain sight. The history we’ve lost is, what, billions of times more in pure quantity than the history we’ve kept? Reading The Chronicles as a form of patriotism seems a little like a reach to me. Nik is free to do what he wants. And if he wants to spend his life writing a fake story about himself that nobody reads, well, people have died so he can. Are there more depths plunge into here?

- Speaking of Nik (because he’s the flashy guy who can’t help but steal attention from anyone else in the room) has the term “self-portrait” been used here yet? I ask because, in my current drawing class, we’re working on self-portraits. And I spent four hours last night staring at a three-foot-high developing rendering of my own face, Nik couldn’t help but come to mind. His Chronicles are essentially a self-portrait in words, aren’t they? (What’s to stop me from critiquing my own artwork?)

- Speaking of myself -– and by extension, all of us -– on a meta level, I’m totally fascinated by the weird tension between reading the book as a text and reading it as a reflection of ourselves. Not that I have anything interesting to say about that, other than I like it.

- And there are so many other things I want to ponder, review, and discuss further. Ed and all, you may have ruined me for books for which I can’t participate in a roundtable like this. Thank you!

Paula Bomer writes:

Ed: I agree that Stone Arabia is not a random place she picked, nor a random title. Spiotta is far more deliberate than that and she loves hidden meanings.

I thought it was pretty clear that Jay’s love of Kinkade was ironic.

Whether I liked this book or not? I’m happy I read it. I found the second half very engaging. It had some weaknesses, but very few books don’t. Emily Nussbaum wrote that Mary Gaitskill’s first novel “flawed” and disparaged it. I love that novel, love it, and I know it’s flawed. I think Stone Arabia is a very smart book, brimming with the author’s intelligence and compassion. Quite frankly, the flaws are minor in comparison to its strengths. In general, I doubt it’s a book I would have picked up on my own, but I’m very glad I did, thanks to Ed. I should read more things that aren’t my thing (meaning, I need to stop rereading Tolstoy, Greene, Gaitskill, EJ Howard, and so on).

Bill Ryan writes:

Does Jay actually like Kinkade, or was that more of an ironic thing, a quirky little thing that happens between a couple? I’ll be able to actually review passages over the weekend, but I’m suspect I either read this point wrong the first time through or I read it way differently than everyone else did.

We never get a lot of info on whether or not Jay’s in love with Kinkade. We only know that his “obsession” was “pure.” Jay “wasn’t a very good looking guy.” He wore sweaters that gave him “an off-putting, almost creepy diminutive effect.” Just about the only positive thing Denise has to say, other than his between-the-lines, non-threatening nature, is that his obsession is pure. We get that in the Kinkade and the James Mason movies. Denise goes on to say something about how the world is full of “fake obsessions” and there’s little that’s more terrible to her than faking an obsession. We would hope it’s an ironic obsession, but aren’t “irony” and “purity” antonymic?

Denise says, “I am drawn to obsessives.” No shit.

Sarah Weinman writes:

This is both on-track and off-track, but it’s interesting to juxtapose Porochista’s question (“but did you like the book?”) with Darby’s observation about Stone Arabia taking place in 2004, the year of Facebook’s birth, with all the talk of memory and fakery and the sheer number of intense personal narratives we’re sharing (and how I feel tremendously honored to be one of the share-ees, so to speak). Because even though I didn’t think that it was Spiotta’s intention, the mere fact that I’m connecting these disparate strands demonstrates why Stone Arabia is so damn relevant and necessary: it’s a book to admire, that inspires both deep emotional responses, but also this wealth of analysis that travels as far back in the past as 1780 and as far forward as, well, 2011. When we’re all thinking about what it is to be “authentic” and “true” and whether the word “like” has been corrupted by Facebook (and also the word “friend”) when “follower” is now a social media buzzword more than a description of someone leading disciples (which, in this case, means Nik is the cult leader and Denise is his ardent acolyte; I will refrain from stretching this metaphor to needlessly thin Jesus/Paul comparisons, however).

Truth in art has been on my mind — in particular, with respect to documentary films. The last few I’ve seen have really cemented my belief that the form is suspect, that it is impossible to have a reliable narrator, and that facts are wilfully misrepresented and contradicted with a Google search or two. Which, of course, makes fiction “truer” — at least to me. So when Spiotta explores memory, its boundaries, and its limitations, her quest becomes that much more meaningful. Sure, there’s artifice. But there’s also tacit acknowledgment of this artifice. We can’t trust “facts” and “truth.” So why not do something greater, whatever that entails?

Roxane Gay writes:

Does Jay actually like Kinkade, or was that more of an ironic thing, a quirky little thing that happens between a couple? I’ll be able to actually review passages over the weekend, but I’m suspect I either read this point wrong the first time through or I read it way differently than everyone else did.

I didn’t get the sense that Kinkade was an ironic thing that develops between this couple. Because Denise and Jay weren’t that kind of couple. They were all business. So they couldn’t even have the kind of interaction that would make this strain of charming irony and history possible. The way Jay was written makes irony, on his part, rather implausible. Or maybe I just really hate the character and Kinkade so much that I’m hoping there’s no irony in the obsession.

Paula Bomer writes:

Roxane: I’m very curious (and I did try reading all of the comment threads; so maybe you’ve already explained this) as to why you dislike the Jay character.

I think that irony — or kitsch — is implicit in the Kinkade collecting. It serves as a counterpoint to the writing of music that includes “Soundings.” It is the opposite of that sort of “art.” I honestly believe that Kinkade himself made his work with a strong sense of kitsch, knowing that he was mocking “real” art. As little as I know of LA — and I appreciate all the people who have commented on the LAness of this book — people in LA are much more likely to gravitate to this type of art and the collection of items that may seem lowbrow, than the classical musicians I know in Vienna.

I’m going to throw out some ideas that I don’t completely believe. Delillo. Spiotta loves him. I’ve never managed to get through one of his books. My bad, for sure. But let’s say I see this book as a woman’s book wrapped in a man’s book. There could be many reasons to do this. Women’s books are not taken as seriously because they deal with the domestic. Men’s books deal with world issues, with structure and language, and with abstract notions. Hey, men are better at math. So Spiotta utilizes this slightly weird framework, chews on ideas (as opposed to the inner lives of humans). She contemplates ideas of art, the meaning behind these ideas, and history (thanks Ed, for elaborating on the title). She’s mocking, she’s ironic, and so on. But to me, the meat of the book is the story of a damaged family. A woman wrapped in a man. Yet it’s a woman’s voice, wrapping herself around a man’s self indulgent life. There is so much “bothness” in this book — a favorite term of mine, coined by David Foster Wallace.

I read as many male writers as I do female writers. I often feel that male writers — and maybe “often” is unfair, maybe “sometimes” is a better word here — use technique and literary pyrotechnics to avoid getting at the emotions that rule our daily lives.

All of the above is offered to continue the discussion. I’m truly on the fence about it. But I felt the need to throw this out there.

Porochista Khakpour writes:

Paula: Interesting!

Paula: Interesting!

I’m not sure I agree on the gender divide stuff at all ( for one thing no male writer I know has touched Gertrude Stein in levels of experiment). Interestingly enough, I would have killed for more literary pyrotechnics here! The opportunity was there and it was not taken — at least not all the way. She made a gesture in that direction but backed away from really going there…which, yes, my beloved (maybe favorite writer) DFW would not have done. But since I don’t trust today’s big publishing climate, I have to consider, to be fair, that maybe Spiotta wanted things to be more experimental and she was pushed out of it. Who knows? From reading her other book, I’m inclined to think she shied away from it. Even Egan I wanted to be more experimental! We need female experimental writers to be recognized because lord knows they are out there. The industry allows white males to be more wild and intellectual and experimental; the industry recognizes and nurtures the desire in them. So I think we all have to write about things greater than just ourselves and our own personal experience. (I mean, without fail, nine out of ten editors want me to dish on minority female experience, are interested in reading me for anthropological insights on the Iranian-American experience, want to hear me go on about men and dating and relationships because I am still “youngish,” etc.)

And finally, I want to confirm that it’s true that LA people have a high tolerance for cruddy, campy, and kitschy shit. Maybe even Kinkade garbage. But Kinkade, while he must have realized he may profit from the joke, was not originally in on it, I believe. At least that’s what the 60 Minutes segment on him once made me believe.

Alex Shephard writes:

Apologies about entering this (really, really insightful and wonderful) thread so late! I’ve been on vacation this week, and have a sinus infection that’s left me feverish and incoherent. Hope I don’t derail anything.

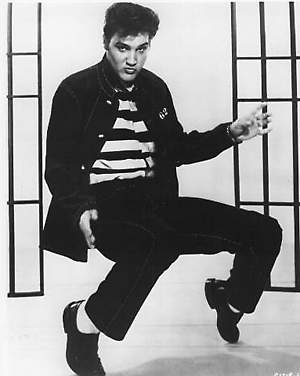

I want to talk about cliche, kitsch, and rock music. From the very first sentence, Nik’s story is explicitly linked to the dominant narratives of the “golden age” of rock ‘n’ roll, the 1960s — “he changed in one identifiable moment.” A Hard Day’s Night is cited by a number of groups (esp. the seminal LA band, The Byrds) as a formative moment in their evolution; similarly, John Lennon and Paul McCartney have linked their decision to begin playing music to a moment just after seeing Jailhouse Rock (“now that’s a good job,” John Lennon would say later about Elvis). The sudden appearance of a guitar, and it’s immediate transformation into an object of obsession, is also inked onto the pages of rock lore. Over the course of Stone Arabia, Spiotta links Nik’s experience — his actual experience (the manipulative managers, the strange left turns, the substance abuse) and his Chronicled experience (the motorcycle crash, “every person who did see them live seemed to have formed a band of their own,” the substance abuse) to dominant (and very cliched) narratives that characterize so many biopics and biographies about rock music, both popular and underground. Interestingly, these narratives, manipulative and often tacked on as they are, are what define the “authenticity” of ’60s and ’70s rock music. It’s why The Killers grew mustaches and went out into the wilderness to record their second album, why The Kings of Leon will always remind you of the fact that they’re all related, and how they grew up traveling the Bible Belt with their preacher father. At this point in time they’re kitsch narratives — harkening back to a time that never really existed, imitating a narrative that was already mostly a lie.

I want to talk about cliche, kitsch, and rock music. From the very first sentence, Nik’s story is explicitly linked to the dominant narratives of the “golden age” of rock ‘n’ roll, the 1960s — “he changed in one identifiable moment.” A Hard Day’s Night is cited by a number of groups (esp. the seminal LA band, The Byrds) as a formative moment in their evolution; similarly, John Lennon and Paul McCartney have linked their decision to begin playing music to a moment just after seeing Jailhouse Rock (“now that’s a good job,” John Lennon would say later about Elvis). The sudden appearance of a guitar, and it’s immediate transformation into an object of obsession, is also inked onto the pages of rock lore. Over the course of Stone Arabia, Spiotta links Nik’s experience — his actual experience (the manipulative managers, the strange left turns, the substance abuse) and his Chronicled experience (the motorcycle crash, “every person who did see them live seemed to have formed a band of their own,” the substance abuse) to dominant (and very cliched) narratives that characterize so many biopics and biographies about rock music, both popular and underground. Interestingly, these narratives, manipulative and often tacked on as they are, are what define the “authenticity” of ’60s and ’70s rock music. It’s why The Killers grew mustaches and went out into the wilderness to record their second album, why The Kings of Leon will always remind you of the fact that they’re all related, and how they grew up traveling the Bible Belt with their preacher father. At this point in time they’re kitsch narratives — harkening back to a time that never really existed, imitating a narrative that was already mostly a lie.

There are Easter eggs — connections to archetypal rock lore — on almost every page of this book, and the relationship between the narratives that run through The Chronicles (perhaps also a nod to that perfect rock “memoir” of (probably) mostly fiction, Bob Dylan’s Chronicles) and the narratives offered by musicians and journalists to explain rock music is crucial to my reading of the novel. What happens when you have a series of fake narratives that echo real ones that both signal authenticity and are, frankly, composed of bullshit? These are narratives that either heighten or diminish reality, that often make reality seem more dangerous and comforting at the same time. This, in my mind, is the connection between Nik Worth, Denise’s anxiety about her memory, Thomas Kinkade, and the “Breaking Event” chapters. Each provides a narrative that converts “real experience” into something that both signals a kind of authenticity and that is kitschy. They all are meant to “identify and fulfill the needs and desires of his target audience,” to borrow a description of Kinkade’s work. The Aladdin Sane birthday cake also illustrates this connection nicely.

Of course, Worth is positively subterranean, and the conflict between life underground and the rock ‘n’ roll dream narratives within The Chronicles is what I find most interesting about Stone Arabia. Nik is as authentically underground as it gets, but both his “real” life and his second life in The Chronicles all mirror cliches. He’s authentically underground, while also exemplifying the inherently inauthentic narratives that determine one’s status as authentically anything. In his interview with Ada, he says “Imagine doing whatever you want with everything that went before you. Imagine never having to give up Artaud or Chuck Berry or Alistair Crowley or the Beats or the I Ching or Lewis Carroll? Imagine total freedom.” Of course, all of those things show up as formative cliches for the Beatles, Dylan, and Morrison (among many others). Perhaps Nik’s project is a way of trying to free himself from anxieties about authenticity itself, an attempt to both hold on to talismans and rid himself of their power? And what is authentic experience anyway? That’s the dominant question of the Breaking Events chapters, and a crucial one within the novel itself.

My fever is back, though. So I’m going to cut off here. A few quick notes before I go:

- When thinking about Nik’s life and music, I kept thinking of people like Brian Wilson, Roky Erickson, Syd Barrett, and Daniel Johnston. Interestingly, all of these artists are mentally ill. I’m not suggesting Nik is mentally ill. I’m just somewhat surprised that I kept instinctively making the link. Did anybody else have that experience? I suppose it may just be that these people all spent significant time “underground.” Arthur Lee, the Godfather of L.A. underground, was also on my mind.

- I have no idea what Nik Worth’s music sounds like. While I had my problems with the Richard Katz sections of Freedom, I ended up getting an idea of what The Demonics and Walnut Surprise (easily the worst fake band name ever) sounded like. His list of influences was diverse (and aweseome! Can, the Incredible String Band, and The Residents? Sweet. He does lose points for hating on Wings, though.). Denise and The Chronicles tend to use genre (or cliche!) as a substitute for description: “power pop,” “progressive” “unique sound to counter to both commercial progressive rock and punk rock,” “dark lyrics and art rock dissonance,” “fatal hooks and crafted melodies,” “unique, intense,” “proto-glam,” “crystalline gorgeous harmonies got them compared to the Beatles,” “perfectly rendered songs of herartache and youth,” “unprecedented path of experiment and innovation,” “full of cryptic and hermetic references,” “Who would have guessed what we were all waiting for was a collection of atonal, arrhythmic assualt compositions mixed with concept sound poems?” “A Futurist sound experiment, a dada poemlet.” That’s just what I found in the first 94 pages. None of it helps me hear Nik’s music, though I do think some of it is relevant to what I talked about earlier.

There are three songs that were on my mind when I was writing this post:

Wilco – “The Late Greats” (The best band will never get signed / K-Settes starring Butcher’s Blind / Are so good, you won’t ever know / They never even played a show / You can’t hear ’em on the radio)

Bad Company – “Shooting Star” (The ultimate rock success cliche song!)

And a parody of the Bad Company song (and others like it) by America’s Beatles, Barry Dworkin & the Gas Station Dogs (as performed by Ted Leo)

Dana Spiotta writes:

Thank you to Ed for doing this roundtable. I am so grateful for all the time everyone put into the discussion. I knew this was a book that would elicit complicated reactions, but I was so pleased to see people found so much to discuss. What thoughtful and interesting responses. How generous you all are to read the book so carefully. With so many books in the world, and so many other things demanding attention, a novelist is extremely lucky to get serious readers.

Thank you to Ed for doing this roundtable. I am so grateful for all the time everyone put into the discussion. I knew this was a book that would elicit complicated reactions, but I was so pleased to see people found so much to discuss. What thoughtful and interesting responses. How generous you all are to read the book so carefully. With so many books in the world, and so many other things demanding attention, a novelist is extremely lucky to get serious readers.

I can’t help imagining Nik getting the roundtable treatment for his life’s work. He would love it. It is glorious to have deep and long attention to your work. But then he would hate it — because you can’t control responses. People bring their whole long lives to it; it is as subjective and complicated as any creative act. That is one of the book’s concerns: artistic creation and response. Nik would have fun making up his own roundtable, and part of the fun I had in writing the book was taking an artist’s desire for control to an extreme. Maybe there’s no one who is more of an obsessive control freak than a novelist. You sit in your room and play god for years. Then you emerge with this crazy thing — not unlike Nik’s Chronicles, which is a kind of long autobiographical novel. You live in this made-up world as you are creating it. Everything you do and are interested in relates to your secret world. At least that is how it works for me. It takes over my dreams and my rhythms and my speech. Its defects become my defects, which can be a little traumatizing. For me, writing novels is a strange and antisocial thing to do. But I feel more attentive and closer to people when I am writing. So it is complicated. In this book I was interested in the world within the world, and the cost of being close to a person who does that kind of work. So the first big question you all asked — is Nik a “real” artist? Of course he is. Who can say he isn’t? Which doesn’t mean he isn’t a narcissistic freak. I was quite deliberate about leaving the quality of his work ambiguous. I was mostly interested in his devotion. The challenge was suggesting this lifelong, hyper-elaborated art piece. (It meant writing as Nik pretending to be someone else, a sort of double fake that still had to be convincing. It couldn’t be boring or badly done. So Nik is as self-reflexive as I am, he likes contradictions and inside jokes. For example, the irony of his wanting to escape criticism but then needing to create a kind of mean snarky critic within so it feels real to him.) I showed various clips from his Chronicles, but I needed to leave a lot out because I wanted, as I describe below, to focus on Denise’s perceptions of it. I wanted to show just enough, but I didn’t want the novel to be the Chronicles. I didn’t want an iPad app with his music and album covers. That is one possible way to go, but I didn’t want to do that. I didn’t want this to be a novel of tricks and games. I really didn’t want it to be cheeky and cute and merely clever. I wanted it to be about being human, about how humans cope with the given terms of this cultural moment, and I wanted it to be about family: the hermetic, complicated, intimate, and relentless idea of family. Even the novel’s very deep concerns about memory and identity are rooted in the strange romance of family.

I am only interested in writing about things I haven’t figured out. In other words, I usually start with a question. And rather than discovering an answer as I write, I try to make the question as deep and complicated and honest as I can. The momentum, if it exists, is in that increasing complication. I think some people perceive this as ambivalence — I tend to undercut everything with its opposite — but I don’t see how anyone meditating on anything deeply can feel only one way about it. People in my novels have strong desires, but they don’t only go in one direction. So I think I begin with ideas, and then it changes as I get into it. In Stone Arabia the inaugural idea was of an artist who doesn’t achieve success in the world, but then he keeps going. And like many isolated artists, he has one person who believes in him and acts as his audience, in this case a sibling. So I wanted to see what that was like twenty-five years in. And I wanted him to be the real deal, but I also wanted him to be a “loser.” I wanted it to be as complex as family is: a long elaborated relationship from which there is no end (or beginning, for that matter).

I started with that. Then, as I was working, I realized that the sister — the audience — would narrate it, had to narrate it. And the thing became a novel of consciousness. As a writer I am really interested in the depiction of consciousness in fiction. I think the novel describes — enacts — the experience of a mind better than any other medium. I also like how a novel is relentless and inescapable the way a mind is. (I really like that you can’t click through to something else. Of course you can always throw the book across the room.) I wanted the book to be claustrophobic and distorted by emotion and doubt and subjectivity. As I worked I wanted the story to be emotional — practically deranged with emotion — but I also wanted it to be unsentimental and uneasy.

All of the structural decisions came out of these concerns. I wasn’t trying to be experimental or conventional. I wasn’t concerned with realism or metafiction or postmodernism. I think of those things as a reader sometimes, but as a writer I try to be more intuitive. I try to “go to the jeopardy” as Gordon Lish used to say (or that’s how I misread him to suit my purposes). I try to be brave about proceeding despite my own shortcomings and limits. All I can do is make myself relentless. My deformations are my own — just go there and go deep. So the form came out of necessity. The form came out of my interest in the interplay of Denise’s consciousness and the idea of a long elaborated fantasy life. Of course the shape also came out of the difficulties, failures, and deceptions of using language as an organizing force. How to tell a story necessarily becomes part of the novel’s deep concerns. Since the novel largely consists of a first person “written” narrative created by a mostly self-taught and self-conscious woman on the edge of emotional collapse, I really needed those third-person narrative breathers (primarily at the end and the beginning) to frame it, even if they never move all that far from Denise’s consciousness. Denise, Nik, and Ada all have specific language strategies. The challenge was in distinguishing all these documents and pieces without losing the connective thread of the human emotion. I don’t know how close I came to achieving my ambitions for this book. But that is what I was going for. I like having everything at stake, and then if I fall short (and I always will), I still end up somewhere interesting.

By the way, I did not see Nik as mentally ill at all. Maybe that shows how crazy I am. He is fully aware of what is real and what isn’t. He is certainly an alcoholic (by an decent standard), but he is unapologetic and I see him as a resister. He has found a way to be the person he wants to be. He seems immune to the judgment of others. He is deeply unconventional and eccentric, albeit very self-obsessed. I admire Nik’s ability to create his own artistic world. He was supposed to quit and get a real job, or he should have gone out and promoted himself. But he isn’t interested in that, and he pays the price. He isn’t bitter — he has been content in his odd way. I personally hate the way novelists are expected to self-promote. How everyone is expected to self-promote. I hate feeling helpless about how to sell books to people. Wah wah wahhh, right? That is another thing Nik has going for him. He isn’t full of self-pity and complaint.

Of course your life is never just your own, and your choices have consequences. I am obsessed with consequences, and what moral — yes — obligations we have to each other. So Nik makes a decision in his life to be intransigent and live at the margins. By the time he is fifty, he is falling apart. I was very aware that these characters lived in America of 2004. A specific time and place. There is no room in the US of recent years for people to live eccentric lives, especially as you age, because of money. Money was one of the big complicating factors. I wanted this to be a book where money weighed on everyone. (I thought of Joyce and how he wanted no one in his books to be worth more than 1000 pounds. He wanted to have Bloom and Stephen counting every penny. He wanted the ultra-realism of money and bathrooms. So far I have left out the bathrooms, but I too have no interest in the lives of the rich.) Health insurance, second mortgages, food stamps, WIC, medi-cal assisted living. I wanted the details of money to play a big role. Because one reason being an artist is so difficult is because of money. And especially without national health insurance, trying to live at the margins becomes nearly an act of suicide as you age. Denise and Nik didn’t get the education they should have had, given their potential. Their mother always had to work, their father left, so they are under parented. They are almost feral children, self-taught and self-raised. Money was clearly a big force against them. I do think being an artist — especially if you are not a mainstream artist, or a born promoter — is harder than ever. I chose Topanga for Nik’s garage because it is one of those American places with a history of off-the-grid artists, a place that encourages eccentricity. Good luck finding a cheap place there now, and good luck trying to live like a bohemian anywhere.

I don’t see Nik as a bad guy. He is just an eccentric human being. Denise gets a lot out of being his sister. She made different choices. She had a kid — which I think made her more responsible as well as more ordinary. But it also gave her so much comfort, and it gave her a concern for the future and the world beyond her own life. Partly the book became about how we manage to comfort ourselves in the face of mortality. As we start to fail, how do we cope? Denise is trying to cope. I think her anxiety gets located in the barrage of information and media she subjects herself to. Another thing that came up in writing the book is the difference between information and art. Nik’s work — whatever its worth — is satisfying and something she understands. She gets all the inside references and it is meaningful to her. She is moved by it. But the flow of intense and relentless information, the bombardment of the external, is really annihilating for her. It is not all that far from Nik’s substance issues. She should resist it, but she can’t. It is destructive. It is chaotic in an infertile way. She becomes stronger when she writes her Counter Chronicles, when she answers back, when she addresses/organizes things with the force of her consciousness. (This is also like novel writing for me, a way to answer back.) Another question the book is interested in is How do we resist the parts of the culture that will annihilate us? How do we stay human? And I think Nik has one way — a kind of retreat — and Denise’s is another. She tries to look at the world and figure it out. She even tries to dive in. The end of the book — the Stone Arabia scene — came up organically. She is, in fact, approaching a different place mentally, and she is also reacting — as Paula said — to her profound grief about losing Nik (and her mother). She leaves her home and reaches — bodily — out in the world. The novel is interested in consciousness, but also how the body relates to memory and mind. Her watching a body fail (Nik) and a mind fail (her mother) puts these connections in high relief. Denise is losing it, and she makes a kind of desperate leap. I wrote that scene slowly and carefully. I knew it was a risk, but it had to happen. Denise tries to reach out beyond herself. And I knew, as it happened, that her desire for connection would fail — of course it would — but I knew she would try. And Stone Arabia was the place where people disappear (her connections are associative), so it tied into Nik, and it was far away and so different from her life. People are like that, we are — we think geography will change our lives. That physical distance will give us spiritual distance. So she fails, but it is touching to me nonetheless. I chose that town because I discovered it driving one day. It felt magical to me. (I suppose I have that magical belief in place as well. If I lived here, I would be different. It is true and it isn’t. Just as Mina runs away in Lightning Field only to return. She has changed and she hasn’t at all.) I was resisting this idea of an epiphany, a revelation. But I also didn’t want it to be simply an anti-epiphany. I wanted her to go, she had to. I wanted it to be a raw gesture. I wanted it to be about our desire for something to change, which we have, and how the idea can almost be enough, failed or not. Stone Arabia itself is an austere, beautiful place with a long, mysterious history. It has this evocative name — both solid and exotic. I love that name, Stone Arabia, and the sound of it, the feel in the mouth as I say it, it draws me in. It is beautiful, which is reason enough. After, Denise goes back to what is left. She steps out so she can step back in. Maybe she can even be somewhat content with what is left. Not the Chronicles — which are almost a burden — but her daughter, her own life, her endurance, her mind.

So the first part of the end is about adult longing, and the last part of the end is about childhood longing.

The very end was intended as a memory/reverie. I wanted to end on the art, the glimpse of transcendence you can get from art. But it is fraught and melancholy, because it is in the deep past. The very end contains a mini version of the whole book — Nik leaves her (or she leaves him). She is alone with her thoughts. I didn’t plan it that way, it just came out and then I noticed it when I read it all together. Young Denise puts on some music she has never heard before from a band she doesn’t know. She goes from her desire for another to her own desire for herself to just pure desire. It is response to art as a kind of salvation, but it is located in longing and a glimpse of possibility. I wanted it to be innocent. I wanted the last note to be the (remembered) innocent longing of a young person.

The book had to end with a memory, as the novel is also a novel of memory (as any novel of consciousness is). She has the physical experience of being in her old house — memory for her is located in the body as well as the mind. Then she has this vivid dream of the past. The irony, of course, is that Denise has an excellent memory. Her fears are not rational. She does remember.

Thank you for reading the book. And thank you if you got through my rambling response to your responses. Writers are the worst readers of their own work, right?

— Dana

PS I agree with Alex that Nik shouldn’t have been hating on Wings. But that was very young Nik. Adult Nik loves Wild Life. (And you are dead-on about Nik’s use of rock-and-roll tropes and clichés. They are deliberately planted all through his Chronicles. I wasn’t sure if many people would get all the references, but it doesn’t matter if you do or you don’t. It made it feel right to me as I wrote it. Nik would have all these tropes in his head and play with them.)

PPS Sorry, I forgot a few things. I meant to say that all the interpretations are interesting, and I wouldn’t want to shut down any possibilities. Novels are meant to mean different things to different people. Explaining a novel also feels like a really bad idea for the novelist. (One last parenthetical: as far as what is given in the book, Nik doesn’t commit suicide. He does kill himself in the Chronicles, but in his real life he just leaves, which is very different from killing yourself. I was toying with this Ray Johnson idea of enacting your own death as an [insane] assertion of art over life. But then I realized Nik can, and would, have it both ways. He would author his own death in the Chronicles [because the Chronicles are high romantic drama], but he would just disappear in his actual life. How could he resist writing his own obituary? It is what he has been working toward his whole life.)

This was fantastic reading–you all have me looking for a copy of this book. Was just really nice to see a literary novel being read so closely and discussed in such detail.

[…] Stone Arabia:A Novel- Dana Spiotta ( Scribner) […]

[…] the basement sort of thing. Anything pre-2000 would work. Some of the people that you mentioned in [a roundtable discussion about Stone Arabia at Edrants] were a lot of the people I had been thinking about, like Roky […]

Wow, I just read through all of this, and enjoyed it immensely! Thanks!

(And I’m glad Spiotta mentioned that Nik didn’t actually commit suicide because I was beginning to worry that I had misread the book.) But a dead Nik in the Chronicles is the same as a gone Nik in real life, so maybe the confusion makes sense?