(This is the eighteenth entry in the The Modern Library Reading Challenge, an ambitious project to read the entire Modern Library from #100 to #1. Previous entry: The Death of the Heart)

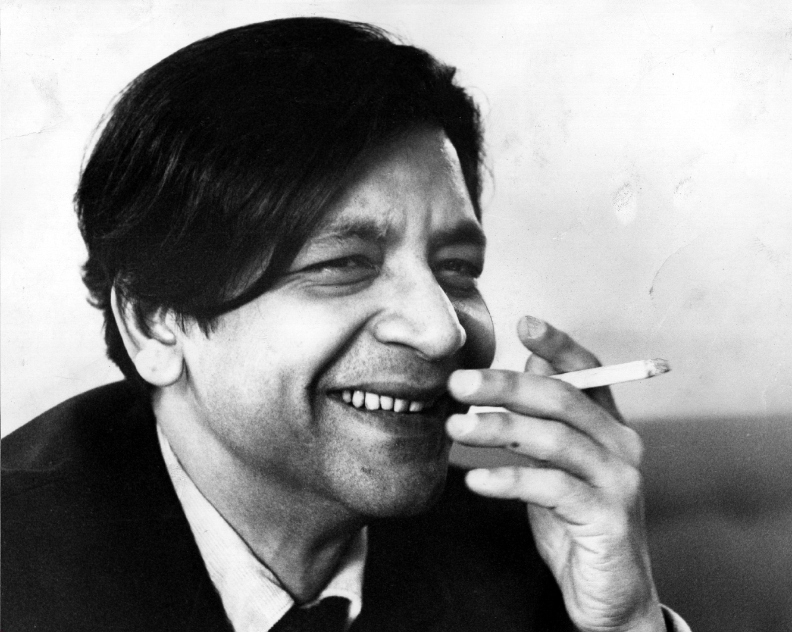

There are so many unpardonable cruelties collected in Patrick French’s gripping (and authorized!) biography, The World Is What It Is, that it’s difficult to know where to start in condemning V.S. Naipaul’s boorish behavior, while also praising his prowess on the page. And yet I can’t quite do that either. I’ve read A Bend in the River twice, and I have to conclude that the book’s pat pronouncements about colonialism, even with the adept take on self-deception and willful naïveté, aren’t especially staggering. By the time the shopkeeper Salim shows his colleague Indar around the African town where he lives and reveals how little he knows (“All the key points of the town I knew could be shown in a couple of hours, as I discovered when I drove him around later that morning”), it was abundantly clear to me that he would never know.

There are so many unpardonable cruelties collected in Patrick French’s gripping (and authorized!) biography, The World Is What It Is, that it’s difficult to know where to start in condemning V.S. Naipaul’s boorish behavior, while also praising his prowess on the page. And yet I can’t quite do that either. I’ve read A Bend in the River twice, and I have to conclude that the book’s pat pronouncements about colonialism, even with the adept take on self-deception and willful naïveté, aren’t especially staggering. By the time the shopkeeper Salim shows his colleague Indar around the African town where he lives and reveals how little he knows (“All the key points of the town I knew could be shown in a couple of hours, as I discovered when I drove him around later that morning”), it was abundantly clear to me that he would never know.

Perhaps the mid-career rise of Naipaul’s rep was all in the timing. French suggests that “[a] rising disillusion with the post-colonial project in many countries lead to Vidia being projected as the voice of truth, the scourge who by virtue of his ethnicity and his intellect could see things that others were seeking to disguise.” But Naipaul does deserve props for depicting how a revolutionary leader (referred to as “the Big Man”), even after the aloof establishment of a McDonald’s-like Bigburger restaurant and a dubious university, steers an unnamed African nation to the same scorched earth which existed before. And this, along with a sad and desperate historian named Raymond and the many ruined monuments seen from previous regimes, makes Bend a rock-hard reading experience for the strident geopolitical junkie. (When I first read Bend, I had this image of Wolf Blitzer shouting aloud passages on CNN, demanding reader responses from Romney and Santorum. I did my best to shake off this terrifying vision of the dreaded bearded bloviator. But my imagination revolted. Because not long after this, I had a weird dream where Blitzer kidnapped me and ordered me to burn all books aside from Naipaul. Blitzer then set himself on fire and began laughing like a psychotic, refusing to let me extinguish the conflagration. And I woke up. This may explain, in part, why it’s taken me many weeks to get to this essay.)

The Andrew Seal types will tell you that the novel’s appeal involves how Naipaul has demonstrated how order is not necessarily in opposition to complexity. And the academic Fawzia Mustafa has rightly suggested that Bend is very much about how one’s relationship to Africa is determined through a misread. (Miscerique probat populus et feodera jungi, a commemorative plague at the dock, is deliberately misread throughout the book.)

But this still doesn’t make up for Naipaul short-changing the African people, who are little more than crude caricatures serving this allegorical exercise. There are marchandes like Zabeth, who pick up supplies from Salim’s store and have “a special smell” that is “strong and unpleasant.” There is the houseboy Ildephonse, who becomes an ad hoc restaurant manager who turns “vacant” when his bosses leave. This leads Salim to conclude:

I noticed this alteration in the African staff in other places as well. It made you feel that while they did their jobs in their various glossy settings, they were only acting for the people who employed them; that the job itself was meaningless to them; and that they had the gift — when they were left alone, and had no one to act for — of separating themselves in spirit from their setting, their job, their uniform.

Granted, the matryoshka-like idea here is that Salim, the Indian émigré who has set up shop and plays squash at the Hellenic Club and is often clueless about how much he is reviled by apparent pals and locals, is the imperialist mirror image to what he sees. The Africans — especially the family servant Metty (nicknamed this because of his interracial background) — develop sentiments that Salim refuses to see. Even outright revolution is beyond his scope. There’s one stirring moment in which Salim visits a school with Indar and is challenged by a student: “Would the honourable visitor state whether he feels that Africans have been depersonalized by Christianity?” Yet Salim refuses to ken these kernels of discontent, later remarking, “I thought how far we had both come, to talk about Africa like this.”

So Naipaul’s novel made for a frustrating experience. On one hand, he wants to expose Salim’s inherent hypocrisy and nastiness. But I have good reason to believe that Naipaul himself embraces it, which is probably why this ugliness smoulders off the page. So while I can admire Naipual’s hard-hitting imagery (“smooth white lips of bread over mangled black tongues of meat”) and his knack for myopic maxims (“We make ourselves according to the ideas of our possibilities” and “The airplane is faster than the heart”), I’d be lying if I didn’t say that I’ve been eagerly anticipating a reading life without Naipaul. (Not quite. Like a Romero zombie, A House for Mr. Biswas is on the Modern Library list at #72.)

A Bend in the River isn’t a bad book. It isn’t as overrated or as desperate to please as Midnight’s Children.* But I don’t think I would call it a classic. While one should take care to separate the author from his work, I have learned that Naipaul has largely drawn from his life. (Indeed, if you read French’s book, it can be handily argued that “V.S. Naipaul” is Naipaul’s favorite subject.) I’ve really wanted to understand why so many people would refuse to question such a flagrant sociopath. Naipaul is a good writer, but he’s certainly not great if we stack the smug scamp against Conrad, Doris Lessing, Chinua Achebe, or Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. All could easily clean Naipaul’s clock.

How has Naipaul mined from his life? One monstrous moment bubbles to the brim. Here’s Naipaul writing his mother in 1956, remarking upon a fellow boat passenger:

Poor thing, she was so frightened at the thought of travelling alone for the first time out of Trinidad at the age of thirty-five. She palled up with me and begged me in case of any alarm or trouble to come and look after her. The red nigger woman is really delightfully simple. You know, in ships, the chairs and tables are all chained to the floor to prevent them from rolling about the place when the sea gets rough. I told the woman that the tables and chairs were chained to prevent people stealing them. And, she believed it. ‘Eh, eh,’ she said, “But look at that, eh.” And again: passengers in different parts of the ship are assigned to different lifeboats (there are 6 on the Golfito). I told her that she had to find out which lifeboat was hers because, in case of any trouble, they were not going to let her get into any old lifeboat. In fact, if they found her in the wrong boat they were going to throw her into the sea. It was, I told her, the origins of the phrase ‘to be in the wrong boat.’

It is already mind-boggling enough to consider anyone who would practice such unmitigated spite towards a woman who was harming nobody. It is another thing altogether to boast about such baleful behavior to your own mother. Naipaul is clearly a man whose central pleasure involves terrorizing any figures “who are nothing” or “who allow themselves to become nothing,” to invoke, as French has with his biography title, A Bend in the River‘s famous opening.

As we read Bend, we learn that the writer and his antihero aren’t terribly different. Here’s Salim responding to poor Ferdinand, when the latter expresses a desire to find a better life studying in America:

I said, “Why should I send you to America? Why should I spend money on you?”

He had nothing to say. After the desperation and the trip through the rain, the whole thing might just have been another attempt at conversation.

Was it only his simplicity? I felt my temper rising — the rain and the lightning and the unnatural darkness of the afternoon had something to do with that.

I said, “Why do you think I have obligations to you? What have you done for me?”

The same question might likewise be addressed to the vile Vidia.

“I love you because you are so mean,” wrote Eve Babitz to Naipaul shortly after Bend‘s publication. But why should we celebrate an author who offers little more than meanness in life and in art? I ponder the type of blindsided reader who would only pine for the negative. Because it sure as hell isn’t me. Sure, I may have been seduced by Elizabeth Bowen’s brand of cruelty in the last installment, but there was enough carefully orchestrated character flinging to keep me intrigued. With Naipaul, the prose was often so slick that I felt my soul being clogged up by a BP-sized oil spill. I haven’t even brought up the unintentionally hilarious affair with Yvette, which is so rooted in preposterous male fantasy that one wonders if Vidia has ever understood women. (This is the same man who has the audacity to claim that women cannot write.)

“Carrying on” may help you negotiate the frontier, but that passive place doesn’t help you connect with other people or overcome your assumptions. That’s certainly Naipaul’s point. Yet I came away from this novel thinking that Naipaul was just as much monstrum horrendum, informe, ingens, cui lumen ademptum as his characters.

* — And since I’m being a little hard on Rushdie, in the interest of balance, I should probably relate this remarkably insensitive Naipaul anecdote. Naipaul has remained so committed to steely misanthropy that he refused to sign a petition supporting Salman Rushdie after Khomeini issued his fatwa, adding (according to the French bio), “I don’t know his books, but I’ve been aware of his statements. I found them usually left-wing and trivial and antiquated.” And he didn’t stop there. Naipaul would call the fatwa “an extreme form of literary criticism.” It’s one thing to dislike Rushdie’s books. It’s another thing to employ one’s literary sensibilities as justification for murder.

Next Up: Wallace Stegner’s Angle of Repose!

[…] Edward Champion looks at V.S. Naipaul’s A Bend in the River, and in doing so shares an incredibly unsettling dream involving Wolf Blitzer. […]

Wow. I mean really wow. I got it!

Arrogant Monster Man! Would it have helped him to suffer at an early age – perhaps that is what is missing?

…

Thanks for having the courage to nail it. I hadn’t read his bio,I’ve only read around him. Narrative from others are now clarified , Theroux is totally redeemed in my eyes.

Gad, I’m probably going to read one of his now, just to peer into the monster’s ‘whatever it is’.

You are right, why bother with the brilliant and petty when we have the brilliant and great.

An excellent perspective from you – just what I like a slice of reality.

…

I just stumbled up on you, but now I’m following. Please continue!!!