It was a good year. It was very good year. It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. It was the age of Britney’s crotch, it was the age of needlessly angry atheists. It was the epoch of Democratic victory in the two houses, it was the epoch of weak-kneed Democrats and other assorted chucklehead politicians.

I’m not sure if any of the above dualisms have to do with the books that rocked my world this year. But I figure that any end of the year list deserves a needlessly portentous introduction. So without further ado, here are the books that I deem The Best of 2006 in alphabetical order.

(In the interests of total transparency, I should note that I have had email volleys with Richard Powers, Jeff VanderMeer and Sam Savage. But I read their respective volumes before I had any detailed communiques with them. So I don’t feel that my opinions here have been compromised. I should also note that Chris Staros was kind enough to send me a copy of Lost Girls, a quite expensive book, but that this had no bearing whatsoever on why Lost Girls made my list. Indeed, I was skeptical with every book I read this year, particularly the titles with hype attached. But the ones here all managed to win me over, irrespective of the circumstances in which I obtained these tomes.)

Alison Bechdel, Fun Home: Some cartoonists (including Bechdel, as it turns out) have remarked to me that they often turn to craft of cartooning as a way to make up for deficiencies on the writing and illustration front, often failing to consider that a natural synthesis of these two forms is also a legitimate craft. Fun Home demonstrates an almost total and perhaps subconscious command of the form. Like many good memoirs, it is also a quest of sorts for identity, with many of the lingering questions remaining unanswered. I particularly love how Bechdel’s overly accurate art accentuates the narrative, with the ephemera of notes and books meticulously reproduced in an effort to find a new meaning. The concern for maps, the constant search for structural clues where there may be none, and the way in which even physical gestures sometimes reveal clues about who Bechdel’s father might have been and how these traits carry on into Bechdel’s adult life make this an essential read.

Alison Bechdel, Fun Home: Some cartoonists (including Bechdel, as it turns out) have remarked to me that they often turn to craft of cartooning as a way to make up for deficiencies on the writing and illustration front, often failing to consider that a natural synthesis of these two forms is also a legitimate craft. Fun Home demonstrates an almost total and perhaps subconscious command of the form. Like many good memoirs, it is also a quest of sorts for identity, with many of the lingering questions remaining unanswered. I particularly love how Bechdel’s overly accurate art accentuates the narrative, with the ephemera of notes and books meticulously reproduced in an effort to find a new meaning. The concern for maps, the constant search for structural clues where there may be none, and the way in which even physical gestures sometimes reveal clues about who Bechdel’s father might have been and how these traits carry on into Bechdel’s adult life make this an essential read.

Mark Z. Danielewski, Only Revolutions: I wasn’t surprised to see Danielewski’s latest book dismissed by many as a pretentious artistic experiment. But I don’t believe that these dismissals do Danielewski’s book justice. And there is no way that I can contain my reaction to this book within a paragraph, but I’ll try.

This is not so much a beautiful bauble disguising a thinly plotted road trip across two centuries, as it is a meticulous history of how language affects culture, and vice versa. The arcane words that Danielewski employs (with strange and often hilarious juxtaposition) suggest that those who chronicle culture and history might be missing some vital terminology as we merrily skip along and make our own existential choices. The book’s offbeat vernacular, when examined through a historical prism, reveals an argot that any casual linguist will be compelled to investigate. The accompanying historical tickertape suggests that humanity might be settling for the greatest hits instead of raw specifics. And what better way to highlight human ignorance than for individuals to “go” instead of die or pass on? What’s interesting is how Danielewski has history (such as the 1918 flu epidemic) affect his individuals on a very personal level. Is it possible that the historians are overlooking the visceral consequences of pain and loss as they settle their gaze upon historical scope? Perhaps this is the spirit of revolution contained within this amazing book, which requires great patience and a great curiosity about human interconnectedness. I’d like to think that the real revolutionaries are those who hope to open their eyes to the stragglers it’s acceptable to ignore. I was haunted by this book for days after I finished it, contemplating the ways in which language might be the very code which unlocks human perception.

This is not so much a beautiful bauble disguising a thinly plotted road trip across two centuries, as it is a meticulous history of how language affects culture, and vice versa. The arcane words that Danielewski employs (with strange and often hilarious juxtaposition) suggest that those who chronicle culture and history might be missing some vital terminology as we merrily skip along and make our own existential choices. The book’s offbeat vernacular, when examined through a historical prism, reveals an argot that any casual linguist will be compelled to investigate. The accompanying historical tickertape suggests that humanity might be settling for the greatest hits instead of raw specifics. And what better way to highlight human ignorance than for individuals to “go” instead of die or pass on? What’s interesting is how Danielewski has history (such as the 1918 flu epidemic) affect his individuals on a very personal level. Is it possible that the historians are overlooking the visceral consequences of pain and loss as they settle their gaze upon historical scope? Perhaps this is the spirit of revolution contained within this amazing book, which requires great patience and a great curiosity about human interconnectedness. I’d like to think that the real revolutionaries are those who hope to open their eyes to the stragglers it’s acceptable to ignore. I was haunted by this book for days after I finished it, contemplating the ways in which language might be the very code which unlocks human perception.

Joe Meno, The Boy Detective Fails: Like Sam Savage (whose Firmin also made this year’s list), I believe Joe Meno is very much interested in narrative as a metaphor depicting how playfulness is often at odds with adulthood. To what degree can one escape into a past occupied by a playful and perhaps overly sunny mythology? On the flip side, if one conforms entirely to adult responsibilities, how much of one’s identity and ambition does one lose? Meno raises these questions while giving us a very touching and highly entertaining book (which even comes with a decoder ring and a secret message contained within the footer!). His “Boy Detective,” once a promising Encyclopedia Brown-like character, is now stalled at the age of 30. His detective skills have atrophied and he is faced with crushing responsibilities and demons of the past. Meno surrounds his protagonist with other former child superstars, now working soul-crushing jobs at ratty telemarketing firms and movie theaters, while also offering children with which the playful torch may or may not carry onward. This is no small achievement.

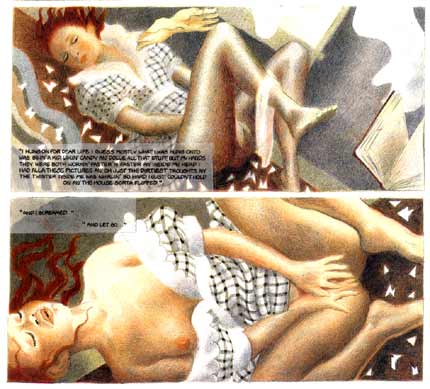

Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie, Lost Girls: I’m sorry that I was never able to offer a thorough review of this three-volume set, but I shall do my best to offer a precis. One does not approach an Alan Moore volume lightly, even when, in Lost Girls‘ case, it seems as if it’s merely an episodic series of sexual reminiscences. But it is a rare talent who can both titillate and cause one to become slightly uncomfortable at the same time. And this is Moore’s point. It is this dual emotional feeling, the idea that one person’s wicked sexual fantasy might make a person “bad,” that has not only led humans to stifle their possibilities, but perhaps, as juxtaposed against the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, led them to the brink of war or, with Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring,” paganist art which begets paganist behavior. Whether one agrees or is titillated by the fantasies contained with Lost Girls is not the point. The idea here, and it is carried out through many ironic associations of staid narratives (dry letters, often preposterous texts, erotic stories) with unbridled sexual activity, is that humans are in the dark about their true “deviant” nature, pushing these away into fairy tales (why else would Moore pull another Wold Newton on us and give us The Wizard of Oz‘s Dorothy, Peter Pan‘s Wendy, and Alice in Wonderland as his protagonists?) but sometimes not giving themselves the liberty to accept fantasy in their quotidian existences. What then is the true pornographic act? Banning tales that are honest about dark human impulses or denying that they exist? Like the narrator-as-guide that William T. Vollmann often employs in his work, Melinda Gebbie’s beautiful artwork serves as a safety net for the troubled reader, ensuring that the universe that the reader is entering here is a safe and valid place. Moore and Gebbie accomplish all this without coming across as shock artists. I was jesting earlier this year when I suggested that Lost Girls was “fun for the whole family,” but I believe anyone looking to uproot their notions of what is considered “abnormal” might want to give this handsome set a chance.

Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie, Lost Girls: I’m sorry that I was never able to offer a thorough review of this three-volume set, but I shall do my best to offer a precis. One does not approach an Alan Moore volume lightly, even when, in Lost Girls‘ case, it seems as if it’s merely an episodic series of sexual reminiscences. But it is a rare talent who can both titillate and cause one to become slightly uncomfortable at the same time. And this is Moore’s point. It is this dual emotional feeling, the idea that one person’s wicked sexual fantasy might make a person “bad,” that has not only led humans to stifle their possibilities, but perhaps, as juxtaposed against the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, led them to the brink of war or, with Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring,” paganist art which begets paganist behavior. Whether one agrees or is titillated by the fantasies contained with Lost Girls is not the point. The idea here, and it is carried out through many ironic associations of staid narratives (dry letters, often preposterous texts, erotic stories) with unbridled sexual activity, is that humans are in the dark about their true “deviant” nature, pushing these away into fairy tales (why else would Moore pull another Wold Newton on us and give us The Wizard of Oz‘s Dorothy, Peter Pan‘s Wendy, and Alice in Wonderland as his protagonists?) but sometimes not giving themselves the liberty to accept fantasy in their quotidian existences. What then is the true pornographic act? Banning tales that are honest about dark human impulses or denying that they exist? Like the narrator-as-guide that William T. Vollmann often employs in his work, Melinda Gebbie’s beautiful artwork serves as a safety net for the troubled reader, ensuring that the universe that the reader is entering here is a safe and valid place. Moore and Gebbie accomplish all this without coming across as shock artists. I was jesting earlier this year when I suggested that Lost Girls was “fun for the whole family,” but I believe anyone looking to uproot their notions of what is considered “abnormal” might want to give this handsome set a chance.

Richard Powers, The Echo Maker: I’ve repeatedly sung the hosannas of this book. So I’ll just direct you to what I scribbled over at Mr. Magee’s.

Sam Savage, Firmin: I picked it up at BEA. The only thing I knew about it was that this was a story told from the perspective of a rat. I figured that, at the very least, this would be great airplane reading, something that might serve in lieu of or, if mediocre, in addition to those tiny little bottles they charge you too much money for. After all, the book was slim and, given BEA’s commercial atmosphere, a tale told by a rodent seemed only fitting on the way back to San Francisco.

I was entirely unprepared to read a wry and remarkably thoughtful book about the state of imagination in American society. The book had teeth, perhaps a continuously growing set of rodent-like incisors ground to manageable size so that the teeth in question wouldn’t puncture the brain. Sam Savage had kept the page count lean, but certainly hadn’t skimped out on the thoughtful ambiguities beyond it.

I was entirely unprepared to read a wry and remarkably thoughtful book about the state of imagination in American society. The book had teeth, perhaps a continuously growing set of rodent-like incisors ground to manageable size so that the teeth in question wouldn’t puncture the brain. Sam Savage had kept the page count lean, but certainly hadn’t skimped out on the thoughtful ambiguities beyond it.

I don’t believe there’s any way to describe the book without it sounding preposterous, but the book concerns itself with Firmin, a rat who, through mere taste, has the capacity to read literature at an astonishing rate. He scurries through Boston’s infamous Scollay Square, just before the square was cemented over by the City of Boston, attending peep shows and exploring the interconnected buildings, in search of food and in search of meaning. Abandoned by his family and unable to interact with his humans, save through recurrent allusions to people he’s “talked to” at bars, he retreats instead into books, finding solace and a new existence. A pulp science fiction writer named Jerry Magoon takes Firmin under his care, offering compassion and unintentional enlightenment. But residing at the center of all of this is a more troubling dilemma: Firmin is alone and books serve as a way, perhaps the only way, for him to subsist.

The books, however, are Firmin’s downfall, as apocalyptic in nature as Scollay Square’s sad fate and Magoon’s visions. Even from the onset, Firmin cannot settle upon a proper first line to describe his story. That Firmin himself boasts of gorging upon the books instead of understanding what’s inside them suggests a character willing to grope at anything to fight a terrible isolation that he is often vague or disingenuous about. And could it be that the tale we are reading here is not one written by a rat, but one of an outcast so thoroughly ignored by society, that he is reduced to feeding on humanity’s leftovers?

That Savage suggests all this without sacrificing his panache for gallows humor (such as Firmin’s first experience with rat poison pellets) is a testament of his talent. Firmin challenges our narrative assumptions by presenting us with a tale told by a rat, signifying perhaps both nothing and everything, about the relationship between reality and fiction. It can be read as a literal entertainment or a multilayered parable about gentrification and the palliatives and pitfalls of imagination.

Dana Spiotta, Eat the Document: Again, I don’t wish to sound like a broken record, but I direct you to my post from February.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o, The Wizard of the Crow: For whatever reason, and I suspect it had something to do with my mixed feelings about Pynchon’s Against the Day, I didn’t expect to be bowled over by this book. But I found myself greatly enjoying this satire of a postcolonial African dictatorship, which reads, at times, like an epic version of Duck Soup. If you are a fan of comedy that hinges upon cause and effect, then Thiong’o delivers the goods, showing how a squatter’s casual effort to find a place to crash transforms him into “The Wizard of the Crow,” a man loved and feared by the very forces who oppress him. I’ll have more to say about this book, when it’s discussed by the Litblog Co-Op.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o, The Wizard of the Crow: For whatever reason, and I suspect it had something to do with my mixed feelings about Pynchon’s Against the Day, I didn’t expect to be bowled over by this book. But I found myself greatly enjoying this satire of a postcolonial African dictatorship, which reads, at times, like an epic version of Duck Soup. If you are a fan of comedy that hinges upon cause and effect, then Thiong’o delivers the goods, showing how a squatter’s casual effort to find a place to crash transforms him into “The Wizard of the Crow,” a man loved and feared by the very forces who oppress him. I’ll have more to say about this book, when it’s discussed by the Litblog Co-Op.

Scarlett Thomas, The End of Mr. Y: Scarlett Thomas is, as I have suggested many times this year, the contemporary to second wave prodigious fiction authors along the lines of Colson Whitehead. Like Rupert Thomson’s great works, Thomas gives us a very unusual premise (a book which may or may not open up a portal into a strange dimensional universe called the Troposphere) and makes us believe in it. This is not mere faux intellectualism like The Matrix movies, but a thoughtful and entertaining meditation on human decision, human potential, interconnectedness and overthinking that left me crushed at the end. Thomas’s protagonist is a fascinating portrait of contradictions: a young doctoral candidate meekly pursuing intellectual interests yet throwing herself into sordid sexuality and allowing herself to be abused. Don’t listen to Booklist’s Allison Block, who dismissed this novel as “chick lit for nerds.” This is a hell of a lot more, provided that you’re willing to go along for the ride.

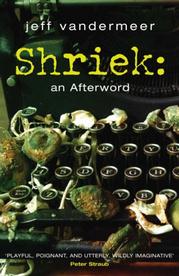

Jeff VanderMeer, Shriek: An Afterword: I must thank Matt Cheney for turning me on to the talented writer Jeff VanderMeer, a man who I had been intending to read for some time. Shortly after Mr. Cheney hooked us up, Mr. VanderMeer surprised me with a prodigious package of his books in the mail and I found myself gleefully lost in his world of Ambergris, a Gormenghast/New Crobuzon-like universe in which humans and mushroom dwellers co-exist with often pernicious results. But it is with Shriek that VanderMeer has truly found his voice, reapproaching his world with a fresh and pleasantly surprising maturity. This is not mere fantasy, but a fascinating hybrid of postmodernism and a reinvention reflecting the turbulent times we now live in. The book features two narrators: Janice Shriek, a parvenu in the art world who casts aspersions on her brother’s underground scholarship. But it is her brother Duncan who gets something of the last laugh, annotating his sister’s revelations with parenthetical comments of his own.

Jeff VanderMeer, Shriek: An Afterword: I must thank Matt Cheney for turning me on to the talented writer Jeff VanderMeer, a man who I had been intending to read for some time. Shortly after Mr. Cheney hooked us up, Mr. VanderMeer surprised me with a prodigious package of his books in the mail and I found myself gleefully lost in his world of Ambergris, a Gormenghast/New Crobuzon-like universe in which humans and mushroom dwellers co-exist with often pernicious results. But it is with Shriek that VanderMeer has truly found his voice, reapproaching his world with a fresh and pleasantly surprising maturity. This is not mere fantasy, but a fascinating hybrid of postmodernism and a reinvention reflecting the turbulent times we now live in. The book features two narrators: Janice Shriek, a parvenu in the art world who casts aspersions on her brother’s underground scholarship. But it is her brother Duncan who gets something of the last laugh, annotating his sister’s revelations with parenthetical comments of his own.

Honorable Mention:

Kate Atkinson, One Good Turn

Richard Ford, Lay of the Land

Edward Jones, All Aunt Hagar’s Children

Claire Messud, The Emperor’s Children

David Mitchell, Black Swan Green

Sarah Waters, The Night Watch

What a great list – I want to read all of these! I love Alison Bechdel’s comic strip, I didn’t know know she wrote a book.