(This is the thirty-eighth entry in the The Modern Library Reading Challenge, an ambitious project to read the entire Modern Library from #100 to #1. Previous entry: The Catcher in the Rye.)

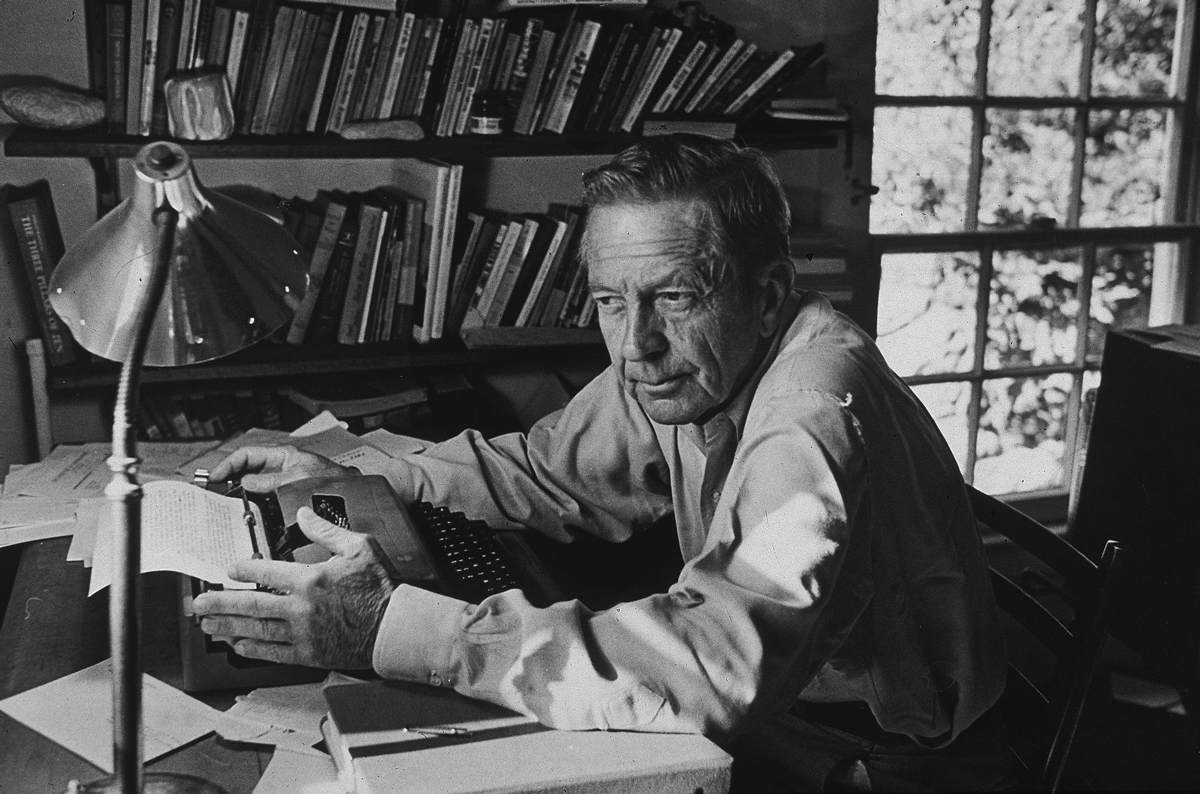

Despite focusing almost exclusively on the upper and middle classes in his fiction, John Cheever was that rare New Yorker regular whose short stories never came across as off-puttingly imperious, superficially urbane, or especially pretentious (although he did don a mannered Mid-Atlantic accent for his television appearances; his 1981 appearance with John Updike on The Dick Cavett Show is highly recommended). But to be fair to Cheever, this Quincy native was also good for a number of gentle tales featuring small-town types trying to live out their grandiose dreams in the big city, as seen in “O City of Broken Dreams” and “Clancy in the Tower of Babel.”) One gets the sense from Cheever’s stories and his diaries that, for all of his hard drinking and his tormented sexuality, the man genuinely loved people and marveled over bizarre jewels mined from the commons. His writing voice led many to call him “the Chekhov of the suburbs,” although that appellation doesn’t do full justice to Cheever’s stratospheric talent or surprising range.

Despite focusing almost exclusively on the upper and middle classes in his fiction, John Cheever was that rare New Yorker regular whose short stories never came across as off-puttingly imperious, superficially urbane, or especially pretentious (although he did don a mannered Mid-Atlantic accent for his television appearances; his 1981 appearance with John Updike on The Dick Cavett Show is highly recommended). But to be fair to Cheever, this Quincy native was also good for a number of gentle tales featuring small-town types trying to live out their grandiose dreams in the big city, as seen in “O City of Broken Dreams” and “Clancy in the Tower of Babel.”) One gets the sense from Cheever’s stories and his diaries that, for all of his hard drinking and his tormented sexuality, the man genuinely loved people and marveled over bizarre jewels mined from the commons. His writing voice led many to call him “the Chekhov of the suburbs,” although that appellation doesn’t do full justice to Cheever’s stratospheric talent or surprising range.

This emphasis on pedigree has caused many contemporary readers to align Cheever — much to the understandable chagrin of The Millions‘s Adam O’Fallon Price — with the equally great Raymond Carver, whose penetrating portraits of blue-color realism showed a similar talent for exhuming the irresistible madness buried within the quotidian. (Carver’s baker in “A Small, Good Thing” — with the surreal quality of his incessant phone calls to a grieving couple — could be a Cheever character. And indeed, Cheever and Carver were drinking buddies.) But Cheever worked a slightly less verisimilitudinous room that, even with its quasi-fantastical wainscotting, proved just as truthful as Carver’s grit. Cheever’s finest stories — “The Enormous Radio,” “Torch Song” (one of my personal favorites), and “The Swimmer” — nimbly corral the motley flocks of common anxieties into quietly surrealistic pastures situated somewhere between speculative fiction and magical realism. But Cheever’s bold storytelling strokes (a radio that airs the conversations of neighbors, people who age or who never age in strange ways) never seem to come across as overly conceptual or call attention to themselves because his characters are so vivid in their behavior. (“I wish you wouldn’t leave apple cores in the ashtrays,” says one of the overheard people in “The Enormous Radio,” “I hate the smell.” As a former smoker who practiced significant pulmonary zest while slowly killing himself, I’ve never seen anyone do this — not even the chain-inhaling slobs I shivered outside with in my dorm room days.) It’s an emphatic lesson that seems to have eluded priapic spec-fic hacks like David Brin, Orson Scott Card, and John Scalzi, who are more interested in bloviating and showing how “clever” they are rather than practicing the art of writing fiction, much less humility, in any notable manner (and, in Card’s case, a monotonously homophobic one).

Buoyed by his elegant and subtly expansive prose, Cheever somehow inoculated himself against being typed — especially after the success of The Wapshot Chronicle, the masterpiece on the Modern Library list which beckons this essay and the novel that got me so passionate about Cheever again that I reread the full oeuvre, delaying yet another installment and once again hedging the unknown number of days I have left in my life against the completion of this insanely ambitious project. Bullet Park is a laudable though not entirely successful effort to break out of the zany New England métier. But Falconer? That novel is a fucking knockout that truly shows just how much range Cheever had. He captured the speech and mannerisms of prisoners in a way completely beyond the abilities of Updike or, for that matter, many of the smug and privileged novelists you see on BlueSky boasting daily about how “woke” they are, even as they can be observed in real life nervously crossing the street whenever they see a Black person approaching them. Decades before Alan Hollinghurst, Cheever had this knack for describing the seedier pastimes of sexuality as if this was the most beautiful thing in the world. But he also rightfully earned respect from the mainstream literary establishment at a time in which writers wrangling with anything even remotely high-concept were often pushed needlessly and ignominiously into the dodgy shadows of the pulp markets.

While Cheevermania thankfully remains somewhat alive in the 2020s — with both Mary Gaitskill and Emma Cline stumping for him at the last New Yorker festival — note how Vulture reporter Brandon Sanchez emphasizes the short stories while shutting out the novels. Even my fellow Cheever booster O’Fallon Price, who rightly points to the “binary choice between dull routine and utter chaos” frequently explored in Cheever’s fiction, offers nothing more than an oblique reference to Bullet Park in his Cheever essay. None of these people seem to have heeded the wisdom of the late great critic John Leonard, who demanded that we express love and generosity to a sui generis talent (just as he did in his review of Cheever’s final novel, Oh What a Paradise It Seems, which is still very solid Cheever, particularly the ice skating and supermarket scenes).

The Wapshot Chronicle is utterly breathtaking, often very funny, and poignant. Less seasoned readers have dismissed Wapshot as the work of a “master short story writer teaching himself how to write a novel” and, while they are not wrong on this point, I think this is a significant underestimation of what Cheever has accomplished here. Wapshot deserves to be held high with the same adulation reserved for his short stories. For one thing, Wapshot is also the first Book of the Month Club selection with the word “fuck” in it. This “transgression,” which must have scandalized pearl-clutching moralists of the lowest order, surely gives Cheever a small amount of punk rock streetcred.

Avoid kneeling in unheated stone churches. Ecclesiastical dampness causes prematurely grey hair.

That silly advice comes from retired sea captain, endearing crank, and old patriarch Leander Wapshot. Stylistically speaking, Leander’s fascinating clippy patois is what stands out on the first reading. But there’s also a shrewd piss-take on Booth Tarkington‘s device of an omniscient storyteller who makes his presence known with picayune details of family lines and furtive glimpses into certain subcultures:

It is the perhaps in the size of things that we are most often disappointed and it may be because the mind itself is such a huge and labyrinthine chamber that the Pantheon and the Acropolis turn out to be smaller than we had expected.

Wapshot was not the first time that Cheever used this trick. His 1955 story “Just One More Time” does this as well. But with Wapshot, the almost satirical formality serves to create an epic structure for the eccentric Wapshot family to run wild. (And in the case of Leander’s two sons, Moses and Coverly, they literally flock to many corners of the nation — particularly Coverly after he becomes a Taper and is sent to far-off regions: the military base, in Cheever’s hands, is sent up gloriously and Cheever would continue with this in The Wapshot Scandal by satirizing the McCarthy trials.) Much like the fantastical concepts in his stories anchored strange behavior, so too does the Tarkingtonesque narrator frame the family adventures.

I also loved the marvelously quirky Cousin Honora, who controls the family pursestrings and who has a highly unusual method of paying for her bus fare:

Honora doesn’t put a dime into the fare box like the rest of the passengers. As she says, she can’t be bothered. She sends the transportation company a check for twenty dollars each Christmas. They’ve written her, telephoned her and sent representatives to her house, but they’ve gotten nowhere.

My only minor quibble about Wapshot — and this is a point that a certain misogynistic predator who was forced to bail from the publishing world lacked the acumen to consider — is how Melissa, the woman who marries Moses, is short-changed by Cheever. It’s clear that she is not happy in the marriage. Cheever, to his credit, would make a noble stab to atone for this in The Wapshot Scandal by having her run off with a 19-year-old grocery boy named Emile. But even in the sequel, I felt that Cheever didn’t quite flesh out this character. It’s not that Cheever couldn’t write women (see Honora, for one) or didn’t understand what it was like to be trapped in a thankless marriage. (Julia Weed in “The Country Husband” is a far better portrayal of this problem than Melissa.) But sometimes the best pilot can’t always stick the landing. And I’m not about to pull one of those Zoomer hissy fits and cancel Cheever simply because he fumbled an important issue. Especially because there’s so much to admire about Wapshot: its wit, its heart, the way that it embraces certain strains of Southern literature only to abandon this tone once Moses and Coverly go off and live their lives, its beautiful depiction of naivety at every age, and the hilarious tally of weird accidental deaths. I also feel obliged to point to Steven Wandler’s interesting essay in which he argues that the two Wapshot novels are similar while presenting contradictory views of the world. Another literary Ed — one who has greater cachet than this irksome Brooklynite — has made a savvy argument that much of this stemmed from the contradictions of Cheever’s life. And aren’t contradictions exactly the reason why we reread great novels?

Next Up: James Jones’s From Here to Eternity!