I observed the following on the subway home on Wednesday night (at approximately 10:30 PM):

- A burly man reading a science fiction novel (spaceship on cover, title and author occluded)

- A middle-aged woman studying her Playbill

- A man in his forties doing the New York Times crossword

- Two additional people (man and woman) studying Playbills

- A woman reading US

- A man, approximately 30, reading a wedding magazine (with his bride-to-be reading over his shoulder)

- A twentysomething reading Metro

- An MTA worker reading a John Scalzi mass-market paperback

- A man, approximately 40, reading Newsweek

- A thirtysomething man reading the Voice

- A guy who was roughly 30 reading the Daily News with iPod earbuds hooked into his head

- A woman reading US News & World Report

- A woman in her 40s reading The Economist (side note: she wore bright golden heels and fiercely turned the pages of her magazine)

- A bald man in his early 30s, his lower lip upturned into serious intent, reading a Star Wars hardcover

- A woman in her mid-twenties reading an unidentified mass market paperback

- A man in his late forties with a strange beret reading The Onion (strangely, he did not laugh once)

- A twentysomething woman writing in her notebook, her legs folded up, taking up two seats

- A man with dreads reading an issue of Better Homes and Gardens

- Approximately 54 people who were not reading, with 24 of them talking with each other, two of them making out like libidinous bandits, and 10 dozing off. This left about 18 people who weren’t reading at all, staring into space or otherwise just waiting for their respective stops. (Additionally, one very attractive woman in her late twenties, observing that I was taking notes, gave me a big smile and unfastened one of the top buttons of her blouse. I presume that she did this because she didn’t have any reading material. I blushed and moved to the other end of the car.)

So here we have 19 people reading on a late evening. Not a bad number at all. And while this data is empirical, this is a bit better than the jejune empiricism rattled off by Daniel Mendelsohn at the New York Public Library earlier in the evening.

“You never see people reading books, magazines, and newspapers on the subway,” said Mendelsohn. He offered this claim because he personally never saw anyone reading on New Jersey Transit. Which led me to contemplate just how frequently Mr. Mendelsohn used the subway and how he arrived at this conclusion. Cavalier instinct, one presumes. What one wants to see, one conjectures further. Whatever the motivations, this was just one of many foolish sentences uttered by Mendelsohn before a crowd. Despite the sold-out audience, the house seemed stacked against the idea that people weren’t reading. And it was a telling sign that even moderator Pico Iyer had to confess to the audience, “You’re almost suggesting with your presence that the book has a future.”

Mendelsohn was there with Iyer and James Wood to answer the question, “Does the common reader exist in our world of spitting screens?” But the words “common reader” — meaning that type of reader I observed on the subway — never came up again during the discussion. As such, the conversation was something of a missed opportunity, with the usual prattle about blogs and literary posterity subbing in for crackling literary discourse.

Iyer lobbed a number of semi-thoughtful softballs to these two noted book critics. He observed that “broken” was in the title of both Mendelsohn and Wood’s books and asked Wood if he wrote about any subjects other than literature. The answer was no. Wood noted that while, for example, he knew about music, he felt unqualified in some way to write about music, and that his energies were now focused exclusively on books. He quoted Kierkegaard: “Purity of heart is to will one thing.” He noted that sometimes he could choose books for review and sometimes the books were chosen for him. Talking about his most recent book, How Fiction Works, he pointed out that when he was 20, he wanted a writerly text that served as a general guide to the world. And aside from Kundera’s three critical works on the novel and the more dated E.M. Forster volume, Aspects of the Novel, he couldn’t think of another contemporary book that solved this problem, that provided “the help that one needs.” “One needs company,” observed Wood. But that evening, he did find cheery comrades in Iyer and Mendelsohn.

Mendelsohn then said that he wished he had a conscious plan for what he did, but he didn’t. He entered book reviewing because of his training as a classicist. Indeed, “training” was one of Mendelsohn’s key crutch words that evening. He observed that a good critic needed to look at everything that surrounded a book. “You don’t just read Homer and not look at Bronze Age implements,” he said. “You can’t focus on Euripedes and not know about the Peloponnesian War.” As a testament to his proclaimed powers of context, he pointed out how he had played the 9/11 card when writing about Alice Sebold’s The Lovely Bones.

But if a real critic requires scope, why then did Mendelsohn speak in such an uninformed way about the blogosphere? When Wood and Mendelsohn were asked about how the critical community had changed in the past 40 years, Mendelsohn said that the critics of yesteryear “never had any competition. There wasn’t 30 million people with laptops telling us what they think of Moby Dick.” Mendelsohn, with the finest elitist hauteur that 2004 had to offer, bemoaned the idea of not knowing who to trust. “Now for the first time, anyone can publish.” And while he was careful to delineate that the Internet is a printing press, neither good or bad, he certainly had it in for blogs, declaring that there was no authority and no responsibility. “Why have a thing that’s wrong buzzing for 30 million?”

In fairness to Mendelsohn, I actually do agree with him that we’ve now reached a point where the blogosphere should strive for accuracy. This very issue was indeed a talking point when I interviewed Markos Moulitsas for The Bat Segundo Show. But if Mendelsohn desires scope in criticism, why then was he not so content to practice what he preached? He kept tossing around this random “30 million” number, as if every blog received a mass audience.

“It’s like me opening a blog on brain surgery,” said Mendelsohn. He didn’t believe that what he styled opinions were true criticism. “You can’t just say anything about anything,” boomed Mendelsohn, who then declared that he wouldn’t dream of publishing without rigorous training.

Let us ponder the delicious irony of that last sentiment. Here is Mendelsohn, a man who is trained in Classics, deigning to put forth an opinion on technology. And if Mendelsohn is trained in Classics, does this not then disqualify him from writing about contemporary literature, theater, or Oliver Stone? After all, he is not trained in these subjects. If he is to remain, by his own definition, an authentic critic, should he not then shut his trap when it comes to blogs? Or on any other subject that he is not “trained” in? If by his own admission, he should not write about brain surgery, then surely he should not gab about blogs. But Mendelsohn did point out that he had bought an Amazon Kindle for a relative and suggested, perhaps jocularly, “I guarantee in 100 years, that’s what he’ll be reading on.”

When a question came late in the evening from the audience about whether the critic could truly judge a novel that its author understood better than the critic, both Mendelsohn and Wood agreed that this was a moot point. Said Mendelsohn, “If a critic can’t judge [a film] because he’s not the filmmaker, then how can the audience?” By this measure, if a “trained” critic understands a book as much as an “untrained” critic (a blogger, for example), then should the questions of qualifications even be an issue? Does a critic really even need to be trained? Should not the criticism itself be the thing that matters?

Wood offered some resistance to blogs, but confined his gripes to comments. “There, I think the rule is sanctioned ignorance,” said Wood. And while he outlined a generalized pattern of how people react to a review that I felt fallacious, the difference between Wood and Mendelsohn is that the former was willing to give the format a chance and try to understand it, while the latter was happy to nuke the site from orbit like an uninformed cretin.

Wood offered some resistance to blogs, but confined his gripes to comments. “There, I think the rule is sanctioned ignorance,” said Wood. And while he outlined a generalized pattern of how people react to a review that I felt fallacious, the difference between Wood and Mendelsohn is that the former was willing to give the format a chance and try to understand it, while the latter was happy to nuke the site from orbit like an uninformed cretin.

There were some notable differences between the two men about criticism. Wood pointed out that when reviews for his novel, The Book Against God, had come out, “I was relatively untouched by them.” He did, however, point out that he took it a bit personally when people read him wrong. He said, “I think you can’t be a critic unless you’re very, very curious,” although he suggested that he lacked that curiosity. He cited Alex Ross as a prime example of a good curious critic. He also observed, “If I’m a slightly sweeter critic than I used to be, it’s because I live with a novelist.”

Mendelsohn expressed reservations with the idea that critics are considered “a slightly lower level of life.” “I think it’s insulting if you’re worried about the feelings of the author. The feelings you should be worried about are in literature.” Wood responded to Mendelsohn, “I may feel it more acutely than you do, the hurt feelings of the author,” but he said, “In principle, this is not one’s concern.” But Wood did point to Mary McCarthy’s review of Dorothy Valcarcel’s The Man Who Loved Women, pointing out, “It’s so blithely disdainful in the end.” Weighing the review against Valcarcel’s agonies of producing this book offered a textbook example of what to consider as a critic. Wood also pointed to Hans Keller’s review of Anton Karas’s theme to The Third Man. Keller initially hated the theme, but found it hard to get out of his head. Keller declared, “As soon as I hate something, I ask myself why I like it so much.”

Mendelsohn noted that he only wrote about things that were interesting to him. “Critics write because they love their subject. They don’t care about people.” And yet despite “not caring,” he also pointed out, “I don’t think anyone wakes up in the morning and says, ‘I’m going to put one over on someone.'”

On the subject of literary posterity, Mendelsohn noted that one of Euripides’s well-received plays during his time, Orestes, isn’t read by anyone anymore, “except people like me.” Wood demonstrated slightly more insight into the subject by observing what Andrew Delbanco had observed in his Melville biography: There’s only one reference in the whole of Henry James to Melville, and that’s as a name on a list of Putnam writers.

Wood suggested that the present time was a ripe one for criticism, pointing out that there were numerous outlets for long-form criticism, that when Ian McEwan’s Saturday came out, there were a number of 3,000 to 4,000 word considerations of the novel. But he did not address recent newspaper cutbacks, nor did he consider how multiple reviews of the same book took away precious column inches from other books.

Close to the end of the conversation, Wood noted of the evening’s talk, “Here we have chats easily parodied by Monty Python.” He was also careful to point out that he was not in the best position to judge the state of reading because he was surrounded by literature grad students at Harvard who were excited about reading and writing. He attempted rather clumsily to offer a baseball metaphor, but won a few points from the audience for trying.

Regrettably, Iyer, who truly tiptoed more than he needed to, did not bring up a very important question for these two gentlemen: namely, their preferences for realism and modernism at the expense of genre and postmodernism. Iyer did allude that he had been waiting ten years to talk Pynchon with James Wood, but why didn’t he last night? DFW did come up, phrased through a clumsy question from the audience about whether the suicide represented a “literary gesture.” But the question’s poor framing prevented both critics from answering with any perspicacity.

The conversation suggested to me that Wood had more nuanced thoughts about criticism than Mendelsohn did, but that both men might be better served by expanding their repertoire.

As long as we remember (very, very important to remember) that a critic is merely a woman, or a man, presenting an *opinion*. And though there’s a distinction to be drawn between the educated opinion and its unschooled cousin, we’d do well to admit that Ludwig Wittgenstein (eg), for all that surging erudition, knew no more about Life (the totality, the generality or the private experience) than any other clear-eyed human with an open mind. So it goes with that other capital “L”, Literature.

Anyone craving the spiritual benefits (and cozy reassurances) of “authority” should steer clear of the Arts. Which is marvelous… unless you’re a mullah or a Mussolini.

Hi, I found your blog on this new directory of WordPress Blogs at blackhatbootcamp.com/listofwordpressblogs. I dont know how your blog came up, must have been a typo, i duno. Anyways, I just clicked it and here I am. Your blog looks good. Have a nice day. James.

I was also dumbfounded by Mendelsohn’s observation that nobody reads on subway trains anymore, and I also tested this claim on the R train and 6 train to work this morning. Conclusion: Daniel Mendelsohn must have been in a special train car for the blind when he made this observation, because the R train and 6 train were both absolutely packed with people reading newspapers, magazines and books this morning. From door to door I observed at least a hundred people reading.

Most likely, Mendelsohn never checked if people read on trains, but simply fabricated his observation out of thin air.

I enjoyed James Wood’s participation in this panel, but Daniel Mendelsohn’s insults towards bloggers were very off-putting. As a blogger sitting in the audience, I felt like one of the cavemen in a Geico commercial. And his insults towards bloggers weren’t even fresh — it was the same stuff Critical Mass was publishing week after week in 2006.

Good panel, but Daniel Mendelsohn needs to refresh his cultural coordinates.

“Should not the criticism itself be the thing that matters?”

Clearly it should. And ‘authority’ resides in the quality of said criticism.

“And ‘authority’ resides in the quality of said criticism.”

Critics (to one degree or another) would certainly love to think so. Loving to think so and *proving* it so are dauntingly different things, of course. Unless you’ve got an objective value or method of calibration for the word “quality” up your sleeve. Have you? Of course you haven’t. It’s the first hurdle and you’ve yet to clear it. Where’s the rigor, man?

Since there obviously hasn’t been a lot written about the blogs vs. print fuss before, I feel obligated to contribute.

We can all agree that the (intellectually) revolutionary/liberating potential of bogging lies in its ability to imitate Habermas’ pure public shpere, where individuals can discuss whatever with other individuals as individuals (as opposed to representatives/subjects of certain private or public institutions). The historical example Habermas gives of this phenomenon is the coffee-shop and pamphlet culture of Enlightenment England, where there were, of course, certain gender/class/etc restrictions to participation. But the discourse that went on was the very basis of our traditions of independent journalism, lay criticism and popular literature. The Internet of the present offers all the free-discourse potential with almost none of the restrictions. Participation in blogging itself is enough to justify your very participation, and quality is determined by the consensus of other bloggers (measured in site traffic, links, comments, etc). BUT, this pure public sphere is so constructed as to invariably collapse into itself, since when access is unrestricted, there is no quality-control mechanism, and “quality” is perpetually defined downward, so perfect communication breaks down and there is no consensual basis on which to judge quality. Tribalism/authoritarianism/anarchy are again poised to govern communication. (I think this has happened to blogs–don’t too many book bloggers spend most of their energy gently congratulating each other and circling the wagons against dissidents?) This very process is what has happened to our print culture, as it has been slowly swallowed by a few corporations and grown less diverse, less courageous, and less intelligent. Book-blogging, meanwhile, has seemed to operate from the start on the premise that it must imitate printed bookchat, with review-essays, author interviews, and reports of publishing news, gossip and whatever else(you know, the “hype cycle”). The quality of the journalism naturally varies from blog to blog (I have my favorites, like anybody else), but what hasn’t happened is an effort to really engage in literary criticism; that is, the thinking through of the technical, practical, and (yes) theoretical aspects of literature itself, as well as its institutions. Most bloggers apparently have inherited print-publishing’s rivalry with academic criticism, which has no doubt withered in the last few decades, but no doubt partly because of the parallel decline in quality of mainstream public discourse. A real uninhibited public sphere would take advantage of expertise (rather than mock it) and actually employ the insights of such discussion (a responsibility academic criticism has abdicated). The purpose of criticism should be the defense/advancement/challenging of literature itself (or politics, or culture: these newspaper-section divisions are just conventional, are they not?).

Any thoughts?

“Unless you’ve got an objective value or method of calibration for the word “quality” up your sleeve. Have you? Of course you haven’t. It’s the first hurdle and you’ve yet to clear it. Where’s the rigor, man?”

This is stale meat. I have already outlined criteria I consider useful in the evaluation of relative merit. Given your repeated denigration of such criteria, I can only assume that the Berlin Telephone Book would hold the same charm for you as say War and Peace or The Man Without Qualities.

Criticism is either good or bad. Its quality is determined by the rigor of its argument. Of course there is no right or wrong, but, as I’ve said before, if you want useful dialogue you have to agree on some kind of common ground.

I measure quality by comparing works under review against those I consider ‘great.’

You simply repeat the same old hapless relativism

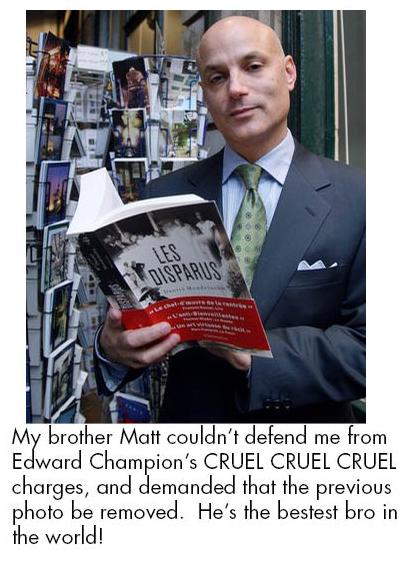

Edward:

Though I’m sure you will turn this into a brother-defending-a-brother thing (which it is, no doubt), please remove the my photo of Daniel that is currently posted on the site. As a professional photographer for the last 23 years, I take my copyright quite seriously. You can’t just pull a photo off the web and use it without permission, no matter how small the audience.

Thanks much,

Matt Mendelsohn

And here I thought Marion Ettlinger took the photo, but perhaps I was mistaking it for this?

For a man of words, that lame ass caption wouldn’t even get you an @Ed on Gawker.

Thanks for swapping my pilfered photo for another stolen one. I’d say it might help sales of Les Disparus in France but, well, you know.

Best,

Matt

Is what you observed on the subway really reading though? I mean, Better Homes and Gardens? Newsweek?

Ed,

You’ve always seemed to be so concerned about your own intellectual property rights(i.e. The license agreement of the Google browser, you’re Fletch post a few days back) that it seems quite hypocritical to make such snide remarks about someone else wanting to protect their own copyrights.

Matt Mendelsohn asked for the image to be removed. I removed it. His actions, by his own admission, are more motivated by his need to defend his brother rather than assert his copyright. That he chooses to troll here because both he and his brother are incapable of responding to the salient points of this post makes the Mendelsohns open to mockery in my book.

For me Ed, things like this are making it harder and harder to visit your site.

note: This is just a statement of fact, I’m not trying to incite any sort of fued, nor do I have any delusions that the loss of my traffic would in any way harm your life or your ability to live it happily. It’s simply reader feedback.

Okay. Hope you find the sanitized bloggers you’re looking for, Chris!

Nigel, you write:

“Criticism is either good or bad. Its quality is determined by the rigor of its argument. Of course there is no right or wrong, but, as I’ve said before, if you want useful dialogue you have to agree on some kind of common ground.”

The “useful dialogue” you pretend to want (when in fact, what you want is for everyone to accept your opinions on “good” and “bad” in Lit as higher truths) can be had by agreeing on the “common ground” of terms defined and limits recognized. People discuss religion and politics all the time without being able to agree on “good” or “bad”; the quality of the discussion depends on the ideas presented and the style of presentation, not on the possibility of a resolution (ie, X “good” and Y “bad).

Learn to face this reality in discussions of Art and it’ll represent a quantum leap in your ability to hold up your end of such a discussion. As it is, you can only “discuss” this issue with those with with whom you agree. The fact that you want absolutes in Art in order for *your* value judgments to be the Right Ones is not enough of an argument to make absolutes in Art possible.

Here’s how it goes:

There is no such thing as progress in the Arts. Any given contemporary audience of David Mamet’s or GBS’s or Harold Pinter’s cannot be said to have had a better experience of the playwright’s craft than an audience contemporary with Euripides had… despite the gap of a couple of millennia. The Arts change but they do not progress. Tastes change but they do not progress.

However, I can say with absolute certainty that Steven Hawking knows more about the universe than Isaac Newton did. That’s because science is more than well-argued opinion; science is a cumulative body of *knowledge*, built on a bulwark of measurable conditions/objective quantifications… there is the ongoing process of correction and counter-correction (zigs and zags and blind alleys in the path), but, still, we’ve come quite a distance since the days of Democritus, scientifically. Artistically, we haven’t come any distance, in real terms, from Shakespeare’s sonnets or Homer’s epics or the Mahabharata. None.

Art and Science are starkly distinct pursuits; you don’t seem to grasp that. You would affect to possess insights into Art without honoring it on its own terms. Any Art critic, underneath whatever baroque taxonomies or lambent cataracts of erudition, is merely discussing *feelings*: her/his feelings about an artifact; his/her guesses as to how the artifact works. The great Art critics can be Artists in their own right (ironically: by wandering so prodigally far from the work at hand that they cease being parasites and become Creators; James Wood is at his best when he’s furthest off the mark, in this respect) but they are not, in any proper sense of the word, adding to a body of knowledge. They are adding to the record of opinions. Taxonomy is not, by default, knowledge: anyone can name things, whether or not the things named exist, or relate in a way the names suggest.

This is a materialist age in which Art, in and of itself, is not seen as worthy; ergo your (reactionary) attempt to tart Art up in scientific drag and claim the glamour of scientific certainties. This is a sickness of the age.

The perception of Art is a matter of aesthetics and aesthetics are purely objective. I’d like to produce a definitive argument to the effect that *my* aesthetic is best (in objective terms) but it would be a fraudulent effort. Understanding this and moving on is a kind of wisdom. I don’t need to (and cannot) prove *your tastes* “wrong”, but I haven’t the patience to sit through any claims that there are (meaningful) objective evaluations possible in Art or Aesthetics.

James Wood (your apparent idol and master) argues his tastes beautifully; entertainingly, and so forth. It’s just too bad he has his heart so childishly set on being Right. At least he can take some consolation in the fact that he can’t be Wrong, either.

If asking you to remove a photograph of mine that you used without permission–especially given that I am, after all, a professional photographer–makes me a “troll” and “open to mockery,” well, then that says more, I think, about you than it does about me.

A troll is someone who lurks on message boards and makes stupid and inflammatory remarks. I wouldn’t exactly call one comment about copyright trollish, even if it’s true that I might not have noticed without the larger post about Daniel.

And if defending my brother against your snarky remarks is something to be mocked, well, so be it. That’s what siblings do. Maybe you’re an only child, who knows.

Chris (above) left an honest comment and you still responded with a sarcastic response. It seem to be a knee-jerk reaction with you–you might have a doctor look into that.

Matt: Again, because you haven’t responded to the claims within this post and wish to evade the issue, you’re a troll in my book. Between this and your brother’s preposterous claims that nobody reads in the subway, inter alia, you deserved to be mocked. This is the kind of out-of-touch entitlement that makes literature and literary criticism bad for everyone.

Steven & Nigel: Sweet Jesus. What do I have to do here to get you to kiss and make up?

Steven wrote:

“but I haven’t the patience to sit through any claims that there are (meaningful) objective evaluations possible in Art or Aesthetics.”

Well then go on your merry way, insulting learned critics, wasting time reading phone books and debating with those whose sole rejoinder is ‘beauty is in the eye of the beholder’, who refuse to accept that Robin Robertson’s poetry, for example, is more engaging than say, Rod McKuen’s; who refuse to entertain the possibility that one author, let’s go with Dostoevsky, has more to say, in more interesting, pleasing ways than another, say perhaps Nicholson Baker or Don Delillo.

Matt, let me give you some hard-earned advice (which, I suppose, I’m currently ignoring). Do not feed this organism. See Lev Grossman’s response to Ed’s vicious attacks in his Time magazine article for a better idea of how Ed operates–rather like a tapeworm, but feeding on attention rather than semi-digested food. Why does he do it? That is a question not just of psychiatry, but of moral philosophy–one I’m certainly not equipped to answer.

1. Erratum: “subjective” not “objective” (first line, penultimate paragraph).

2. Ed: worry not, I’ll lay off. You’ve got your hands full with the Brothers Mendelsohn. Apropos of which: I sure miss the days when Gore Vidal was trolling William F. Buckley (and vice versa)… infinitely less civil.

Ed: Do continue to believe that spotting people with copies of Newsweek and Home & Gardens is probably not “reading” as JW and DM would define it. Not to speak for them. It just doesn’t seem like cause for celebration, that middle-brow parade you witnessed.

I’ve got to go along with Chris on this. You made some good points in your post, but slagging Matt Mendelsohn doesn’t help make your case. Doesn’t hurt it, either–it’s just irrelevant and unpleasant.

“Newsweek” and “Home & Gardens” don’t count as reading? Ridiculous!

Today I saw people reading Ian McEwan and Wally Lamb on the subway, not that it matters what they’re reading.

Okay, so after a few days of mulling this over….

After a few months away from the blogosphere I cannot believe the Ed/Matt/Daniel arguments still rage. Jesus, guys, can’t you let up? I mean, take a look around. Rome is burning.

More importantly, if we can all take a half step back, bloggers and print devotees who love serious reading–or those of us who adore both–must admit that print publishing is in trouble. …so, um, shouldn’t book lovers band together? I realize I sound like Rodney King by way of Berkeley in 1967, but good writing can appear anywhere….as can really shitty writing. And passionate readers (and I am not talking Danielle Steel devotees) can tell the difference. Is good criticism enlightening? Sure. Are we all reduced to Terre Haute idiots without it? Nope. That said, I doubt Mr. Mendelsohn will be filing for unemployment any time soon. Nor, hopefully, will Ed.

Diane Leach, I second your attempt at peacemaking, but I disagree with your basic premise. I can’t speak for Ed (though I have had conversations with him about this and I think he may agree with me here) but I think many book lovers are skeptical about the idea that the book business is in trouble. It’s actually the careers of many unsuccessful corporate publishing executives that are in trouble (read Boris’s piece in New York magazine between the lines, and this is what emerges). Book publishing remains a $30 billion/year business. It is comparable in size to the film industry and the music industry. All three of these industries are going through difficult changes, but this is because the main corporate players in these fields are having trouble matching their profit goals while adjusting to the pricing changes of an internet-based arts/entertainment scene.

So, no, I don’t agree that print publishing is in trouble, just because Random House and Simon & Schuster are in trouble. Reading remains incredibly popular and widespread. And again … it’s a $30 billion/year business. That’s the kind of trouble a lot of industries would love to be in.

According to Peter Robins’ blog at the Telegraph, Infinite Jest got a 600-word review in the T when it first came out. If the blogosphere had been in something like its present state, IJ wouldn’t have had to fight it out with rivals for column inches – and, of course, readers would have had a better chance of seeing more substantial reviews in periodicals to which they weren’t subscribers.

I’m wondering how much one can tell from the reading habits of commuters in transit. I sometimes take my iPod to the gym; I listen to all sorts of things, but I can’t imagine playing Tannhäuser or Beethoven’s Ninth. If I’m on the subway I’m likelier to read the FT than, I don’t know, my OCT of Antigone. I can imagine reading DFW’s Oblivion on the subway, but Wyatt Mason found it difficult; it’s reasonable to suppose that quite a lot of people wouldn’t have found it a good choice for reading en route from A to B.

I can’t say that I, in my mid-twenties, have much ability to recall the days when the populace slogged through Henry James and Wallace Stevens on subways, trams, and crank-ferries, but I wonder if such a discussion is even worth having. A crowded subway isn’t really the sort of environment in which I enjoy anything other than a newspaper. Usually I stare out the window.

I should point out that while Mendelsohn’s comment is, perhaps, flawed in its universality (his word choice implies that no one, anywhere, ever sees anyone reading anything “meaningful” on a train), he is partially correct. I can say that many people my age don’t read on subways, electing instead to fool around on their cell phones, or get a head start on (or wrap up) items that cropped up during the day during work. Some of them don’t read on or off public transit: I know a recent college graduate who only buys audiobooks. (Not because he’s always in a car, but because he simply doesn’t read. Period.) This may reflect a larger trend in the lives of young professionals, but it certainly doesn’t only encompass reading habits. Anyway, after ten or twelve hours spent in front of a computer screen, reading documents, or whatever else a person’s job entails, forty minutes of letting one’s mind wander is not unappealing. How, exactly, one accomplishes that doesn’t seem fodder for critical interpretation unless lit crits are also anthropologists.

[…] if people aren’t reading on the subway, then surely they can’t be reading in blue-collar Latino neighborhoods either! Daniel […]

Mr. Champion, I just discovered your blog looking for more about the Mendelsohn-Wood talk. At first I was excited to find a seemingly smart blog. But your comments to Matt Mendelsohn assure me that you’re a self-aggrandizing dunce. The man always has the right to assert copyright if he’s the copyright holder. Moreover, he has no duty to defend his brother against your creepy blog post (a woman unbuttoned her blouse in response to your scrawling? please). The fact that you were so wounded by his request and his choice not to dignify your rants — and that you responded so childishly — does indeed say volumes about you. Unfortunate.

I assure you, Mr. Roque, a coward who cannot be bothered to leave his real name, that there is no intellectual value to this blog whatsoever, and that it is often unapologetically childish. Unlike you, I am a grown man who actually enjoys life, whether the experience is more common to a six-year-old or a 66-year-old. If reporting the truth, however unsavory to you, is “self-aggrandizing,” then this says more about your myopic, sheltered, and humorless existence than it does about my stance here, which I have always been true about.