[NOTE: Earlier this year, I was commissioned to write a review of Mary Otis’s Yes, Yes, Cherries. Regrettably, the piece had to be killed, due to lack of space. Since enough time has passed for its legitimate reproduction and it’s too late to find a home for this piece, I feature it here on these pages.]

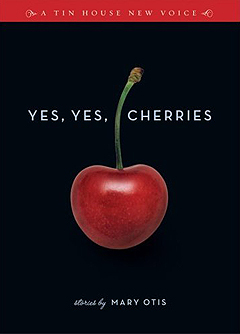

Yes, Yes, Cherries

(Tin House Books, 210 pp., $12.95)

“Society often forgives the criminal; it never forgives the dreamer.” — Oscar Wilde, “The Critic as Artist”

The ten tales told in Yes, Yes, Cherries, Mary Otis’s debut short story collection, chart the existential snags and crags familiar to all dreamers. Otis plots an unforgiving but readily identifiable topography. Libraries are sanctuaries, but sometimes snares. Doctors offer prescriptions, but only after they’ve pumped clients for details about their sex lives. DDSes may be “gentle dental folk,” but the uprooted wisdom teeth leave crestfallen cavities.

Otis’s work resides somewhere between Aimee Bender’s behavioral examination and Lorrie Moore’s mordant worldview. She has a great talent for pinpointing external perception’s slings and arrows on the insular fantasist. In “Five-Minute Hearts,” a bookstore clerk named Brenda attends a party with her new boyfriend. The car breaks down on the way and, when a trucker pulls over to assist, Brenda reimagines this long-haired do-gooder and her boyfriend’s daughter as a family portrait for “the Lexus-load of businessmen passing at this instant.” All this occurs shortly after Brenda’s boyfriend insists that she’s not his wife. It’s a troubling disparity also surveyed in “The Next Door Girl,” in which a Bakersfield émigré remarks that “exuberance had not been a thing to aspire to” in her hometown. In “Stones,” a woman recalls “an instance when Phil ridiculed her for not knowing that pesto sauce should never be heated.” Even one’s beverage decisions can’t escape harsh pronouncements. In “Triage,” a mother tells her daughter, “Tea is a nervous person’s drink.”

Otis’s work resides somewhere between Aimee Bender’s behavioral examination and Lorrie Moore’s mordant worldview. She has a great talent for pinpointing external perception’s slings and arrows on the insular fantasist. In “Five-Minute Hearts,” a bookstore clerk named Brenda attends a party with her new boyfriend. The car breaks down on the way and, when a trucker pulls over to assist, Brenda reimagines this long-haired do-gooder and her boyfriend’s daughter as a family portrait for “the Lexus-load of businessmen passing at this instant.” All this occurs shortly after Brenda’s boyfriend insists that she’s not his wife. It’s a troubling disparity also surveyed in “The Next Door Girl,” in which a Bakersfield émigré remarks that “exuberance had not been a thing to aspire to” in her hometown. In “Stones,” a woman recalls “an instance when Phil ridiculed her for not knowing that pesto sauce should never be heated.” Even one’s beverage decisions can’t escape harsh pronouncements. In “Triage,” a mother tells her daughter, “Tea is a nervous person’s drink.”

Otis’s adult characters often find escape from such assaults by dwelling upon childhood. When Allison’s husband asks her about her layoff, “the Tilt-a-Whirl of her heart slows and lowers, slows and lowers, thwacking to a stop.” A flight attendant in “Triage” is named Lonnie Childs. Childhood, however, is hardly an escape route. Her children shriek for candy at inopportune moments or, as in “The Straight and Narrow,” canvass mothers to start a “Standard American Diet.”

One of Otis’s misfits, Allison, appears in four stories and truly puts the Mitty into mitigating. The first half of this quirky quartet, “Pilgrim Girl” and “Welcome to Yosemite,” are pitch-perfect, depicting Allison’s adolescent seduction by an insurance man and, years later, her life as an elementary school teacher. These two tales crackle because Otis understands the rocky relationship between conformity and personal imagination. The young Allison is first observed impersonating a saleswoman, forced by her mother to “get out of herself.” Later, we learn that Allison does not wear underwear to class, but that her audacious sartorial choice is not the reason she loses her job. She’s canned because a trusted teaching assistant has offered a sworn statement reading, “Allison seems greatly distracted, in general.”

Unfortunately, in the next two stories, Otis abandons this balance for a more pedestrian nervous breakdown. In “Stones,” Allison is asked by a therapist to “visualize herself on an ice floe in the middle of the ocean.” While this is an interesting observation on how institutional thinking encroaches upon personal identity, it leaves little room for Allison’s imagination to assert itself.

But Otis’s delightful comparisons atone for these lapses in character development. A disloyal husband “travels through life like a midsize rental car.” An actress’s ample décolletage is like a “soft velvety crack in [a] sofa.” Otis is also preoccupied with machines as a remedy for societal ills, such as the “contraption,” an exercise unit in “Welcome to Yosemite” designed to strengthen hearts.

One must also applaud a writer whose filigree is fingers and chicken. Fingers are frequently described, their sizes and motions intruding upon Otis’s narratives like invasive tendrils. Indeed, in “Stones,” Allison consults “a guide that shows how to become more confident through the repeated practice of certain hand gestures.” The smell of chicken is a troubling presence in two tales, and in “The Next Door Girl,” Tender Chickens crops up as “an extraweird sex magazine.” Otis’s prose isn’t particularly concerned with pronouns. She’s more content to drive declarative sentences through first names, eschewing “he” and “she” (and particularly “they”) whenever possible, perhaps because dreaming is contingent on personal identity.

Otis is also taken with cockeyed quips (“Honey, where’s the rake?” reads one double entendre), but she sometimes relies on rudimentary declarations that lack the fizzle of her dialectic between society and imagination. “The air at Nordstrom’s has a fine ingredient,” says a father in “Picture Head,” who constantly compares his surroundings to his early life working on a tanker. In the title story, a digression on a Revolutionary War quiz featured on a menu hinders a promising narrative initiated by borderline nymphomania. That’s too bad. Otis’s voice is too interesting to dwell upon commonplace consumerism.

But these are pedantic quibbles for a promising writer who successfully convinces that the dreamers are as worthy of pardon as the criminals.

[UPDATE: Rodney Welch was likewise inspired to post his killed review of T.R. Pearson’s Glad News of the Natural World. Hopefully, this new practice will set a trend of killed reviews being reposted in their entirety online. (Which makes me wonder just how many reviews have been killed over the past year.) Dan Green has additional thoughts on the subject.]

“DDSes may be “gentle dental folk,” but the uprooted wisdom teeth leave crestfallen cavities.”

“She has a great talent for pinpointing external perception’s slings and arrows on the insular fantasist.”

Maybe your piece was killed because the prose is prissy and unreadable.

I love this collection- very reminscent of Mary Gaitskill in that Otis has the ability to get inside the head of that person who lives on the periphery.

To Derek above:

Did you actually try to read the book or did you base your snarky comment on the few quotes posted here? I suggest you do the author the justice of reading before gabbing. The book is a gem.

To Orchide:

I’m not talking about the book’s prose. I’m talking about Ed’s.