There are people who have seriously wronged me and I have said nothing. I don’t give them a whit of my thoughts and I do everything in my power to avoid running into them, even as I leave the door open for reconciliation if they want to approach me and seek amends. That is the least we can do as human beings. It is a focus that took me five years to figure out. And I’m a lot happier and more creative as a result.

But every now and then, you find out about someone who is still unhealthily fixated on you. There is someone online who has been obsessed with me now for a good nine years. Nine years. It’s almost as if she thinks we were married or something, but I’ve never met her and I’ve had a grand total of two interactions with her.

Even so, I would rather be honest about my inadequacies rather than bask in the sham panacea of feeling better about myself. The truth of the matter is that, while I have made great strides in finding more compassion for people, I am clearly not extending enough unconditional empathy in my life. Rather than holding grudges, I simply erase people who have hurt me from my existence. I do this because to dwell on them further is to invite more anger I don’t need into my life. I view this as a great moral failure and I am hoping to make greater strides in being more understanding towards other perspectives. Some may argue that there is nothing wrong with avoiding toxic people and there is certainly some truth to this. You don’t want to surround yourself with people who belittle you. On the other hand, the definition of “toxic” has become highly malleable in recent years. We are more content to write someone off over a minor disagreement in opinion rather than an assiduous assessment of what our actual relationship is and could be with another person.

The person who is obsessed with me doesn’t seem to be happy. I keep waiting for her to stop being obsessed with me. For goodness sake, when do you let something go? It’s clear from an objective analysis that she hasn’t done much with her life and that she has creative aspirations that she hasn’t tried to pursue (or, if she has, it didn’t go as planned; Ed, you’ve been there; so what’s with the paralysis?). So I suspect that’s one of the reasons she’s projecting her wanton fury onto me. She keeps publicly comparing me to the likes of Bill Cosby, Alan Dershowitz, and other terrible people with whom I clearly share no qualities. My response has been to stay resolutely silent and keep her blocked on all social media. I suppose she’s the Annie Wilkes to my Paul Sheldon. I suppose that I should count myself fortunate that I haven’t been in a car accident in her neighborhood.

I really don’t comprehend this kind of obsessive jealousy. But if you’re actively busting your hump on the creative front and being transparent about your process to provide help and inspiration to others, it is an inevitable and unfortunate reality. Hate and jealousy tends to bubble up from people who aren’t doing anything with their lives. We rarely talk of thwarted ambitions and the way in which people project their own failures onto others rather than taking the time to see how they can make their lives happen. The jealous grudgeholder looks at some figure who is actively seizing the reins with originality, good will, and a solid work ethic and perceives weird opportunities to resent the target and tear him down. This is to be distinguished from reasonable criticism, which allows an audience to thoughtfully comprehend another person’s work and is often quite useful, but should never be taken personally.

I suppose I’m thinking about this person because there is a part of me who wants to empathize with her crazed zeal and redress this weird grievance she has with me, even as I simultaneously recognize that doing so may not be good for my wellbeing and will probably not result in anything more than further grief on my end and renewed obsession from her. There’s also the question of whether I have the emotional energy to fully empathize with her position and provide the appropriate closure for both of us. Dylan Morran has a podcast called Conversations with People Who Hate Me in which he talks with people who have made him the object of their anger. Even though I greatly commend his efforts to reach out to his enemies, I still think that Morran isn’t being entirely transparent about the selective manner in which he practices his professed empathy. Because that’s the thing. Empathy isn’t just about listening to your enemy. It’s about finding the visceral space inside you to truly feel and understand your enemy’s perspective. You can’t extend an olive branch through a pro forma gesture. You really have to demonstrate that you genuinely care.

The excellent British TV series, Back to Life, written by Daisy Haggard and Laura Solon, is one of the few recent offerings that deals with the double-edged sword of trying to empathize with someone who has committed a monstrous act. Miri Matteson (played by Haggard) has served an eighteen year prison sentence for murdering one of her best friends and returns to her small town in Kent to rebuild her life and find a second chance. The show is brilliant in the way that it doesn’t dwell specifically on Miri’s crime, but rather Miri’s life as it is now. The town vandalizes her parents’ home, where she is staying. She manages to land a job at a fish and chips place gentrifying the neighborhood (a beautifully subtle metaphor for the need to accept change), but a brick is thrown through the window during one of her shifts.

All this leaves the audience contending with a vital moral question. Does anyone deserve such treatment? If a transgressor has done her time and is peacefully trying to forge a stable life, shouldn’t we grant the transgressor that opportunity? The show counterbalances Miri’s struggles to readjust with benevolent gestures from a neighbor who is unfamiliar with Miri’s past, but who accepts Miri on her own terms, even going to the trouble of fixing her childhood swing in the dead of night and extending decency. The show suggests, through humor and a nimble attentiveness to behavior, that there is a certain human strength that emerges from simply accepting someone on their own present terms. Moreover, as the truth of Miri’s past becomes more dominantly recognized in the present, we are forced to consider the question of how prohibiting a transgressor from having a second chance may cause the transgressor to repeat the old patterns. Sure, nobody owes anyone a second chance. But what great possibilities and connections are we denying by insisting that someone’s transgressive nature is permanent? The idea of not giving a transgressor a second chance used to be a conservative staple, but now it has become increasingly practiced by ostensible liberals.

The criminologist John Braithwaite has written a number of very useful volumes on restorative justice — particularly, Crime, Shame, and Reintegration, in which he points to many statistics where disintegrative shaming — meaning the permanent stigmatization of someone who has transgressed — often leads to recidivism. Whereas reintegrative shaming, meaning a period of shaming followed by forgiveness and a slow acceptance of the transgressor back into a community (rather than making him an outcast), usually results in greater peace. Among Braithwaite’s many examples is the fact that American offenders are more than twenty times as likely to be incarcerated as Japanese offenders. The difference is that Japan takes on the shame as a collective community rather than passing the shame onto the individual.

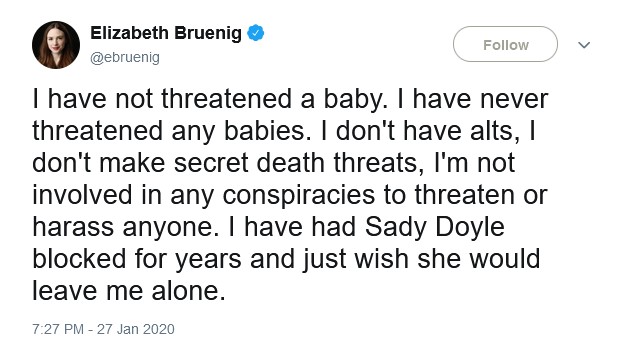

So if reintegration works better than shaming, why then can I not find it within me to settle the dispute with the person who is obsessed with me? Obviously, Braithwaite, writing in 1989, could not anticipate the rise of social media weaponized to destroy lives and careers. He could not anticipate how instant spurts of 280 character tweets result in people forming cartoonish impressions about people, such as Sady Doyle falsely accusing opinion writer Liz Bruenig last week of threats without producing a shred of evidence. What rational person can blame Bruenig for her response? Most people, faced with the mania of impressions and accusations, just want to be left alone. (The above screenshot is from a tweet that Bruenig deleted. To offer full disclosure, Doyle has also lied about and libeled me, as well as some of my friends. But I also understand from people who know her that she is suffering from mental health problems. My hope for her, despite the hurt she caused me and the translucent relish she took in meting it out, is that people close to her can get her the help and the treatment she clearly needs so that she doesn’t have to behave like this again.)

Even when we talk about the need for more empathy, you can’t escape the fact that it will always be selectively and individually applied. I’m willing to own up to my own flaws on this front. But the people who have advanced careers through this philosophical position don’t seem to have the same ability. After all, they have books to sell rather than hearts to extend. Five years ago, Jon Ronson wrote a book called So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed?. While Ronson’s volume was certainly progressive in the way that it asked us to consider the lives of people who had been hounded by the hordes, the problem with Ronson is that he can only perceive disproportionate punishment with “people who did virtually nothing wrong.” I’ve read and listened to a lot of Ronson interviews and I’ve yet to find a case where he has shown willingness to extend true empathy to people who have done something wrong and who want to make their lives better. The whole point of justice is to allow for rehabilitation and reintegration. While Ronson demonstrated how perceived transgressors suffered undue hardship, you can’t even begin to have a conversation like this until you consider how people who have been “canceled” live out their lives. Nobody’s life ends just because you decided to wipe him away from your windshield.

Perhaps we do have some collective obligation to reach out when it’s difficult. I recently settled a dispute with someone who had falsely and belligerently accused me of behavior that I never committed in a support group. Instead of getting angry with him, I took a deep breath and wrote a very careful message with him pointing out that I understood his feelings and that I had been carefully listening to him the entire time while also declaring that I genuinely cared for him and refused to feel angry towards him. He then sent a message to me apologizing for his previous message and declaring me a “good guy.” We were able to patch it up, but that’s only because we had actually met face to face and had taken a little bit of time to know each other.

Social media, despite its professed “social” qualities, doesn’t allow us that pivotal face-to-face contact. It doesn’t allow us to better understand another person’s motivations and perspective and find common points of empathy. It is a common truth that most disputes can be settled easily in person. But we have increasingly shifted to an age in which people pine for the easier method of erasing someone from existence. It is far easier to stigmatize someone if we have never gone to the trouble to know them. But it also reduces complex human beings into little more than one-dimensional transactional vessels. One can look no further than the rise of ghosting and people writing others off on flimsy pretext if you have the misfortune of being single in the metropolitan New York area.

The question we now face is whether reintegration as a virtue for a better and happier world that allows more people opportunities to live positive lives overshadowing their worst mistakes is something that we can implement in an age driven by castigatory social media. It’s certainly a tough sell. But I also recognize that, as more data about individuals becomes increasingly public and more past episodes are dredged into the bright xenon lights of public opinion, we’re going to need to find more ways of embracing this necessary difficulty. It isn’t feasible to ask anyone to live up to an impossible virtue. But there is always something very beautiful in learning how to empathize with someone once we have come to understand why they committed their worst mistakes and once we see that they, like us, are willing to change.