(This is the twenty-second entry in The Modern Library Nonfiction Challenge, an ambitious project to read and write about the Modern Library Nonfiction books from #100 to #1. There is also The Modern Library Reading Challenge, a fiction-based counterpart to this list. Previous entry: The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt.)

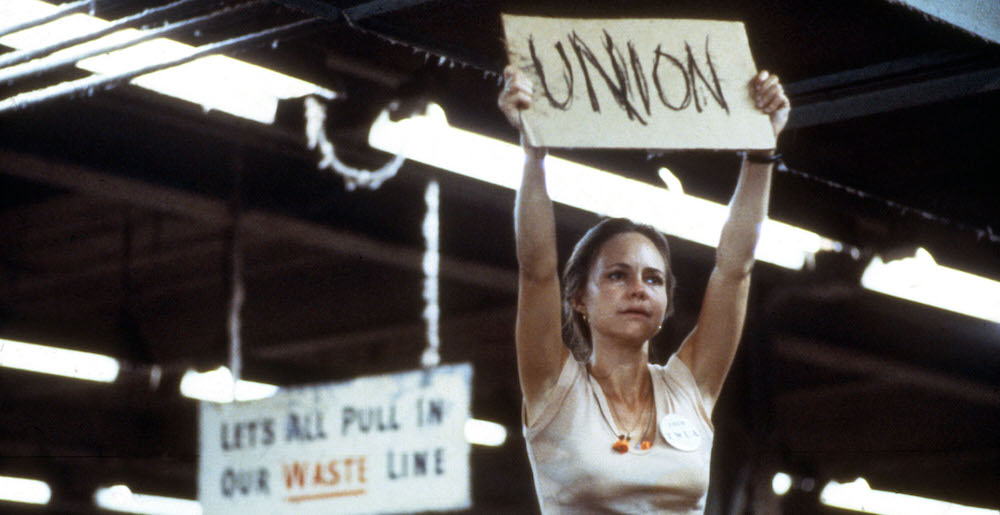

It was a warm day in April when Dr. Martin Luther King was arrested. It was the thirteenth and the most important arrest of his life. King, wearing denim work pants and a gray fatigue shirt, was manacled along with fifty others that afternoon, joining close to a thousand more who had bravely submitted their bodies over many weeks to make a vital point about racial inequality and the unquestionable inhumanity of segregation.

It was a warm day in April when Dr. Martin Luther King was arrested. It was the thirteenth and the most important arrest of his life. King, wearing denim work pants and a gray fatigue shirt, was manacled along with fifty others that afternoon, joining close to a thousand more who had bravely submitted their bodies over many weeks to make a vital point about racial inequality and the unquestionable inhumanity of segregation.

The brave people of Birmingham had tried so many times before. They had attempted peaceful negotiation with a city that had closed sixty public parks rather than uphold the federal desegregation law. They had talked with businesses that had debased black people by denying them restaurant service and asking them to walk through doors labeled COLORED. Some of these atavistic signs had been removed, only for the placards to be returned to the windows once the businesses believed that their hollow gestures had been fulfilled. And so it became necessary to push harder — peacefully, but harder. The Birmingham police unleashed attack dogs on children and doused peaceful protesters with high-pressure water hoses and seemed hell-bent on debasing and arresting the growing throngs who stood up and said, without raising a fist and always believing in hope and often singing songs, “Enough. No more.”

There were many local leaders who claimed that they stood for the righteous, but who turned against King. White leaders in Birmingham believed — not unlike pro-segregation Governor George Wallace just three months earlier — that King’s nonviolent protests against segregation would incite a torrent of violence. But the violence never came from King’s well-trained camp and had actually emerged from the savage police force upholding an unjust law. King had been very careful with his activists, asking them to sign a ten-point Commitment Card that included these two vital points:

6. OBSERVE with both friend and foe the ordinary rules of courtesy.

8. REFRAIN from the violence of fist, tongue, or heart.

Two days before King’s arrest, Bull Connor, the racist Birmingham Commissioner of Public Safety and a man so vile and heartless that he’d once egged on Klansmen to beat Freedom Riders to a pulp for fifteen minutes as the police stood adjacent and did not intervene, had issued an injunction against the protests. He raised the bail bond from $200 to $1,500 for those who were arrested. (That’s $10,000 in 2019 dollars. When you consider the lower pay and the denied economic opportunities for Birmingham blacks, you can very well imagine what a cruel and needless punishment this was for many protesters who lived paycheck to paycheck.)

And so on Good Friday, it became necessary for King, along with his invaluable fellow leaders Ralph Abernathy and Fred Shuttlesworth, to walk directly to Birmingham Jail and sing “We Shall Overcome.” King took a very big risk in doing so. But he needed to set an example for civil disobedience. He needed to show that he was not immune to the sacrifices of this very important fight. The bondsman who provided the bail for the demonstrators told King that he was out as King pondered the nearly diminished funds for the campaign. In jail, King would not be able to use his contacts and raise the money that would keep his campaign going. Despite all this, and this is probably one of the key takeaways from this remarkable episode in political history, King was dedicated to practicing what he preached. As he put it:

How could my failure now to submit to arrest be explained to the local community? What would be the verdict of the country about a man who had encouraged hundreds of people to make a stunning and then excused himself?

Many who watched this noble march, the details of which are documented in S. Jonathan Bass’s excellent book Blessed Are the Peacemakers, dressed in their Sunday best out of respect for King’s efforts. Police crept along with the marchers before Connor gave the final order. Shuttlesworth had left earlier. King, Abernathy, and their fellow protestors were soon surrounded by paddy wagons and motorcycles and a three-wheel motorcart. They dropped to their knees in peaceful prayer. The head of the patrol squeezed the back of King’s belt and escorted him into a police car. The police gripped the back of Abernathy’s shirt and steered him into a van.

King was placed in an isolation cell. Thankfully, he did not suffer physical brutality, but the atmosphere was dank enough to diminish a weaker man’s hope. As he wrote, “You will never know the meaning of utter darkness until you have lain in such a dungeon, knowing that sunlight is streaming overhead and still seeing only darkness below.” Jail officials refused a private meeting between King and his attorney. Wyatt Tee Walker, King’s chief of staff, sent a telegram to President Kennedy. The police did not permit King to speak to anyone for at least twenty-four hours.

As his confidantes gradually gained permission to speak to King, King became aware of a statement published by eight white clergy members in Birmingham — available here. This octet not only urged the black community to withdraw support for these demonstrations, but risibly suggested that King’s campaign was “unwise and untimely” and could be settled by the courts. They completely missed the point of what King was determined to accomplish.

King began drafting a response, scribbling around the margins of a newspaper. Abernathy asked King if the police had given him anything to write on. “No,” King replied, “I’m using toilet paper.” Within a week, he had paper and a notepad. King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” contained in his incredibly inspiring book Why We Can’t Wait, is one of the most powerful statements ever written about civil rights. It nimbly argues for the need to take direct action rather than wait for injustice to be rectified. It remains an essential text for anyone who professes to champion humanity and dignity.

King’s “Letter” against the eight clergymen could just as easily apply to many “well-meaning” liberals today. He expertly fillets the white clergy for their lack of concern, pointing out that “the superficial kind of social analysis that deal with effects and does not grapple with underlying causes.” He points out that direct action is, in and of itself, a form of negotiation. The only way that an issue becomes lodged in the national conversation is when it becomes dramatized. King advocates a “constructive, nonviolent tension that is necessary for growth” — something that seems increasingly difficult for people on social media to understand as they block viewpoints that they vaguely disagree with and cower behind filter bubbles. He is also adamantly, and rightly, committed to not allowing anyone’s timetable to get in the way of fighting a national cancer that had then ignobly endured for 340 years. He distinguishes between the just and the unjust law, pointing out that “one has a moral responsibility to obey unjust laws.” But he is very careful and very clear about his definitions:

An unjust law is a code that a numerical or power majority group compels a minority group to obey but does not make binding on itself. This is difference made legal. By the same token, a just law is a code that a majority compels a minority to follow and that it is willing to follow itself. This is sameness made legal.

This is a cogent philosophy applicable to many ills beyond racism. This is radicalism in all of its beauty. This is precisely what made Martin Luther King one of the greatest Americans who ever lived. For me, Martin Luther King remains a true hero, a model for justice, humility, peace, moral responsibility, organizational acumen, progress, and doing what’s right. But it also made King dangerous enough for James Earl Ray, a staunch Wallace supporter, to assassinate him on April 4, 1968. (Incidentally, King’s family have supported Ray’s efforts to prove his innocence.)

Why We Can’t Wait‘s scope isn’t just limited to Birmingham. The book doesn’t hesitate to cover a vast historical trajectory that somehow stumps for action in 1963 and in 2019. It reminds us that much of what King was fighting for must remain at the forefront of today’s progressive politics, but also must involve a government that acts on behalf of the people: “There is a right and a wrong side in this conflict and the government does not belong the middle.” Unfortunately, the government has doggedly sided against human rights and against the majestic democracy of voting. While Jim Crow has thankfully been abolished, the recent battle to restore the Voting Rights Act of 1965, gutted by the Supreme Court in 2013, shows that systemic racism remains very much alive and that the courts for which the eight white Birmingham clergy professed such faith and fealty are stacked against African-Americans. (A 2018 Harvard study discovered that counties freed from federal oversight saw a dramatic drop in minority voter turnout.)

Much as the end of physical slavery inspired racists to conjure up segregation as a new method of diminishing African-Americans, so too do we see such cavalier and dehumanizing “innovations” in present day racism. Police shootings and hate crimes are all driven by the same repugnant violence that King devoted his life to defeating.

The economic parallels between 1963 and 2019 are also distressingly acute. In Why We Can’t Wait, King noted that there were “two and one-half times as many jobless Negros as whites in 1963, and their median income was half that of the white man.” Fifty-six years later, the Bureau of Labor Statistics informs us that African Americans are nearly twice as unemployed as whites in a flush economic time with a low unemployment rate, with the U.S. Census Bureau reporting that the median household income for African-Americans in 2017 was $40,258 compared to $68,145 for whites. In other words, a black family now only makes 59% of the median income earned by a white family.

If these statistics are supposed to represent “progress,” then it’s clear that we’re still making the mistake of waiting. These are appalling and unacceptable baby steps towards the very necessary racial equality that King called for. White Americans continue to ignore these statistics and the putatively liberal politicians who profess to stand for fairness continue to demonstrate how tone-deaf they are to feral wrongs that affect real lives. As Ashley Williams learned in February 2016, white Democrats continue to dismiss anyone who challenges them on their disgraceful legacy of incarcerating people of color. The protester is “rude,” “not appropriate,” or is, in a particularly loaded gerund, “trespassing.” “Maybe you can listen to what I have to say” was Hillary Clinton’s response to Williams, to which one rightfully replies in the name of moral justice, “Hillary, maybe you’re the one here who needs to listen.”

Even Kamala Harris, now running for President, has tried to paint herself as a “progressive prosecutor,” when her record reveals clear support for measures that actively harm the lives of black people. In 2015, Harris opposed a bill that demanded greater probing into police officer shootings. That same year, she refused to support body cams, only to volte-face with egregious opportunism just ten days before announcing her candidacy. In the case of George Gage, Harris held back key exculpatory evidence that might have freed a man who did not have criminal record. Gage was forced to represent himself in court and is now serving a 70-year sentence. In upholding these savage inequities, I don’t think it’s a stretch to out Kamala Harris as a disingenuous fraud. Like many Democrats who pay mere lip service to policies that uproot lives, she is not a true friend to African Americans, much less humanity. It was a hardly a surprise when Black Lives Matter’s Johnetta Elzie declared that she was “not excited” about Harris’s candidacy back in January. After rereading King and being reminded of the evils of casual complicity, I can honestly say that, as someone who lives in a neighborhood where the police dole out regular injustices to African-Americans, I’m not incredibly thrilled about Harris either.

But what we do have in this present age is the ability to mobilize and fight, to march in the streets until our nation’s gravest ills become ubiquitously publicized, something that can no longer be ignored. What we have today is the power to vote and to not settle for any candidate who refuses to heed the realities that are presently eating our nation away from the inside. If such efforts fail or the futility of protesting makes one despondent, one can still turn to King for inspiration. King sees the upside in a failure, galvanizing the reader without ever sounding like a Pollyanna. Pointing to the 1962 sit-ins in Albany, Georgia, King observes that, while restaurants remained segregated after months of protest, the activism did result in more African-Americans voting and Georgia at long last electing “the first governor [who] pledged to respect and enforce the law equally.”

It’s sometimes difficult to summon hope when the political clime presently seems so intransigent, but I was surprised to find myself incredibly optimistic and fired up after rereading Why We Can’t Wait for the first time in more than two decades. This remarkable book from a rightfully towering figure seems to have answered every argument that milquetoasts produce against radicalism. No, we can’t wait. We shouldn’t wait. We must act today.

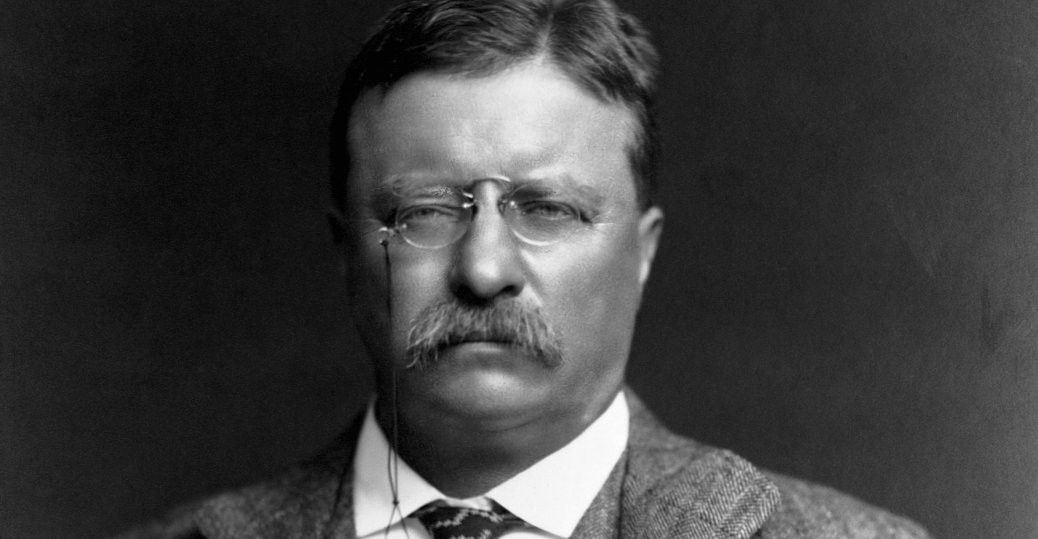

One of many blistering tangerines contained within Mark Twain’s juicy three volume Autobiography involves his observations on Theodore Roosevelt: “We have never had a President before who was destitute of self-respect and of respect for his high office; we have had no President before who was not a gentleman; we have had no President before who was intended for a butcher, a dive-keeper or a bully, and missed his mission of compulsion of circumstances over which he had no control.”

One of many blistering tangerines contained within Mark Twain’s juicy three volume Autobiography involves his observations on Theodore Roosevelt: “We have never had a President before who was destitute of self-respect and of respect for his high office; we have had no President before who was not a gentleman; we have had no President before who was intended for a butcher, a dive-keeper or a bully, and missed his mission of compulsion of circumstances over which he had no control.”

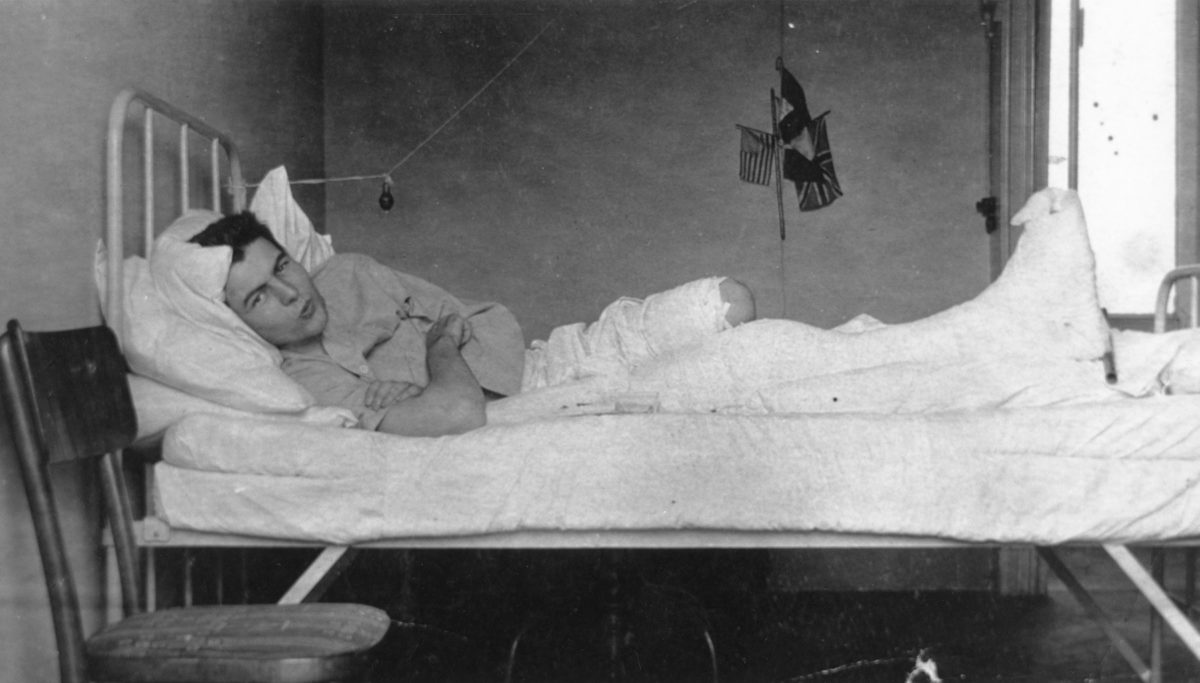

You likely know the basics: An American goes to Italy and enlists as a “tenente.” He drives a battlefield ambulance just before his nation enters World War I. He gets wounded. He meets a nurse at a hospital. He falls in love. He feels free as he recovers. He feels trapped as he returns to the front. He gets disillusioned. He flees. He finds her again. Bad things happen. But A Farewell to Arms is so much more than this. It is a heartbreaking love story. It is a remarkably subtle indictment of war. It shows how people bury their romantic longings behind duty and how there’s a greater bravery in fulfilling what you owe to your heart. It argues for life and love. Its final paragraph is devastating. It zooms along with masterly prose that is buried with treasure. It is one of the greatest novels of the early 20th century. This statement is not hyperbole.

You likely know the basics: An American goes to Italy and enlists as a “tenente.” He drives a battlefield ambulance just before his nation enters World War I. He gets wounded. He meets a nurse at a hospital. He falls in love. He feels free as he recovers. He feels trapped as he returns to the front. He gets disillusioned. He flees. He finds her again. Bad things happen. But A Farewell to Arms is so much more than this. It is a heartbreaking love story. It is a remarkably subtle indictment of war. It shows how people bury their romantic longings behind duty and how there’s a greater bravery in fulfilling what you owe to your heart. It argues for life and love. Its final paragraph is devastating. It zooms along with masterly prose that is buried with treasure. It is one of the greatest novels of the early 20th century. This statement is not hyperbole.