Seven years ago, I began The Modern Library Reading Challenge, a series of essays responding to the top one hundred works of fiction, as decided by a few serious-minded literary people on July 20, 1998. Two years into that, when I got stuck on Finnegans Wake, I began The Modern Library Nonfiction Challenge. While I have certainly enjoyed this unique reading journey and I have learned much, I have still felt the nagging sense that something has been severely missing from my life.

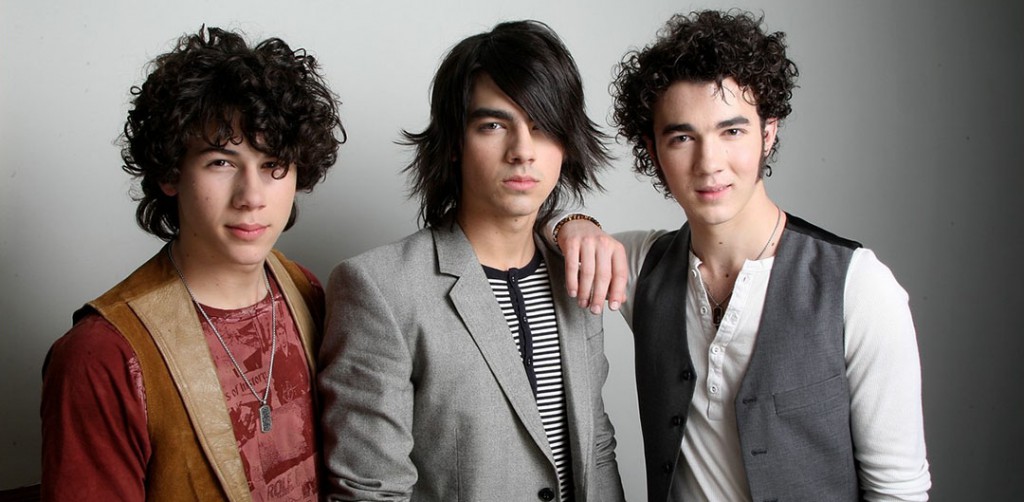

A few months ago, I began listening to the fourth Jonas Brothers album, Lines, Vines and Trying Times at around 3:30 AM. I had stumbled upon the record because I had one of those desperate cravings for Red Vines after smoking too much weed. I had tried Googling for a bodega that was open at that hour and within walking distance and that had Red Vines in stock. Nothing came up. But Lies, Vines and Trying Times did. (In hindsight, I may have typed “no bodega open lies red vines trying times,” hoping that the online oracle, which as we all know is never wrong, would give me the necessary guidance to cope with my existential snacking crisis. Using Google was a far better idea than screaming at the top of my lungs and waking up my neighbors over my angst-ridden failure to buy enough mass-produced licorice to accommodate my late night whims.)

Kevin Jonas’s smiling face appeared near the top of my search results. There was something comforting about seeing a grown man with a toothpick in his mouth. It helped that he had an inoffensive leather jacket and a vague squint. Kevin was obviously much younger than me. For one thing, he had hair at the top of his head that I couldn’t grow back due to male pattern baldness. Some men of my age have found spiked hair to be a threat, but I took comfort in the fact that my beard was thicker than his. Kevin could grow his hair and let it poof upward in sexy straight strands, but he couldn’t go the distance when it came to growing a beard. So Kevin and I were more or less on equal hirsute footing. And the way in which Kevin clenched the toothpick between his pearlescent teeth, holding it in place with a casual matrimonial hand, resembled precisely how I wanted to chomp on a Red Vine at that hour.

I learned that the fourth Jonas Brothers album had a very particular philosophy behind it. Nick Jonas, another Jonas brother — and there were four of them all told, three in the band and another named Frankie who wasn’t in the band but who claimed allegiance to Mephisto on his Instagram account — had told Rolling Stone, “Lines are something that someone feeds you, whether it’s good or bad. Vines are the things that get in the way of the path that you’re on, and trying times — well, obviously we’re younger guys, but we’re aware of what’s going on in the world and we’re trying to bring some light to it.”

Perhaps Nick and Kevin knew something I didn’t. As an audio dramatist, I had written many lines. But since I wasn’t working on a script, maybe the fact that I wasn’t feeding myself lines was also something which accounted for my overwhelming desire to eat Red Vines. Red Vines had certainly interfered with my life, in that I couldn’t seem to shake the idea that I really needed a soft red stick to clench between my teeth (much like Kevin!) and felt that I could not get some decent sleep until I did. As for trying times, well, if the Jonas Brothers were as aware of what’s going on in the world as they claimed to be, then it behooved me to become familiar with their songs.

I discovered that the brothers had thoughts on warfare (“No you can’t have World War III / If there’s only one side fighting / And you know / Whoa oh”), that they seemed to be just as tortured as I was (“If you hear my cry, running through the streets / I’m about to freak / Come and rescue me”), that they could be gloomy (“With every stroke of lightning / Comes a memory that lasts”), an unusually specific sense of direction when it came to intimacy (“So turn right / Into my arms”), and were very fond of comparing toxic lovers to poison ivy, feeling so strongly about the metaphor that they had even imbued “ivy” with an extra syllable.

It was clear to me that the Jonas Brothers were the great tortured philosophers who I had been seeking for many years. Why then had the band broken up? You can probably imagine my shock when I learned that Nick had expressed regrets about being a member. This from the same man who had confidently announced his pot-enhanced erection to Jimmy Fallon? And then there was Joe, the other Jonas Brother, who distinguished himself from Kevin by describing himself as a “former flat hair model.” Joe hadn’t been on speaking terms with his brothers during the fractious period before the band split up.

Since the Jonas Brothers have meant a great deal to me, I have decided to take up the challenge of making a YouTube lip syncing video for every one of their songs over the next year. I recorded my first lip syncing video this morning of “Burnin’ Up” and I hope that my performance does the Jonas Brothers full justice:

UPDATE: I have now lip synced to another Jonas Brothers song. “Lovebug” is Video 2 of 111. #jonasbrothersforever!

Video 3: “Paranoid” for Lost in Williamsburg‘s Phillip Merritt

The full 111 songs performed by Jonas Brothers (and thus soon by me) are listed below:

“6 Minutes” (2006)

“7:05” (2006)

“A Little Bit Longer” (2008)

“American Dragon” (2008)

“Baby Bottle Pop Theme Song” (2008)

“BB Good” (2008)

“Beautiful World”

“Before the Storm” (2009)

“Black Keys” (2009)

“Bounce” (20089)

“Burnin’ Up” (2008) (Lip synced April 1, 2018)

“Can’t Have You” (2008)

“Chillin’ in the Summertime” (2010)

“Critical” (2010)

“Dance Until Tomorrow” (2011)

“Don’t Charge Me for the Crime” (2009)

“Don’t Say” (2013)

“Don’t Speak” (2009)

“Don’t Tell Anyone” (2005)

“Drive” (2010)

“Drive My Car” (2010)

“Eu Não Mudaria Nada em Você” (2010)

“Eternity” (2010)

“Fall” (2010)

“Feelin’ Alive” (2010)

“First Time” (2013)

“Fly With Me” (2009)

“Found” (2013)

“Games” (2007)

“Girl of My Dreams” (2007)

“Give Love a Try” (2008)

“Goodnight and Goodbye” (2007)

“Got Me Going Crazy” (2007)

“Gotta Find You” (2008)

“Heart and Soul” (2010)

“Hello Beautiful” (2007)

“Hello, Goodbye” (2008)

“Hey Baby” (2009)

“Hey You” (2010)

“Hold On” (2007)

“Hollywood” (2007)

“I Am What I Am” (2006)

“I Wanna Be Like You” (2007)

“I’m Gonna Getcha Good” (2009)

“Infatuation” (2008)

“Inseparable” (2007)

“Introducing Me” (2010)

“Invisible” (2010)

“Joyful Kings” (2008)

“Just Friends” (2007)

“Kids of the Future” (2007)

“L.A. Baby (Where Dreams Are Made Of)” (2010)

“Let’s Go” (2013)

“Live to Party” (2008)

“Love is On Its Way” (2009)

“Lovebug” (2008) (Lip synced April 1, 2018)

“Make a Wave” (2010)

“Make It Right” (2010)

“Mandy” (2006)

“Meet You in Paris” (2013)

“Much Better” (2009)

“Nada Vou Mudar” (2010)

“Neon”

“On the Line” (2008)

“One Day at a Time” (2006)

“One Man Show” (2008)

“Out of This World” (2007)

“Paranoid” (2009)

“Play My Music” (2008)

“Please Be Mine” (2006)

“Poison Ivy” (2009)

“Pom Poms” (2013)

“Poor Unfortunate Souls” (2006)

“Pushin’ Me Away” (2008)

“Sandbox” (2013)

“Send It On” (2009)

“Set This Party Off” (2010)

“Shelf” (2008)

“Should’ve Said No” (2009)

“Sorry” (2008)

“SOS” (2007)

“Still in Love With You” (2007)

“Summer Rain” (2010)

“Summertime Anthem” (2009)

“Take a Breath” (2007)

“That’s Just the Way We Roll” (2007)

“The World” (2013)

“Things Will Never Be the Same” (2010)

“This is Me” (2008)

“This is Our Song” (2010)

“Time for Me to Fly” (2006)

“Tonight” (2008)

“Turn Right” (2009)

“Underdog” (2006)

“Video Girl” (2008)

“We Are the World” (2010)

“Wedding Bells” (2013)

“We Got the Party” (2007)

“We Rock” (2008)

“What Did I Do to Your Heart” (2009)

“What Do I Mean to You” (2013)

“What I Got to School For” (2006)

“What We Came Here For” (2010)

“When You Look Me in the Eyes” (2006)

“World War III” (2009)

“Wouldn’t Change a Thing” (2010)

“Year 3000” (2006)

“Yo Ho (A Pirate’s Life for Me)” (2006)

“You Just Don’t Know It” (2006)

“Your Biggest Fan” (2010)

“You’re My Favourite Song” (2010)