BECOMING JANE JACOBS

by Peter L. Laurence

(University of Pennsylvania Press, 376 pages)

Washington Square, which was David Bowie’s favorite place in New York, remains one of the most peaceful congregation points in the city, open to all souls and hospitable to all classes. Its great marble arch spills a lambent glow on the many students, lovers, and artists who talk and love and perform beneath the leafy shadows. Skateboarders ollie around the magnificent fountain. Kids stage epic pillow fights and participate in vivacious lightsaber battles. Stanley Kubrick once played chess here. You will find a slightly grumpy musician hauling out his massive piano on the weekends, dutifully educating any and all receptive ears on classical music. Protesters have gathered here to redress this nation’s many ills. Beatniks (including future mayor Ed Koch) have played their guitars here, fighting valiantly through the ages against ignoble police crackdowns. The park is so naturally welcoming of outliers and oddballs that I have read aloud some of my strangest prose here many times, only to have smiling strangers accost me. “That’s the craziest shit I’ve ever heard,” said one man who gave me a five dollar bill last autumn. “Keep it up.”

Had it not been for Jane Jacobs, this magnificent monument to motley promise might have become just another concrete eyesore.

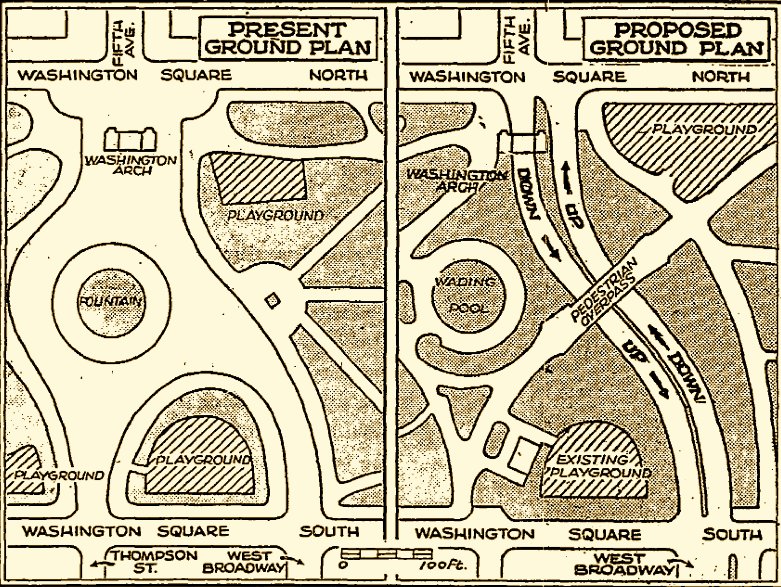

In 1952, the tyrannical urban planner Robert Moses hoped to bifurcate the park with a loud road carrying the bestial name of Lomex (short for the “Lower Manhattan Expressway”), operating under the theory that automobile traffic should not be impeded by anything so fanciful as regular people chilling out on a Saturday afternoon. Moses, as documented with extraordinary detail in Robert A. Caro’s excellent biography The Power Broker, believed that New York City should belong to the cars. He was one of the most feared and inflexible city administrators that New York has ever known. But Moses met his match on the Washington Square fight.1

A brave woman by the name of Shirley Hayes, whose great efforts have often been overlooked by some historians, created the Committee to Save Washington Square Park. Jacobs, who was busy raising a family and writing articles for Architectural Forum, received one of Hayes’s flyers and, immediately recognizing the threat to city life, joined Hayes’s committee, wrote to Mayor Vincent R. Impellitteri and Manhattan Borough President Robert Wagner, and vowed to do anything necessary to fight Moses. The two women bonded over their love of Greenwich Village. Jacobs was greatly impressed by Hayes’s refusal to compromise for a less obstructive roadway. Jacobs began talking with local shopkeepers and started to attend city meetings. And it soon became apparent that the only surefire way to save the park was to make the fight a full-time job.

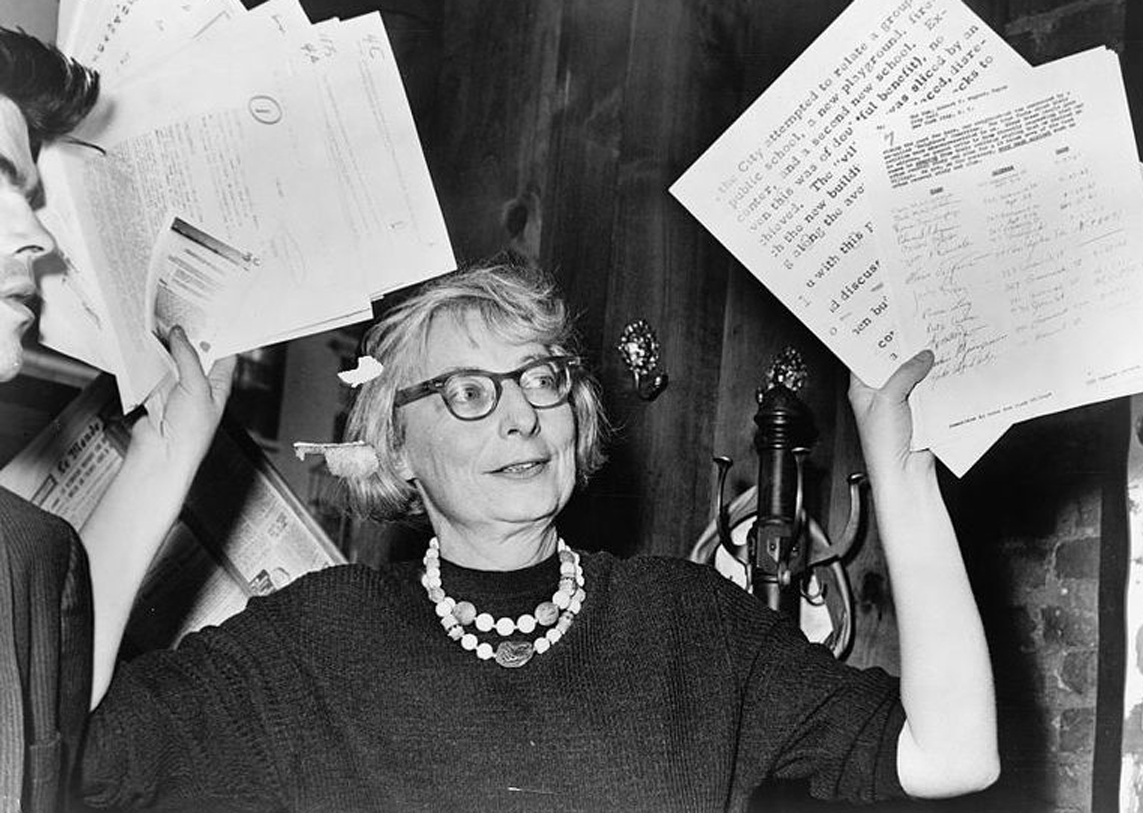

Moses countered with a submerged four-lane roadway alternative, but the neighborhood had caught on quick to Moses’s wily ways. Hayes, Jacobs, and an activist named Edith Lyons were, by this time, bombarding City Hall with thousands of letters opposing this wanton destruction of a major public center. Using her connections, Jacobs persuaded Eleanor Roosevelt, Margaret Mead, Lewis Mumford, Charles Abrams, and William Whyte to join the cause. And because Jacobs was as masterful in administrative acumen as Moses, she broke down the efforts of saving Washington Square into manageable tasks, reminding all in the neighborhood that they must not give into Moses’s efforts to buy them out or compromise. She was also shrewd in humanizing the battle. She often brought her three children with her when persuading the locals to sign the petition.

By 1958, Moses’s narrower road proposal was being seriously considered by the City Planning Commission. The committee appealed to Carmine De Sapio, a slick Tammany Hall man who never seemed to leave home without his sunglasses. De Sapio was then serving as New York Secretary of State. He believed himself to be a soigné sophisticate, but he was on the downslide due to his mob connections, the city’s growing exhaustion with corruption, and his inveterate tendency to sell out judicial nominations. Nevertheless, this somewhat crooked politico was a man of the Village and was one of the rare people who could smoothly resist Moses’s manipulation. (As documented by Caro, De Sapio once turned down an offer from Moses to place all of the Triborough Authority’s insurance money with one of the firms that Mr. Sunglasses was associated with.) And De Sapio, for all of his faults, did feel very passionately about the park. He couldn’t say no to the activists standing outside City Hall with their twirling pink parasols reading PARKS ARE FOR PEOPLE.

By 1958, Moses’s narrower road proposal was being seriously considered by the City Planning Commission. The committee appealed to Carmine De Sapio, a slick Tammany Hall man who never seemed to leave home without his sunglasses. De Sapio was then serving as New York Secretary of State. He believed himself to be a soigné sophisticate, but he was on the downslide due to his mob connections, the city’s growing exhaustion with corruption, and his inveterate tendency to sell out judicial nominations. Nevertheless, this somewhat crooked politico was a man of the Village and was one of the rare people who could smoothly resist Moses’s manipulation. (As documented by Caro, De Sapio once turned down an offer from Moses to place all of the Triborough Authority’s insurance money with one of the firms that Mr. Sunglasses was associated with.) And De Sapio, for all of his faults, did feel very passionately about the park. He couldn’t say no to the activists standing outside City Hall with their twirling pink parasols reading PARKS ARE FOR PEOPLE.

Jacobs and the Committee celebrated their triumph. Moses, never a man to accept defeat without imperious implosion and aggressive paperwork, made a last-ditch effort to widen the streets around Washington Square Park. But by this time, the city had tired of the squabble and hoped to move forward. Moses resigned as parks commissioner, effectively scampering away after Jacobs and Hayes won what had seemed to be an unwinnable fight.

Jacobs’s work in preserving the park gave her the confidence she needed. In 1961, she published her tremendously influential book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Many of the conversations she had with Village residents, along with the information she soaked up while organizing the battle, led to invaluable observations about sidewalks, public life, city grids, the need for neighborhood diversity, and faith in everyday people to forge and evolve great cities. But Moses’s Lomex scheming was from over. In the 1960s, his plans to raze neighborhoods for massive expressways resurfaced. Jacobs would fight these efforts too, this time operating with a working treatise on how to keep cities fun and vivacious. She even wrote a protest song with Bob Dylan and got arrested in 1968 during a meeting.

One hundred years ago, Jane Butzner was born in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Very little is known about her early life. Despite becoming a highly visible figure who went out of her way to speak with the people who created a neighborhood, she was fiercely protective of her private life and was often baffled by anyone who was interested in it. What we do know is that her parents believed that cities were the center of human life. This likely set off Jacobs’s lifetime preoccupation with the effect that cities had on human life, which extended even to the ways in which cities imported and exported products (The Economy of Cities) and even their impact upon nearly all economic activity (Cities and the Wealth of Nations, a smart and often needlessly ignored rebuttal to Adam Smith).

Jacobs wanted to be a writer from a very young age and had pieces published in the Girl Scouts magazine, American Girl, in 1927. She read poetry when she was eleven and continued to write verse well into the mid-1950s, a creative approach that would later be seen in the fictitious city considered in The Economy of Cities, the dialogue drive of The Nature of Economies, and even a children’s book published in 1990 called The Girl in the Hat.

Jacobs long presented herself as a humble woman who just happened to get involved in a major metropolitan scuffle. But a new biography by Peter Laurence, Becoming Jane Jacobs, has cogently argued that Jacobs spent many of her early years honing her knowledge about cities. As a reporter at Amerika, she was nimble in her supervising and editing and quickly worked her way up to publications editor, free to write articles on any subject she learned. At Architectural Forum, she studied urban blight quite closely and proved to be as divergent in her views as her editor Douglas Haskell. Jacobs and Haskell forged a working relationship that was predicated on exploring the social consequences of building. Both were determined to fix problems fast rather than wait around for some shining idealistic model to shimmer into being. Laurence points to the remarkable environment of architectural criticism at the time. Architects regularly threatened any critic with libel. And this resulted in many writers pulling their punches. But Haskell, a quiet firebrand who coined the term “Googie architecture” and who had just received the okay to be more bold and outspoken from the lawyers, told Jacobs that it was okay to throw a few stones.

Jacobs began to critique schools, hospitals, and housing projects in 1952. Laurence, who scoured through the Haskell Papers at Columbia, reveals that Jacobs was not only exceptionally enthusiastic about her work, but determined to publish project reviews before anyone else:

I have a plot to try to get him to change his mind, which I hope works, and it would probably help if he got a note expressing interest in these other things — especially Trenton which we ought to get our hooks into soon if we want it.

Laurence also points to early conceptual kernels that later grow into promising husks for Death and Life‘s wide-ranging fields, such as Jacobs suggesting that a college library build a transparent ramp to create “eyes on the street” (echoing her call for street watchers and good lighting on sidewalks). Yet Jacobs also had to live with Forum‘s misguided legacy, such as an egregious 1951 article (“Slum Surgery in St. Louis,” written by another author) that praised the troubled Pruit-Igoe project. Jacobs never named the source of the article even as she railed against Le Corbusier’s tower-centric excess in her most celebrated book. Yet in these early days, Jacobs was not immune from casting aspersions about urban blight. Her March 1953 essay “New Thinking on Shopping Centers,” which Jacobs later regretted, dispensed platitudes about creating “blightproof neighborhoods” and “higher land values.” In 1955, Jacobs also viewed a Philadelphia redevelopment project steered by Louis Kahn as a ripe opportunity for unslumming.

Laurence also points to early conceptual kernels that later grow into promising husks for Death and Life‘s wide-ranging fields, such as Jacobs suggesting that a college library build a transparent ramp to create “eyes on the street” (echoing her call for street watchers and good lighting on sidewalks). Yet Jacobs also had to live with Forum‘s misguided legacy, such as an egregious 1951 article (“Slum Surgery in St. Louis,” written by another author) that praised the troubled Pruit-Igoe project. Jacobs never named the source of the article even as she railed against Le Corbusier’s tower-centric excess in her most celebrated book. Yet in these early days, Jacobs was not immune from casting aspersions about urban blight. Her March 1953 essay “New Thinking on Shopping Centers,” which Jacobs later regretted, dispensed platitudes about creating “blightproof neighborhoods” and “higher land values.” In 1955, Jacobs also viewed a Philadelphia redevelopment project steered by Louis Kahn as a ripe opportunity for unslumming.

Laurence’s invaluable excavation into Jacobs’s early thinking not only allows us to see a prototype for the clear urban models she was to develop through her activism and her writing, but, as we see Jacobs shed some of her less inclusive views about communities, the early thinking serves as a rebuttal to the kind of wildly misinterpreted absolutism spouted by hacky gasbags at Slate. It is certainly true that the New Urbanists who have followed Jacobs have often been white and affluent. Even as a young man walking around the Marina District of San Francisco, which was in the early noughties nowhere nearly as affluent as it is now, I felt deeply annoyed at how gentrification had aligned itself so neatly with many of Jacobs’s enticing ideas. But anyone who has actually studied Jacobs closely knows that she clearly wanted to plan a city for everyone:

In our American cities, we need all kinds of diversity, intricately mingled in mutual support. We need this so city life can work decently and constructively, and so the people of cities can sustain (and further develop) their society and civilization. Public and quasi-public bodies are responsible for some of the enterprises that make up city diversity — for instance, parks, museums, schools, most auditoriums, hospitals, some offices, some dwellings. However, most city diversity is the creation of incredible numbers of different people and different private organizations, with vastly differing ideas and purposes, planning and contriving outside the formal framework of public action. The main responsibility of city planning and design should be to develop — insofar as public policy and action can do — cities that are congenial places for this great range of unofficial plans, ideas and opportunities to flourish, along with the flourishing of the public enterprises. City districts will be economically and socially congenial places for diversity to generate itself and reach its best potential if the districts possess good mixtures of primary uses, frequent streets, a close-grained mingling of different ages in their buildings, and a high concentration of people.

And because Jacobs was more of a pragmatist than an idealist, Jacobs immediately followed up this passage from The Death and Life of Great American Cities with astute warnings on how diversity is prone to self-destruction (for any dimwitted skimmers banging out malarkey for Slate, that would mean gentrification), prescient caution about how the pursuit of profit for hot nightclubs and tourists “[undermined] the base of its own attraction, as disproportionate duplication and exaggeration of some single use always does in certain cities,” and a deep concern with the way building deprived localities of their diversity. Jacobs was well aware that sustaining a city required constant attention to these details, which was precisely the whole purpose of her final book Dark Age Ahead.

Jacobs’s Washington Square victory was a fight for one component of a neighborhood, not its entirety. And as we celebrate the one hundredth year of her great urban legacy — in an age when Uber and AirBnB have worked very hard to erode the very diversity that Jacobs was championing — her work is a vital reminder to be a part of our community in all its many forms. Our singular perspective is far from the only one.