Lisa Cohen is most recently the author of All We Know.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Working his obsolete connections.

Author: Lisa Cohen

Subjects Discussed: Spending years conducting book research, Esther Murphy, Mercedes de Acosta, and Madge Garland, Garland’s connection to Virginia Woolf, Virginia Woolf’s diaries, the early history of British Vogue, the side effects of spending considerable time in archives, letters exchanged between Greta Garbo and Mercedes de Acosta, befriending Sybille Bedford, Janet Flanner’s considerable connections, Allanah Harper, Olivia Wyndham, Edna Thomas, Flanner’s Letters from Paris, Flanner’s lifelong fear of de Acosta, women who moved in the same Sapphic circle, London, Paris and New York as 1920s cultural termini, conveying the feeling of group life, Garland’s involvement with the peace movement in 1939, Betty Penrose’s excoriating editorial letters, Garland’s abandonment of politics later in life, The Peace Pledge Union, Dick Sheppard, Aldous Huxley, strange friendships with Ivy Compton Burnett predicated on not talking, Garland’s unpredictable qualities, Dorothy Todd’s ostracization from the 1920s social circles, what it took to get ostracized from 1920s social circles, Edna Woolman Chase and the “Nast formula,” the grip that commerce had on 1920s magazines, how the best days of British modernism were in opposition to business, Listen: the Women (a now forgotten radio show that discussed women’s issues long before Friedan), Martha Rountree, Dorothy Thompson, attempts to find radio transcripts, how phonetics journals were instrumental in digging up research, copy editing titles that have an uncertain provenance, Murphy’s vulnerability and volubility, drinking and anxiety during the early 20th century, records of Listen: the Women at the Library of Congress, searching through private collections when public records were sparse, developing a good research filter, how writing a massively ambitious book can change your life, chasing after papers in Melbourne on a calculated whim, getting on a plane to chase one shard of research down, dead ends of superabundance, Edmund Wilson, Chester Arthur, Murphy’s loquacity, being known as a brilliant talker, Murphy spending an entire life working on a study of Madame de Maintenon, Hilton Als’s thoughts on All We Know, Dawn Powell, Murphy’s need to perform, talking and uncontrolled excess, writers ruined by drinking, functional alcoholics, conversational culture predicated upon drinking, whether or not de Acosta was “the world’s first celebrity stalker,” assessing de Acosta’s poetry and fiction, thinking critically about your obsession, distinctive people who arouse strong feelings in others, quirky word usage of “consummate,” de Acosta’s affairs with many leading ladies, the fashion holdings at the Brooklyn Museum, de Acosta’s shoe collection, the desire for a higher education, how education forms character, the pros and cons of passionate engagement, Michael Holroyd’s thoughts on biography, Richard Holmes’s ideas about the rhythm of falling in and out of love with a biographical subject, scholarly frustration, Murphy’s crush on Natalie Barney, movers and shakers on the Left Bank, promiscuity in 1920s Paris, when brilliant people have blind spots, writing quasi-fiction instead of confronting the facts, Dawn Powell’s idea of “piling up facts like jewels,” living a life when all of your friends are literary characters, the dangers of living through books, class and perceptions of Australians, and whether there are any comparable figures today who could match up to Murphy, de Acosta, and Garland.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: So I was flipping around the endnotes in this book. And I noticed that you had actually conducted interviews with some of the surviving members of these various circles as early as ’96, ’97, ’98. I was really impressed by this.

Cohen: Now you’ve seen my dark secret. Not as early as ’96, but…

Correspondent: ’97. I’m sorry.

Cohen: ’97.

Correspondent: Just to be clear.

Cohen: Yes.

Correspondent: But this seems as good a time as any to ask you, first of all, how you found out about these three women. And also perhaps alert our listeners — because these are fairly obscure figures in history, semi-obscure figures in history, Esther Murphy, Mercedes de Acosta, and Madge Garland — who these people are and how you first found them. I was really curious about that.

Cohen: So the question isn’t about why it took me so long to write this book.

Correspondent: No, no. The question is really — well, look, there are people who have spent decades on books. That’s a given. The question is when you first heard of them.

Cohen: I first heard about Madge Garland even before the distant date that you first mentioned. Even several years before then. I was writing an essay about fashion and Virginia Woolf. And I had read around Woolf’s diaries before then. But I hadn’t actually read them as a whole work.

Correspondent: Did you do that from beginning to end?

Cohen: So I read the diaries from beginning to end. And when I got to the mid-’20s, I found that Woolf was in touch with, getting to know these very interesting two women — Dorothy Todd and Madge Garland. Todd was the editor and Garland was her assistant and then the fashion editor of British Vogue in the mid-1920s. And they were remaking the magazine into this, well what you now know, really interesting place.

Correspondent: While we’re on the subject of Dorothy Todd, I was wondering. Because she’s such a prominent supporting character, did you figure that she might be a fourth part? How did you come up with the three part structure here?

Cohen: Okay. Well, that is part of the whole story. Who are they? How did I find them? Why these three people? Why three and not four or not five? In fact, originally, I thought I was writing a book about Madge Garland. As time went on, I realized that I wanted this to be a different kind of book. And I wanted to show her in conversation with, in the context of — neither of those words is quite right. But I wanted to be able to think about the issues that her life brought up in a broader way. And I also wanted to think about the genre, about biography, in a somewhat different way. I became obsessed with this woman — Madge Garland — who was in the fashion world, for your listeners, in England beginning in about 1920, when she started working at British Vogue, almost until the end. She lived into her mid-90s. She died in London in 1990. She was still publishing in the 1980s. Not hugely, but she was writing book reviews and giving interviews and so on. Until really late in her life. So a fascinating figure and a fairly elusive one and someone who told a lot of stories about her life that didn’t quite add up. Which was part of why I got really, really interested. Because I didn’t know what really had happened. And she was making it a little hard for me to find out.

Correspondent: But you were pretty stubborn and seemingly obsessive about getting it.

Cohen: I was pretty obsessed with her. I really wanted to know what had happened in her life. Because I was really moved by her and interested in her. And she was also a way for me to learn about things that I wanted to learn more about. As were all of these women. In any case, it became clear to me that writing a single subject book wasn’t the way to go for somebody like this. And along the way, I wrote a magazine profile of Mercedes de Acosta. So I spent time in the archive in Philadelphia. The Rosenbach Museum and Library, to which she gave and sold her quite voluminous collection of papers.

Correspondent: This was around the Garbo release?

Cohen: No. It was well before that.

Correspondent: Okay.

Cohen: I was invited to the press conference for the Garbo release because I had spent a lot of time in that archive already and had written this profile and got to know the curators and librarians and educators. The really wonderful people who work in that archive. So, no, well before that. Anyway, the third part of this was that I was getting to know — as a result of having interviewed her about Madge Garland, I was getting to know the wonderful writer Sybille Bedford, who talked to me a lot about Esther Murphy, who was her lover and then her very, very close friend until the end of Esther’s life. And who, as I said in the book, was really in many ways haunted by Esther until the end of her life. Sybille Bedford died — again, also when she was in her nineties — in 2006. And I thought that I wanted to bring Madge Garland into contact with these people who were also in her life. They weren’t her lovers. They were her friends. They were sometimes close friends. These women all knew each other. They were all moving in Venn diagram circles. They all had things to say about each others’ lives. They were more or less intimate with each other. They were not lovers. But they were careful and interesting observers of each others’ lives. And by juxtaposing them, I thought I could say something, again, about the genre. I could do something that was challenging and interesting to me as a writer. And I could try to talk about these questions about failure and success, about importance and triviality, about what work is, what it means to produce, what it felt like to be living through that modernist moment. I thought I could give a richer, more complicated picture of that.

Correspondent: Through pure obsession.

Cohen: Through a lot of obsession and a fair amount of self-doubt and persistence.

Correspondent: Yes. Well, I would imagine, since there’s probably nowhere nearly as much information on figures like these three as say somebody else. You mentioned trying to find specific figures who connected the three. And Janet Flanner, who seems to show up and is familiar with all three, is perhaps the most prominent of your supporting cast. What do you think it was about Flanner that allowed her to know these three women? And were there any other links that you tried to incorporate in the book that weren’t actually there of specific people who were connectors or networkers and so forth?

Cohen: You mean, links who don’t end up showing up in the book?

Correspondent: Yes, exactly.

Cohen: Well, I actually did think about that. There were other women I thought about writing about. One of them is Allanah Harper, who is there, but has a much smaller part. Somebody should write about her. Her papers are at the University of Texas at the Harry Ransom Humanities Center there, as are many other amazing writers. And she was part of that lesbian scene in London in the ’20s. And she was close friends with Sybille Bedford. As a result, she was in Esther Murphy’s life. In the ’20s, she and Madge Garland knew each other. There are lots of other really interesting women. Barbara Kerr Seymour, who was a photographer. Olivia Wyndham is another, who also was a photographer. They worked in the same photo studio for a while in London in the ’20s. Olivia Wyndham had an amazing life. She came from this upper-class or upper middle-class English family and basically ran away from home. First to get a job to work as a photographer and live a kind of wild life in London in the ’20s. And then she fell in love with a woman named Edna Thomas, an African-American actress and singer, I think, who was in London performing. And Olivia Wyndham fell in love with Edna Thomas. She moved to New York. She lived the rest of her life in Harlem and in Brooklyn. She actually joined the WACs and worked as a photographer in the U.S. in the army. I think she was sent to Australia in the ’40s during the war. I mean, a really, really interesting life. She has a tiny little part in my book. But someone should write about her. Her half-brother, Frances Wyndham, has written a story that is partly true, partly fictional about her. She appears in Julie Kavanagh’s book about Frederick Ashton. I mean, there are all kinds of women. And Madge was interesting to me originally because I really wanted to try and think about how to write about fashion, which is this non-narrative thing, right? You pop in your clothes. You appear and you make an impression. But I wanted to try and think about how to write about that phenomenon, about style and about fashion, in the story of somebody’s life. In a way that was about the profound effect of how we make our surfaces.

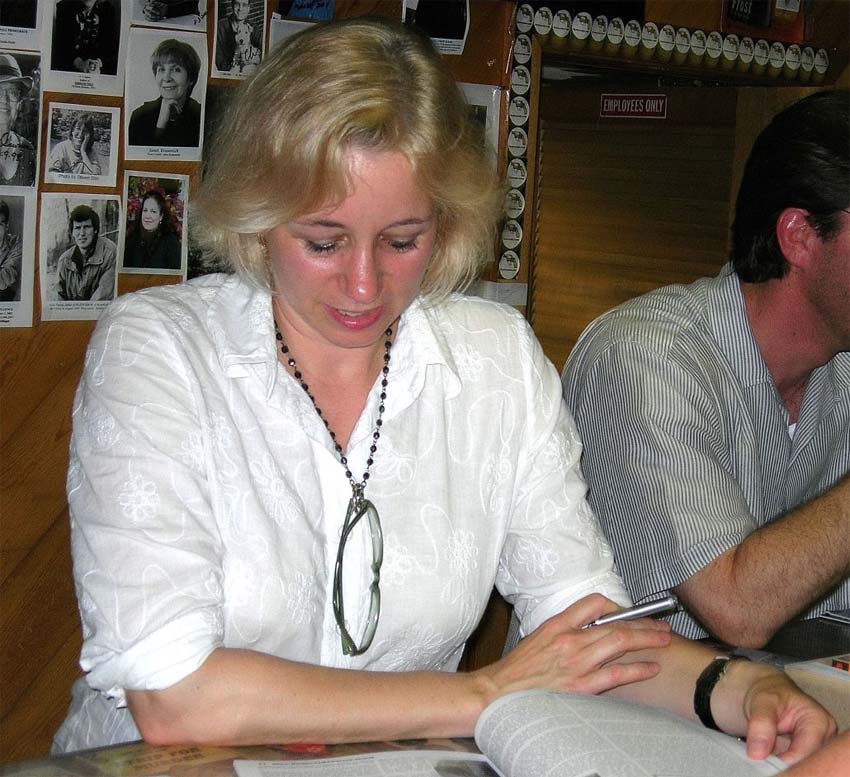

(Photo: Madge Garland, circa late 1920s; the Madge Garland Papers)

The Bat Segundo Show #479: Lisa Cohen (Download MP3)