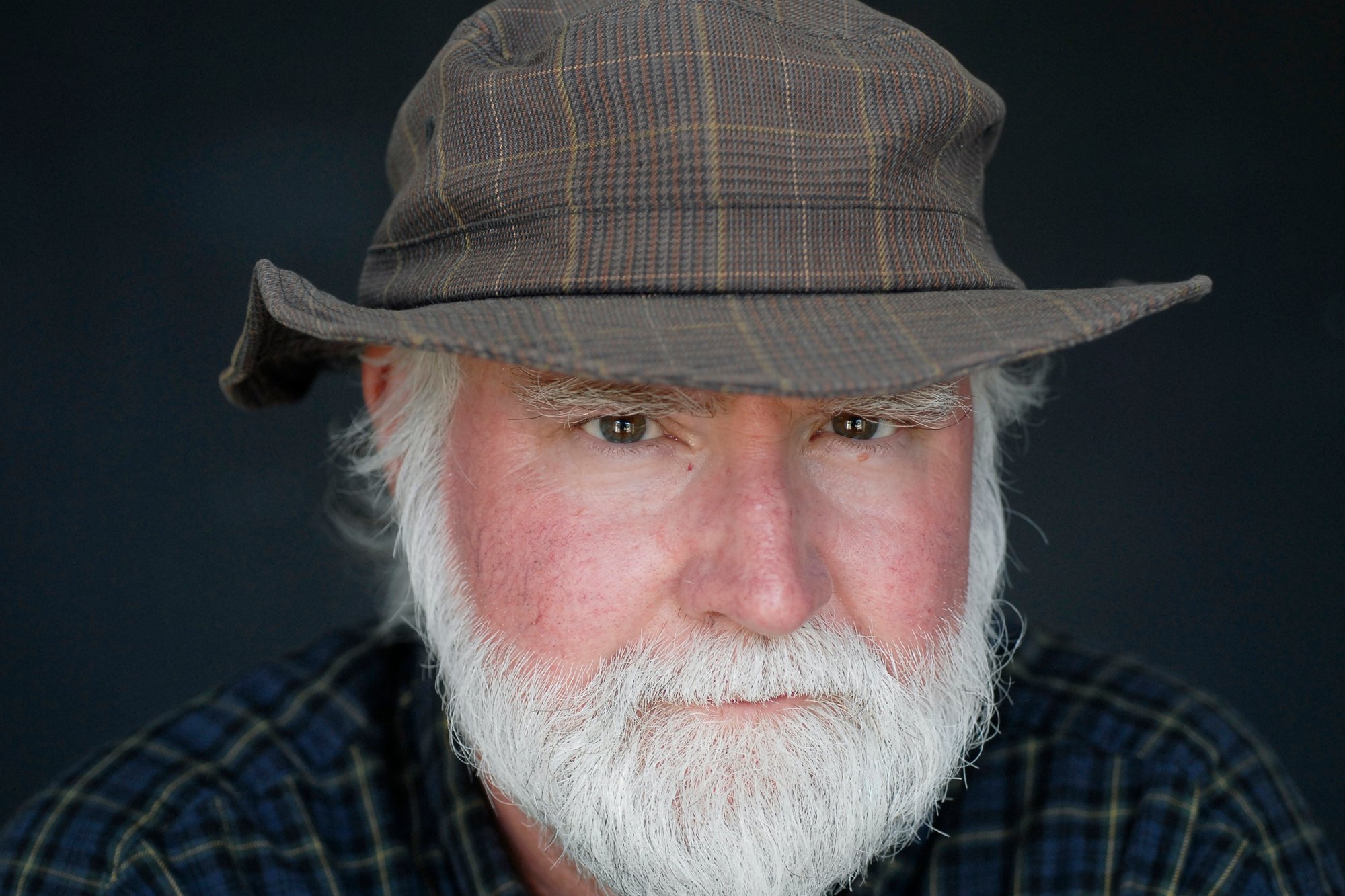

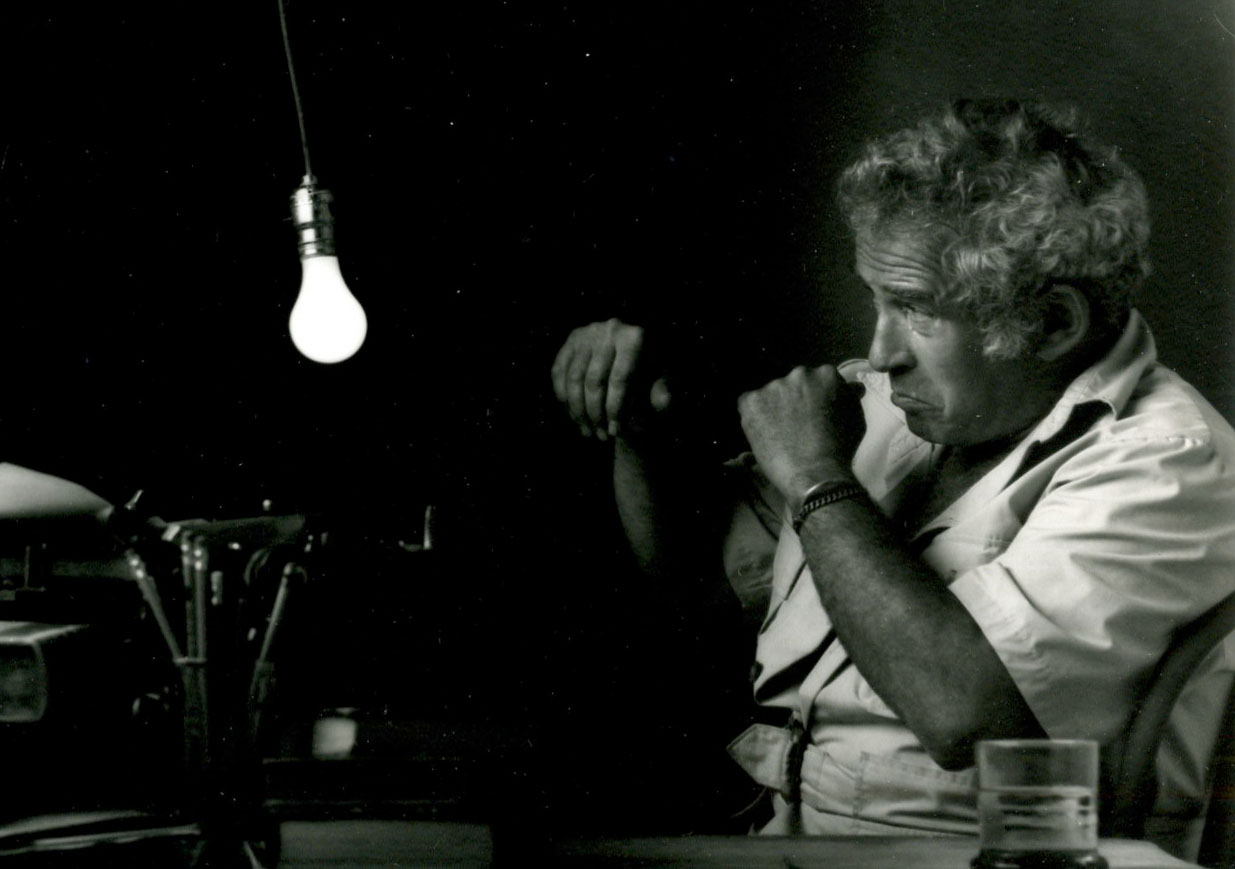

J. Michael Lennon is most recently the author of Norman Mailer: A Double Life. This conversation also references essays contained in the new Mailer collection, Mind of an Outlaw.

Author: J. Michael Lennon

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Subjects Discussed: Mind of an Outlaw, Jonathan Lethem’s thoughts on Mailer, why Mailer couldn’t control his expressive impulses, “Superman Comes to the Supermarket,” Gary Gilmore, addressing thoughts raised by Richard Brody concerning why Mailer didn’t mine from his boyhood, Mailer’s relationship with Brooklyn, the difficulty of finding out about Mailer’s high school days, Mailer vs. Bellow, Mailer’s mayoral results vs. Anthony Weiner’s mayoral results, the formation of Mailer’s politics, how Mailer was manipulated by the Kennedys, Mailer’s bizarre filmmaking career, the “Oh god! Oh man!” moment from Tough Guys Don’t Dance, the Rip Torn/Norman Mailer brawl during the filming of Maidstone, D.A. Pennebaker, the spirit of assassination summer, Mailer as Norman T. Kingsley, when Method acting goes too far, Rip Torn’s Mailer-like qualities, Mailer taking out ads where he quoted from his bad reviews, William Buckley’s joke on Mailer, how Mailer was played as a fool by the literary community before The Armies of the Night, writing An American Dream as a serial novel, Mailer’s hot streak during the late 1960s, Mailer’s battle to write during The Deer Park, prolificity and deadlines, Mailer’s convoluted form of writing discipline, Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain as model, sprint writing, Mailer’s inability to fulfill his ambitious multi-novel project in the 1970s, setting crazed ambitions, the sporadic quality of Mailer’s fiction, Lethem’s “Mailer is parts” assessment, Mailer’s sense of humiliation, Jack Henry Abbott, why Mailer’s efforts to spring Abbott weren’t as influential as people thought, how Mailer left Abbott to be cared for by Norris, why people believed in Mailer, the belief culture of the 1970s, Abbot’s murder of Richard Adan, Mailer’s famous “culture is worth a little risk” remark, Mailer’s belief that there was a morsel of good within very evil people, literature as a way to save your soul, Mailer’s willingness to appear foolish at a press conference after Abbott vs. Dave Eggers’s silence in response to Abdulrahman Zeitoun, Cynthia Ozick’s famous response to Mailer in Town Bloody Hall, Germaine Greer’s desire to sleep with Mailer, Mailer’s disastrous positions on feminism and women writers, Mailer’s simultaneous fury and chivalry, Mailer’s forthcoming letter collection, the stabbing of Adele Morales, why Lennon didn’t reveal details about his telephone conversation with Adele, responding to Louis Menand’s criticisms, The Last Party, how Adele has lived in recent years, other first-hand accounts of the party, Mailer’s diary, why the literary community forgave Mailer easily and ganged up on Adele Mailer (and blamed her for the stabbing!), what men were able to get away with in the pre-feminism days, Mailer’s bizarre pattern recognition schemes, his interest and Reich and the orgone box, the Kakutani file, Mailer’s attempt to connect biorhythms to a football team’s success, why Mailer was receptive to charlatans, how Mailer detected bad omens in rooms, transcendentalism, Mailer’s numerous accents, Dwight Macdonald, Brendan Behan, Mailer’s love for The Sopranos, Mailer’s attempts to escape his identity, why people kept coming back to Mailer, Mailer’s desire to know other people’s stories, Mailer’s sensitivity to interruptions, serving as Mailer’s bartenders, Mailer’s relationship with Gore Vidal, Mailer referring to himself in the third person in his nonfiction, Occupy Wall Street, how The Armies of the Night came about, Picasso’s influence, Henry Adams, early stylistic versions of The Armies of the Night, the difficulties of putting yourself in a story, Mailer’s formidable memory during The Armies of the Night, Robert Lowell, the 1967 March on the Pentagon, Noam Chomsky’s influence on Armies, how Alfred Kazin and Joan Didion’s reviews saved Mailer’s reputation, the contemporary decline of culture, cultural engagement, and contemplating whether today’s conditions could allow for a Mailer type today.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: I want to get into this book by tying it into this recently published collection, Mind of an Outlaw, which I also have right here and I have also been reading. Jonathan Lethem’s introduction contends with thoughts he had previously voiced in an essay that was collected in The Ecstasy of Influence. He points out that he “buried the man before I even began to try to figure out how to praise him.” Part of accepting Mailer, I have found in both reading the biography and in reading the essays and in reading various other work, is that you have to put up with the fact that he will say something utterly brilliant one minute and then he’ll say something utterly foolish the next. He will trash Waiting for Godot without actually bothering to see it. He will dig himself out of a hole of his own making. So why do you think Mailer could not really control these expressive impulses? Why did he need to court disaster?

Lennon: Well, you know, some questions answer themselves by being asked. He couldn’t control his impetuous nature. He was — I’ve said it many times — the most impetuous person I’ve ever met in my life. If he felt the instinct, he followed the instinct. And that’s part of it. His notion of the existential life was “Listen to what’s going on inside you. Don’t preplan everything. Don’t have guidelines and rules and restrictions and guide ropes. Jump into life.” And what did he say? He said, “It’s better to expire as a devil in a fire than an angel in the wings.” So it was part of his nature to be that way. And so he got himself in a lot of trouble. With the feminists, with literary critics, with his friends. By being impetuous, outrageous. In his literary criticism, I felt that it was sitting next to him in a little bar in Provincetown, drinking bourbon with him, and listening to tell stories about Gore Vidal and James Jones. Because his literary criticism can’t be separated from his intimate personal knowledge of them.

Correspondent: This is the rare case where you actually have to know his life to know his work.

Lennon: Yes, I think you do. I really do.

Correspondent: Well, the title of this book comes from a famous passage in Mailer’s essay, “Superman Comes to the Supermarket,” where he points to how American history was moving along two rivers: one visible, the other underground. Mailer also spent much of his life trying to wrestle with this saint and the psychopath duality, which he was later to apply to Gary Gilmore. You’ve traced the origins of this to Mailer reading Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling and I’m wondering to what degree Mailer’s dualities come from concepts that he read and he wished to hold onto in his mind and he wished to play around with in this elastic, impetuous nature of expression.

Lennon: I think that the reading came a little bit later, but it was a confirmation. He was forever finding confirmations for what he sensed were the two people living inside him. And where did that come from? Well, I think initially it came from the fact that, when he was a young boy growing up in New Jersey and in Brooklyn, he was the center of attention. Everything was focused on him. And yet when he went out into the Brooklyn streets, he was a skinny little kid. There were a lot of Irish tough guys around. He was fearful. He was timid. He was small. And he realized that there was this gap between the two sides of his life. He was no one on the streets and he was everyone at home. I think that was the beginning of it. And then he looked for confirmation of that in places. And when he read Kierkegaard, seeing that there were a lot of connections between the saint and the psychopath and in their passionate way of living their lives, he realized there’s the clue. That was one of the clinchers for him. Absolutely.

Correspondent: What’s interesting though is that you point out that there really isn’t a lot of information about his high school days.

Lennon: Right.

Correspondent: And I’m wondering. What searches did you do to try to find something out? I mean, was it just that everybody was dead? Or nobody wanted to talk? What happened here?

Lennon: My chief sources for his high school years were some of the other biographies where people interviewed some of his friends, but also his sister. His sister and her best friend Rhoda: two young women who were a couple of years younger than Norman, but who watched him. They knew his girlfriends. They knew what was going on. They found him to be an utterly charming person. But Mailer said that his life was kind of quiet. He’d go to high school. Everybody thought he was studious, quiet, boring. And when he went home, he had to do homework. He had to go to Hebrew class, religious classes which he loathed, but he went anyway for a long time. And there wasn’t really that much time. I mean, the friends that he had said Norman didn’t get out much. They kept him on a close leash. I know that somebody just wrote a piece on the New Yorker blog.

Correspondent: Richard Brody, yeah.

Lennon: Richard Brody. Wonderful piece. But he said Mailer never wrote a Brooklyn novel. He did. He wrote a novel called No Percentage and it’s set in Brooklyn. He also wrote thirty short stories about Brooklyn when he was in college. So, you know, writing thirty short stories, writing an unpublished and unpublishable novel which is set in Brooklyn, and then, of course, The Naked and the Dead has a couple of real Brooklyn characters in it. Writes Barbary Shore, which is also a Brooklyn novel. I think he was sick of Brooklyn by the middle ’50s and he didn’t want to write about it anymore and he felt that not much happened to him in high school. There wasn’t an awful lot to write about. He was a good student, but good students were boring. I mean, athletes were the heroes.

Correspondent: But it was rather curious. I thought Brody’s essay was extremely interesting.

Lennon: It was.

Correspondent: Because he seemed to think that, because Mailer couldn’t actually look backward in adulthood, this crippled his ability to write fiction. And he had a lot of trouble writing fiction between the years of The Naked and the Dead and The Armies of the Night.

Lennon: Yes, he did.

Correspondent: So is there any kind of biographical information to sort of back that up? Did he make any kind of plunges into his boyhood after these stories you mentioned in later years? Or anything like that?

Lennon: No. Brooklyn was always a touchstone. When he wrote Miami and the Siege of Chicago, he compared Chicago to Brooklyn. He said that they were very similar, that there was a lot of life, that there was a lot of reality, that there were authentic people. He liked that about both Brooklyn and Chicago. Of course, he wrote An American Dream in 1964 and 1965. That was a Manhattan novel. But it was still a quintessential novel. And you got the feeling that Rojack was a guy who had escaped from Brooklyn and made it in Manhattan. And, of course, in those days, that’s what everyone wanted to do if you came from Brooklyn. They wanted to make it in Manhattan. So I think that Brody makes some wonderful points, but I feel that Mailer didn’t want to get bogged down in Brooklyn. Oh, there’s another point too. I was talking with Mailer’s sister about it this morning. And she said, “I can tell you another reason he didn’t want to write another novel about Brooklyn.” She said he read Meyer Levin’s novel, The Old Bunch. And while it’s set in Chicago, he read it and he goes, “This is it! He’s caught the middle-class Jewish family. I can’t ever improve on this!” And he loved that book. So there were multiple reasons for it. But also I think the fundamental reason was that Mailer wanted to play on a bigger stage. He wanted the New York stage and that wasn’t big enough for him. He wanted America to be his stage. He didn’t want to be seen as merely a Brooklyn writer.

Correspondent: It’s interesting how he really admired Meyer Levin, but actually dissed Augie March, which to my mind is the quintessential American novel.

Lennon: I couldn’t agree with you more. But I think Mailer was so competitive with Bellow. He rarely had a good word to say about Bellow until the ’80s. Everything he said about Bellow: Bellow was basically a professor who was spewing out his old ideas from his classes on the Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago and he wasn’t really getting out and experiencing life. Which Mailer felt he was doing. Did he have a good word? You know, in his literary criticism, he finally admitted when he read Henderson and the Rain King, he said, “Alright. I’m going to eat crow. This is a hell of a character worthy of Huckleberry Finn.” So he had that generous streak, but it vied with the competitive steak.

Correspondent: I wanted to actually get into Mailer’s politics. I’m sure you’re familiar with this, but I noted this. It’s worth pointing out that when Mailer ran for Mayor of New York in 1969, he received 41,000 votes in the primary. 5% of the vote. That is actually a good deal more than Anthony Weiner, who received a mere 34,192 votes in the recent primary. Times have changed. But you point out in your biography that Mailer came to politics late. You have Jean Malaquais. He prepares this political tutorial for Mailer that he engages in between October ’48 and March 1950. And before this, he’s relying very much on Spengler as his guide.

Lennon: Yes.

Correspondent: He was spurred on to run for Mayor because of the success of “Superman Comes to the Supermarket,” which has actually large sections that don’t have anything to do with politics and is more almost a continuation of “The White Negro.” So I’m wondering about this. Why didn’t politics factor into the Mailer psyche earlier than this? Did he need to actually be ushered in with the attention and the adulation? Is that how this worked with him?

Lennon: Yes, it is. You’ve put your finger on it. He found out that he could be a player. Remember in 1948, he campaigned hard for George Wallace. Made thirty speeches.

Correspondent: That’s right.

Lennon: In Hollywood and mainly in New York City. He put his heart into it. He thought that the progressive elements were going to win. Wallace got slaughtered. He got a couple million votes in the entire country. Mailer was completely alienated. And that’s, of course, when he began to go underground. The Village Voice and all the years moving into the country. Trying that out. Moving to Perry Street in the Village and trying that out. Flirting with the Beats and so forth. And then when Clay Felker said, “You know, Mailer’s got huge ambitions. He says he wants to be President of the United States. Maybe he’d be a good guy to cover the 1960 campaign and so forth.” There was no plan to write an essay about Jack Kennedy. It was supposed to be about the Convention. Well, Mailer was just blown away by Kennedy’s good looks, his charm, his war record, and all that. And he wrote the piece. And then he gets a letter in the mail from Jackie Kennedy telling him it’s the best political writing she’s ever read in her life and it’s fantastic and why can’t anybody write like that. And Kennedy wins. And Mailer immediately says, “Well, you know, I helped win this election for Kennedy. I might have shifted some votes.” And it’s possible that he did. Because Esquire was a hot magazine then. People were reading it. Based on that, he decided on the spur of the moment, within a week or two after that article had appeared, he decided to run for Mayor of New York City and jumped in two feet. His sister told me, “You know, we thought he was crazy. You know, we’re a middle-class family. He has no political connections. No ties. We thought he was nuts.” Everybody thought he was nuts. But this was in the period where he had Napoleonic aspirations. He was right on the edge of going really nuts.

Correspondent: Well, the other interesting thing about Kennedy, which is actually quite funny, is that Mailer is very insistent in that essay, “I highly doubt that Kennedy would have planned to say that he had read The Deer Park before The Naked and the Dead.” But we learn. Au contraire. He was advised, “Hey, Jack, if you really want to impress him, why don’t you mention that you read The Deer Park rather than The Naked and the Dead.” So he was so willing to believe that he was the king.

Lennon: That’s right.

Correspondent: And I’m wondering if just having those blinders on is what propelled him. It’s really fascinating that a figure like that could last. I mean, it’s inconceivable today that a figure like that, operating off of pure impetuous blinders, could still be fairly revered. Even in this wandering period where he’s writing all these crazy columns for the Voice and all that.

Lennon: Well, you know, the question of whether Kennedy read The Deer Park is a very vexed question. On the one hand, Kennedy says it. But we know he was briefed to say it. Mailer said, “Well, even if he was briefed, that shows that his advisers had good instincts. And Kennedy hired them. So I like him for that.” But then he got the letter from Jackie Kennedy. And she said in the letter, “I remember Jack reading it on the second floor of the house in Hyannis Port. And he did read it.” I mean, I don’t know whether someone prompted her to say that or whatever. She said, “And then I read it. I read it when I was out on the campaign with Jack.” So whether he actually read it or not, I don’t know. But it doesn’t strike me as the kind of thing Jackie Kennedy would make up. I mean, how important would it be to do that? But maybe she did. The Kennedys were notorious for attention to detail.

Correspondent: My theory is that Jackie actually read it and Jack did not. She’s covering his ass basically, saying, “Well, I happened to read it too!”

Lennon: (laughs) That’s right.

Correspondent: And then she can talk about it with Norman. Because guess what? He’s not going to talk with Kennedy again.

Lennon: That’s a good appraisal. It’s very possible it worked out that way.

The Bat Segundo Show #523: J. Michael Lennon (Download MP3)

Correspondent: But this also leads me to go back to the question of the sandwich. I mean, I get that calories were new. They were in the air. People didn’t make any distinction between the calories one received from sugar and the calories one received from an apple. And there are a number of forms of advertisement you depict in this book that show that candy manufacturers played into this and used this to manipulate the public into buying more candy. But with things like the Chicken Dinner bar, I’m just absolutely curious about why something like that could be on the market for so long and yet you say that it’s lost to history. The taste. I mean, certainly there’s someone out there who knows about it and there’s someone out there who has a sense of how many of these sandwich-realted chocolate bars were actually eaten between the clock, so to speak.

Correspondent: But this also leads me to go back to the question of the sandwich. I mean, I get that calories were new. They were in the air. People didn’t make any distinction between the calories one received from sugar and the calories one received from an apple. And there are a number of forms of advertisement you depict in this book that show that candy manufacturers played into this and used this to manipulate the public into buying more candy. But with things like the Chicken Dinner bar, I’m just absolutely curious about why something like that could be on the market for so long and yet you say that it’s lost to history. The taste. I mean, certainly there’s someone out there who knows about it and there’s someone out there who has a sense of how many of these sandwich-realted chocolate bars were actually eaten between the clock, so to speak.