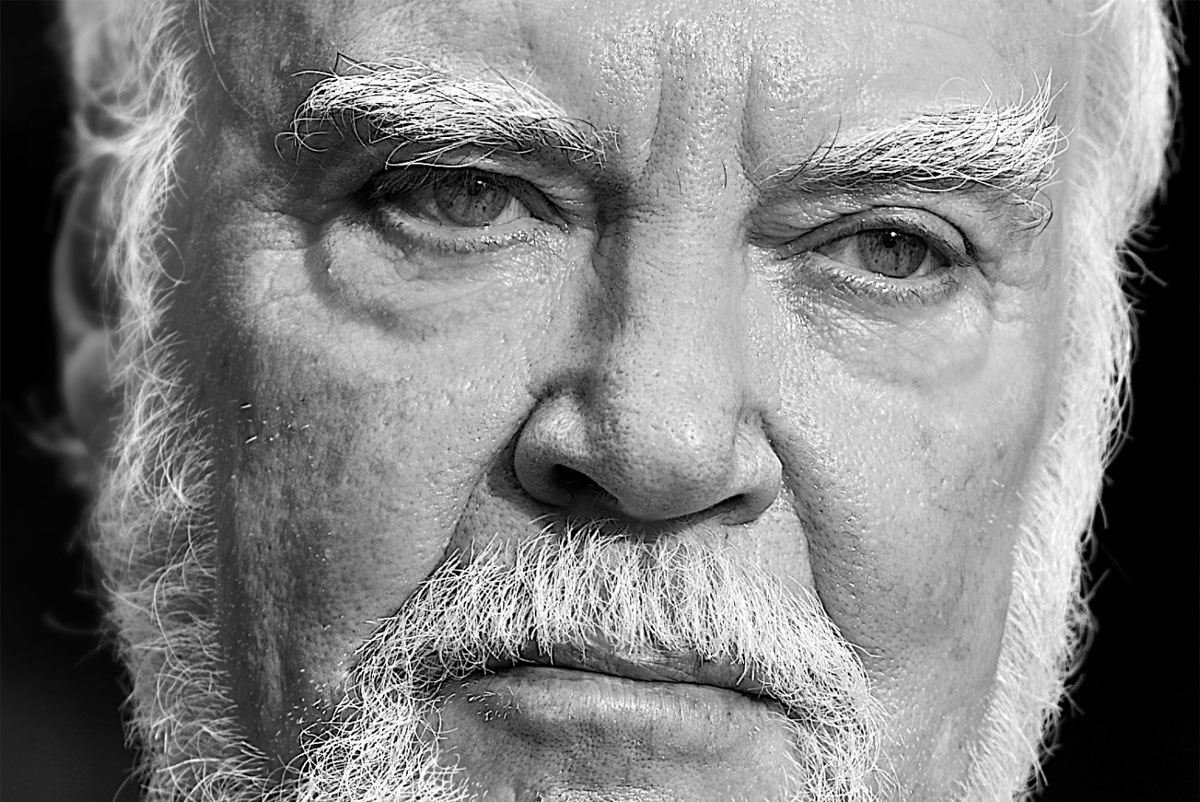

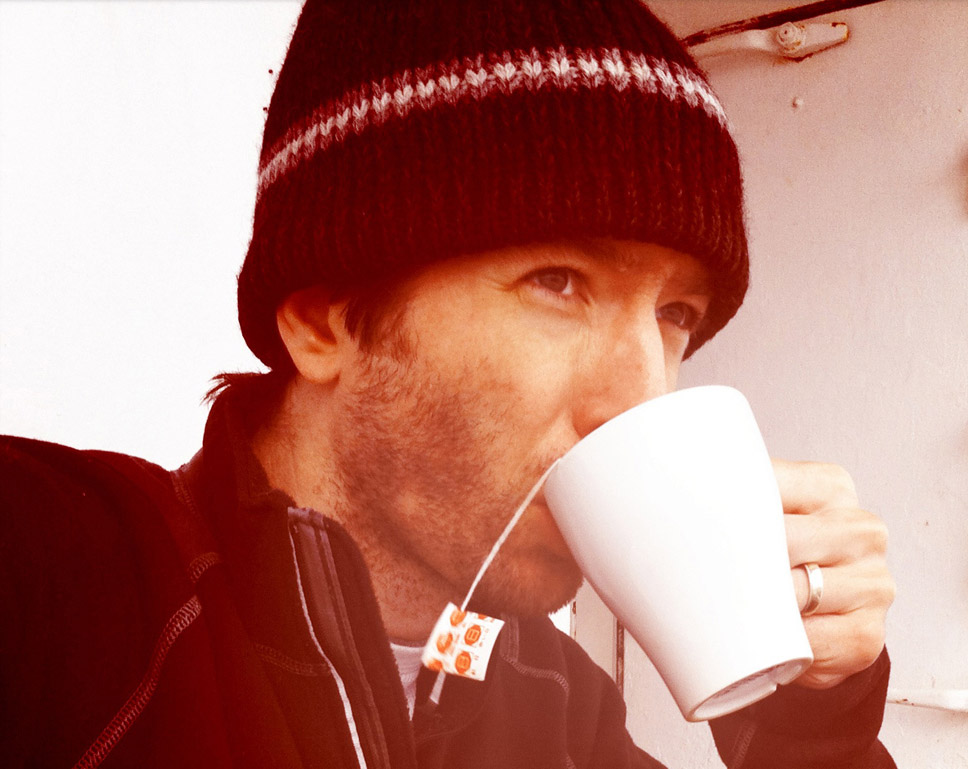

Kiese Laymon is most recently the author of the novel Long Division and the essay collection How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America. This show is the first of two related programs devoted to the American epidemic of gravitating to mainstream culture in an age of limitless choice. (You can also listen to the second part: Show #514 with Alissa Quart.)

Listen: Play in new window | Download

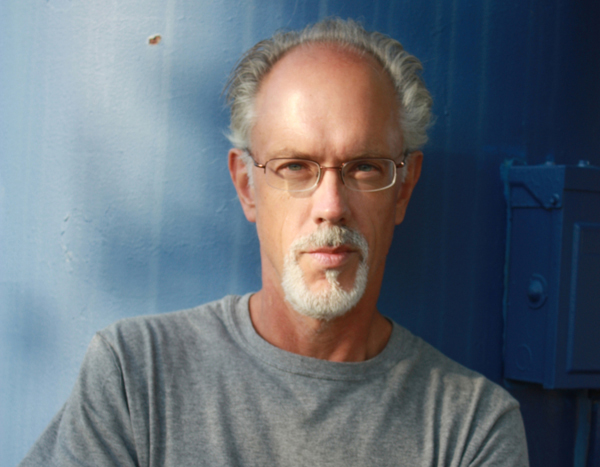

Author: Kiese Laymon

Subjects Discussed: Meeting people under bridges, Percival Everett’s Erasure, Mississippi teens who run away from narratives, throwaway culture, the importance of stories carrying you through the day, critiquing storytelling skills as a way of understanding the truth, alternative narrative identities as methods of accounting for unspoken national problems, how New York rappers spoke to Mississippi black boys, black Southerners as the generators and architects of American culture, active listening vs. culture as background noise, lyrics and storytelling, native Mississippians who aren’t familiar with the blues, the acceptable level of American cultural engagement, sorrow songs vs. the Ku Klux Klan, standing up for Mississippian culture, people who don’t care about the origin to the soundtracks of their lives, national cultural awareness through regional cultural awareness, tourist notions of regions through culture, New Jersey’s history of serial killers and crime, blind engagement with the South, the refusal to hear what people are literally saying to us, dying as a backbone for Mississippi music, interrogating death, Bessie Smith and the 1927 flood, Big K.R.I.T., running away from the gospel tradition, Octavia Butler’s Kindred, whether time travel stories require a moral equilibrium, America as a crazy-making narration that doesn’t want to accept how crazy it really is, grandmother roles, “How to Kill Yourself and Others in America,” being kicked out of college for not checking out Stephen Crane, how the act of committing everything to memory guides you through life, the desire to hold on to innocence, how Laymon’s early writing was denied and disapproved and disparaged, why all 19-year-olds are lunatics to some degree, satire and observation, the important of implicating yourself, Teju Cole, frat culture, sexism and classism, living with druggie roommates, when certain college kids aren’t incriminated and imprisoned (while others are), how bravery helps you make better decisions, individual guilt and societal guilt, the 50th Anniversary of the March on Washington, sanitizing the truth about racial inequality, the capitalist-commercial nexus and its impact upon airbrushing culture and narrative, why Obama cannot tell the truth, getting the President we deserve, “The Lost Presidential Debate of 2012,” “The Worst of White Folks,” how the state is trying to convince that we are good people (while the community tells the truth), Black Power and nostalgia, Stokely Carmichael, egomaniacal misogynists and ideological commitment, Martin Luther King and token Google Doodles, white folks who don’t share power, why we aren’t able to look at the sentences, interrogating mythology, superficial dissections of pop culture from white people (e.g., Slate Culture Gabfest), Miley Cyrus and the politics of twerking, white appropriation at the MTV Video Music Awards, Brooklyn gentrification, Robin Thicke, Justin Timberlake taking the Michael Jackson Award, society’s failure to implicate itself, how Bernie Mac, Michael Jackson, and Tupac were eaten alive by American culture, recklessness as spectacle, how Michael Jackson projected what we didn’t want to talk about, Tupac’s hologram at Coachella, living in a world surrounded by digital ghosts of sanitized cultural figures, Tupac’s music before Death Row and the downside of selling tickets, the label “Black Twitter,” white people on Twitter, #solidarityisforwhitewomen, important work that goes on without white people, the slipshod involvement of mainstream feminists, how race changes the moral focus, slavery and the Holocaust, and making deals with evil terms.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

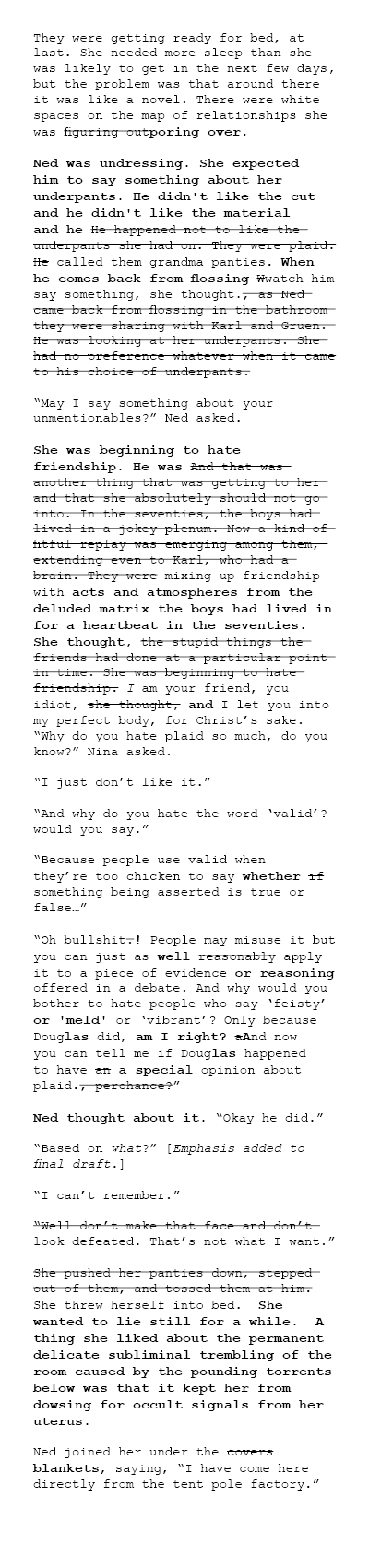

Correspondent: So let’s start with Long Division, which is truly a tale of two Cities. You have this kid named City. He’s in 1985. He’s in 2013. There’s a book called Long Division within Long Division. And this reminded me very much of Stagg R. Leigh’s My Pafology in Percival Everett’s Erasure. I’m wondering — just because we have to ask you how this book got started — to what degree were you responding, like Percival Everett, to limited literary representation of the African American experience? And how was this a way for you to explore versions of City in 1985 that you couldn’t pursue in the present day?

Laymon: That’s a great question. I think I had to make it a metafictive book, particularly because I wanted the characters to consciously and unconsciously be exploring not just the lit that came before them, but the literature that they read that came before them. So there’s a literary mechanism in place that I’m critiquing as an author. But I wanted to create two different Cities who are also dudes who are 14 and very aware of the lit that they read. And they’re really aware of canonical lit. So there are important scenes. There’s a scene in a principal’s office. There’s a scene in the library where I think that, with these two Cities, we can see them actually trying to become runaway characters. But if they’re going to be runaway characters, I had to position them as characters in some way fully aware of the lit that they’ve read, but not fully aware of the narratives that they’re running away from. So the narratives that they’re running away from are different from the books that they’ve read. And part of the book is that they’re trying to figure out what constitutes this narrative that they’re running away from. And as a writer, obviously, I’m thinking about a lot of African American/black Southern lit. Black Boy particularly. But I wanted them to be running away from literature that they read. Which is really important for me.

Correspondent: Well, I’m glad you mentioned that. Because at one point, City has to stay with his grandmother in Melahatchie, Mississippi. His reading library there is largely this kind of throwaway culture.

Laymon: Right.

Correspondent: Centered around classical books with a capital C and the Bible. And as you write, “I didn’t hate on spinach, fake sunsets, or white dudes named Spencer, but you could just tell whoever wrote the sentences in those books never imagined that they’d be read by Grandma, Uncle Relle, LaVander Peeler…” — his frenemy — “…my cousins, or anyone I’d ever met.” So this leads me to ask. I mean, why do you think that in the South, for these characters especially, that their notion of what it is to be alive is so rooted around books? To what extent were you limited in these areas? You and City? Why is that such an important definition?

Laymon: Well, you know, a lot of people have called Mississippi and particularly the South generally the home of American storytelling going way back to Twain and what not. And so story telling and story listening are part and parcel of our culture. Particularly if you grew up in a really religious gospel kind of household. I grew up in stories, but they were stories that were carried through music or language or stories you had to read in the Bible, and stories that my grandmother told me when she came home from work. Stories just carried the day. So I wanted to create two characters that were hyperaware of stories, of storytelling, and really critical of storytelling. The book starts with City critiquing LaVander’s storytelling ability. And LaVander is critiquing City’s storytelling ability. But by the time City gets to that library, what he’s trying to say is “I’m not being completely reactionary. I get that there’s some great cynicism in these books. But I don’t know what to do with the fact that these people never imagined anybody like me reading these texts.” And so for him, at this point, he really believes that audiences are the bedrock of sentence creation. Like to whom are you writing a sentence to? And so when he gets in that library — and it is throwaway culture in a way. So much happens in there. He sees himself for the first time on the Internet, right? He sees the way that he’s presented to other people. And I just wanted to create characters who were not too precocious, too smart, too witty, but in some way wholly aware that stories carry everything.

Correspondent: So what they read is almost an alternative identity that the United States as a whole can’t actually accommodate because of the many interesting questions of race that are in this book.

Laymon: Absolutely. And this is where literature is particularly important. Because with the references to hip-hop early on, hip-hop has been critiqued. I’ve critiqued it. Will continue to critique it. One of the things that hip-hop did, I think, early on for young black boys is that it was an art form that was made popular, that was talking directly to you as a fourteen, fifteen, sixteen, seventeen year old. At least you thought that. When you get geographically specific, you start to see that a lot of these rappers from New York weren’t talking to Mississippi black boys. But you felt that you were being talked to anyway. So one of the things that these characters are really trying to deal with is what happens to the characterization of a real person and a character who is so often not written to people who look just like them. And as we see early on in the book, we get this narrative imposed on them. And they’re trying to break out. And LaVander sort of does break out. But there’s a price to pay for that breakage. But it’s all about narrative creation.

Correspondent: Yes. I’m glad you brought up hip-hop. Because I wanted to talk about “Hip Hop Stole My Southern Black Boy” — one of the essays. You point to how black Southerners are “the generators and architects of American music, narrative, language, capital, and morality.” You point out that the South not only has something to say to New York, but it has something to say to the world. And I’m wondering why you think the world is so unwilling to listen. How much of this resistance to Southern innovation has to do with people who remain too caught up in some of these B-boy routines?

Laymon: I think the world is listening. But I don’t think the world knows what it’s listening to. You know what I mean? There’s no doubt the world is listening to really rock, R&B, and I would even argue funk that has its root in the Deep South. The world is listening to gospel music. The world is listening to blues right now that has its roots not just in Mississippi, but that Deep Southern, South Central culture. They’re listening. They’re dancing to it. They’re making love to it. They’re talking to it. It’s the music that scores our movies. But I don’t really think we know or, I should say, I don’t know if I fully know. I don’t think we’ve taken enough time to think about where that music actually comes. Like what people created, originated, innovated that music and why. Do you know what I mean? So I think to me that they’re listening. They have to listen. Because it’s everywhere. There’s no question.

Correspondent: But are they actively listening? I think that what you’re suggesting is that it’s music that plays in the background without people actually comprehending that there’s a lot of years and blood and tears that’s put into that music.

Laymon: No question.

Correspondent: And people are just not really curious enough to investigate that. I mean, I’m wondering if that’s a larger societal problem.

Laymon: Yeah, I think it is. I mean, this is what I’m saying. I don’t think we take the time to question the ingredients in art generally.

Correspondent: Sure.

Laymon: I haven’t been in many parts of the world. But as an American, I know that we don’t really take the time to consider what we’re consuming. And we definitely don’t take the time to consider the lives of the people who created the music. So even if we think about hip-hop, people who think they love hip-hop have no idea who Kool Herc is. People who think they love hip-hop have no idea who the people who helped create the culture actually were, what they did, and why they did it. So in some ways, it’s not specific to black American/Mississippi culture. But I do think that these particular stories that come out of Mississippi culture — it’s just ironic that the blues, rock, and gospel all come out of this really small part of our country.

Correspondent: I agree. But I’m wondering who to impugn here. (laughs)

Laymon: Well, I think we impugn everyone.

Correspondent: Yeah.

Laymon: And that’s a loose answer. But I was just in Mississippi for nine or ten days giving readings and stuff. There are people in Greenwood, Mississippi and Greenville, Mississippi — black people — who have no clue what the blues is. You know what I’m saying? And what I’m trying to say is that I don’t know what it is. But it is expiration that, because of my parents and because of my grandparents, we’ve had to go on. I’m saying that we don’t even want to go that road. Because when you go down that road, you don’t just find sound. But as you said, you find the experience. And you find complicity.

Correspondent: And if you listen very closely to the lyrics, you have all these amazing stories. Listen multiple times. There’s some cadence that you didn’t get.

Laymon: And also what’s important about the lyrics is that I think it’s really important to transcribe, to see the lyrics on the page. But what’s important about those lyrics are being spat or sung or, in some instances even before hip-hop, rapped. This kind of rhythmic hip-hopesque way of approaching music, I think, predates what we call hip-hop. I know New York people hate for me to say it. But what I’m saying is that it’s not just the lyrics. It’s how the lyrics are said and what irony has to do with the way those lyrics are being spat And I think it has so much to do with community. And these books, particularly Long Division, are, among other things, about community storytelling. And so what I’m trying to say is that I really think we need to think about the communities. The people, the stories, and the communities that are at the heart of all the music we listen to.

Correspondent: Well, I agree with you Kiese. But I’m wondering what is the acceptable level of cultural engagement that would actually allow the South to be understood and to be properly respected versus the reality of people wanting to have something in the background. I mean, is it reasonable to expect people to have that level of engagement? Much as I would also love to see that!

Laymon: I mean, it’s not reasonable to expect. It’s reasonable to encourage. And it’s reasonable to ask people to think more about from whence the music they listen to comes.

(Loops for this program provided by Kristijann, 40A, kristijann, Reed1415, and ShortBusMusic.)

The Bat Segundo Show #513: Kiese Laymon (Download MP3)