(This is the fourteenth entry in the The Modern Library Reading Challenge, an ambitious project to read the entire Modern Library from #100 to #1. Previous entry: The Call of the Wild)

I am fairly certain that I found The Old Wives’ Tale compelling for reasons that Arnold Bennett did not intend. After my great excitement with Jack London, Bennett was something of a letdown, reading more like fossilized culch than a lively adventure from the 20th century, although I experienced a great deal of pleasure as characters began to die and as they became needlessly blamed for other deaths. Consider the manner in which Sophia, assigned to watch over her bedridden father, sneaks away for a few minutes to chat with the strapping Gerald Scales. When she returns, something terribly odd occurs:

I am fairly certain that I found The Old Wives’ Tale compelling for reasons that Arnold Bennett did not intend. After my great excitement with Jack London, Bennett was something of a letdown, reading more like fossilized culch than a lively adventure from the 20th century, although I experienced a great deal of pleasure as characters began to die and as they became needlessly blamed for other deaths. Consider the manner in which Sophia, assigned to watch over her bedridden father, sneaks away for a few minutes to chat with the strapping Gerald Scales. When she returns, something terribly odd occurs:

After having been unceasingly watched for fourteen years, he had, with an invalid’s natural perverseness, taken advantage of Sophia’s brief dereliction to expire. Say what you will, amid Sophia’s horror, and her terrible grief and shame, she had visitings of the idea: he did it on purpose!

As I continued to push through this 600 page novel, surprised by such lively spurts written in a mode I initially appraised as kitschy, there was a part of me that longed for the invention of time travel. I might roll a joint and get it into Bennett’s hands before he banged out another overly serious manuscript. His eccentricities, however, were also part of the charm. I must confess that I couldn’t quite shake Bennett.

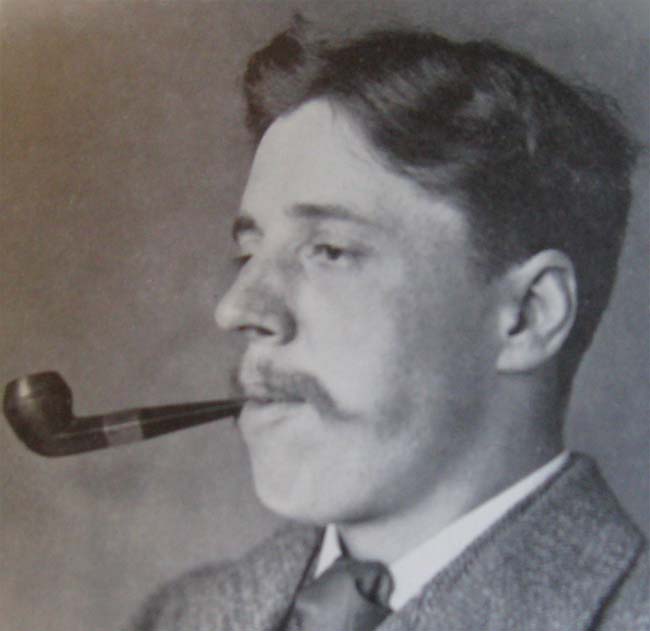

Bennett was hot shit at one point in time. I suspect his inclusion on the Modern Library list involves some guilt over his swift fall from grace. In 1923, Virginia Woolf got nasty with an essay entitled “Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown”: “he is trying to hypnotize us into the belief that, because he has made a house, there must be a person living there.” And many seemed to believe her. The literary critic FR Leavis dismissed Bennett in a sentence. The situation became so desperate that Margaret Drabble felt compelled to publish an appreciative 400 page Bennett biography in 1974.

I asked several literary friends if they had read Bennett. But only one had. And this friend made strong suggestions that Anna of the Five Towns was one of the more dispiriting reads in her formative years. I was roundly rebuked for daring to mention Bennett, the name as ancient and as displeasing to her ears as Linda Ronstadt, and was banned from discussing literary matters with my friend for a week. It’s very possible that I’m one of the few Americans under the age of 40 who has actually finished one of Bennett’s novels. (Apparently, I am not the first to raise this observation. Shortly after drafting this essay, I discovered that Wendy Lesser, writing in The New York Times in 1997, had also pointed out Bennett’s stunning precipitation. Fourteen years later, the Bennett situation is considerably worse.)

In recent years, Bennett has found a few (still living) defenders in Drabble, Francine Prose, and Philip Hensher. And while two of these boosters can be rightly praised as skilled novelists, by all reports, this collective humor-impaired trio cannot be said to be especially vivacious at social gatherings. That’s part of the problem. To get Bennett, you have to take him somewhat seriously. And that means abdicating a healthy skepticism deeply valued by any freethinker who grew up in a post-Nixon or a post-Thatcher world. These days, Arnold Bennett is best known for an omelette recipe established at the Savoy. It’s worth observing that Bennett did not come up with the recipe. He was too busy writing a novel. There are certainly worse fates for an author. But despite my gripes, I still believe Bennett deserves more than a mere legacy of haddock and peppercorns.

The Old Wives’ Tale is a strange novel, imperious and engaging at times, but I cannot call it a classic — despite its admirable narrative ambition in tracking two sisters, Sophia and Constance Baines, and their families from youth to old age. It is plagued by inhebetating verbosity (“The horror of what had occurred did not instantly take full possession of them, because the power of credence, of imaginatively realizing a supreme event, whether of great grief or of great happiness, is ridiculously finite”). It feels the need to bully the reader into excitement with obnoxious exclamation marks (“This was what he had brought her to, then! The horrors of the night, of the dawn, and of the morning! Ineffable suffering and humiliation, anguish and torture that could never be forgotten!”). It is often condescending towards its characters, using bizarre interrogatory to suggest feeling (“But why, when nearly three months had elapsed after her father’s death, had she spent more and more time in the shop, secretly aflame with expectancy?”).

There is something needlessly systematic and almost Asperger’s-like in Bennett’s fixations. Here is Bennett describing the inner life of Constance’s son:

He had apparently finished his home-lessons. The books were pushed aside, and he was sketching in lead-pencil on a drawing block. To the right of the fireplace, over the sofa, there hung an engraving after Landseer, showing a lonely stag paddling into a lake The stag at eve had drunk or was about to drink his fill, and Cyril was copying him. He had already indicated a flight of birds in the middle distance; vague birds on the wing being easier than detailed stags, he had begun with the birds.

Bennett is more interested in positioning objects rather than being explicit about what his characters feel. His fixation on external imagery prevents him from contending with emotions. And this inferential approach does have its drawbacks. Even in describing the engraving, Bennett isn’t quite sure: “had drunk or was about to drink his fill.” Shortly after this moment, Cyril feels his mother’s hand on his shoulder and, before he replies, Bennett writes: “Before speaking, Cyril gazed up at the picture with a frowning, busy expression, and then replied in an absent-minded voice.” Frowning, busy expression? My mind drew uncomfortable parallels with the autistic passages contained in Tao Lin’s Richard Yates. One could make the argument that Bennett’s superficial imagery reflects both Cyril’s transformation into a young artist or the overall shift from bucolic business to a more modern age. Yet this aesthetic approach is hardly confined to Cyril. Of one of Sophia’s clients in France: “There was a self-conscious look in his eye.” Near novel’s end, Bennett even makes a big show of how characters look at others: “Peel-Swynnerton had just time to notice that she was handsome and pale, and that her hair was black, and that she was gone again, followed by a clipped poodle that accompanied her.” Considering these odd emphases and the sweeping melodramatic statements contained elsewhere in the book, it became necessary to investigate the man further.

Arnold Bennett began writing The Old Wives’ Tale on October 8, 1907. We know this because he wasted no time marking the notches in his journal:

Yesterday I began The Old Wives’ Tale. I wrote 350 words yesterday afternoon and 900 this morning. I felt less self-conscious than I usually do in beginning a novel. In order to find a clear 3 hours for it every morning I have had to make a time-table, getting out of bed earlier and lunching later.

The next day (October 10, 1907), Bennett offers this exacting news, worthy of Trollope or a chartered accountant: “I walked 4 miles between 8:30 and 9:30, and then wrote 1,000 words of the novel.”

Bennett would finish his novel less than a year later, noting on August 30, 1908: “Finished The Old Wives’ Tale at 11:30 A.M. today. 200,000 words. Now I can begin to keep this journal again.”

Bennett was indeed a man of his word. The volume I am presently consulting from, which contains all of Bennett’s journal entries, is more than 1,000 pages. While assembling this essay over several days, I have been on the lookout for a cockroach, hoping to test the density of Bennett’s private thoughts against a very 21st century dilemma. Unfortunately, the apartment is clean, the exterminator who last doused the place (along with my own independent boric appliqué) was too efficient, and I have not seen any insect life in the order of Blattaria for many weeks. Now I can begin to write this essay again.

As Bennett was working on The Old Wives’ Tale, he worked with an industry that might put Joyce Carol Oates to shame. He wrote two short novels (Helen of the High Road and Buried Alive), any number of articles and short stories, a scenario, a play, and a few popular works of reductionist philosophy (throughout his life, Bennett was a one man self-help book factory, writing such prescriptive pabulum as How to Live on 24 Hours a Day and Self and Self-Management; he even had the temerity to argue that men were superior to women). As he was to explain in an April 9, 1908 journal entry:

Habit of work is growing on me. I could get into the way of giving to my desk as a man goes to whiskey, or rather to chloral. Now that I have finished all my odd jobs and have nothing to do but 10,000 words of novel a week and two articles a week, I feel quite lost, and at once begin to think without effort, of ideas fora new novel. My instinct is to multiply books and articles and plays. I constantly gloat over the number of words I have written in a given period.

One curious quality about this period is Bennett’s reticence to name-check his fetching French wife Marguerite. I should hasten to add that Bennett’s “habit of work” came only a few months after his marriage. Bennett does register that he walked with his wife in the pouring rain on October 16, 1907, but he is more devoted to discussing how he enjoys “splashing waterproof boots into deep puddles” than Marguerite’s feelings on the matter. When Marguerite does show up in Bennett’s journal, it is mostly through “we” rather than “Oui!” And even then, Bennett is more driven by his inner “I” than any subtle references to Marguerite’s enticing third eye. By January 4, 1908, he is preoccupied by what he misinterprets as “unconscious and honest sexuality” from a Scottish woman in a London hotel.

I mention Bennett’s myopic matrimony not because I want to gossip about an English novelist who has been dead for a good eighty years (well, that’s not entirely true; on the other hand, since Bennett was writing a column of book gossip for New Age under a pseudonym during the same period, perhaps I am unintentionally avenging his targets, even though they are now all dead and have long stopped caring), but because his treatment of Marguerite is remarkably similar to the transactional manner that salesman Samuel Povey treats Constance Baines after they are married in The Old Wives’ Tale:

The basis of this contentment was the fact that she and Samuel comprehended and esteemed each other, and made allowances for each other. Their characters had been tested and had stood the test. Affection, love, was not to them a salient phenomenon in their relations. Habit had inevitably dulled its glitter.

What does a reader do with Arnold Bennett in 2011? Bennett undoubtedly had the stuff to stir the reader, but it’s difficult to let some of his more impetuous ideas about human behavior slide. This was a weakness cited by his most ardent defenders. Even Rebecca West was to confess that Bennett struck her “as being one of the most observant and unobservant persons I have ever known. He would remember the order of the shops in an unimportant street in a foreign city for years, but he was curiously blind about human beings. He would know a man and a woman for years and see them constantly without realizing that they were engaged in a tragical love affair; he could meet a man shaken by a recent bereavement and notice nothing unusual about him til he was told.”

Yet despite Bennett’s obvious blind spots, I feel a charitable impulse for the man. Few of today’s novelists are willing to write in such a reckless yet revealing manner. Were he working today, Bennett’s work would be rent in an MFA minute. But without this rampant rashness, Bennett would not have kept up his voice.

Next Up: E.L. Doctorow’s Ragtime!