(This is the tenth entry in the The Modern Library Reading Challenge, an ambitious project to read the entire Modern Library from #100 to #1. Previous entry: Ironweed)

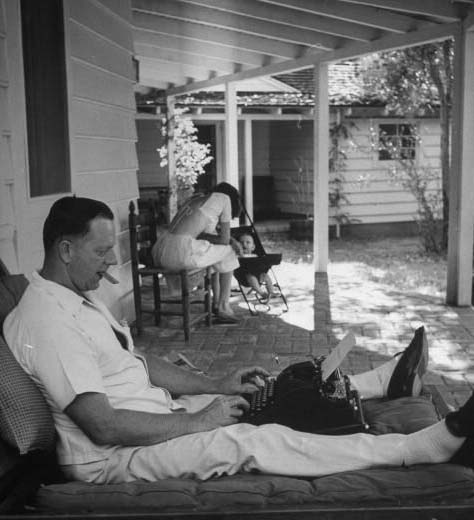

Like many great writers of the 20th century, Erskine Caldwell experienced difficulties keeping his dick in his pants. While such bulging foibles aren’t normally the stuff of pertinent consideration, Erskine Caldwell Reconsidered (edited by Edwin T. Arnold and published by the University Press of Mississippi) is the rare academic volume offering a partially persuasive case that Caldwell’s philandering was one throbbing element of the creative package.

Like many great writers of the 20th century, Erskine Caldwell experienced difficulties keeping his dick in his pants. While such bulging foibles aren’t normally the stuff of pertinent consideration, Erskine Caldwell Reconsidered (edited by Edwin T. Arnold and published by the University Press of Mississippi) is the rare academic volume offering a partially persuasive case that Caldwell’s philandering was one throbbing element of the creative package.

In an essay titled “Caldwell’s Women,” Harvey L. Klevar writes, “During the first decade of his career — during the period he was married to Helen — he published quality novels and stories enough to satisfy a lifetime’s quota for an average writer.” Helen Caldwell Cushman, Erskine’s first wife, didn’t just correct Erskine’s mistakes and critique and type his fiction. She apparently allowed Erskine to carry on extramarital affairs, with the family living in near destitution as Erskine plugged away. How does Klevar know all this? Well, in the same volume, Klevar scored an interview with Helen, digging up considerable dirt. On their first date, Erskine told Helen, “I’d like to knock you in the head with a rock and go to bed with you.” As pickup lines go, that’s somewhat audacious for the early 1920s. Yet Helen managed to stick around. Erskine’s effrontery carried on into their wedding night, when Erskine took Helen to five burlesque shows. Years into the marriage, Erskine’s reliance on Helen had reached remarkable heights:

I used to cut his work. I used to cut through with a big blue pencil. And I corrected his errors. When he was in the throes of creation, shall we call it, he was completely inapproachable, and nobody was allowed to make any noise in this house. And don’t think that was easy, with two young children. I had to keep them out of the way. He wrote very painfully and was possessed to write. He had this internal compulsion. And I was truly interested in his work or I would have left him long, long before.

Many floundering marriages squeeze in a few additional years because of money or children or tax advantages or a capitulation to religious hypocrisy. But I was amazed that Helen suffered Erskine’s cavalier caprices simply because she was curious about his writing. It’s a testament to either Erskine’s wild originality or Helen’s supreme patience.

Klevar also reports in his book-length biography that Caldwell started work on his first novel, Tobacco Road, not long after Helen’s father died, just after Christmas 1930. It’s also worth noting that Caldwell informed legendary Scribner’s editor Maxwell Perkins that he was “trying to get a new book started,” only to finish the novel in rough draft less than three months later. On May 4, 1931, Perkins received the manuscript, a little more than two weeks after Caldwell finished the rough draft. Was Helen instrumental in getting the book up to speed in such a short time? Perkins would later reply, “I’ll tell you plainly that I think myself [Tobacco Road] is well nigh perfect within its limits.” Another biography by Dan B. Miller suggests that Caldwell began writing Tobacco Road “six months before in California, and completed the actual writing in only three months.” On the other hand, Miller also writes that, despite Helen trimming “a bit here and there,” “the bulk of the novel remained as Caldwell had originally written it.”

I bring up the salacious details not to impugn or slander Erskine Caldwell, although there are many reasons for austere moralists to disapprove of his life choices (in Erskine’s defense, he would stay with his fourth and final wife Virginia — initially his editorial assistant and secretary — for close to thirty years). One must take great care to separate the art from the artist. Yet Caldwell’s fiction, with its truths about human perversity rooted in the libidinal and the louche, often resonates so strongly that one cannot help but consider these personal circumstances.

I will say that I’ve enjoyed Erskine Caldwell’s writing a great deal ever since I first read his salacious short stories (along with Cheever, de Maupssant, Maugham, and many others) as an aimless yet endlessly curious undergrad reading books while working evening and graveyard shifts as a desk clerk at a halfway house in the Tenderloin. When you’re a shy kid scrutinizing and buzzing in recovering heroin addicts and former alcoholics and ex-prostitutes and sundry streetwise fulminators, you become more willing to give people a second chance. Caldwell’s outlandish tales, especially when read at 3AM, were helpful vessels for this raucous world.

Yet for some reason (likely laziness or obliviousness), I never got around to reading Tobacco Road until a few weeks ago. I hadn’t read Caldwell in recent years, mainly because I have resisted revisiting authors who meant much to me as a young man. The profound insights one purports to detect at twenty are silly and superficial when one edges closer to forty.

Still, I was pleasantly surprised to enjoy Tobacco Road as much as I did. This is a rare novel that not only gets the vernacular exact, but that forces an audience outside this world to confront its own inherent prejudices about the impoverished. (When Tobacco Road was turned into a play by Jack Kirkland — the 15th longest running Broadway show in history — did its success have more to do with New York audiences laughing at their own biases about the seemingly backward or the overt sexuality? Caldwell’s most lucid answer on the subject came from a 1941 interview in The Washington Star: “When people laugh at the antics of Jeeter Lester, they’re only trying to cover up their feelings. They see what they might sink to.”)

Five pages into the book, Lov Bensey, just after walking seven and a half miles with a sack of turnips on his back (no convenience stores in Depression era Georgia, of course) and just after complaining about his twelve-year-old wife not sleeping with him, is already “thinking about taking some plow-lines and tying Pearl in the bed at night. He had tried everything he could think of so far, except force, and he was still determined to make her act as he thought a wife should.” I love how Caldwell orphans the phrase “except force” in commas, suggesting that there’s another level to Lov’s ruminations. What makes this situation perversely funny is how Lov seeks advice from his father-in-law Jeeter Lester before going ahead with this plan. He requires confirmation from another that this terrible idea is terrible.

While it’s certainly true that we all possess terrible ideas, if you subscribe to any religious or philosophical ideas of universal enlightenment, you’re probably inclined to believe that there is a common goodness within every soul which repairs these base instincts. This essential goodness generates remorse, reconsideration, penitence, and numerous other feelings in response to previous actions.

The Lester family contains seventeen kids (at least one of them not sired by Jeeter) who have all occupied the ramshackle environs of Tobacco Road and have largely stuck it out waiting to be married off. When the aptly named Lov shows up at the beginning of Tobacco Road to complain about Pearl, there are only two kids left: the harelipped Ellie May and the baseball thumping and car horn blasting Dude. (Physical infirmities abound in this novel. When Bessie Rice shows up later, tricking Dude into a shotgun wedding without the premarital fumbling, her underdeveloped and boneless nose is compared to “looking down the end of a double-barrel shotgun.”)

Escape would seem to be the only option for the Lester kids. Yet in fleeing this poverty, do they not become as sneering in their own way as the judgmental northern audiences reading this book? We learn that the oldest child, Tom, has become a successful cross-tie contractor “at a place about twenty miles away.” Later, when members of the family attempt to pay Tom a visit in Burke County, Tom wants nothing to do with them. Upon hearing this news, Jeeter repeats the phrase, “That sure don’t sound like Tom talking,” almost as if it’s a curative mantra to help one cope with an unforgiving reality. Another child, Lizzie Belle, has fled to a cotton mill, but “had not said which one she was going to work in.”

Are these characters good in some way? Have the Lesters developed any standards approximating some form of enlightenment? These questions of civilization — the brutal northern metric Caldwell passes along uncomfortably to the reader — hardly matter when these people are so impoverished. Especially when the impoverishment hinges upon how they believe the world operates (rather than how it really operates) and how capitalism has exploited them. Unable to raise a profitable cotton crop and denied the credit to purchase guano and seed-cotton, we learn that Jeeter has been forced to take a high-interest loan where it’s impossible for him to get back into the black. The financial situation sounds eerily similar to predatory lending during the recent subprime crisis:

The interest on the loan amounted to three per cent a month to start with, and at the end of ten months he had been charged thirty per cent, and on top of that another thirty per cent on the unpaid interest. Then to make sure that the loan was fully protected, Jeeter had to pay the sum of fifty dollars. He could never understand why he had to pay that, and the company did not undertake to explain it to him. when he had asked what the fifty dollars was meant to cover, he was told that it was merely the fee for making the loan….Seven dollars for a year’s labor did not seem to him a fair portion of the proceeds from the cotton, especially as he had done all the work, and had furnished the land and mule, too.

Jeeter still believes that he can get the farm back, even though he has sold off nearly every possession. And it is this tragicomic belief which sustains the Lester legacy, even after death and tragedy, in the book’s final paragraph. Should the Lesters, however repugnant they are perceived, be condemned because they have aspirations? This is a difficult question for elitists to swallow. Even the seemingly progressive-minded Kenneth White, writing in the July 16, 1932 issue of The Nation, complained, “There is nothing sentimental, for example, about Jeeter’s lyrical speeches of complaint, for everything is complained about. The error of the last words of the book is the error of dropping the comic method to point a moral.” What White failed to understand was that the comic, the sentimental, and the moral exist simultaneously in Caldwell’s novel. Judging by some of the surprisingly harsh reactions to Tobacco Road on Goodreads (“it seems like we were meant to laugh at the horrible people doing stupid things and making disastrous decisions, but what’s the fun in that?” or “I was horrified at what I perceived Caldwell was trying to do: get us to laugh at abject poverty, ignorance, and low down misery.”), it would appear that people remain just as uncomfortable contending with these blended emotions nearly eight decades after the book’s publication.

Caldwell is careful to demonstrate that surviving based on how one thinks isn’t confined to the low-class Lesters. When Bessie Rice cajoles Dude Lester into marrying her, bribing the young Dude with the purchase of a car with nearly the total savings of her recently departed husband, the Clerk asks the couple how they intend to support each other. “Is that in the law, too?” asks Bessie. “Well, no,” replies the Clerk. “The law doesn’t require that question, but I thought I’d like to know about it myself.”

Does the answer to one simple question offer the smoking gun? People, even the ones we frown upon, are more complicated than this. Should we judge Erskine Caldwell on his adultery or the Lesters on their apparent atavism? If all of us remain judgmental to some degree, believing we know or assuming we are entitled to know, perhaps all of us occupy some form of Tobacco Road.