[EDITOR’S NOTE: On March 22, 2013, I set out on an eighteen mile “trial walk” from the top tip of Manhattan to Sleepy Hollow, New York, to serve as a preview for what I plan to generate on a regular basis with Ed Walks, a 3,000 mile cross-country journey from Brooklyn to San Francisco scheduled to start on May 15, 2013. It will involve an elaborate oral history and real-time reporting carried out across twelve states over six months. But the Ed Walks project requires financial resources. And it won’t happen if we can’t raise all the funds. But we now have an Indiegogo campaign in place to make this happen. If you would like to see more adventures in states beyond New York, please donate to the project. And if you can’t donate, please spread the word to others who can. Thank you!]

Other Trial Walks:

2. A Walk from Brooklyn to Garden City (Part One and Part Two)

3. A Walk from Staten Island to Edison Park (Part One and Part Two)

The Broadway Bridge rumbled hard with tardy cars hoping to beat that dreaded moment when the lift raised for a big boat hauling cargo across the Harlem River, tying up traffic into a time-consuming knot that no sailor could unravel at gunpoint. On the whole, this was a reasonable bridge, agreeable and unassuming, not unlike a workmanlike band following an act that bombed spectacularly on stage. You couldn’t help but like the Broadway Bridge after all the barbed wire coils and the industrial grit that came before. But I think I may have loved the bridge simply because I crossed it on foot.

I was walking across to meet Lisa Peet, a good soul with a wily mane and a knowing glint who had kindly agreed to be my first interview subject. We met in the Gold Mine Cafe, a former donut shop recently renovated to serve breakfast at all hours of the day. This establishment inveigled the locals with its new kitschy interior, which included a Greco ideal, his knee raised, ensnared in a vessel with a periwinkle lid. This marvelously extravagant illustration, seen only if you look to your left when you leave the joint, rightly reflected the neighborhood inconsistencies that Lisa told me about. There was also a painting of an elderly woman tempting fate with a reddish orange mass, which hung just behind the table where Lisa and I chatted:

[haiku url=”http://www.edrants.com/_mp3/trialwalk1.mp3″ title=”Conversation with Lisa Peet” ]

“No restaurants,” said Lisa of her neighborhood. “No coffee shops. No galleries. No bookstores. No nothing. There’s the Bronx Ale House, which opened up a few years ago. That’s a nice place. No takeout really. There’s Riverdale. You can get delivery from there. You have to leave if you want to do anything fun.”

I pointed to the Gold Mine Cafe’s charms, which suggested new fun in the making.

“There’s fun, but you really have to make it.”

I saw the geese after I saw the coyote statue atop a rock and the slowly thawing ice rink that needed to be deliquesced out of its misery. I saw the geese after shuffling around a memorial lawn with its grave markers parked low to the grass and American flags shooting out of the soil. I saw the geese wandering near the Van Cortlandt Park baseball diamond, not far from the big track that still attracted stubborn joggers in the morning chill, and I attempted an interview.

I spent more minutes than I care to admit slowly advancing on the icy lawn, hoping that the geese might view me as more peaceful and more inquisitive than the average human. But the geese had seen humans pull this parlor trick many times before. They squawked and they sprinted in that gangly manner that only geese can and they fluttered into the air when I pursued them beyond the specified maximum distance established by the Human-Geese Accord of 1872.

The geese did not wish to answer my inquiries concerning income inequality or human-animal relations or Katy Perry’s sartorial style. Still, I was having a good deal of fun coaxing the geese to talk with me. I opted to leave them alone and file an interview request with their publicists. I did not know that there was a bigger interview ahead in Yonkers.

The idea came when I walked into Yonkers and saw Mayor Mike Spano’s name on the city limits sign. I had never been in Yonkers before. Perhaps Mayor Spano would talk with me. I had not known that Mayor Spano had just delivered the State of the City address. In fact, I knew nothing about Yonkers politics at all.

I decided to hit City Hall.

I didn’t anticipate that Yonkers City Hall would be a fairly imposing Italianate edifice built in 1908 and situated on a rather high hill.

This did not stop me.

I walked to the side entrance and told the amicable guard that I was going to the Mayor’s Office. He seemed to believe that I knew what I was doing and directed me to the second floor. I went to the Mayor’s Office and talked with a friendly woman named Francesca. The Mayor was in Albany. I asked if there was anybody else who would talk with me, but apparently all communications people were locked in an implacable meeting. It was so quiet behind Francesca that I began to wonder if city officials were playing a long game of Spin the Bottle, perhaps over coffee and cake. I asked Francesca if she would talk with me and she said that she wasn’t authorized to do so. But she was very nice about it.

It then occurred to me that Yonkers City Hall had other floors and, quite possibly, more movers and shakers who might talk with me. Since I had gone to the trouble of walking up the rather high hill, it seemed eminently reasonable to bag the Munro.

There were a few fun-filled conversations inside the Public Works Department and the Department of Engineering, although I quickly learned that Yonkers City Hall acoustics share certain qualities with an invisibility cloak. The doors throughout the building are sturdy and loud when opened. Every lawmaker and aide knows the precise moment someone enters an office. I entered one room in search of a Yonkers booster and was alarmed to hear a man reply from his office just after I chatted with several good-natured people craning their heads out of cubicles. He had heard the whole exchange. I wondered if the man was preparing for some inevitable moment when he would overhear some vital gossip that would pull him from his chamber and into some position where he would spend the rest of his days laughing as hard as Emil Jannings.

Nearly everyone in Yonkers City Hall was kind and courteous. Maybe I was stunned because, living in New York City, I’m accustomed to city employees who give you the look of someone who wants to rip out your heart with gelid hands and watch you die. It’s also possible that city employees don’t often receive visitors or interview requests quite like this.

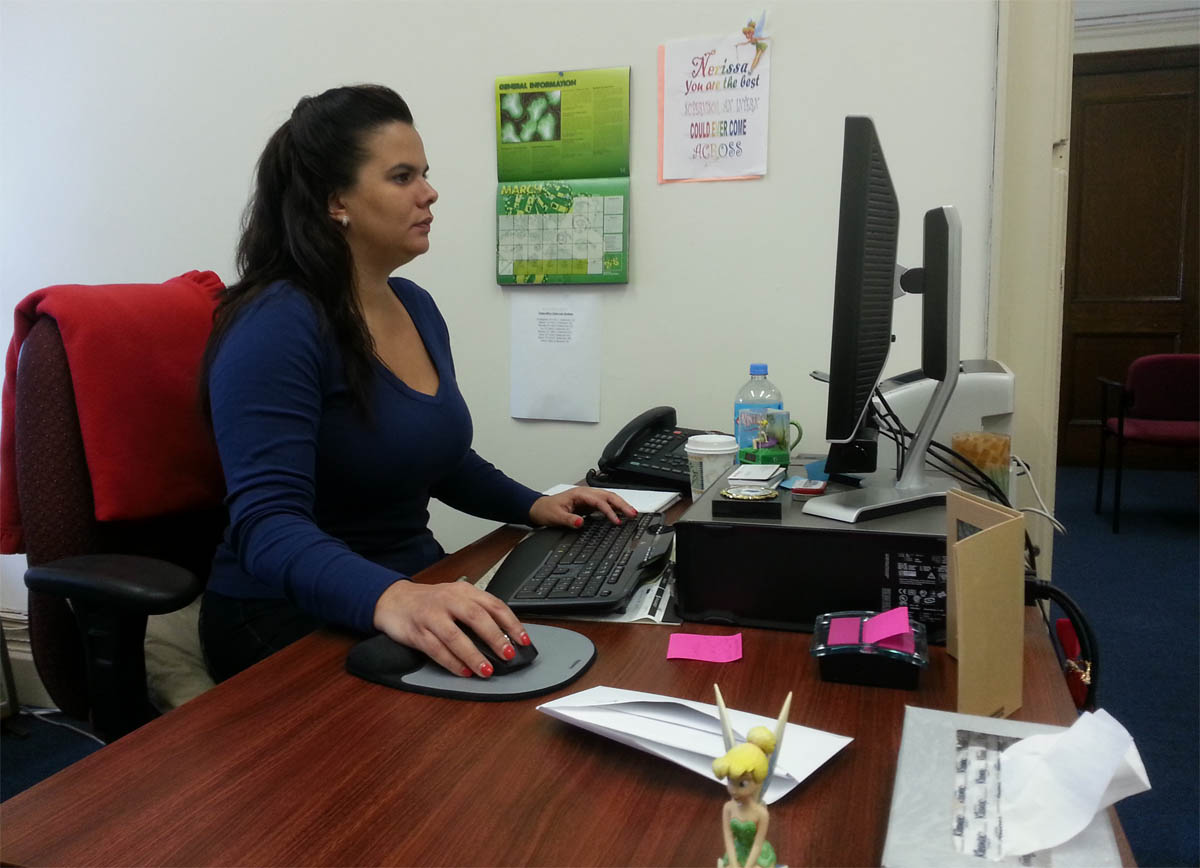

Whatever the reason, all this bonhomie led me to believe that I could talk with someone on the City Council. My journey started at one wing of the fourth floor, where administrative types were answering telephones and sealing envelopes and trying to hold the majority leader — a man named Wilson A. Terrero — to his hectic schedule. Nerissa Peña, Chief of Staff of the Yonkers City Council, was very helpful in seeking five minutes with Terrero, who was at the tail end of a vivacious meeting with two businessmen. I thanked Nerissa and told her that I would return, once I had investigated the opposite wing.

I walked to the other side of City Hall. Several people told me that there was a man named Chuck who liked to talk. Chuck was the Council President. All spoke fondly of his gregariousness. The three women working in his office. The communications guy, who name-checked Joshua Ferris’s The Unnamed when I told him about the walk. And I’m fairly certain that if I had loitered around City Hall after business hours, some wraith kicking around for decades would tell me that Chuck Lesnick is the man you need to spread the Yonkers gospel.

But Chuck wasn’t there.

It was suggested that I schedule an appointment, even though the four lovely people I talked with in Chuck’s office understood that these interviews were spontaneous.

I returned to the other wing to see if I could catch Mr. Terrero just before he was splitting for Albany. As I chatted more with Nerissa about this drop-in prospect, a calm man in a near navy sweater and a fluted gray scarf draped around his neck in a tidy coil passed along some papers for her and, eyeing the recording unit dangling across my chest with its concomitant microphone, said hello. This was Terrero himself! We came up with a plan to wait for Terrero to finish up with the two businessmen. Then I’d talk with him for five minutes before he made the two hour drive upstate.

I settled into a chair and watched the world of Yonkers politics whirl around me. The walls were white and mostly unadorned: the vagaries of city politics ensured that nobody stuck around long enough to hang a Matisse print. But Terrero had tacked his diplomas and his certificates on the wall so that any curious soul sifting through the door knew who she was dealing with. There was a Dominican flag perched behind a manilla folder and neatly arranged photos of the majority leader on a dark brown credenza: the thickest gold frame featuring Terrero in uniform, but all photos showing Terrero sharp and smooth and poised and prepared. I began to understand why he was the majority leader.

I asked Nerissa if Terrero relied almost entirely on her to keep the schedule running on time. “Yesssssssssss!!!!!” she said, the stage whisper of someone who appreciated a sharp observation.

The clock above the door pushed closer to noon.

This was now getting tight for me, especially since I still had fourteen miles to hike that day to Sleepy Hollow. So I asked Nerissa if she could chat with a few minutes.

[haiku url=”http://www.edrants.com/_mp3/trialwalk2.mp3″ title=”Conversation with Nerissa Peña” ]

Nerissa came to City Hall four years ago on the day Terrero was elected. She told me that there’s never a dull moment in City Hall. I asked Nerissa if she had any political aspirations. “Not at the moment,” she replied, which I noted was a very political answer.

Nerissa was a big fan of Tinker Bell. There was a small statuette of the famed fairy on her desk. Two interns had made a sign just before their stint was up, calling Nerissa “the best supervisor an intern could ever come across” in rainbow lettering, with Tinker Bell waving her wand in the top right corner. These days, Nerissa was sprinkling vital pixie dust for the Yonkers constituents. She said the job could get very busy, but she enjoyed the opportunity to help other people.

[haiku url=”http://www.edrants.com/_mp3/trialwalk3.mp3″ title=”Conversation with Wilson Terrero” ]

Shortly before the stroke of twelve, Terrero emerged from his office and, upon saying goodbye to the two businessmen, turned to me without missing a beat. As we sauntered slowly down the stairs, Terrero told me that while his job was technically part-time, he worked full-time to serve the community.

“There is a community out there that is in need of representation. And when I say ‘needs,’ it’s basically the Latino community, which has been underrepresented for so long.”

Despite the fact that 35% of the Yonkers population is Latino, the city had been slow in electing Latinos to the City Council. This was one of the reasons why Terrero had decided to run.

“The Party was looking for someone who had been involved in the community, who was likable and electable also. And they found me. And I said, ‘Okay.’ I went to my family. I went to the community to ask them for questions. Whether you see me as a politician now. Do you think I can do a good job?”

Last year, Terrero became the first Latino City Council Majority Leader in Yonkers. It was an unanimous vote and it’s easy to see why. Despite all the meetings (four that day) and the community events that take up Terrero’s busy calendar, he has a calm and easygoing manner. And when we hit the ground floor, many city workers clapped his shoulder with affection on their way out to lunch.

Terrero has developed this quiet patience that allows him to speak with all types of people, regardless of education and background. When I asked Terrero about the greatest nightmare he’s ever faced in his political career, he told me that he loves the job so much that the excitement of a tough vote overshadows the difficulty. He’s more interested in making things happen.

“Yesterday, we called this special meeting to vote for a project I believe is very important for the city. It’s going to create jobs. Temporary jobs, permanent jobs. And the people of the city are the ones who are going to benefit. The Teamsters are going to build that housing complex. And only five of us voted for the project. And there was a discussion about it. And at the end, some people just crossed lines and said, ‘Yes, I’m going to vote for it.’ And they did.”

His day begins at eight in the morning, when Terrero exercises and showers and prepares himself for the long day. He is a former baseball player. So he’s had some practice at this. City Council meetings can stretch into the dead of Tuesday night and often across the rest of the week. And when your time is devoured by talks and votes, you need every bit of energy you can to keep the flame alive.

I had spent more time in Yonkers than planned and there was still the matter of lunch. I walked north on Warburton Avenue, which ran along the river and the rails. I passed schools and churches and houses increasingly labeled “private.” I passed riverside dog runs and attracted barks from playful canines.

The plan was to stop at Hastings-on-Hudson and grab something to eat there. But I became so caught up in my walking rhythm, taking in the beautiful quietude of creeks burbling into the Hudson and the wind lapping at the surviving vegetation, that I overshot Hastings entirely and ended up in a village called Dobbs Ferry.

I settled into a booth at Doubleday’s, the kind of place where a man in late middle age sits at a bar and orders a lemonade and vodka at 2:00 in the afternoon. There were many TVs blaring sports, with a slight echolalia among sets televising the same feed. None of this stopped the talk from flowing like a loose tap.

“We did fall in love with each other, but we didn’t have much of a choice. Forty years later…”

This expansive establishment was arranged like a triptych: a restaurant to the south, the bar forming the central hub, and an open room to the north for overflow on busy nights. There was talk of football pools and objects flying up from the road and scratching the insides of eyes. This was a place where you could melt away hours of your life and not even know it. I would have stayed if I did not have an appointment with Washington Irving.

I had only a few hours left of daylight and six miles left before Sleepy Hollow. One of the big surprises was running into Villa Lewaro, the home of Madam C.J. Walker, the first self-made African American millionaire. Madam Walker had made her mark with a sulfur-enhanced shampoo and donated considerable money to the YMCA and the NAACP. She even saved Anacostia, the home of Frederick Douglass. She lived in the house in 1917 and taught many other women to run their own businesses.

I knew Andrew Carnegie was buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, which was where I was heading. Given my Indiegogo campaign, it was odd how my trial walk had me running into very charitable people. Maybe Carnegie could use a dramatic audio reading about steel. I considered hitting these two up for donations. But then I remembered that Walker and Carnegie were dead, which probably prohibited them from helping me.

Not long after Villa Lewaro, I hit the Washington Irving Memorial on the edge of Tarrytown. There were increasing indicators that I was close to Sleepy Hollow. Washington Irving School. A housing project named after Washington Irving. Washington Irving appeared to have more places named after him in Tarrytown than Walt Whitman did in Brooklyn. I wondered if culture would be this kind to its literary figures fifty years from now. Would we see Joyce Carol Oates School or William Gass School? Or would tomorrow’s educational institutions be named after the likes of Brett Ratner or Sergey Brin?

“Over a deep black part of the stream, not far from the church, was formerly thrown a wooden bridge; the road that led to it, and the bridge itself, were thickly shaded by overhanging trees, which cast a gloom about it, even in the daytime; but occasioned a fearful darkness at night. This was one of the favorite haunts of the headless horseman; and the place where he was most frequently encountered.” — Washington Irving, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”

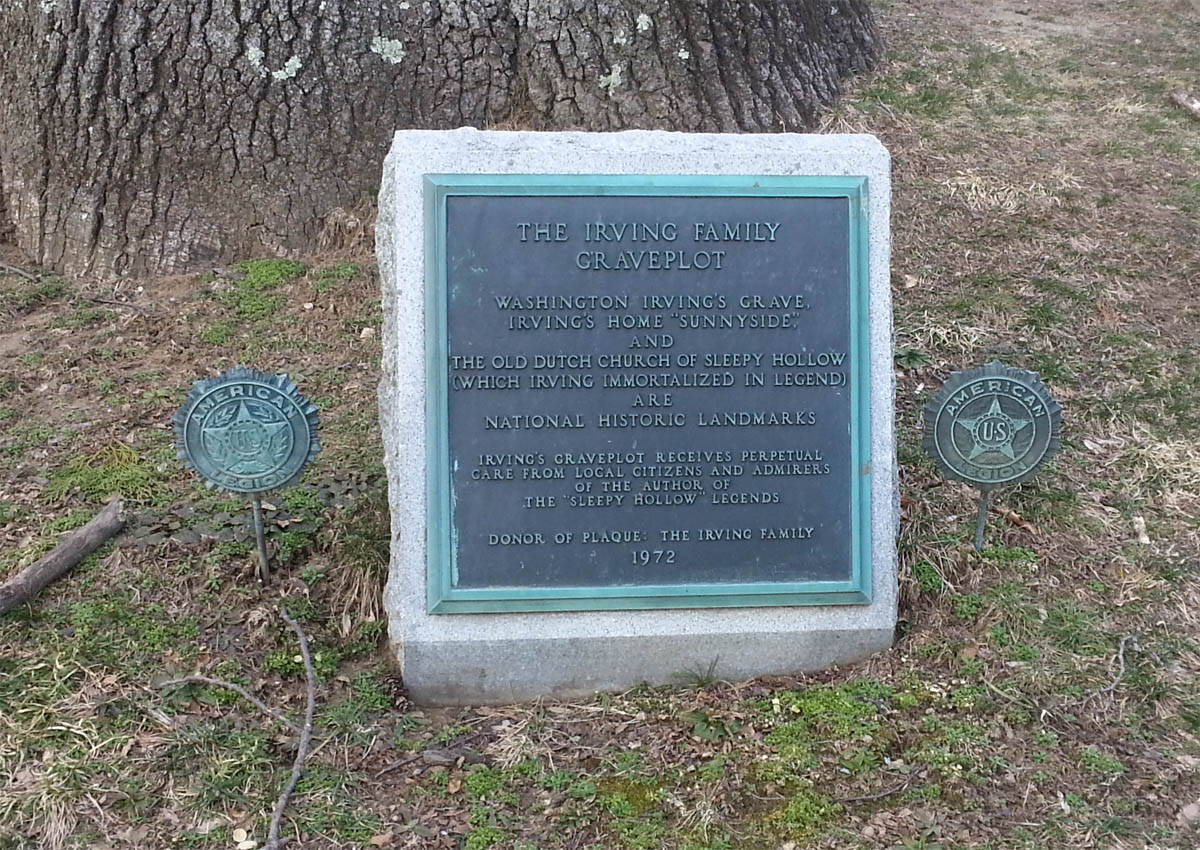

After eighteen miles of walking, I arrived in Sleepy Hollow at around 5:00 PM, where I was overjoyed to discover the Headless Horseman Bridge or, rather, the place where it had once stood. But given how Irving had described it in the original story as “formerly thrown,” I wondered if had ever truly existed. I didn’t have a horse, but I dropped my head beneath my shirt and walked across the bridge headless. A car horn beeped back with approval. Then I turned my attention to the cemetery, the final destination of my journey, only to find this:

The gates were locked. Sleepy Hollow Cemetery had closed only a half hour before I arrived.

This was surely the most crushing setback I have ever experienced as a walker. I had walked so long and hard to get here. I had two choices: I could turn around and frown my sorrows into a beer or I could find a way in.

You can probably guess the option I chose. I rationalized my decision by pointing out that I was no common trespasser. These were extenuating circumstances! Nobody in American history has ever walked eighteen miles to check out a great cemetery. I found an open area and walked in.

I was surrounded by numerous tombstones: glorious gray slabs with carefully carved names that had been eaten away by the elements over the centuries. There were families now long forgotten and many of the plots were quite strange.

Then there was the Irving family:

With the sun falling fast, I flailed around the graveyard, seeking Andrew Carnegie’s marker, but I couldn’t find it. I should note that I became so exuberant about this magnificent cemetery that I was live tweeting my finds, openly using the terms “Sleepy Hollow” and “Sleepy Hollow Cemetery.” I am almost certain that these announcements of modest interloping led to what happened next.

In an effort to track down Carnegie’s grave, I tried searching online for a cemetery map with my phone. I was unsuccessful, but I did learn that physical maps existed close to the gates. I grabbed a map from the entrance, long after I had informed The Man on Twitter of my activities. Then I saw a white minivan roll up to the cemetery gates, with the driver making a move to unlock them. I decided to hightail it back to the way in. With the gate open, I saw the minivan roll slowly my way. On my way back, I heard two loud siren blurts near the Headless Horseman Bridge.

I knew that if I continued that way, I’d probably be grabbed by the cops. So I found a fence and I hopped over, landing into an unmaintained sidewalk. I heard another blurt from the police just south of me. So I walked across North Broadway and made my escape.

My eighteen mile walk had ended in a modest chase. I had gone from the noble heights of Yonkers City Hall to the unanticipated lows of being on the lam.

It was time to grab a beer.

[EDITOR’S NOTE: If you would like to see more adventures and investigation into our nation like this and regularly offered over the course of six months, please donate to the Indiegogo campaign.]

Anderson: If we can just get a little bit more of our own buying power to be recycled in our own communities, maybe we can bring those jobs numbers up. The other number is that black businesses are, by far, the greatest private employer of black people. Black unemployment, we know, is three times the national average of our white counterparts. Highest among any ethnic group. And in some places like Birmingham and Cleveland, we’re at black unemployment like 15, 16%. So maybe if we start supporting more black businesses that employ black people, we can stop black unemployment. So it was really just about making sure the conversation about the black situation in America is thorough and comprehensive. We can’t just keep talking about black unemployment and then not talk about black buying power and the fact that black businesses employ people and that none of our buying power is going to black businesses. So the numbers that we depended on — to get back to your question — you know, it’s just kind of known in our community how we don’t support each other. How if you walk up and down the street in a black neighborhood, none of the businesses there are black-owned except for funeral parlors, barber shops, and the braid salons. It’s just kind of known that most of the products on the shelves, none of the retailers in our community, none of the franchises are black. So we just kind of know that and joke about it. It hurts, but we just accept it. But it’s so hard to find data to bear that out. My roommate jokes about it. But we did find an interesting study — I think it was an economist, John Wray. Who did a study based out of DC that proved this horrible statistic about how long the dollar lives in different ethnic communities.* This statistic is used a lot in this conversation when people

Anderson: If we can just get a little bit more of our own buying power to be recycled in our own communities, maybe we can bring those jobs numbers up. The other number is that black businesses are, by far, the greatest private employer of black people. Black unemployment, we know, is three times the national average of our white counterparts. Highest among any ethnic group. And in some places like Birmingham and Cleveland, we’re at black unemployment like 15, 16%. So maybe if we start supporting more black businesses that employ black people, we can stop black unemployment. So it was really just about making sure the conversation about the black situation in America is thorough and comprehensive. We can’t just keep talking about black unemployment and then not talk about black buying power and the fact that black businesses employ people and that none of our buying power is going to black businesses. So the numbers that we depended on — to get back to your question — you know, it’s just kind of known in our community how we don’t support each other. How if you walk up and down the street in a black neighborhood, none of the businesses there are black-owned except for funeral parlors, barber shops, and the braid salons. It’s just kind of known that most of the products on the shelves, none of the retailers in our community, none of the franchises are black. So we just kind of know that and joke about it. It hurts, but we just accept it. But it’s so hard to find data to bear that out. My roommate jokes about it. But we did find an interesting study — I think it was an economist, John Wray. Who did a study based out of DC that proved this horrible statistic about how long the dollar lives in different ethnic communities.* This statistic is used a lot in this conversation when people  Correspondent: I know. No, this is all very good. And there’s a load of threads to start from here. Actually, I’m sure you’re familiar —

Correspondent: I know. No, this is all very good. And there’s a load of threads to start from here. Actually, I’m sure you’re familiar —  Anderson: The white man Charlie. But anyway, the book is really — if I’m yelling at anyone, it’s at black consumers. Because there’s a lot of history here that contributes to the bad situation we’re in. I’ll be really quick. A lot of it has to do with integration. Of course, we love what integration did in this country. Of course, we fought for it. But it had some really negative impact. Some deleterious impact into the black economy, if you will. Because we’re forced to, because we’re segregated, we built up our own businesses. We had a strong sense of entrepreneurship in our community. And we recycled our wealth. So that was just the fact. That was the way it was. And the University of Wisconsin

Anderson: The white man Charlie. But anyway, the book is really — if I’m yelling at anyone, it’s at black consumers. Because there’s a lot of history here that contributes to the bad situation we’re in. I’ll be really quick. A lot of it has to do with integration. Of course, we love what integration did in this country. Of course, we fought for it. But it had some really negative impact. Some deleterious impact into the black economy, if you will. Because we’re forced to, because we’re segregated, we built up our own businesses. We had a strong sense of entrepreneurship in our community. And we recycled our wealth. So that was just the fact. That was the way it was. And the University of Wisconsin  Anderson: Right. And this is a huge point that I have to contend with when I push this supply diversity franchise rediversity message into the community. And here’s how it goes when I’m talking to black folk who I’m trying to get to support black businesses. It should not be that tough of a fight, but it is. When I say this to them, they come at me, generally with stuff like “Well, we tried to Karriem [Beyah]’s grocery store. He didn’t have the thing that we wanted.” Or it wasn’t like going to our Jewel, the big grocery store chain around here. Or you can go to this black franchise. But I didn’t see a bunch of black employees there. Or how do I know Quiznos is a good franchise to be supporting? So I get a bit of a challenge. Then I say, “Well, you know what? How is that? I mean, what are you doing now?” Basically, we’re just out there supporting anybody. Not thinking about what the businesses are doing for us. Polo. I mean, Polo blew the lid off of black consumers. We have black Polo parties that we have for our kids. I mean, it’s just ridiculous how addicted we are to the Polo brand. I have nothing against Polo Ralph Lauren. But I did have a friend who works writing for the CFO of Polo, and I asked her to do some research for me. She’s a conscious consumer like me. HBS grad. Very well connected in the company. And she thinks they talked with the marketing folks, the procuring folks, everybody about buyer diversity. Do you do business? How do you invest in the black community? We have so much money coming in from the black community. And their answer to me was, “Well, our label comes out of Indonesia.” And it’s unbelievable. That’s the best we can do to reciprocate the loyalty that the black community’s giving you? So it’s like, “Yeah. Maybe.” And you’re totally right about the Quiznos thing. But the first answer to them is, “But you’re supporting Polo. And it’s not like you’re stopping in support of Polo.” And I’m not saying don’t support Polo. But if you’re so discriminating with how you spend your money, there’s a lot of things that we shouldn’t be doing that we ought to be doing.

Anderson: Right. And this is a huge point that I have to contend with when I push this supply diversity franchise rediversity message into the community. And here’s how it goes when I’m talking to black folk who I’m trying to get to support black businesses. It should not be that tough of a fight, but it is. When I say this to them, they come at me, generally with stuff like “Well, we tried to Karriem [Beyah]’s grocery store. He didn’t have the thing that we wanted.” Or it wasn’t like going to our Jewel, the big grocery store chain around here. Or you can go to this black franchise. But I didn’t see a bunch of black employees there. Or how do I know Quiznos is a good franchise to be supporting? So I get a bit of a challenge. Then I say, “Well, you know what? How is that? I mean, what are you doing now?” Basically, we’re just out there supporting anybody. Not thinking about what the businesses are doing for us. Polo. I mean, Polo blew the lid off of black consumers. We have black Polo parties that we have for our kids. I mean, it’s just ridiculous how addicted we are to the Polo brand. I have nothing against Polo Ralph Lauren. But I did have a friend who works writing for the CFO of Polo, and I asked her to do some research for me. She’s a conscious consumer like me. HBS grad. Very well connected in the company. And she thinks they talked with the marketing folks, the procuring folks, everybody about buyer diversity. Do you do business? How do you invest in the black community? We have so much money coming in from the black community. And their answer to me was, “Well, our label comes out of Indonesia.” And it’s unbelievable. That’s the best we can do to reciprocate the loyalty that the black community’s giving you? So it’s like, “Yeah. Maybe.” And you’re totally right about the Quiznos thing. But the first answer to them is, “But you’re supporting Polo. And it’s not like you’re stopping in support of Polo.” And I’m not saying don’t support Polo. But if you’re so discriminating with how you spend your money, there’s a lot of things that we shouldn’t be doing that we ought to be doing.