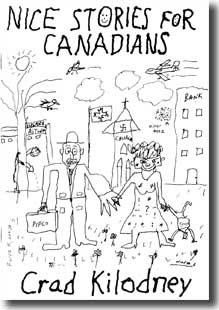

One of the writers in my 1979 “Some Young Writers I Admire” article did have a substantial, if offbeat, literary career in Candada, but as his Wikipedia entry notes, he “retired from writing in 1995, and is now self-employed as a day trader.” As he told the Toronto newspaper Eye Weekly in his final interview, “I intend to disappear totally. I already stopped writing two years ago. I will never publish another book–why should I? I’ve produced more literature than this country ever deserved.”

Yet he’s still well-known and admired by those who bought his books directly from the author in the many years he sold his self-published editions on the streets. For example, see the reminiscences of this Greece-based blogger:

Kilodney would stand on the busiest streets in Toronto with a small cardboard sign hanging from his neck. They would read

Pleasant Bedtime Reading

Putrid Scum

Slimy Degenerate Literature

Dull Stories for Average Canadians

Literature for the Brain-Dead

Worst Selling Author — Buy My Books

Rotten Canadian Literature

Albanian Chicken Stories

His face was serious, even forbidding to some people who passed by and happened to make eye contact with him. I don’t remember ever feeling intimidated by him or if I spoke to him much the first time I saw him. Soon enough, however, I knew him well enough to stand around and chat with him whenever I saw him. He would complain about how bad business was and gape stupidly at passers-by who ignored him. I remember him once droning, “Hockey books. Hockey books. Get your hockey books.”

Once, a tough-looking teenager passed by as we were talking and shot him a glance.

“You know,” I said when the kid was about five paces away, “I don’t think he’s going to mention to his friends that he saw you today.”

“Are you kidding?” Crad said. “He’s forgotten me already.”

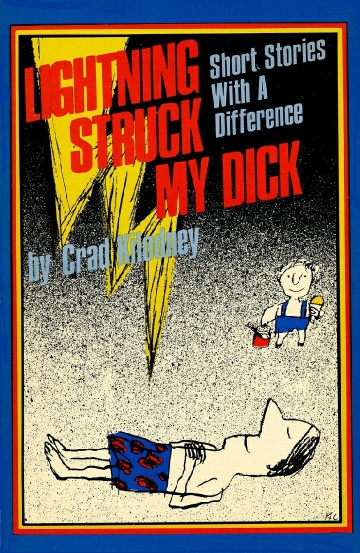

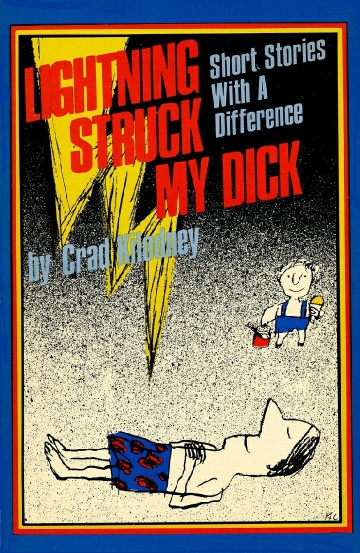

I first read something by Crad Kilodney when I was an MFA student at Brooklyn College in 1975. The fiction editor of Junction, the literary magazine of BC’s English graduate students, I found an issue in our files that began with a remarkable story, a punning, sly narrative told by a father watching his five-year-old son Dick at the beach as he muses on three topics: crabs, sand and McKinley assassin Leon Czolgosz. It ends with the narrator observing “an interesting natural phenomenon” when his child gets hit by a lightning bolt. Five years later that story, its nondescript title changed, would become the title story in Kilodney’s successful 1980 commercially-published collection, Lightning Struck My Dick.

Before that, in the 1970s, I read many of Kilodney’s wonderfully funny, weird, idiosyncratic stories (“The Hardworking Garbagemen of Cleveland,” “The Mentally Disturbed Astronomers of Cincinnati,” “Forget That Grapefruit; Here Come the Midgets”) in many literary magazines, from Rick Peabody’s Gargoyle and Ed Hogan’s Aspect to Tom Whalen’s Lowlands Review, which devoted an entire 1978 issue to a Crad Kilodney chapbook, Mental Cases.

It was through Tom that I learned the real name of Crad Kilodney and we began an intense correspondence, sending long letters back and forth several times a week between Brooklyn and Toronto. I learned that “Crad” (his identity has never been revealed and I will not do so here) was born in 1948 in Jamaica, Queens; raised on Long Island; had a degree in astronomy from the University of Houston; and moved to Canada out of disgust with Watergate and U.S. culture generally. He decided to become a writer and had an early success with the first unsolicited story accepted by The National Lampoon.

While on Long Island after college, he’d worked for a leading vanity publisher, giving him a lifelong affection for and inspiration from the crackpots who paid to have their horrendous novels and bizarre conspiracy theories and weird treatises “published” by Exposition Press. In Canada he’d had a series of miserable jobs in publishing, working as a sales rep for major publishers like McClellan and Stewart and finally ending up doing menial work in book warehouses among colleagues he considered mentally deficient.

At the first of many meetings during his annual summer visit to his grandparents’ house in Jamaica (my mouth still waters thinking of the sweet “Greek goodies” made by his grandmother, who once owned a diner), when we were both about to have short story collections come out from commercial publishers, I learned of Crad’s plan to quit work and begin selling his books on the street.

Having never in my life met such a misanthrope, I wondered why he would subject himself to a public he despised. On the other hand, he was very kind to nearly everyone he met: he spent three weeks with me in Florida one winter and when we traveled to New Orleans to teach at NOCCA in Tom’s writing program, Crad was excellent and much loved by the students. I still recall how they adored his reading of a story with about sixteen false starts, “Jap Scientologists Ate My Grandfather.”

Working on the streets of Toronto for seventeen years — often he’d stand near the Toronto Stock Exchange building — Crad lived a meager existence selling the nearly 30 little books he published under his own Charnel House imprint. (He also occasionally had a commercial book out, like Pork College from Canada’s respected Coach House Press.) His titles were often memorable: Bloodsucking Monkeys from North Tonawanda; Bang Heads Here, Suffering Bastards; Sex Slaves of the Astro-Mutants; Junior Brain Tumors in Action; Suburban Chicken-Strangling Stories; I Chewed Mrs. Ewing’s Raw Guts; Simple Stories for Idiots; Foul Pus from Dead Dogs. Ignored and ridiculed by most of Canada’s literary establishment, Crad nevertheless had for years a secret affair with an older, respected writer (she had won the prestigious Governor General’s Award) that ended only with her death.

As “The Rev. Crad Kilodney” (he was a Universal Life minister), he wrote a monthly advice column for the Canadian porn magazine Rustler, in which he answered mail from people with sexual perversions, all attributed to real-life people who’d crossed him or his friends, like the Minneapolis Tribune reviewer who called my first book “unbelievably bad.” He also had a column in Toronto’s alternative weekly Only Paper Today, “Crad Kilodney’s Vanities,” in which he reviewed horrendously awful vanity press books; later, he got Tom Whalen, me and other writers to join him in creating deliberately terrible short fiction for several volumes of his Worst Canadian Stories.

By the late ’80s, Crad had become a Canadian cult figure, beloved by many who befriended him and championed his works. A film documentary about him premiered at the 1993 Toronto Film Festival. In a 1988 prank, Crad submitted a number of stories by famous writers to the CBC Radio literary competition, many under absurd names. When the stories by Hemingway, Chekhov and others were screened out by the jury, it made a funny news story as Crad said he’d proven that the establishment could not recognize quality literature.

As his Wikipedia entry notes, in 1991 Crad was arrested for selling commercial goods without a license, “making him the only Canadian writer ever arrested for selling his own writing. At various times he kept a tape recorder with him and recorded quite a bit of bizarre byplay between himself and prospective customers; the tapes are extremely rare and are collector’s items (much as original printings of his books are). Several of his stories (such as “Henry”, featured in Girl on the Subway) are also inspired by these experiences.”

Crad and I gradually grew less close over the years. He did not want to get a computer to correspond by email. To me, his stories began to be more scatalogical (one book, a very dark one about his life on the street, was called Excrement) and to some extent racist and xenophobic. I believed he stayed too long on the streets, but what else was there for him to do?

Finally, when his grandmother and then his parents died in the mid-’90s, his inheritance allowed him to retire and concentrate on being an investor — something he’s been very successful at. He specializes in Canadian mining and energy stocks and has become quite well-known in these circles. The Toronto writer Syd Allan has set up some Crad Kilodney web pages which for a while contained monthly columns by Crad. But he’s gone from the literary scene, which has led to blog entries like Whatever happened to Crad Kilodney?

I hope one day that some publisher will revive Crad Kilodney’s literary career and republish his best stories, like “The True Story of My Dentist, Dr. Mark Litvack,” which begins:

You know how it is when you’re a writer. Everyone you know wants you to write about him. One of these days, I’ll put all of those people in one story, give each of them a few good lines to say, and that’ll be that.

However, my dentist, Dr. Mark Litvack of 1500 Bathurst St., Toronto, has finally persuaded me to devote a story to him. The fact that I have a bill outstanding since last year is not the main reason for doing so. When I find a fascinating character, I can’t help but sit down and write about him.

I’ve come to learn quite a lot about Dr. Litvack, or Mark, as I call him since we’re about the same age. He never rushes with me, because he likes to chat. Sometimes he poses questions I cannot adequately respond to when he’s working on me, but I’m sure when I grunt, he knows exactly what I intend to say. That’s the kind of rapport that one only finds between a writer and his dentist.

Before I get down to the story itself — although it’s more of a biographical sketch, I guess — I want to take a moment to tell you that a lot of my success as a writer is due to Dr. Litvack. When you have pain in your mouth or have lost a filling, you just can’t concentrate on writing nice Canadian stories. At least I can’t, and I’ll bet if you’re honest, you’ll admit you can’t either.

So I see him regularly to take care of those cavities before they get big. Usually I don’t have any because I take good care of my teeth. Dr. Litvack showed me how. He took out this giant-size plastic set of teeth and showed me the proper way to brush. I also floss, which a lot of people don’t. A lot of the confidence that comes across in my writing is really the result of good oral hygiene

Crad, we hardly knew you.