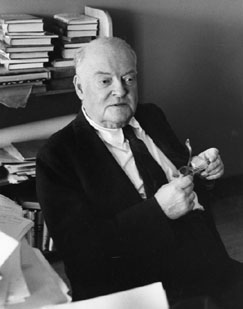

In between books I have to read for work, I’ve sneaked in a few pages of the two-volume Edmund Wilson set recently put out by the Library of America. It shouldn’t come as much of a surprise that, when not defending Hemingway against his political critics or concluding that Intruder in the Dust “contains a kind of counterblast to the anti-lynching bill and to the civil-rights plank in the Democratic platform,” the man was a bit of a douchebag. And I say this as someone who enjoys some of his literary criticism. What’s particularly surprising is how dismissive Wilson is of mysteries.

Starting with the obnoxious essay, “Why Do People Read Detective Stories?,” Wilson declares, “I got bored with the Thinking Machine and dropped him.” He dismisses two Nero Wolfe books “sketchy and skimpy” and writes of The League of Frightened Men “the solution of the mystery was not usually either fanciful of unexpected,” failing to consider the idea that a good mystery may not be about the destination, but the journey. He declares Agatha Christie’s writing “of a mawkishness and banality which seem to me literally impossible to read,” but fails to cite several specific examples, before concluding:

Starting with the obnoxious essay, “Why Do People Read Detective Stories?,” Wilson declares, “I got bored with the Thinking Machine and dropped him.” He dismisses two Nero Wolfe books “sketchy and skimpy” and writes of The League of Frightened Men “the solution of the mystery was not usually either fanciful of unexpected,” failing to consider the idea that a good mystery may not be about the destination, but the journey. He declares Agatha Christie’s writing “of a mawkishness and banality which seem to me literally impossible to read,” but fails to cite several specific examples, before concluding:

You cannot read such a book, you run through it to see the problem worked out; and you cannot become interested in the characters, because they never can be allowed an existence of their own even in a flat two dimensions but have always to be contrived so that they can seem either reliable or sinister, depending on which quarter, at the moment, is to be baited for the reader’s suspicion.

If Wilson protests the detective story so much (as he points out, T.S. Eliot and Paul Elmer More were enchanted by the form), why did he bother to write about it at all? Should not an erudite and ethical critic recuse himself when he loathes a particular form?

It gets worse. If caddish generalizations along these lines weren’t enough, he returns to the mystery subject in the essay, “Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?,” written in response to many letters that had poured in from readers hoping to set Wilson straight. He dismisses Dorothy Sanders’s The Nine Tailors, openly confessing:

I skipped a good deal of this, and found myself skipping, also, a large section of the conversations between conventional English villa characters: “Oh, here’s Hinkins with the aspidistras. People may say what they like about aspidistras, but they do go on all the year round and make a background,” etc.

Aside from the fact that Wilson, in failing to read the whole of the book, didn’t do his job properly, it never occurs to Wilson that Sayers may have been faithfully transcribing the specific manner in which people spoke or that there may actually be something to these “English village characters.” Here’s the full quote from page 57 of Dorothy Sayers’s The Nine Tailors:

“Oh, here’s Hinkins with the aspidistras. People may say what they like about aspidistras, but they do go on all the year round and make a background. That’s right, Hinkins. Six in front of this tomb and six the other side — and have you brought those big pickle-jars? They’ll do splendidly for the narcissi….”

In other words, what Wilson has conveniently omitted from his takedown is Sayers pinpointing something very specific about how everyday routine, a fundamental working class component that seems lost upon Wilson despite his Marxism, leads one to disregard the fact that someone has died. Thus, there is a purpose to this conversation.

Yet this is the man being lauded on the back cover of the Library of America volumes as “wide-ranging in his interests.”

Wilson read mysteries for the wrong reasons. He saw trash only because it was what he wanted to see. Wilson’s incompetence is a fine lesson for contemporary readers. A book should be read on its own terms, and it is a critic’s job to try and understand a book as much as she is able to, reserving judgment only when she has fully read the book and after there has been some time to masticate upon the reading experience.

I disagree with Adam Kirsch’s recent assessment that “The best critics, like the best imaginative writers, are not right or wrong — they simply, powerfully are.” A critic, like any other human being, is often wrong, particularly when approaching a book with prejudgment or a fixed notion, such as Wilson did, of a mystery merely being about whodunnit. To avoid being wrong in this way, and to simply exert one’s opinion at the time of reading, requires as much careful reading and accuracy as possible, lest a great novel be thoroughly misperceived. It requires acceptable context and supportive examples. Wilson could not do this with mysteries and, if he is to be lionized, one should be aware that, when it came to Dorothy Sayers, he was no better than Lee Siegel in his tepid reading comprehension.

Huh — I listened to an unabridged audio version of The Nine Tailors years ago on a cross-country trip, and it was clear that Sayers was writing a novel of village life that happened to be disguised as a mystery. The solution to the mystery, while ingenious (and probably groundbreaking at the time), was a secondary pleasure.

Wilson didn’t “get” Lovecraft either.

It’s probably in there at some point, but Wilson also famously hated Tolkien, calling The Fellowship of the Ring “juvenile trash.”

Come on not everyone needs to love everything Ed. Besides if literary fiction sold even close to the way mysteries and other “genres” do they wouldn’t need champions. (hah, haha) I think the snobbery of literary writers and critics (much like the snobbery of poets towards prose writing) has to do with the sense of embattlement one gets from being not widely read, not necessarily understood, generally ignored.

Wait, not everyone thinks that Tolkien is clumsy and juvenile? That is more surprising than Wilson’s correct opinion of it.

I have tried, I really tried to appreciate Wilson and I have never found him anything but a tremendous bore.

About mysteries, they ARE essentially whodunits! Or are you going against your advise that a book “should be read on its own terms”?

No, Seriously, some of us kinda like Tolkien and don’t find his insights juvenile.

Hope the failed novel about nothing in particular is coming along swimmingly.

I’m afraid it may have been Bunny Wilson’s snobbery, rather than his great essays on such topics as Dickens, Wharton, Hemingway’s misogyny, Casanova’s old age, and Joyce, that allowed him to remain a revered figure in the Fifties and Sixties. Only one side of the Left’s populist/High Culture battles of the Thirties stayed respectable after the war, at least in literature; and it wasn’t the side that welcomed Hammett and Pohl but the side that was more easily co-opted by the CIA.

You know what else? “The Wound and the Bow” is an utterly pedestrian essay, mostly comprising plot summary, that’s had a pernicious effect on the use of Disease as Metaphor.

You know, Wilson does have value: critics like Wilson help fellow snobs avoid the hack books, whether they are juvenile and clumsy, but bestsellers. It’s a brotherhood that I like. Where Wilson failed is in his judgement that a mystery has no value. He just didn’t see it as value and didn’t allow anyone else to believe they had value. He was a hammer and everything else a nail.

Ooh, can we have an essay on Stanley Edgar Hyman next?

[…] a douchebag.” To be clear on this, I wrote “the man was a bit of a douchebag” and offered an argument supporting why I felt this to be the case. Nevertheless, I will inform the editors who hire me on a professional basis that Lee Siegel has […]

Edmund Wilson incompetent? ha-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha. Then again this is the INTERNET-dummyville.

Wilson is easily the finest American critic of the 20th century. Mr. Champion helps us chart the decline of the American intellect….and his own.

Here again we see the “narcissism of small differences…” at which Mr. Champion is champ.

To paraphrase someone’s comment, Edmund Wilson’s mission was to prove that he was the only adult in the room.

heres to bunny wilson

who set the table at a roar

was best at criticism

and always managed to score

and now its po mo polemic

and writers who can’t parse

farewell to edmund and his age

alas: we’ve now just farce

Wilson is a bit of a complicated person. If he was a snob at times, it harkened back to his days as a privileged youth, going to a fine prep school and then to study under Gauss at Princeton. He read voraciously, traveled all over Europe, Russia, Canada in addition to the US. But, he had a love for the common man, despite appearing snobbish at times. Consider his in depth study of the Iroquois Indians and his genuine empathy for them. I truly believe he was also a believer in integration and that all human races are equals. I would not consider him “boorish.”

Wilson tended to get carried away by charming and good looking younger women. Perhaps Anais Nin owed him her professional career for his overly enthusiastic reviews of her early works. Also, Wilson drank too much. If you read “The Fifties” and “The Sixties” you will see his thinking is often clouded by alcohol. But, I enjoyed reading these plus “Upstate”, the “Old Stone House” and a few of his other writings. I do not think you can truly call Wilson a snob after you see how he truly enjoyed mixing with the country people who lived around his beloved Talcottville Old Stone House.

The sad thing about wilsons snotty ( self admittedly absent and incompetent criticism ) of genre’s such as mystery, horror and fantansy, is that those genres have replaced the “serious” forms of his generation. younger reasers of wilson (if there are any) must be wondering if he was on some heavy druge, or just insane

He may be a snob, but that’s ok. I like critics with strong opinions, it would be boring, if there were no critics like him. When it comes to art, a little snobbishness is necessary, otherwise it would be pretty lame and wishy-washy. When you have taste (and I mean real taste, something elaborate, something to work on, not only consisting of “like it”, “not like it”) then there are things that you hate. And I like eloquent haters in criticism, they are entertaining and important.

This article sounds as if the person who wrote it felt offended by Wilson’s criticism. That’s ok, but it’s not ok to call someone like Wilson incompetent and bash upon him in this way. He has done so much for literature, he wrote some very fine pieces and he had taste. Not your taste, not mine, but his own. So you have to accept, that he had opinions that you don’t like on subjects which are important to you.

And, seriously, although I like Agatha Christie and this whole genre: it is not high literature when you compare it with people like Dostoevski, Shakespeare, Cechov or Proust. It is pretty good entertainment. But literature, for me, is more than that. It is deeper, richer, more complex, it tells me something about life, about psychology, about philosophy and the way we perceive things and if it is really really good literature it may change our perspective on many things. Last but not least, in literature language and style are very important things. For Christie language is just the means to tell a good story, for Proust or other writers, it is more, it represents the personality of the writer with all his idiosyncrasies, it is the medium of his art, it is itself art. All these things have no importance for Christie, she just wants to tell her story, she wants to present a mystery and the solution to it, for entertainment (and in this respect, she was extremely talented).

I know, it always sounds arrogant, when someone distinguishes between mere entertainment and art, but I think, that it is right and justified to distinguish between these two forms. Of course, in between these two, there is a grey area, there is a mix, especially in modern times. But I think it’s a failure to completely give up these borders.

RE Gorundium

Love your insightful words about the differences between mysteries and literature. I’m glad there are admirers of both, and won’t label those who prefer literature as snobs. Some people read for entertainment, others prefer to be moved and challenged with stories that convey truths about the human condition, with masterful use of language.