Every now and then, television demonstrates that it is capable of rising to the level of great art. Think of the excellent BBC miniseries Our Friends to the North and its sweeping storytelling ambition, which involved following a group of people from Newcastle over the course of thirty-one years. Or the amazing Albuquerque worldbuilding depicted in Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul. (The latter series, now about to air its final episodes, is so great that it is presently on track to outdoing the predecessor! No small feat, given that Breaking Bad was a masterpiece.) Or pretty much anything that David Simon has written.

But now — with its latest episode “Seven Seconds of Terror” (it dropped today) — I can state with absolute confidence that For All Mankind is the best fucking show on television. Hands down. And I say this as a huge fan of Better Call Saul. Nothing on television matches For All Mankind‘s acting, its narrative reach, and its ballsy and spellbinding storytelling. This is a show that has not only dared to present an alternative universe as a vast and bustling panorama. (In For All Mankind‘s timeline, the Soviets landed on the Moon first.) It has followed a series of utterly fascinating characters over the course of nearly three decades. People we come to care for and are mesmerized by. Earlier this season, the show presented us with a years-long montage of Margo and Sergei getting into an elevator while attending an annual conference. And the “Will they or won’t they?” question that undergirded this dynamic created exquisite and deeply felt sexual tension — one later played out in a hotel room in one of the hottest television scenes I’ve seen in years with the simple question “I would like you to kiss me.” (And this in a show that is primarily about a space race!) For All Mankind introduced a fascinating pre-Elon Musk entrepreneur named Dev Ayesa: a man who wants to use his private money to land the first person on Mars. Where other shows would have presented him as a sinister capitalist, For All Mankind was simply too nimble and fastidious to take such an easy way out. Instead, we see Dev as a man who is inclusive of his employees’ thoughts and opinions. There’s a part of him that actually cares about furthering humanity. But, of course, he’s also a businessman. We see geeks being unapologetically awkward and geeky. We see flawed heroes. Awesome women! Tons of women astronauts! And it’s multicultural! We get Aleida Rosales — a brilliant woman from Mexico who is the daughter of a janitor — and Danielle Poole — who has survived racism and tokenism to become a badass space jockey! But perhaps most important, we see what happens when perceived failures or marginalized types are given another chance. Indeed, the gentle (but by no means hokey) optimism of this show can be compared favorably to Star Trek at its best. And at a time in which the world seems to have become largely hopeless, For All Mankind reminds us of the greatness that humanity is capable of. And it does so without being saccharine about it.

The space travel in this show is not only tremendously exciting, but it’s rightly portrayed as deeply dangerous. And, as such, I have found myself hollering and shouting at the screen every week. I have felt a large and genuine thrill each week that I feel in every bone. During one particularly exciting and jaw-dropping moment a few weeks ago (I dare not spoil it), I gripped the arm of my chair so hard that the side knob on the undercarriage broke and I fell on my ass. But dammit if I didn’t smile and cheer my way through the episode with my newly accrued bruises, thinking absolutely nothing of them!

So, yeah, For All Mankind succeeds at being super-smart and terrifically emotional!

The writers are so consummate and attentive to detail that just about every single historical event has been factored into their plan. When the show jumps forward a decade, we get a zippy montage at the start of what has transpired in the intervening years, one that invites the kind of heavy scrutiny that has been applied to the Zapruder film. (To cite just a few of the historical switcheroos, Ted Kennedy and Gary Hart have been President. John Lennon was never assassinated in this universe. So we see the Beatles getting together for a reunion tour.) The show’s third season even had one of its characters run against Bill Clinton for President and win and it somehow managed to pull this amazing story move with confidence and believability!

Yet this television masterpiece is criminally overlooked by the critics who put together their year-end lists. They have completely ignored this tremendous creative achievement. While everyone has rightly raved over another Apple TV offering (Ted Lasso, which somehow managed to win over a skeptical realist like me), where are the For All Mankind stans? And why aren’t they more ubiquitous? We For All Mankind fans — those of us who have been watching from the very beginning — have to knock on secret doors and knock the rap on speakeasies just to find each other! But why? It is a goddamned crime that For All Mankind is not being talked about everywhere with the same rapturous glee that once accompanied every fresh episode of Mad Men.

The only bad move that this series has made is the clunky Danny/Karen subplot. But even with this fumble, For All Mankind‘s most recent episode indicates that it is about to rectify this mistake.

I believe in this show so enormously that I am not only telling you to watch it. I am ordering you to watch it. Art this great does not happen all that often. If we know each other, I will personally watch the whole damned run from the beginning with you. (Tonight, I made a pledge to do this with one dear friend.)

And to all you dopey television critics who think you’re so fucking intellectual, where the hell are you on this? Why have you stayed silent about For All Mankind? Yeah, I know who you are. I read you. And I’m going to make you a deal right now. If you talk up For All Mankind and you’re a member of the New York media who is on my shit list, I will completely forgive you and sing your praises. I’ll never write a hit piece on you. Because, goddamit, this show is too fucking important and too fucking great for you to sit this one out.

So watch For All Mankind. Start from the beginning and get together with friends. And tell them all that the wacky books guy from Brooklyn sent you.

And if you’re too lazy to read this longass rave, here’s my enthusiasm captured on video:

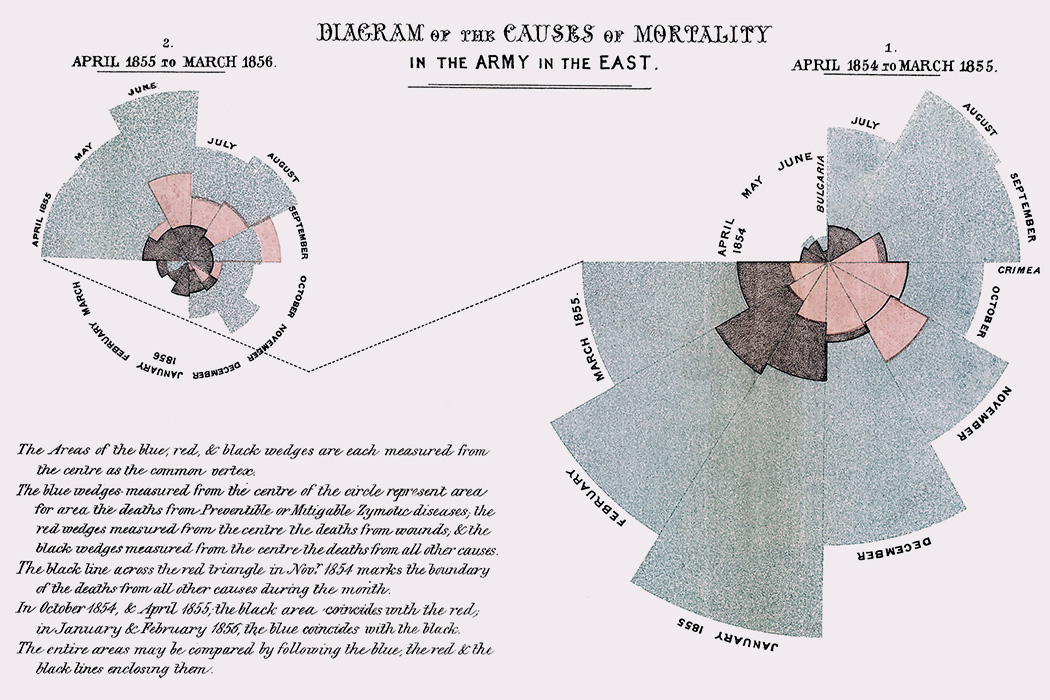

Of the four illustrious figures cannonaded in Eminent Victorians, Florence Nightingale somehow evaded the relentless reports of Lytton Strachey’s hard-hitting flintlocks. Strachey, of course, was constitutionally incapable of entirely refraining from his bloodthirsty barbs, yet even he could not find it within himself to stick his dirk into “the delicate maiden of high degree who threw aside the pleasures of a life of ease to succor the afflicted.” Despite this rare backpedaling from an acerbic male tyrant, Nightingale was belittled, demeaned, and vitiated for many decades by do-nothings who lacked her brash initiative and who were dispossessed of the ability to match her bold moves and her indefatigable logistical acumen, which were likely fueled by

Of the four illustrious figures cannonaded in Eminent Victorians, Florence Nightingale somehow evaded the relentless reports of Lytton Strachey’s hard-hitting flintlocks. Strachey, of course, was constitutionally incapable of entirely refraining from his bloodthirsty barbs, yet even he could not find it within himself to stick his dirk into “the delicate maiden of high degree who threw aside the pleasures of a life of ease to succor the afflicted.” Despite this rare backpedaling from an acerbic male tyrant, Nightingale was belittled, demeaned, and vitiated for many decades by do-nothings who lacked her brash initiative and who were dispossessed of the ability to match her bold moves and her indefatigable logistical acumen, which were likely fueled by