“For a while Scott talked of nothing but his lawsuit — in that half-joking, deadly serious way of his — then abruptly dropped the subject and focused on me. He wanted to know every detail of my life, or as many as I could provide in the half hour left to us: How did I meet my girlfriend? Did we sleep together on the first date? How much did I make as a teacher? Was it hard to get certified? What kind of car was I driving?” — Blake Bailey, The Splendid Things We Planned: A Family Portrait

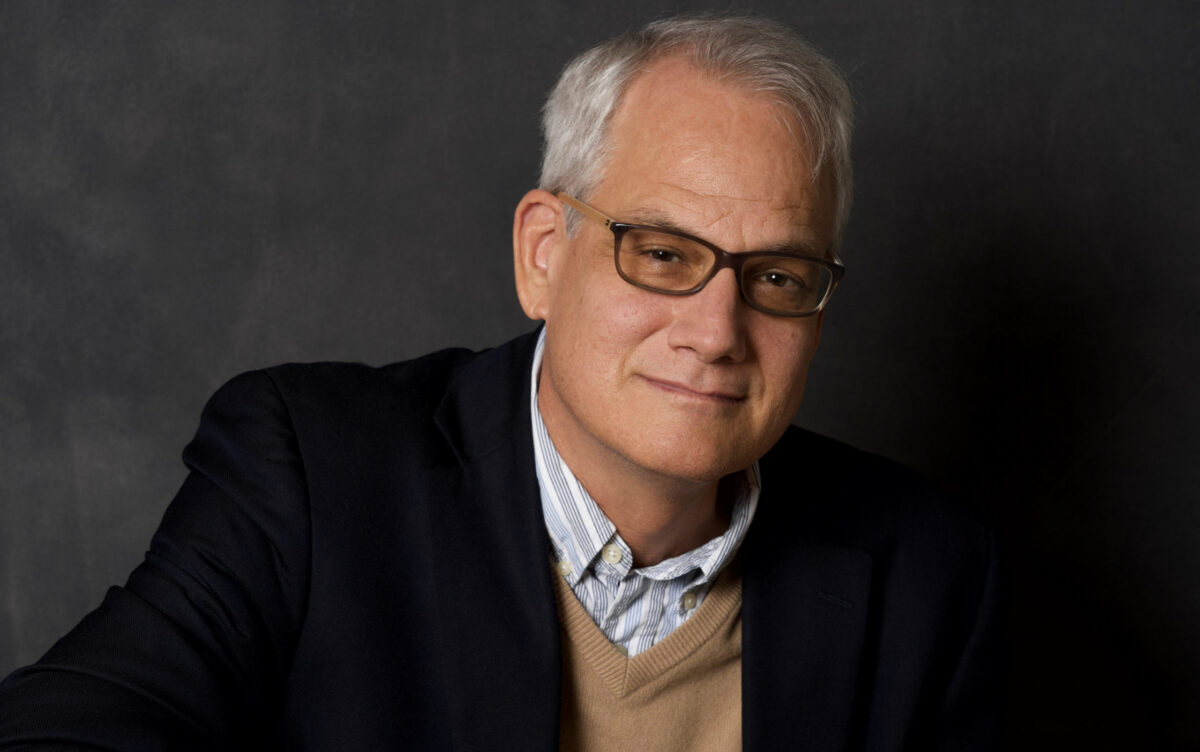

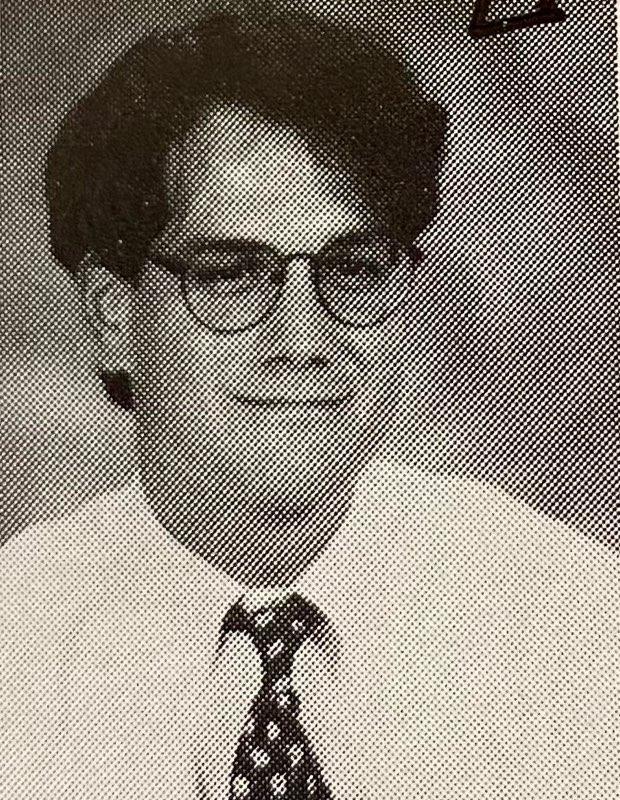

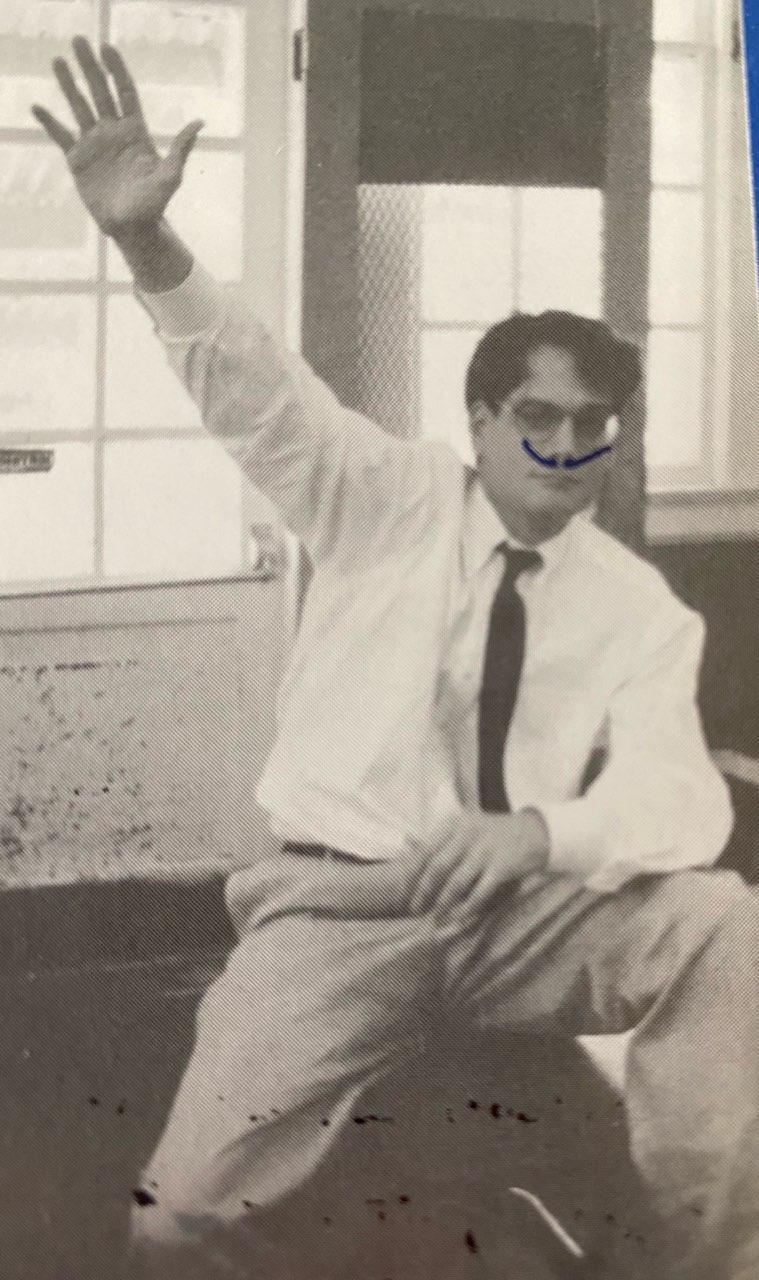

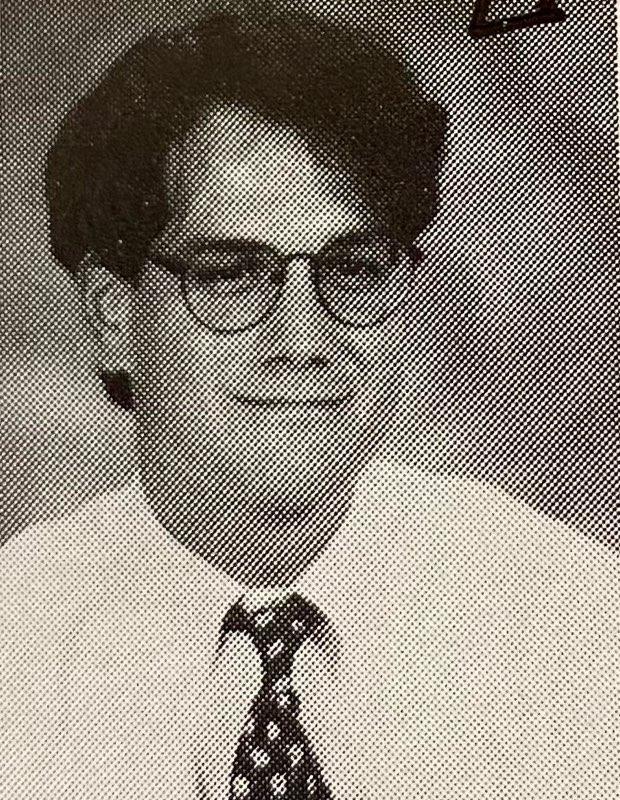

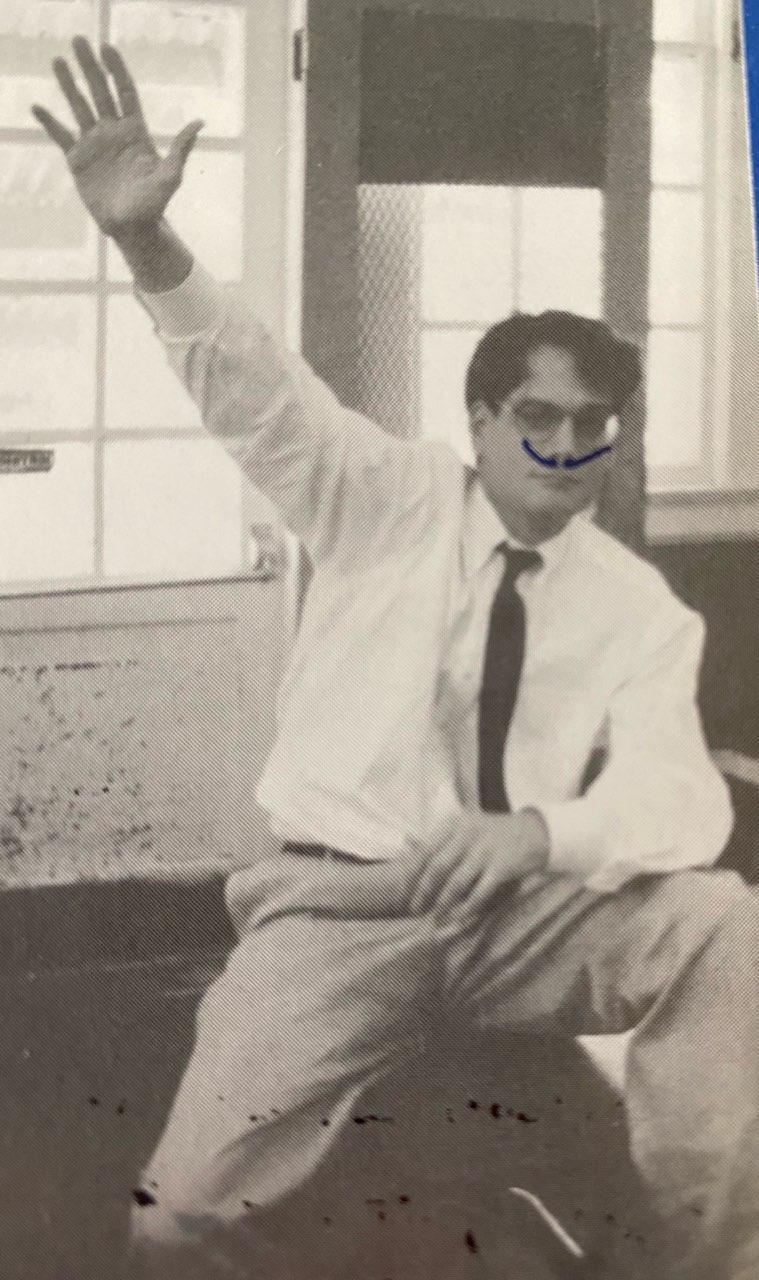

Like his brother, he was half-joking but deadly serious. He was the first teacher to speak to them as adults, to tell them that their feelings about life and literature were valid. Many of the girls, particularly the lonely girls who lived with single mothers and who longed for a father figure and who cloaked their anxieties beneath the breakneck bellow of flooding hormones and accruing acne, thought that he was brilliant and handsome, even if he did sometimes explode over a modest and pardonable transgression. If you whispered “Thank you” as your friend passed you some lip balm, his face would turn beet-red and the veins would bulge from his neck like logs under tarpaulin on a speeding truck. And this charismatic man, who always told you so sweetly that your thoughts were so special, would erupt with volcanic fury, his voice lurching from that weird theatrical amalgam of mid-Atlantic and a slight Southern tinge into something fierce and tyrannical. And then he’d assign you detention. “In retrospect,” said one of the dozens of former students who I spoke with on anonymity, “abusive people are like that.”

The girls were too young to understand this volatility. But they never questioned the teacher. They didn’t want to be summoned into the halls during the middle of class, where the teacher would move in close, close enough for an embrace, and lecture them about their outbursts or rebuke them for interrupting. Besides, they were smitten by him. The teacher wanted the girls to be smitten by them. Much as eighth-grade girls are often smitten by teachers. Given the pattern established by these allegations, it would appear that this was always the teacher’s plan. He told them that he had given up a writing career to teach them. He told them that teaching was his calling. His duty. He told him that this was the most important thing in his life and they were lucky to be part of it. The girls. And the boys, whom he was much harder on. But mostly the girls. Particularly the vulnerable ones.

The girls were too young to understand this volatility. But they never questioned the teacher. They didn’t want to be summoned into the halls during the middle of class, where the teacher would move in close, close enough for an embrace, and lecture them about their outbursts or rebuke them for interrupting. Besides, they were smitten by him. The teacher wanted the girls to be smitten by them. Much as eighth-grade girls are often smitten by teachers. Given the pattern established by these allegations, it would appear that this was always the teacher’s plan. He told them that he had given up a writing career to teach them. He told them that teaching was his calling. His duty. He told him that this was the most important thing in his life and they were lucky to be part of it. The girls. And the boys, whom he was much harder on. But mostly the girls. Particularly the vulnerable ones.

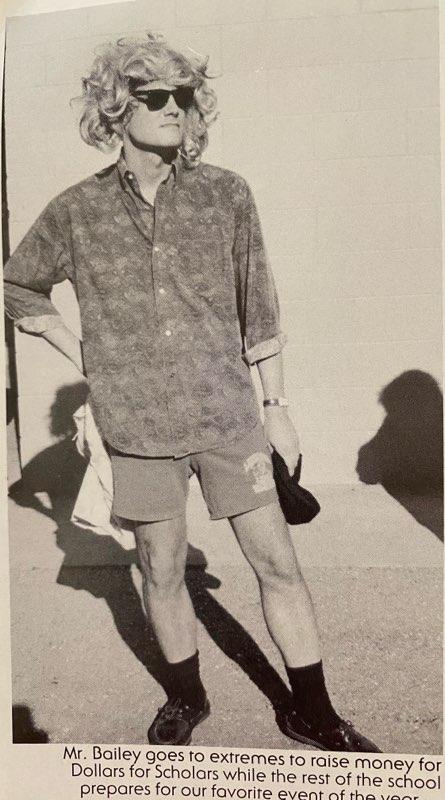

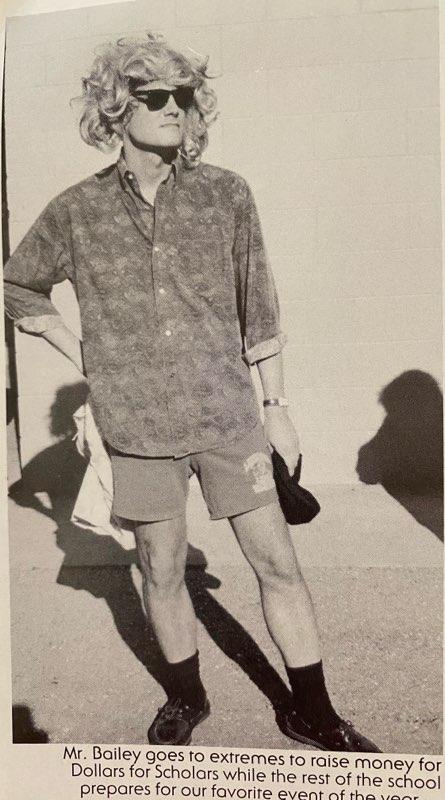

The girls alleged that he would move in close, sometimes too close, placing his hand upon their backs as he whispered bright words of burning promise into their ears. If he talked with you face-to-face, he would place his palm on your shoulder. It helped that he sometimes rolled in with a skateboard and quoted from Beavis and Butt-head and wore pleated khakis with the telltale imprint of a burned iron to suggest to these young girls that he was a fellow preadolescent who could be trusted. It helped that he assigned them Salinger and Yeats and Byron. Always men, never women. He forged their literary tastes, although some of his former students told me that they could never read Lolita again decades later. “He seems to view himself as this real-life modern-day Humbert Humbert,” said former student Sarah Stickney Murphy, who cited Bailey’s frequent assignments of The Catcher in the Rye. “Youth is innocence and truth. Older people are phonies.”

Bailey was strangely obsessed with The Carpenters’s “Close to You.” It is a song that several of Bailey’s former students permanently associate with Bailey. Multiple former students allege that he would lean in very close and sing the song very loud to their faces. Some students found this to be disturbing. One former student alleged that he took this further at a school dance, in which many of the girls were nervous and Bailey interfered with their budding lives by calling them up to the DJ booth and singing an a capella version of “Close to You” to various classmates. This struck the classmate as deeply inappropriate. It was almost as if Bailey viewed any boy at a junior high school dance as a rival.

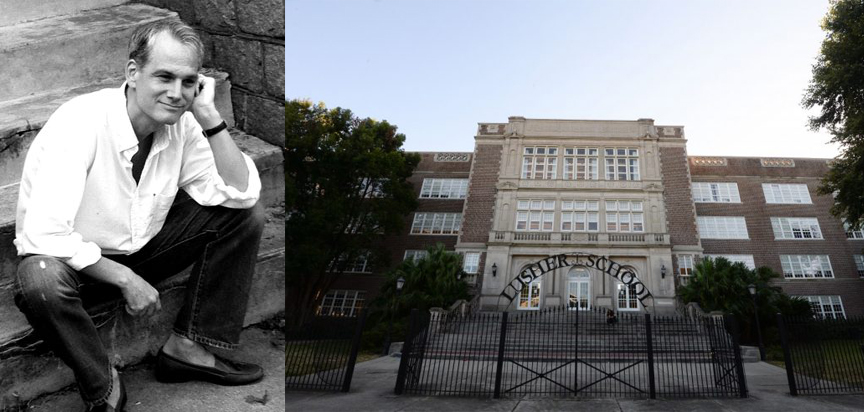

This was life at Lusher in the 1990s, if you were assigned the highly coveted English literature class taught by Blake Bailey, now a successful literary biographer with a bestseller on Philip Roth riding high on the New York Times bestseller list. Lusher was a top-ranked middle school that welcomed the wealthy and gifted kids of New Orleans, as well as other children from nearby neighborhoods. It was converted from a former courthouse. The school earned high marks for its emphasis on the arts. Typically, if you grew up in that area, you would start off at Edward Hynes (close to the City Park), make your way onto Lusher, and then finalize your primary education at Benjamin Franklin High School. Bailey taught at Lusher for a good ten years, winning the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities Teacher of the Year Award during his final year in 2000. Accounts vary as to what factors caused him to leave after this triumph. The school itself has been less than forthcoming in my efforts to obtain answers. Some insiders believe that he was strongly urged to resign and serve a final year. Some believe he ran away with a former student, although my thorough investigative efforts reveal that this isn’t true. But if you do the math and you add six years to twelve, you can probably draw a few conclusions over what may have transpired near the end of Bailey’s run. New Orleans is one of those “small town” big cities, where people talk and stories circulate and the pain and grief caused by a teacher who was wildly inappropriate with his students could only carry on for so long before it caught up with these girls in adulthood. The girls who went to Lusher have been talking with each other for decades and living with their pain, trying to make sense of what happened while sometimes contending with the great fear of speaking out, trying to understand how they could have been so easily manipulated. They were still starstruck with Bailey in college. And Bailey would stay in touch and meet them and betray their trust by being wantonly flirtatious. Some of the former students allege that they went up to the hotel room with him. Some allege that this was consensual. Some have carried their secrets for far too long and some have had rough lives afterward. Until now, their stories have been largely contained by the many beautiful lakes that surround the Big Easy.

This was life at Lusher in the 1990s, if you were assigned the highly coveted English literature class taught by Blake Bailey, now a successful literary biographer with a bestseller on Philip Roth riding high on the New York Times bestseller list. Lusher was a top-ranked middle school that welcomed the wealthy and gifted kids of New Orleans, as well as other children from nearby neighborhoods. It was converted from a former courthouse. The school earned high marks for its emphasis on the arts. Typically, if you grew up in that area, you would start off at Edward Hynes (close to the City Park), make your way onto Lusher, and then finalize your primary education at Benjamin Franklin High School. Bailey taught at Lusher for a good ten years, winning the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities Teacher of the Year Award during his final year in 2000. Accounts vary as to what factors caused him to leave after this triumph. The school itself has been less than forthcoming in my efforts to obtain answers. Some insiders believe that he was strongly urged to resign and serve a final year. Some believe he ran away with a former student, although my thorough investigative efforts reveal that this isn’t true. But if you do the math and you add six years to twelve, you can probably draw a few conclusions over what may have transpired near the end of Bailey’s run. New Orleans is one of those “small town” big cities, where people talk and stories circulate and the pain and grief caused by a teacher who was wildly inappropriate with his students could only carry on for so long before it caught up with these girls in adulthood. The girls who went to Lusher have been talking with each other for decades and living with their pain, trying to make sense of what happened while sometimes contending with the great fear of speaking out, trying to understand how they could have been so easily manipulated. They were still starstruck with Bailey in college. And Bailey would stay in touch and meet them and betray their trust by being wantonly flirtatious. Some of the former students allege that they went up to the hotel room with him. Some allege that this was consensual. Some have carried their secrets for far too long and some have had rough lives afterward. Until now, their stories have been largely contained by the many beautiful lakes that surround the Big Easy.

Bailey was dedicated to the mission, but he had designs of his own. For one student with the last name of Trujillo, he would cross her name out and correct it with “Tru-he-ho.” To this day, the student, who was one of the fortunate ones to evade Bailey’s attentions after Lusher, remains disturbed by a man abusing his authority to imply that she was a whore. Former students report that he would saunter into the “dance intensive” class which occupied the first two hours of the school day, the workshop run with a firm hand by Miss Burke. One former student claimed that Bailey would sit at the cafeteria table or stand at the door and watch these bright young things in their leotards contorting their bodies for about twenty minutes. He said nothing because he knew that Miss Burke never tolerated an interruption. But, as the student alleged, he had to get a peek at the girls. His girls. He was always watching them. He was always plotting. He was always waiting. Waiting for editors to accept his literary essays. His freelance journalism. His feeble stabs at fiction, which he was eventually forced to give up. What the hell else did he have to do? These were girls to be shaped and influenced. Girls who would grow up into young women. Not that he didn’t have sordid thoughts about them in the cafeteria, thoughts that, as these former students alleged, he would confess to them years later when they came of age.

And then, when the girls would change out of their leotards and join his class, he would dip further. He would have them write about their lives. He would urge the girls to “share their secrets.” The first writing assignment involved “chronicling the ups and downs of your life.” He would have his students make a list of the most formative traumatic experiences in their lives after reading Slaughterhouse Five. He insisted that this was purely a literary exercise. He told these girls — girls as young as twelve and no older than thirteen, girls that, in some cases, hadn’t even experienced their first kiss — that they were free to write about their blossoming sexuality. The only person who would read their journals would be him, just him. Mr. Bailey. Sometimes, if you showed enough initiative and willingness, he would take you to CC’s Coffee House and pay special attention to you. Particularly if you had problems. He would move in on the vulnerable ones. The ones who had drug and alcohol problems. The ones who had “issues.” The ones who had never been told that they were special.

“He definitely had a type,” recalls former Lusher student Megan Braden-Perry. “He liked white girls with dark hair and dark eyes. Stacked. Breasts and things. Those were his favorites.”

Even though many parents objected to Bailey’s attentive approach, the girls still longed for his attention. You could be be among the lucky few who Mr. Bailey corresponded with in high school and well into adult life. Mr. Bailey would mentor you. And then, when you were eighteen, he would meet you in a bar and eventually a hotel room to “discuss your career.” These eighth-graders had no idea that their teacher was waiting for them to hit the age of consent or maybe just a few years later after that just to be on the safe side. “As a non-drinker,” alleged one former student who described an encounter with Bailey when she was a freshman in college, “I ordered a Coke and I was over the moon to have so much face time with my mentor. When he placed his hand on my thigh and began asking me suggestive questions about my life, I shrugged it off as ‘He was drunk.’ I politely excused myself and promptly erased that encounter from my consciousness.”

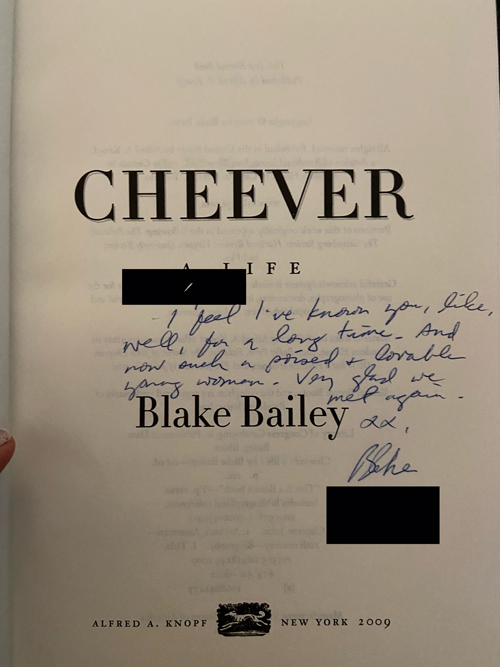

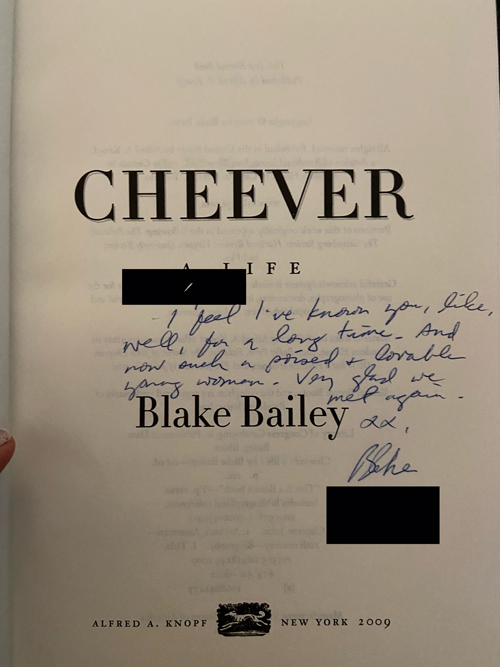

He would keep tabs on girls who had grown up, noting what cities they were in and contacting them whenever he rolled through town. During a 2009 promotional appearance for his John Cheever biography on the West Coast (the city has been elided to protect the alleged victim, but the incident has been corroborated by multiple individuals), he invited one of his former students to bring her sister along. He took the two young women to dinner after the reading. “I wasn’t initially hesitant,” alleged this sister, “but as the evening wore on, I could tell Bailey was fixated on us. He watched us the entire time he was doing the reading.” When the former student left the table to go to the restroom, Bailey allegedly revealed to this sister all of the inappropriate thoughts he had about her when she was thirteen, in the days when she would pick up her sister or her friend from school. “Do you know how hard it was to resist you back then?” said Bailey, as alleged by the sister. “The things we wrote and how you looked?” Then, Bailey invited the two sisters to return to his hotel room because “it had an amazing library.” The two sisters knew that they had to stick together. They didn’t want Bailey to make any moves.

He would keep tabs on girls who had grown up, noting what cities they were in and contacting them whenever he rolled through town. During a 2009 promotional appearance for his John Cheever biography on the West Coast (the city has been elided to protect the alleged victim, but the incident has been corroborated by multiple individuals), he invited one of his former students to bring her sister along. He took the two young women to dinner after the reading. “I wasn’t initially hesitant,” alleged this sister, “but as the evening wore on, I could tell Bailey was fixated on us. He watched us the entire time he was doing the reading.” When the former student left the table to go to the restroom, Bailey allegedly revealed to this sister all of the inappropriate thoughts he had about her when she was thirteen, in the days when she would pick up her sister or her friend from school. “Do you know how hard it was to resist you back then?” said Bailey, as alleged by the sister. “The things we wrote and how you looked?” Then, Bailey invited the two sisters to return to his hotel room because “it had an amazing library.” The two sisters knew that they had to stick together. They didn’t want Bailey to make any moves.

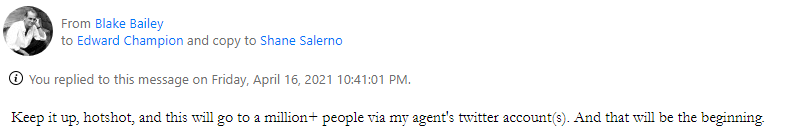

Bailey would wait years for his former students to grow up. Then, as several of his students have alleged, he would invite them for drinks and ply them with liquor and get handsy, often blaming these wild flirtations on drunken behavior. But in the case of his former students, because all of his alleged victims were over the age of eighteen, if they wanted to go up to his hotel room, it was all perfectly legal. That’s what Bailey would tell anyone who was creeped out by his behavior. It is indeed what Bailey has emailed a number of people, including me, in the last few days. As Bailey emailed me on Friday night, “It is untrue that I EVER committed an illegal sexual act, regardless of what comes out of the woodwork to say so.”

Bailey would wait years for his former students to grow up. Then, as several of his students have alleged, he would invite them for drinks and ply them with liquor and get handsy, often blaming these wild flirtations on drunken behavior. But in the case of his former students, because all of his alleged victims were over the age of eighteen, if they wanted to go up to his hotel room, it was all perfectly legal. That’s what Bailey would tell anyone who was creeped out by his behavior. It is indeed what Bailey has emailed a number of people, including me, in the last few days. As Bailey emailed me on Friday night, “It is untrue that I EVER committed an illegal sexual act, regardless of what comes out of the woodwork to say so.”

Some of Bailey’s alleged victims have claimed that they went up to Bailey’s hotel room after one too many drinks with Bailey and things happened. They alleged that they were coerced to do so. But I have honored their request not to go public. As I was putting together this story, a New Orleans reporter by the name of Ramon Antonio Vargas contacted many of the same parties. The two of us were in touch during our respective investigations and exchanged some information to ensure that we were both accurate in reporting these allegations. According to Vargas, one of the students he talked to accused Bailey of rape. Among some of the more stunning revelations:

He kept in touch with both after they left Lusher and progressed through high school. They both said he often checked in on their love lives and showed an unusual interest in their virginity, frequently asking: “Have you punched your V-card yet?”

Bailey also allegedly told one of his alleged victims, when she rolled off of bed, “What is wrong with you? You just don’t know how the game is played.”

But the pattern that Vargas and I have established from the allegations of these brave women is clear: Find a vulnerable young girl, befriend her, stay in touch with her over the years, wait until she turns eighteen, and then invite her for drinks and try to bed her.

* * *

Bailey has suffered few consequences for this despicable behavior, but he is not entirely immune. On April 18th, when courageous women started coming forward after I wrote an essay which documented the rampant misogyny in Bailey’s writing, his agents at The Story Factory swiftly dropped him (and they were courteous enough to promptly inform me). On the other hand, his publisher, W.W. Norton, has refused to return my phone calls and emails. On April 18th, Bailey threatened me by email to launch a smear campaign against me (although he did later issue an apology). A magazine that I pitched this investigation to also went silent, opting instead to promote an excerpt from Bailey’s Roth biography on its Twitter feed. Few literary people have said anything about these allegations. Indeed, many blue checkmarks — most notably, putative #metoo champion and current literary superstar Taffy Brodesser-Akner (who did not return my email) — were merrily yukking it up with Bailey on Twitter in the days after these allegations were first brought to public light. Bailey is now so deeply entrenched in the literary world that he is near bulletproof. And yet several sources who have had contact with Bailey in recent years have reported to me that he has aggressively charmed the daughters of friends and acquaintances and that he is still using the same moves on twelve-year-olds that he cultivated at Lusher. Some who are friendly with Bailey are not surprised by the allegations. But they have opted not to go on the public record. And I respect their decision.

I contacted Bailey by email with a number of questions in relation to these allegations. My last question to him was this: “What steps do you plan to take to correct your wildly inappropriate behavior and alleged abuse of these women (which I understand to be ongoing)?” That Blake Bailey could not even answer this basic question suggests that contrition, restitution, and owning up to his alleged awful treatment of the women he harmed may very well be beyond his capabilities. Instead, Bailey threatened me with legal action through his attorney, Billy Gibbens, and claimed that he would pursue “all available legal remedies” if I published “any further anonymous, uncorroborated, false allegations about Mr. Bailey.” Gibbens also used The Los Angeles Times as a bully pulpit, calling me “a notorious internet troll” and claiming the allegations to be “scurrilous charges.” Unfortunately, for Bailey and Mr. Gibbons, the comments in question are protected by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. In constructing this story, I have relied on testimony from multiple alleged victims and witnesses and have taken great care to ensure that it is fair and accurate. To further clarify my intentions and my First Amendment rights, I do not intend malice with my investigation of these allegations.

Having managed to flee New Orleans and establish some modest literary fame on the national stage, there is little doubt that Blake Bailey truly believes he can get away with anything. And this is because the literary and media worlds in which he has operated and roosted for so many years have become so accustomed to looking the other way. Particularly in relation to the abuse and victimization of women.

4/20/2021 9:30 PM UPDATE: A previous version of this story featured inaccurate geographic details about the Lusher School. This article has been corrected. I regret the error.

4/21/2021 11:50 AM UPDATE: Ramon Antonio Vargas reports that Norton has paused shipping and promotional events on Bailey’s Roth biography. I tried contacting all of my publicity contacts at Norton by phone. Every voicemail I reached was full. Clearly, this story has grown legs.

4/21/2021 2:50 PM UPDATE: Blake Bailey has deleted his Twitter account.

4/22/2021 6:30 AM UPDATE: In a devastating article published on Wednesday night by The New York Times‘s Alexandra Alter and Rachel Abrams, the two reporters uncovered an alleged rape that occurred in 2015:

That same year, Valentina Rice, a publishing executive, met Mr. Bailey at the home of Dwight Garner, a book critic for The Times, and his wife in Frenchtown, N.J. A frequent guest at their home, Ms. Rice, 47, planned to stay overnight, as did Mr. Bailey, she said. After she went to bed, Mr. Bailey entered her room and raped her, she said. She said “no” and “stop” repeatedly, she said in an interview.

According to the Times, Rice attempted to remedy the assault by approaching Norton president Julia A. Reidhead, offering to confirm this allegation. Reidhead never responded, but, one week after Rice sent the note, Bailey did. What’s so jaw-dropping here is that it appears that email was simply forwarded onto Bailey and that Reidhead had never planned to investigate. My emails to various Norton people on this subject have not been returned. The Times piece also notes that Bailey was paid a mid-six-figure advance for the Roth biography.

4/22/2021 7:00 PM UPDATE: The New Orleans Advocate‘s Ramon Antonio Vargas has posted a new followup article on Blake’s former students at Lusher. One of the alleged victims was only seventeen, just past the age of consent in Louisiana.

4/29/2021 UPDATE: Eve Peyton has written a devastating first-person account of her experience at Slate.

The girls were too young to understand this volatility. But they never questioned the teacher. They didn’t want to be summoned into the halls during the middle of class, where the teacher would move in close, close enough for an embrace, and lecture them about their outbursts or rebuke them for interrupting. Besides, they were smitten by him. The teacher wanted the girls to be smitten by them. Much as eighth-grade girls are often smitten by teachers. Given the pattern established by these allegations, it would appear that this was always the teacher’s plan. He told them that he had given up a writing career to teach them. He told them that teaching was his calling. His duty. He told him that this was the most important thing in his life and they were lucky to be part of it. The girls. And the boys, whom he was much harder on. But mostly the girls. Particularly the vulnerable ones.

The girls were too young to understand this volatility. But they never questioned the teacher. They didn’t want to be summoned into the halls during the middle of class, where the teacher would move in close, close enough for an embrace, and lecture them about their outbursts or rebuke them for interrupting. Besides, they were smitten by him. The teacher wanted the girls to be smitten by them. Much as eighth-grade girls are often smitten by teachers. Given the pattern established by these allegations, it would appear that this was always the teacher’s plan. He told them that he had given up a writing career to teach them. He told them that teaching was his calling. His duty. He told him that this was the most important thing in his life and they were lucky to be part of it. The girls. And the boys, whom he was much harder on. But mostly the girls. Particularly the vulnerable ones. This was life at Lusher in the 1990s, if you were assigned the highly coveted English literature class taught by Blake Bailey, now a successful literary biographer with a bestseller on Philip Roth riding high on the New York Times bestseller list. Lusher was a top-ranked middle school that welcomed the wealthy and gifted kids of New Orleans, as well as other children from nearby neighborhoods. It was converted from a former courthouse. The school earned high marks for its emphasis on the arts. Typically, if you grew up in that area, you would start off at Edward Hynes (close to the City Park), make your way onto Lusher, and then finalize your primary education at Benjamin Franklin High School. Bailey taught at Lusher for a good ten years, winning the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities Teacher of the Year Award during his final year in 2000. Accounts vary as to what factors caused him to leave after this triumph. The school itself has been less than forthcoming in my efforts to obtain answers. Some insiders believe that he was strongly urged to resign and serve a final year. Some believe he ran away with a former student, although my thorough investigative efforts reveal that this isn’t true. But if you do the math and you add six years to twelve, you can probably draw a few conclusions over what may have transpired near the end of Bailey’s run. New Orleans is one of those “small town” big cities, where people talk and stories circulate and the pain and grief caused by a teacher who was wildly inappropriate with his students could only carry on for so long before it caught up with these girls in adulthood. The girls who went to Lusher have been talking with each other for decades and living with their pain, trying to make sense of what happened while sometimes contending with the great fear of speaking out, trying to understand how they could have been so easily manipulated. They were still starstruck with Bailey in college. And Bailey would stay in touch and meet them and betray their trust by being wantonly flirtatious. Some of the former students allege that they went up to the hotel room with him. Some allege that this was consensual. Some have carried their secrets for far too long and some have had rough lives afterward. Until now, their stories have been largely contained by the many beautiful lakes that surround the Big Easy.

This was life at Lusher in the 1990s, if you were assigned the highly coveted English literature class taught by Blake Bailey, now a successful literary biographer with a bestseller on Philip Roth riding high on the New York Times bestseller list. Lusher was a top-ranked middle school that welcomed the wealthy and gifted kids of New Orleans, as well as other children from nearby neighborhoods. It was converted from a former courthouse. The school earned high marks for its emphasis on the arts. Typically, if you grew up in that area, you would start off at Edward Hynes (close to the City Park), make your way onto Lusher, and then finalize your primary education at Benjamin Franklin High School. Bailey taught at Lusher for a good ten years, winning the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities Teacher of the Year Award during his final year in 2000. Accounts vary as to what factors caused him to leave after this triumph. The school itself has been less than forthcoming in my efforts to obtain answers. Some insiders believe that he was strongly urged to resign and serve a final year. Some believe he ran away with a former student, although my thorough investigative efforts reveal that this isn’t true. But if you do the math and you add six years to twelve, you can probably draw a few conclusions over what may have transpired near the end of Bailey’s run. New Orleans is one of those “small town” big cities, where people talk and stories circulate and the pain and grief caused by a teacher who was wildly inappropriate with his students could only carry on for so long before it caught up with these girls in adulthood. The girls who went to Lusher have been talking with each other for decades and living with their pain, trying to make sense of what happened while sometimes contending with the great fear of speaking out, trying to understand how they could have been so easily manipulated. They were still starstruck with Bailey in college. And Bailey would stay in touch and meet them and betray their trust by being wantonly flirtatious. Some of the former students allege that they went up to the hotel room with him. Some allege that this was consensual. Some have carried their secrets for far too long and some have had rough lives afterward. Until now, their stories have been largely contained by the many beautiful lakes that surround the Big Easy.  He would keep tabs on girls who had grown up, noting what cities they were in and contacting them whenever he rolled through town. During a 2009 promotional appearance for his John Cheever biography on the West Coast (the city has been elided to protect the alleged victim, but the incident has been corroborated by multiple individuals), he invited one of his former students to bring her sister along. He took the two young women to dinner after the reading. “I wasn’t initially hesitant,” alleged this sister, “but as the evening wore on, I could tell Bailey was fixated on us. He watched us the entire time he was doing the reading.” When the former student left the table to go to the restroom, Bailey allegedly revealed to this sister all of the inappropriate thoughts he had about her when she was thirteen, in the days when she would pick up her sister or her friend from school. “Do you know how hard it was to resist you back then?” said Bailey, as alleged by the sister. “The things we wrote and how you looked?” Then, Bailey invited the two sisters to return to his hotel room because “it had an amazing library.” The two sisters knew that they had to stick together. They didn’t want Bailey to make any moves.

He would keep tabs on girls who had grown up, noting what cities they were in and contacting them whenever he rolled through town. During a 2009 promotional appearance for his John Cheever biography on the West Coast (the city has been elided to protect the alleged victim, but the incident has been corroborated by multiple individuals), he invited one of his former students to bring her sister along. He took the two young women to dinner after the reading. “I wasn’t initially hesitant,” alleged this sister, “but as the evening wore on, I could tell Bailey was fixated on us. He watched us the entire time he was doing the reading.” When the former student left the table to go to the restroom, Bailey allegedly revealed to this sister all of the inappropriate thoughts he had about her when she was thirteen, in the days when she would pick up her sister or her friend from school. “Do you know how hard it was to resist you back then?” said Bailey, as alleged by the sister. “The things we wrote and how you looked?” Then, Bailey invited the two sisters to return to his hotel room because “it had an amazing library.” The two sisters knew that they had to stick together. They didn’t want Bailey to make any moves. Bailey would wait years for his former students to grow up. Then, as several of his students have alleged, he would invite them for drinks and ply them with liquor and get handsy, often blaming these wild flirtations on drunken behavior. But in the case of his former students, because all of his alleged victims were over the age of eighteen, if they wanted to go up to his hotel room, it was all perfectly legal. That’s what Bailey would tell anyone who was creeped out by his behavior. It is indeed what Bailey has emailed a number of people, including me, in the last few days. As Bailey emailed me on Friday night, “It is untrue that I EVER committed an illegal sexual act, regardless of what comes out of the woodwork to say so.”

Bailey would wait years for his former students to grow up. Then, as several of his students have alleged, he would invite them for drinks and ply them with liquor and get handsy, often blaming these wild flirtations on drunken behavior. But in the case of his former students, because all of his alleged victims were over the age of eighteen, if they wanted to go up to his hotel room, it was all perfectly legal. That’s what Bailey would tell anyone who was creeped out by his behavior. It is indeed what Bailey has emailed a number of people, including me, in the last few days. As Bailey emailed me on Friday night, “It is untrue that I EVER committed an illegal sexual act, regardless of what comes out of the woodwork to say so.”