On Tuesday afternoon, the Associated Press’s Hillel Italie reported that a recently published spy novel — Q.R. Markham’s Assassin of Secrets — was being pulled after Markham’s publisher, Mulholland Books, had determined that Markham had lifted his text from other sources.

Reluctant Habits has obtained a finished copy of the Markham book. The following examples, compared from Markham’s book to the original sources, demonstrate just how much Markham (real name: Quentin Rowan) stole from other material.

Markham, Page 13: “His step had an unusual silence to it. It was late morning in October of the year 1968 and the warm, still air had turned heavy with moisture, causing others in the long hallway to walk with a slow shuffle, a sort of somber march.”

Taken from Page 1 of James Bamford’s Body of Secrets: Anatomy of the Ultra-Secret National Security Agency: “His step had an unusual urgency to it. Not fast, but anxious, like a child heading out to recess who had been warned not to run. It was late morning and the warm, still air had turned heavy with moisture, causing others on the long hallway to walk with a slow shuffle, a sort of somber march.”

Markham, Page 13: “The boxy, sprawling Munitions Building which sat near the Washington Monument and quietly served as I-Division’s base of operations was a study in monotony. Endless corridors connecting to endless corridors. Walls a shade of green common to bad cheese and fruit. Forests of oak desks separated down the middle by rows of tall columns, like concrete redwoods, each with a number designating a particular work space.”

Taken from Bamford, Page 1: “In June 1930, the boxy, sprawling Munitions Building, near the Washington Monument, was a study in monotony. Endless corridors connecting to endless corridors. Walls a shade of green common to bad cheese and fruit. Forests of oak desks separated down the middle by rows of tall columns, like concrete redwoods, each with a number designating a particular work space.”

Markham, Page 13: “Chase’s brown loafers made a sudden soundless left turn into a heavily deserted wing. It was lined with closed doors containing dim, opaque windows and empty name holders.”

Taken from Bamford, Page 1: “Oddly, he made a sudden left turn into a nearly deserted wing. It was lined with closed doors containing dim, opaque windows and empty name holders.”

Markham, Page 14: “…Chase mused, as he turned right into Room 32, a small office containing a massive black vault, the kind found in exclusive Swiss banks. Reaching into the front pocket of his gingham shirt, he removed a small card. Then, standing in front of the thick round combination dial, he began twisting it back and forth. Seconds later he yanked up the silver bolt and slowly pushed open the heavy door, only to reveal another wall of steel behind it. This time he removed a key from a small compartment inside the heel of his left shoe and turned it in the lock, swinging aside the second door to reveal an interior as bright and cheery as noonday sun.”

Taken from Bamford, Page 1-2: “Halfway down the hall Friedman turned right into Room 3416, a small office containing a massive black vault, the kind found in large banks. Reaching into his inside coat pocket, he removed a small card. Then, standing in front of the thick round combination dial to block the view, he began twisting the dial back and forth. Seconds later he yanked up the silver bolt and slowly pulled open the heavy door, only to reveal another wall of steel behind it. This time he removed a key from his trouser pocket and turned it in the lock, swinging aside the second door to reveal an interior as dark as a midnight lunar eclipse.”

Markham, Page 14: “Yet somehow, at forty-eight years old, Virginia-born Brewster had spent his entire adult life studying, practicing, defining the black arts of espionage and counterintelligence. Six years earlier, during the autumn of 1962, Brewster had been appointed the chief and sole employee of a secret new organization responsible for monitoring — ‘watchdogging,’ in the new president’s words — all of the other intelligence services: the CIA in particular.”

Taken from Bamford, Page 1: “At thirty-eight years old, the Russian-born William Frederick Friedman had spent most of his adult life studying, practicing, defining the black art of code-breaking. The year before, he had been appointed the chief and sole employee of a secret new Army organization responsible for analyzing and cracking foreign codes and ciphers. Now, at last, his one-man Signal Intelligence Service actually had employees, three of them, who were attempting to keep pace close behind.”

Markham, Page 15: “He was a natural administrator; he absorbed written material at a glance and never forgot anything. He knew the names and pseudonyms, the photographs, and the operative weakness of every agent controlled by Americans everywhere in the world. Brewster rarely met with any of them, and few of them knew he existed, but he designed their lives, forming them into a global subsociety that had become what it was, and remained so, at his pleasure. He was outranked by only three men in the American intelligence community.”

Taken from Charles McCarry’s The Tears of Autumn: “He was a natural administrator; he absorbed written material at a glance and never forgot anything. He knew the names and pseudonyms, the photographs and the operative weakness of every agent controlled by Americans everywhere in the world. Patchen never met any of them, and none of them knew he existed, but he designed their lives, forming them into a global sub-society that had become what it was, and remained so, at his pleasure. His hair turned gray when he was thirty, possibly from the pain of his wounds. At thirty-five he was outranked by only four men in the American intelligence community.”

Markham, Page 15: “The machine measured their breathing, the sweat on their palms, their blood pressure and pulse, and it knew whether they had stolen money from the government, submitted to homosexual advances, been doubled by the opposition, committed adultery. The test was called the ‘flutter.'”

Markham, Page 15: “The machine measured their breathing, the sweat on their palms, their blood pressure and pulse, and it knew whether they had stolen money from the government, submitted to homosexual advances, been doubled by the opposition, committed adultery. The test was called the ‘flutter.'”

Taken from Charles McCarry’s The Tears of Autumn: “The machine measured their breathing, the sweat on their palms, their blood pressure and pulse, and it knew whether they had stolen money from the government, submitted to homosexual advances, been doubled by the opposition, committed adultery. The test was called the ‘flutter.'”

Markham, Pages 15-16: “To Brewster, the heart attack machine was the ordeal of brotherhood. He believed that those who went through it were cold in their minds, trained to observe and report but never to judge. They looked for flaws in humanity and were never surprised to find them; the polygraph had taught Chase so much about himself — taught him that guilt can be read on human skin with a meter.”

From Charles McCarry’s The Tears of Autumn: “To Webster, the flutter was the ordeal of brotherhood. He believed that those who went through it were cold in their minds, trained to observe and report but never to judge. They looked for flaws in men and were never surprised to find them: the polygraph had taught them so much about themselves — taught them that guilt can be read on human skin with a meter — that they knew what all men were.”

Markham, Pages 16-17: “His number two agent wore large horn-rimmed eyeglasses, had dirty-blond hair that covered his forehead and the tops of his ears, was broad-shouldered but slim, and very handsome. His eyes were a warm blue and he had the kind of weather-beaten face that suggested years of outdoor activity. Chase almost had the look of an old-time matinee idol, but there was a certain quirkiness, a wistfulness, a rueful irony to his face that left a different kind of emotional trademark. An almost dandified alienation. This, Brewster guessed, was what had endeared his number two man to all those serious dark-haired women in Paris and Milan.”

Taken from two sources (1) Raymond Benson’s High Time to Kill: “Group Captain Roland Marquis was blond, broad-shouldered, and very handsome. A neatly trimmed blond mustache covered his upper lip. His eyes were a cold blue. He had the kind of weather-beaten face that suggested years of outdoor activity, and the square jaw of a matinee idol.” (2) Geoffrey O’Brien’s Dream Time: “The mark this leaves on him is not shame but rather the wistfulness of the spy, his self-indulgent rueful irony, an emotional trademark that endears him to serious dark-haired women in Brussels and Milan. They are attracted to the way he embodies a dandified alienation.”

Markham, Page 17: “Also, it was evident to Brewster from the day he met Chase in Korea that he was the finest natural spy he had ever encountered. There was no easy explanation for his talent. Perhaps the first reason for his excellence was his truculent refusal to believe in anybody’s innocence. Chase treated all men and women as enemy agents at all times; they could be used, paid, praised. They could be loved. But they could never be trusted. What might seem paranoia in another man was shrewd intuition in Chase.”

Taken from Charles McCarry, The Last Supper: “Also, it was evident to Hubbard from the day Wolkowicz arrived in Berlin that he was the finest natural spy he had ever encountered. There was no easy explanation for this talent. Perhaps the first reason for his excellence was his truculent refusal to believe in anybody’s innocence. Wolkowicz treated all men, and especially all women, as enemy agents at all times; they could be used, paid, praised. What might seem paranoia in another man was shrewd intuition in Wolkowicz.”

Markham, P. 18:: “They’re reportedly responsible for the theft of those military maps from Hanoi from the Pentagon last month. A well-protected Mafia don was murdered about a year ago in Cuba. Zero Directorate supposedly supplied the hit man for that job.”

Taken from Raymond Benson’s High Time to Kill: “The maps disappeared from right under the noses of highly trained security personnel. A well-protected Mafia don was murdered about a year ago in Sicily. The Union supposedly supplied the hit man for that job.”

Markham, P. 20: “Some even thought he operated outside the apparatus; in fact, he was implanted so deeply within it as to be more or less detached from its rules.”

From Charles McCarry, Second Sight: “…he operated outside the apparatus; in fact he was implanted so deeply within it as to be detached from its rules.”

Markham, P. 20: “But what happens to the market if you can’t keep a secret, if you never know which one of your people is going to be grabbed next and given a shot of something that makes him want to tell everything he knows?”

From Charles McCarry, Second Sight: “But what happens to the market if you can’t keep a secret, if you never know which one of your people is going to be grabbed next and given a shot of something that makes him want to tell everything he knows?”

Markham, P. 21-22: “It made him think of a warm autumn evening a year before the shooting of John F. Kennedy when the president preempted regular television programming to give advance notice of the possible erasure of the world. Chase had been walking down K Street when the neon was just coming on. People were walking around in the usual way. Never had ordinary gestures — buying a newspaper, putting the key in the lock, shoving a quarter across the counter at the luncheonette — seemed so submissive, so humiliated. Even if a more precise hour were fixed for the great dissolution, the hand would continue in automaton fashion to shove the coin across the counter.”

From Geoffrey O’Brien’s Dream Time: “A year before the shooting of John F. Kennedy, for instance, on a warm autumn evening the President preempted regular television programming to give advance notice of the possible erasure of the world. On the street the neon was just coming on. People were walking around in the usual way. Never had ordinary gestures — buying a newspaper, putting the key in the lock, shoving a quarter across the counter, waiting on line to see the new adventure movie — seemed so submissive, so humiliated. The people on the street had in any case no way of responding. Even if a more precise hour were fixed for the great dissolution, the hand would continue in automaton fashion to shove the coin across the counter.”

Markham, P. 22: “As Chase himself would say years later, when he knew him better than anyone alive, the old man decided everything between his pelvis and his collarbone. Chase meant this as a compliment: anyone could be an intellectual.”

From Charles McCarry, Second Sight: “As Patchen himself would say years later, when he knew him better than anyone alive, the old man decided everything between his pelvis and his collarbone. He meant this as a compliment: any damn fool could be an intellectual.”

Markham, P. 23: “…they called it that, never the ‘Soviet intelligence service’ or ‘the KGB,’ because in Brewster’s opinion there as no such thing as the Soviet Union, only the Russian empire operating under an assumed name.”

From Charles McCarry, Second Sight: “…never ‘the Soviet intelligence service’ or ‘the KGB,’ because in their opinion there was no such thing as the Soviet Union, only the Russian empire operating under an assumed name.”

Markham, P. 23: “The victims were doing the Russians no harm, and even if the opposite had been true, it is seldom good practice for an intelligence service to kill an enemy it knows, because the victim will only be replaced by one that it does not know…”

From Charles McCarry, Second Sight: “The victims were doing the Russians no harm, and even if the opposite had been true, it is seldom good practice for an intelligence service to kill an enemy it knows, because the victim will only be replaced by one that it does not know.”

Markham, P. 24: “He spoke fluent Arabic and English and was an expert in small arms, explosives, and small-scale guerrilla operations. ‘The strange thing about the operation,’ Brewster had noted at the time, ‘is that all of Lazarus’s shooters and all the supporting cast are bourgeois European leftists and students.”

From Charles McCarry, Second Sight: “He spoke fluent Arabic and English and was an expert in small arms, explosives, and small-scale guerrilla operations. ‘The strange thing about this operation,’ Horace reported, ‘is that all of Butterfly’s shooters and all the supporting cast are Palestinian Arabs or bourgeois European leftists — romantic females, in about half the cases — who sympathize with the Palestinian cause.'”

Markham, P. 25:: “Black images of hundreds of small rectangles were scattered all over the torso and legs. ‘Who took this?’ ‘We did, in Milan, while he was waiting for his bags. Those are two-ounce gold ingots, two hundred and twenty…”

From Charles McCarry, Second Sight: “Black images of hundreds of small rectangles were scattered all over the torso and legs. ‘Who took this?’ Yeho asked. ‘We did, in Milan, while he was waiting for his bags. Those are two-ounce gold ingots, two hundred and twenty of them…'”

Markham, P. 25: “Lazarus’s mission had been to create an asylum full of lunatics, and then unlock the doors and let them go. He was going to give them twenty-eight pounds of gold and a million dollars in currency, tell them they could kill anyone they wanted to kill anyone…”

From Charles McCarry, Second Sight: “Butterfly’s mission had been to create an asylum full of lunatics, and then unlock the doors and let them go. He was going to give them twenty-eight pounds of gold and a million dollars in currency, tell them they could kill anyone they…”

Markham, P. 26: “Brewster gazed at Chase for several seconds in great seriousness — taking a quiet amount of pride in his creation. Then he threw back his head and laughed. ‘I was right, by golly,’ Brewster said.”

From Charles McCarry, Second Sight: “The OG gazed at him for several seconds in great seriousness. Then he threw back his head and laughed. ‘I was right, by golly,’ he said.”

Markham, P. 26: “An odd nickname for the elegant, tall, and very efficient and liberated young lady with a taste for cocktail dresses and thigh-high boots. After a slightly shaky start, Chase and Frankie had become close friends and what she liked to call ‘occasional lovers.'”

From John Gardner, Special Services: “An apt nickname for the elegant, tall, and very efficient and liberated young lady. After a slightly shaky start, Bond and Q’ute had become friends and what she liked to call ‘occasional lovers.'”

Markham, P. 26: “In the past, he had often found himself bored by the earnest young men who inhabited the workshops and testing areas of G Branch, but the times were changing. Within a week of her arrival, Frnakie had become the target of many seductive attempts by unmarried officers of all ages. Chase had noticed her, and heard the reports. Word was the colder side of Frankie’s personality was uppermost in her off-duty hours.”

From John Gardner, License Renewed: “In the past, he had often found himself bored by the earnest young men who inhabited the workshops and testing areas of Q Branch, but times were changing. Within a week of her arrival, Q Branch had accorded its new executive the nickname of Q’ute, for even in so short a time she had become the target of many seductive attempts by unmarried officers of all ages. Bond had noticed her, and heard the reports. Word was that the colder side of Q’ute’s personality was uppermost in her off-duty hours.”

Markham, P. 27: “This consisted of a leather suitcase together with a similarly designed, steel-strengthened briefcase. Both items contained cunningly devised compartments, secret and well-nigh undetectable, built to house a whole range of electronic….”

From John Gardner, License Renewed: “This consisted of a leather suitcase together with a similarly designed, steel-strengthened briefcase. Both items contained cunningly devised compartments, secret and well-nigh undetectable, built to house a whole range of electronic…”

Markham, P. 28: “The large, circular smoked glass table which formed a focal point at the center of the room seemed to sink into the carpet, and from there came the sound of splashing water as it gleamed with light to become a small pond with a fountain playing at its center.”

From John Gardner, License Renewed: “The large, circular, smoked glass table which formed a focal point at the center of the room seemed to sink into the carpet, and from it there came the sound of splashing water as it gleamed with light to become a small pond with a fountain playing at its center.”

Markham, P. 28: “Then he saw her, behind the fountain, a small light dim but growing to illuminate her as she stood naked but for a thin, translucent nightdress; her hair undone and falling to her waist — hair and the thin material moving and blowing as though caught in a silent zephyr.”

From John Gardner, License Renewed: “Then he saw her, behind the fountain, a small light, dim but growing to illuminate her as she stood naked but for a thin, translucent nightdress; her hair undone and falling to her waist — hair and the thin material moving and blowing as though caught in a silent zephyr.”

Markham, P. 29:: “They made love with a disturbing wildness, as though time was running out for both of them. The draining of their bodies left the agile Frankie exhausted. She fell asleep almost immediately after their last long and tender kiss. Chase, however, stayed wide awake, thinking back to Korea…”

From John Gardner, For Special Services: “After dining at a small Italian restaurant — the Campana, in Marylebone High Street — the couple had gone back to Q’ute’s apartment, where they made love with a disturbing wildness, as though time was running out for both of them. The draining of their bodies left the agile Q’ute exhausted. She fell asleep almost immediately after their last long and tender kiss. Bond, however, stayed wide-awake, his alert state of mind brought about by…”

Markham, P. 32: “Certainly, they’d seen changes in each other in the fifteen years since then, but the changes were physical. Their minds were as they had always been. Brewster believed in intellect as a force in the world and understood that it could be used only in secret. Chase knew, because he had spent his life doing it, that it was possible to break open the human experience and find the dry truth hidden at its center. Their work had taught them both that the truth, once discovered, was usually of little use; men denied what they had done, forgot what they had believed, and made the same mistakes over and over again. Brewster and Chase were valuable because they had learned how to predict and use the mistakes of others.”

From Charles McCarry, The Tears of Autumn: “Patchen and Christopher saw changes in one another, but the changes were physical. Their minds were as they had always been. They believed in intellect as a force in the world and understood that it could be used only in secret. They knew, because they spent their lives doing it, that it was possible to break open the human experience and find the dry truth hidden at its center. Their work had taught them that the truth, once discovered, was usually of little use: men denied what they had done, forgot what they had believed, and made the same mistakes over and over again. Patchen and Christopher were valuable because they had learned how to predict and use the mistakes of others.”

Markham, P. 32: “They fought as they did, caring nothing about dying, because it seemed obvious to them that dying was the natural consequence of charging an American machine-gun position. Their bravery was an alien form of intelligence, dazzling but incomprehensible.”

From Charles McCarry, The Last Supper: “They fought as they did, caring nothing about dying, because it seemed obvious to them that dying was the natural consequence of charging a machine-gun position. Their bravery was an alien form of intelligence, dazzling but incomprehensible.”

Markham, P. 33: “Chase had never for a moment been blessed with the illusion that he was dead. He had known, touching the muzzle of the Bren with his swollen tongue, that he had not pulled the trigger. He realized, at the moment in which he felt the pain of the blow, that a Korean soldier had crept up…”

From Charles McCarry, The Last Supper: “Wolkowicz had never for a moment been blessed with the illusion that he was dead. He had known, touching the muzzle of the BAR with his swollen tongue, that he had not pulled the trigger. He realized, at the moment in which he felt the pain of the blow, that a Japanese soldier had crept up…”

Markham, P. 34: “He had a facial twitch; his cheek moved, causing the right eye to open like a caged owl’s. Chase had never seen an Asian with such an affection.”

From Charles McCarry, The Tears of Autumn: “He had a facial twitch; his cheek moved, causing the right eye to open and close like a caged owl’s. Christopher had never seen an Oriental with such an affliction.”

Markham, P. 34: “Only the table lamp, fitted with a brilliant photographic bulb, was burning. Colonel Zhao stood behind the lamp in the shadows. He removed a large hypodermic syringe from a leather case, and holding his hands in the light, filled it with an ampoule of yellow liquid.”

From Charles McCarry, The Tears of Autumn: “Now only the table lamp, fitted with a brilliant photographic bulb, was burning. Christopher stood behind the lamp in the shadows. He removed a large hypodermic syringe from the leather case, and holding his hands in the light, filled it with an ampule of yellow liquid.”

Markham, P. 34-35: “Chase sat with one flaccid leg wrapped around the other; his body shook and he wedged his hands between his crossed legs. ‘I want you to understand your situation. It’s possible for you to remain in this room indefinitely. Conditions will not change, except to get worse. No one will find you.’ Chase stopped trying to control his shivering. ‘They’ll find me,’ he said, ‘and when they do, you bastards…'”

From Charles McCarry, The Tears of Autumn: “Pigeon sat with one flaccid leg wrapped around the other; his body shook and he wedged his hands between his crossed legs. ‘I want you to understand your situation,’ Christopher said. ‘It’s possible for you to remain in this room indefinitely. Conditions will not change, except to get worse. No one will find you.’ Pigeon had stopped trying to control his shivering. ‘They’ll find me,’ he said, ‘and when they do, you bastard…'”

And that’s only through Page 17 35. As of Tuesday afternoon, I will have to put my investigations on hold due to several previously scheduled appointments. But I will carry on with my studies upon my return.

11/8/11 PM UPDATE: I have updated through Page 27.

11/8/11 PM UPDATE 2: Jeremy Duns, who did a Q&A with Markham and blurbed the book, offers his apologia.

11/8/11 PM UPDATE 3: It gets worse. Quentin Rowan (aka Q.R. Markham) also managed to dupe The Paris Review. In the Spring 2002 issue (No. 161), The Paris Review published “Bethune Street,” which featured this passage:

Time gives poetry to a battlefield, or some equivalent modern-day gathering at the rim of the awful, and perhaps these St. Luke’s girls were like little flowers on an old rampart where an attack had been repulsed with heavy loss many years ago.

And here is a passage from Graham Greene’s Our Man in Havana:

Time gives poetry to a battlefield, and perhaps Milly resembled a little the flower on an old rampart where an attack had been repulsed with heavy loss many years ago.

11/8/11 PM UPDATE 4: A tip from Sarah Weinman. Rowan also lifted passages in this story “Excellence” — which appeared in the Autumn 2003 issue of BOMB Magazine. Rowan’s passage:

There was a laboratory at Tembleke where a human brain was kept alive in breathwater. It was in a wooden cabinet like an old Frigidaire. I was taken by Provost Man to see it during those days and I wanted to ask questions about it — does it feel, think?

This text was lifted from Nicholas Mosley’s Accident:

There is a laboratory in Oxford where a human brain is kept alive. It is in a wooden cabinet like an old frigidaire. I was taken to see it during these days and I wanted to ask questions about it — does it feel, think.

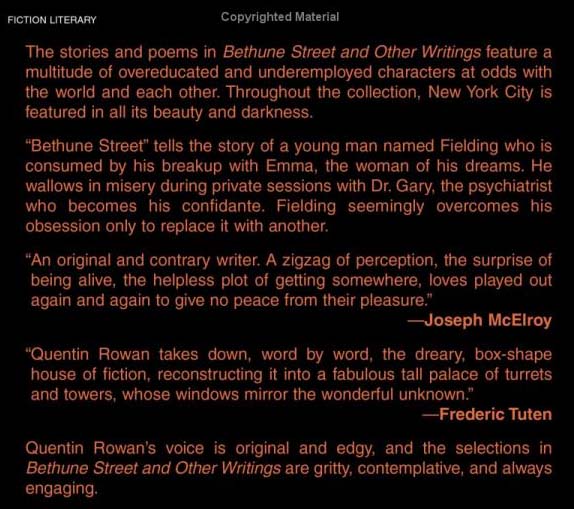

11/8/11 PM UPDATE 5: Here’s a screenshot of blurbs from Joseph McElroy (“an original and contrary writer”) and Frederic Tuten (“Quentin Rowan takes down, word by word, the dreary, box-shape house of fiction…”) from the back flap of Bethune Street and Other Writings, which attest to Quentin Rowan’s “originality.” Note how Rowan is quick to describe himself as “original and edgy.”

11/8/11 PM UPDATE 6: More Quentin Rowan plagiarism. In this apparent essay on Erskine Childers’s The Riddle of the Sands, Rowan has lifted the whole thing from Ralph Harper’s The World of the Thriller. Here’s one small sample.

Rowan: “I have never found the same mixture of sickness and menace in Cold War novels. The rational crime, to use Camus’ term, does not frighten me in the same way as the sick crime. Many of the earliest spy stories still seem the best, and lately I’ve been fascinated by Erskine Childers’ The Riddle of the Sands.”

Harper: “I have never found the same mixture of sickness and menace in cold war novels. The rational crime, to use Camus’ term, does not frighten me in the same way as the sick crime. The early spy stories still seem the best, except for John Le Carre’s; but then he is a very fine writer.”

11/9/11 AM UPDATE: The Guardian‘s Alison Flood reports on the Markham fallout on the other side of the Atlantic. Assassin of Secrets has now been pulled in the UK.

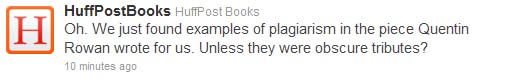

11/9/11 AM UPDATE 2: This morning, The Huffington Post reported:

Sure enough, we see Markham lifting again for “9 Ways That Spy Novels Made Me a Better Bookseller”.

Rowan: “A spy was calm and had a faintly sardonic smile, like Alec Guinness playing George Smiley or Sean Connery eyeing Claudine Auger. A spy might be kind, but in an offhand way as if he were humoring you. Just as – as a bookstore clerk – I find myself talking to customers as if they were children, the spy has no time for your trivial concept of what is real and what isn’t.”

Lifted from Geoffrey O’Brien’s Dream Time: “A spaceman was calm and had a faintly sardonic smile, like Basil Rathbone playing Sherlock Holmes. A spaceman might be kind, but in an offhand way as if he were humoring you. Talking to you like a kid, with your trivial concept of what is real and what isn’t.”

11/9/11 AM UPDATE 3: List updated through Page 35.

11/9/11 AM UPDATE 4: Duane Swierczynski, who blurbed the Markham book, weighs in: “The whole affair leaves me feeling embarrassed, puzzled, and more than a little angry.”

11/11/11 UPDATE: In the comments section at Jeremy Duns’s blog, Duns has revealed that Quentin Rowan responded by email to his request for an apology:

Dear Jeremy,

My apologies for not making an apology sooner. People have told me to wait on writing anyone because I may still be in shock. Also, I just thought I ought to wait for a little perspective to come. I can see how angry you are and know that I deserve every bit of it and more. I promise you that the inside of my head is not a pretty place right now and i am not sitting somewhere enjoying this or laughing about it. There is nothing anyone can say that could make me feel worse than I already do. I am so sorry that I ever got you involved in this mess and would really like to try to explain it all to you. I just can’t do that if you are going to print it or tweet it (for legal reasons etc.) But if we can talk off the record, I will call you back or send a written explanation and fuller letter of apology. Once again, I am truly and deeply sorry, and still remain a great admirer of your work.

With deepest regrets,

Q

This is the first and only known Markham statement after he was unmasked as a plagiarist.

11/15/11 UPDATE: This morning, CBC Radio’s Q was kind enough to have me on their program. I hope to have audio in a bit (I’m typing this while stealing wi-fi), but I wanted to follow up on one question that the excellent Jian Ghomeshi asked me and which I failed to offer a suitable answer for. Jian asked me why wholesale plagiarism of the Rowan variety was wrong. And I offered a rather bizarre lemonade stand metaphor, describing a hypothetical scenario in which a parentless man stole somebody else’s kid, parked that kid in front of the lemonade stand and claimed it as his own, while pocketing all the revenue. Jian then asked me specifically why this was wrong. And I responded something to the effect of “I just feel that it’s wrong.” What I meant to say plainly beyond metaphor — and perhaps I was too dazzled by Jian’s impressive interviewing kung-fu to do so — is that Duchamp’s “Fountain” and Lethem’s “The Ecstasy of Influence” involve clear and traceable sources and thus, in my view, constitute enough transformation of the original sources to become art. I am with Danger Mouse on The Grey Album and with the Random House-cleared edition (that is, sources in the back) of David Shields’s Reality Hunger. In the case of Rowan, he’s essentially stealing labor from other writers in the manner of a robber baron and sharing neither revenue nor credit. And because writers are already underpaid and working long hours for their sentences, I feel this is an especially egregious stance against creative art and creative labor.

11/30/11 UPDATE: The Fix has published an essay by Rowan called “Confessions of a Plagiarist.” While Rowan has not lifted any passages for this piece, it is interesting that he has not apologized, stated plainly that he was wrong, or otherwise offered any form of contrition. He’s getting hammered in the comments.

2/14/12 UPDATE: The New Yorker‘s Lizzie Widdicombe wrote at length about Rowan and was kind enough to include Jeremy Duns and me in her very interesting piece.

© 2011 – 2012, Edward Champion. All rights reserved.

Argh! Thanks for this. It is a shame as I am reading it at the moment and was rather enjoying it! But why did he have to do this? There is no need to plagarise. It just looks like he could not be bothered to write his own story. Very disappointed indeed.

[…] Champion has collected examples of lifted passages. The author’s bio and book have been removed at Mulholland Books, but you can read his […]

I am the son of the late Bond continuation novelist John Gardner, and I was informed and reported this plagiarism yesterday evening:

Apart from Jon Chase being supplied by ‘Frankie’ with equipment identical to that provided by Anne Reilly (in paragraphs lifted intact from Chapter 5 of Licence Renewed), there were other “similarities” as well:

Brewster was a big man, tall, broad, bearded, with an expansive personality— “a big bearded bastard,” Brewster’s secretary and mistress, the petite, blond Tabitha Peters, was often heard to remark. Not the usual kind of person who made it to a responsible position in the clandestine services. They tended to prefer what were commonly called “invisible men”—ordinary, gray people who could vanish into a crowd like illusionists.

Change ‘Brewster’ to ‘Quinn’ and you have the first paragraph of Chapter 4 from Nobody Lives For Ever.

Simon Gardner

Wow, that is staggeringly egregious!

I can’t believe Markham’s editors didn’t catch that.

I’ve read John Gardner’s work, but was not familiar with the other authors. Their prose styles are pretty good. I guess maybe I’ll look up some of the people Markham ripped off.

wow how do they find these – seems like its a needle in a haystack

Wow. I was on here before you updated and couldn’t believe it, but now I’m in shock — and you’re only to page 27. How did his publishing house miss all of this? Not to mention PW, who even mentioned an “Ian Fleming influence.” This makes my head hurt. (However, thank you for your hard work in the documentation.)

Nice detective work, going through and finding the copied passages. Incredible to see what QR Markham has actually done.

“It was the best of novels; it was the worst of novels” And you can quote me on that!

I can’t help wondering how this situation interfaces with some of the canonical tenets of postmodernism, such as hommage, pastiche, and echoing. Isn’t the idea of the total originality of a work of art supposed to be one of the worst fallacies of romanticism? How can any spy novel, or any other type of genre novel, be totally original? Isn’t it possible to view blatant duplication of sentences as a form of irony, an intentional challenge to the obsolete and basically impossible tenets of “originality”?

What is the threshold here? How many plagiarized sentences are allowed in a book of fiction? Of history? Of humor? Is there an exact formula? Or is it merely guesswork? Is one copied sentence sufficient to ban a book? Or five? Or fifty? Is there anything in the Ten Commandments about this? Did the Buddha write a sutra on this subject?

I’m trying to suggest that we’re dealing with a very fuzzy frontier here, where judgments are being made on a case-by-case, ad-hoc basis with poorly defined criteria. Actually it isn’t at all clear to me that artistic considerations are paramount. Instead, the publisher is probably afraid of some kind of legal action being taken by the copyrighted authors that are being quoted. So the situation is not really one where artistic interests are paramount. Instead, publishers are more likely concerned with lawsuits and the judgement of courts and the payment of money.

Thus our high-minded indignation over “plagiarism” becomes merely an obeisance to the literary qualifications of a superior court judge who is much more interested in murder cases. Artistry? Creative integrity? These concepts will receive very short shrift in a court of law.

Isn’t the mere re-use of English words previously used by others a form of plagiarism? The only way an author can evade such accusations is to invent a private and personal language of his or her own. James Joyce tried that, but “Ulysses” is read by very few people today.

Let’s take a look at the classic madonna and child theme in Renaissance art. There are only so many ways of showing a woman holding a baby. Are we therefore to believe that almost all the madonna and child paintings from Renaissance Italy are plagiarized? Maybe so, but is this really a helpful concept in art criticism? How about those endless still life paintings of flowers in a vase? Are they also pieces of plagiarism? Should they be burned? Try that with your Cezannes and Van Goghs!

I’d be delighted to read a spy novel that was 100% plagiarized, with every single sentence blatantly borrowed from previous spy novels. It would be a hilarious tour de farce (yes, the A is deliberate!) and a fine example of the logical postmodernist response to the obsolete romantic notion of “originality.” I realize that for LEGAL reasons, such a book may be impossible to publish. But since when should we alow the lawyers to dictate the types of books we can write and read? That would be merely contemptible, but such is the apparent status quo today. The lawyers rule everything. William Burroughs, are you listening?

We should also note that the very concept of plagiarism is quite recent in literary history, not to mention the concept of legal copyright. And yet there were great masterpieces in the earlier, free-for-all days. Some of those grand old books were almost as good as the James Bond novels. Not quite as good, of course, because they didn’t make as much money. But good all the same. Maybe. Kind of.

Isn’t it wonderful that even today, when every kind of crap and garbage is being published and showered with cloudbursts of dollars, we can still pretend to be so highly moral when it comes to so-called “plagiarism.” Actually plagiarism is encouraged just as long as the relevant legal permissions are obtained. An exemplary case would be the endless parade of new Star Wars novels. The blatant copying of characters and situations from the original movies would be disgusting, except that the formal permission of licensing the product is carefully obtained. And presto! The foul crime of plagiarism becomes a profitable industry when the right signatures are obtained on the proper legal contracts.

It would seem that literary integrity can be bought and sold like lawn fertilizer. Plagiarism? You’re worried about plagiarism? Just pay me the money and everything will be okay.

So if Q. R. Markham had taken the trouble to get permission to satirize the spy novels that he quotes so literally, his book would be a delightful spoof, a “Blazing Saddles” sendup of the worn-out and hackneyed spy genre. Oh, but he didn’t do that, did he? Probably because he didn’t have enough money to buy the rights.

It all boils down to money in the end, and the high and mighty concept of artistic integrity has very little to do with the publishing of books. It’s the dollars, the euros, and the Swiss francs that matter! Instead of defending the integrity of an artist, we’re actually concerned about the profitability of a product.

When you can buy and sell integrity for the right price, IMHO it isn’t really integrity any more. Let the lawyers battle it out! I couldn’t care less.

For all the trouble this has caused, I’m sorry (not that I did it), but this is hilarious.

It’s either a sociopathic level practical joke, or, more likely, a psychological experiment of some kind. Even a degrees of separation experiment – if so, IT WORKED.

Wow.

It reminds me of the effort some students put into cheating. In terms of return on effort they’d be better of just doing the study.

It would take an insane amount of effort to create a mashup novel from so many sources (11 texts in 27 pages and counting). If you’re that well versed in the genre just write a classic derivative story and ship it off to an agent.

Dr. Edwin Poole

You are unreal. You are also a piss-poor reader. Try reading the article again and count the number of passages that were pulled out to illustrate WORD FOR WORD copying.

And all that’s been listed so far is from the first 27 pages of a novel. You know, that big thing with hundreds of pages that count for thousands of words that tell a story.

A novel that people expect to be fresh and original at the very least in the way it’s expressed.

Plots and stories are never truly original. As writers, they take the tried-and-true, put a fresh and original spin on it.

They never, ever, EVER take someone else’s words, copy and paste them and arrange them like some jigsaw puzzle and call that ‘original’.

Copying and pasting someone else’s words is not writing. It’s plagiarism. Your attitude is why high school students seem to have no issue with doing the same for their term papers.

As a ‘doctor’, you really should be ashamed that you’re defending this sort of behavior.

[…] fanfare), and already the jig is up. Then I saw a definitive list of instances put together by Edward Champion. Turns out, I should be reading a lot […]

[…] James Bond novels to titles by Robert Ludlum and Charles McCarry. Edward Champion laid out a staggering series of almost verbatim lifted passages on his cultural website Reluctant Habits, while Duns, author of the spy novel Free Agent, admitted […]

Dr. Poole,

You have absolutely no idea what you’re talking about. There is a legal definition for plagiarism, and Markham/Rowen provably broke it over and over and over. There are no original ideas. It is the expression, not the idea, that can be plagiarized.

The Star Wars novels are not plagiarism. They are allowed (licensed) use of trademarked figures and an established universe. Unlicensed use would be called fan fiction, which is a violation of copyright, not plagiarism.

Dear God, I am stunned. To think that this man actually believed he’d get away with it. Bravo to the editor who had extensive knowledge, who was able to pick up on it.

As a novelist, I can’t imagine trying to imposter another writer.

Valentine deFrancis

[…] Want to know more about the Q.R. Markham (above) plagiarism scandal? Edward Champion is your one stop shop. […]

This sort of thing reminds me of rapper “sampling”, or alternatively, my first effort at a term paper in 9th grade. I vividly recall taking a large amount of material from a NASA publication and stringing it together with my original words, without attribution to the original text. At 13 it is excusable. At “Markham’s” age, it is actionable. (By the way, did he get his nom de plume from the Kingsley Amis pseudonym Robert Markham?) I guess the publisher will soon own his bookstore.

You really can’t compare this to a rapper sampling clips from other songs. For the most part, you recognize the sample from a familiar tune and the artist doing the sampling isn’t trying to pass the samples off as his own. Markham made no attempt to indicate that source of his material came from word for word from other writers.

Edwin Poole’s argument about this being a satirical piece falls flat if you read any of Markham’s other writings. In his piece for the Huffington Post, he specifically refers to writing a “a thriller under a pen name”. That was piece where he lifted a paragraph from Geoffrey O’Brien’s Dream Time.

@Dr. Edwin Poole…

So, how much of you work is plagiarized?

Dr. Poole’s notion of “hommage, pastiche, and echoing” didn’t come out of nowhere, but has been used as a defense for Brad Vice’s “Bear Bryant’s Funeral Train,” his short story collection in which one story, “Tuscaloosa Knights” had portions lifted from Carl Carmer’s 1934 book “Stars Fell on Alabama.”

That book was pulled (it had won a Flannery O’Conner award), but has been republished.

[…] Link to many, many more examples at Reluctant Habits […]

Valentine deFrancis

Posted November 9, 2011 at 10:16 AM

[…] James Bond novels to titles by Robert Ludlum and Charles McCarry. Edward Champion laid out a staggering series of almost verbatim lifted passages on his cultural website Reluctant Habits, while Duns, author of the spy novel Free Agent, admitted […]

To those who wonder how editors didn’t catch this earlier: As an editor who has caught and seen others catch a few instances of plagiarism over the years, I can tell you that catching plagiarism before it goes to press is less like finding a needle in a haystack than it is like accidently getting a needle in your foot while jumping on a haystack. Granted, it seems that there are a lot of needles in Rowan’s haystack. But still.

[…] the problem. James Bond superfans quickly spotted lifted passages. Edward Champion on Reluctant Habits has listed problem […]

[…] James Bond novels to titles by Robert Ludlum and Charles McCarry. Edward Champion laid out a staggering series of almost verbatim lifted passages on his cultural website Reluctant Habits, while Duns, author of the spy novel Free Agent, admitted […]

It is interesting that in the music arena Mash-up albums— Negativeland, Girl Talk, Danger Mouse, The Avalanches—comprised entirely of unaltered music passages that are spliced together to form something new are exalted as quintessentially 21st century art forms.

In the literary arena, a similar endeavor—to piece together something new out of sampled chunks—is greeted with outrage.

At the very least this episode should spark and informed discussion about what would constitute appropriate literary “sampling.” The holier than thou hand wringing accomplishes nothing.

[…] the book and offering refunds. Quentin Rowan (Q.R. Markham) made a habit of plagiarizing – The Reluctant Habit website provides extensive details. […]

[…] investigation which revealed that Markham had plagiarised pages and pages of content. Ed Champion lays out numerous instances of copying up to page 27 but also notes that Markham has plagiarised several other pieces. The US […]

As a writer I am simply astonished that the fool thought he could get away with such a wholesale theft from other books. Still, at least he’s reminding people of some superb authors. Personally I started John Gardner’s THE LIQUIDATOR the other evening, and it’s a delight to dive into the strange life of Boysie Oakes.

poole-

Was this really a satire spy novel, or a spy novel?

Markham was the pen-name used by Kingsley Amis for his Bond novel COLONEL SUN. Quentin’s lack of originality is truly staggering …

@Joshk99: No, it’s not “interesting,” actually. Musical mashups are done with openness and appreciation of the source. There are even literary mashups (e.g. Pride and Prejudice and Zombies) which manage to keep their hands above the table and don’t attempt any deception with regards to source material.

Markham’s novel doesn’t credit its sources, was sold to Little, Brown as an original (in the legal sense) work (else they’d not have pulled it), and is as cut-and-dried a case of plagiarism as they come.

I can imagine how a beginning writer would copy passages from other books to construct a first draft, especially when writing in a genre where originality is not the biggest concern. It seems to me that the author just happened to forget to rewrite those phrases in his own words in subsequent drafts.

How odd.

Edward, thank you for drawing my attention to the fact that Rowan’s guest post on my blog was also plagiarized. I have now removed it, because for obvious reasons I’m not comfortable hosting plagiarized material on my blog – I asked Mullholland to remove the Q&A for the same reason, and removed it from my blog for the same reason, and have stated so in all cases on my blog, so I hope that’s clear.

I think you will soon discover that it is rather tedious to try to find all the plagiarized sentences, because I think every single sentence, near enough, is plagiarized, and as it’s a 278-page novel you’re going to have a very long blog post! For example, you have started your hunting on page 13, but here are just a few from before then, which are some of the examples I sent Mulholland, which persuade them to pull the book.

The foreword of the novel is based on Chapter 2 (titled ‘Spies’) of Dream Time by Geoffrey O’Brien (Counterpoint 2002), with almost every phrases and sentence in it lifted verbatim and rearranged from that source.

Dream Time, p21

‘From end to end, along its fault lines, it’s wired. Impulses respond to impulses. Somewhere deep in the big structures, below ground level, generals at long tables study printouts of sonar readings. ‘

Assassin of Secrets, p3

‘From end to end, along its fault lines, it’s wired. Impulses respond to impulses. Somewhere deep in the big structures, below ground level, generals at long tables study the printouts.’

Dream Time, p19

‘Their life is rhythmically ordered and as perfectly void as a chess game. They glide through space and time, cool and razor-sharp and deeply sensitive to physical surfaces… The air is silent and unchanging. Meanwhile, on the bare screens of the West, there are continual brief weddings of data and expressive form, bouncing off each other like electrons.’

Assassin of Secrets, p3

‘At 1.9 miles per second Keyhole-7’s life is perfectly ordered and void as a chess game. It glides through space and time in a brief wedding where data and expressive form bounce off each other like electrons.’

Dream Time, p21

‘One particular spurt of blips flattening and intensifying might be the wedge that will pry open the self-monitoring, electronically sealed gates of the final launching.’

Assassin of Secrets, p3

‘The stars are silent and unchanging and none of the men below can guess how much this concerns them, any more than they can imagine that one particular spurt of blips might be the wedge that makes an immediate nuclear confrontation possible.’

Dream Time, p20

‘If you could see what the spy sees you would quickly become dizzy. The vertigo of Nick Fury or James Bond falling from a helicopter toward an atomic island is a crude symbol of what you’d feel could you once see the web laid bare: the writhing intertwining unity of all the secret transactions of which the world is built.’

Assassin of Secrets, p4

‘But if you could see what Keyhole sees you would quickly become dizzy. The vertigo of the web laid bare; the writhing intertwining unity of all the secret transactions on which the world is built.’

Icebreaker p54

‘She had changed into a dry black bikini, and the visible flesh glowed bronze, the colour of autumn beech leaves. The contrast of colours — skin, the thin black material and the striking, gold curls cut close — made Rivke Ingber look not only acutely desirable, but also an object lesson in health and body care.’

Assassin of Secrets, p6

‘She had a long aristocratic face that glowed bronze, the color of autumn beech leaves. The contrast of colors — the skin and her striking white blond curls cut close — made this woman not only acutely desirable, but also an object lesson in unblemished, classical beauty.’

Christopher’s Ghosts, p215

‘”Hide and seek,” she said, and rising to her feet she walked down the aisle, swaying with the train and the wine. Her legs were slender like the rest of her — a cyclist’s legs, with visible muscles. At the door she looked over her shoulder, a glance full of meaning.

It was bad form for an agent of the Outfit to permit himself to be picked up by a stranger on a train. Even if this had not been the case, Christopher did not sleep with married women. He went back to his own compartment, undressed, and started to read his novel — Joyce Cary’s The Horse’s Mouth. Soon he came to the page whose number the woman had circled in pencil. It was, he knew, the number of her compartment.’

He combined this with:

Second Sight, p67

‘”The computer whizzes have gamed every possible combination of data — does the kidnapper strike when the moon is full, do his crimes coincide with the anniversaries of outrages against the Arab nation, is he trying to drive us crazy by running an operation that has no plan or purpose? Are you listening?”

“No,” Christopher said.

“I thought not, when you let all those golden opinions go by without a peep.”

“What golden opinions?”

“Never mind. There’s something obvious in this situation, something hidden in plain sight that nobody has seen.”

“Another purloined letter.”‘

To make:

Assassin of Secrets, pp7-8

‘”Hide and seek,” she said, and rising to her feet she walked down the aisle, swaying with the train and the wine. Her legs were spectacular like the rest of her. At the door she looked over her shoulder, a glance full of meaning.

Number One knew it was bad form for an agent of I-Division to permit himself to be picked up by a stranger on a train. He went back to his own compartment and started to read his novel. A moment later he put the book down and thought to himself: It’s been three weeks since the last one was delivered to us. The computer whizzes have gamed every possible combination of data—does the kidnapper strike when the moon is full, do his crimes coincide with the anniversaries of outrages against the Arab nation, is he trying to drive us crazy by running an operation that has no plan or purpose? I need some of Chase’s golden opinions. There has to be something obvious in this situation, something hidden in plain sight. Another purloined letter.

Sometime later he came to the page in his book whose number the woman had circled in pencil. It was, he knew, the number of her compartment.’

Zero Minus Ten, p7

‘With a shout, he leapt in the air and delivered a Yobi-geri kick to Bond’s chest, knocking him back. The blow was meant to cause serious damage, but it landed too far to the left of the sternal vital point target. Michaels was momentarily surprised that Bond didn’t fall, but he immediately drove his fist into Bond’s abdomen. That was the assassin’s first mistake — mixing his fighting styles. He was using a mixture of karate, kung fu, and traditional Western boxing. Bond believed in using whatever worked, but he practiced hand-to-hand combat in the same way that he gambled. He picked a system and stuck with it.’

Assassin of Secrets, p9

‘With a shout, he delivered a kick to the blond woman’s chest, knocking her back. The blow was meant to cause serious damage, but it landed too far to the left of the sternal vital-point target. Number One was momentarily surprised that she didn’t fall, but he immediately drove his fist into her abdomen. That was his first mistake—mixing his fighting styles. He’d been using a mixture of karate and traditional Western boxing, whereas the female had picked a system and stuck with it.’

Second Sight, p468

‘Patchen kept hearing Maria Rothchild’s voice and smelling the smoke from her stinking Gauloises Bleues cigarettes, but he knew these sensations were only a dream. In reality he was floating in a sampan on the River of Perfumes, listening to a tinny phonograph record of a girl singing in Vietnamese. .. How beautifully the girl sang, how the river smelled of the flowers that turned its torpid waters into perfume, how much like his own mind and voice were the mind and voice of Vo Rau! It was uncanny.

Someone seized Patchen’s lower li p and twisted. The pain changed his idea of where he was. Maria Rothchild said, “Wake up, David.” His right eye focused, briefly, and he glimpsed Maria’s face.’

Assassin of Secrets, p9

‘He kept on, though, lunging away, and smelling her stinking Je Reviens perfume, but he knew these sensations were only a dream. In reality they were floating in a skiff down the Seine, listening to a tinny phonograph record of a girl singing in French. How beautifully the girl sang, how the river smelled of the flowers that turned its torpid waters into perfume, how much like his own mind and voice were the mind and voice of this chanteuse! It was uncanny.

Someone seized his lower lip and twisted. The pain changed his idea of where he was. His right eye focused, briefly, and he glimpsed the blond woman’s eyes.’

Zero Minus Ten, p7

‘… Michaels used his strength to roll Bond over onto his back, and, thrusting his forearm into Bond’s neck, exerted tremendous pressure on 007’s larynx once again. With his other hand, the young man fumbled with Bond’s waterproof holster, attempting to get at the gun. Bond managed to elbow his assailant in the ribs, but this only served to increase his aggression. Bond got his hands around the man’s neck, but it was too late…’

Assassin of Secrets, p9

‘She was on top of him now, thrusting her forearm into Number One’s neck, exerting tremendous pressure on his larynx. With his right hand, the American fumbled in his pants pocket, attempting to get at his insurance policy. The blond managed to elbow him in the ribs, but this only served to increase his determination. She managed to get her hands around the man’s neck, but it was too late…’

The Tears of Autumn, p136

‘Afterward, he thought that he remembered the flash of the explosion lighting the flat face of the Chinese boy and the blast lifting the boy’s thick black hair so that it stood on end. The noise was a long time coming. Before he heard the explosion, like the slap of a heavy howitzer, he saw the whole body of the car swell like a balloon full of water. The glass blew out and one door cut through the crowd like a great black knife.

Concussion sent blood gushing out of his nose. He could hear nothing except a high ringing in his ears. All around him, mouths opened in noiseless screams of terror. He lay where he was with his eyes open.

In a few moments a policeman wearing a lacquered American helmet liner leaned over him and spoke. Christopher pointed to his ears and said, “I’m deaf.” He heard nothing of his own voice but felt its movement over his tongue. The policeman pulled him to his feet and led him toward the end of the street. He would have been killed by the fire truck that roared up behind them if the policeman had not pulled him out of the way.’

Assassin of Secrets, p10

‘Afterward, the assassin known as Snow Queen thought that she remembered the flash of the explosion lighting the flat face of the American spy and the blast lifting his thick black hair so that it stood on end. The noise was a long time coming. Before she heard the explosion, like the snap of a heavy howitzer, she saw the whole body of the train car swell like a balloon full of water. The glass blew out and the compartment door cut through the rest of the car like a great black knife.

Concussion sent blood gushing out of her broken nose. She could hear nothing except a high ringing in her ears. All around her, mouths opened in noiseless screams of terror. She lay where she was with her eyes open.

In a few hours a policeman wearing a lacquered French helmet liner leaned over her and spoke. The blond woman pointed to her ears and said, “I’m deaf.” She heard nothing of her own voice but felt its movement over her tongue. The policeman pulled her to her feet and led her out of the debris. She would have been killed by the fire truck that roared up behind them if the Frenchman had not pulled her out of the way.’

I suspect this is not even everything in the first nine pages. I think every sentence, or nearly every sentence, in the book is plagiarized. At a guess, around half of it is from Bond novels – six by Gardner, at least two by Benson – and the other half from at least five McCarry novels (Second Sight, The Tears of Autumn, Christopher’s Ghosts, Shelley’s Heart and The Last Supper), with bits from O’Brien, Bamford and others sprinkled throughout.

I’ve no idea why he did this, other than that he was desperate to be a writer but couldn’t write. I have some ideas on why it passed muster as a novel, which it undoubtedly did, mainly related to structural issues around the genre (see, for example, Umberto Eco’s famous deconstruction of the formula for Ian Fleming’s work), the way we view the Sixties in inverted commas and lot more besides, which would take a thesis to explain, I expect; and I have some ideas on why it was praised so highly, by myself included. But I think I’ve spent rather too much time on this now – and I have a real book I must finish!

Jeremy

[…] plagiarist Q.R. Markham’s temporarily-lauded spy thriller, Assassin of Secrets, is in fact a string of passages lifted from other books in the genre. No-one noticed until it was released, at which time readers noticed at […]

Joshk99, that kind of literary “sampling” is already in use and is actually a trend right now — see Pride and Prejudice and Zombies as an example. The difference here is that the author of PP&Z openly acknowledges the work that he is using and building upon, whereas Markham is trying to pass his plagiarism off as his own writing, giving no credit to the original authors. Similarly, musical sampling also must give proper credit, lest it be sued for copyright infringement.

I bought this book last Saturday. The question for me now is do I return it to the bookstore or keep it as a quirky collector’s item?

Ed, rather than spend time establishing the obvious – that this guy has trouble putting together two consecutive non-plagiarized sentences (though I found an interview with Paul Auster from the NY Post where he somehow accomplished that), you should be looking at the Why.

Quentin Rowan is the son of Lou Rowan, a guy who used to hang out with old Objectivists (Oppen, Zukofsky) and with the St Mark’s Poetry Project people in the ’70s, then went to Wall Street and made a ton of money, then retired and moved to Seattle and published a couple of small-press books (one of which Quentin illustrated – would be interesting to know if he traced those images from someplace) and founded a fairly respected little magazine, the Golden Handcuffs Review.

Is what we’re seeing here some kind of Oedipal trip on the part of the younger Rowan? An effort to prove that all his dad’s lit’ry aspirations, all that saving-up of Street loot to pursue pure art, is all for nought? Enquiring minds want to know, Herr Doktor.

OK, should have said “are all for nought,” or naught, but got some errands to do.

I’m surprised at the shallow and even violent responses to Dr. Poole’s comment above. I don’t think anyone who responded to him bothered to actually read what he was saying, which I thought was very interesting. He wasn’t championing plagiarism, he was suggesting that our mores regarding copying the work of others operate on a sliding scale. Of course someone who tries to pass off so many copied lines and passages as original is a phony, no question. His musing was about the source — and the flashpoint — of our indignation about that copying. It was an exercise in expansive thinking and there was a little hyperbole in it, a thing some of you kids raised on Twitter wouldn’t be able to perceive. I for one found his comment to be worth thinking about. Doc, you have to admit the timing of your comment was bound to win you some flame. Maybe that’s what you wanted?

Is it weird that I’m kind of hurt that I wasn’t one of the writers he lifted from?

Dr. Edwin Poole has plagiarized an essay I wrote 8 years ago almost verbatim. Shame!

O, the humanity….

8^)

“I’d be delighted to read a spy novel that was 100% plagiarized, with every single sentence blatantly borrowed from previous spy novels.”

What you describe is not only permissible, it is explicitly permitted under copyright law. A “parody” can be lifted, word-for-word, from the original, protected source. I suppose Mr. Markham might even attempt to defend his practice as a very obscure form of parody, although I doubt he’d win his case.

You seem to be confused between “plagiarism” and “copyright infringement”, which is understandable; most academicians and lay persons seem to be confused on this issue. There is no legal definition of “plagiarism”; it’s something made up by academics, but has no legal meaning outside a college or university. I have seen “plagiarism” defined in academia in such a way that one could hardly write a romance novel without being accused of “plagiarizing” Shakespeare. There are even professors of English who think one can lay claim to an idea.

“Copyright infringement” is, however, well defined and legally enforceable. It is restricted to the WORD-FOR-WORD copying of text. In the case cited here, Markham is clearly guilty of lifting the work of others word-for-word; in the case of those authors whose works are still under copyright, this is an offense against copyright law and can be called into an action at law.

Your metaphor regarding the works of Renaissance painters is flawed; no painter copied the actual works of Da Vinci or Michelangelo brush stroke for brush stroke (unless, of course, they intended deliberate forgery). They copied the pose, the colors, what have you. One cannot lay sole claim to, much less copyright, an idea or theme or palette. Only the unique physical expression combining unique elements can be protected, and even then only for a few decades. In writing, only the unique use of words can be protected, and even that is subject to judicial judgement. As you point out by inference, there are only so many ways to describe holding a gun or eating an apple.

But as our host points out, Markham used other people’s copyright words over and over, in many places. Whether he gave attribution or not is beside the point; the authors of those works are as entitled to compensation for their use as GM is entitled to compensation for a car it built.

I can certainly understand your concern about our outrage over “plagiarism”; it’s too often used as a stick to beat someone with who is only guilty of accessing a common theme or idea. All too often, the charge is leveled at someone who is only quoting a line or two, or borrowing an idea or scenario. This is legitimate artistic license; as you are clearly aware, there is really no such thing as “originality” in art, and anyone demanding it in their purchases is doomed to frustration. But there is a wide gap between an homage and outright copying of someone else’s unique expression of an idea. I think much of the outrage here is based on the fact that Markham was deceiving his readers, and that’s one thing the reading public will not tolerate.

@Matt

I agree that responses to Dr. Poole’s comment have been at the very least hasty, and I also agree that he brings up some salient points. What I believe some are reacting to, however, is the tone of said post, which could certainly be interpreted as pedantic. This is no excuse for anybody to go off half-cocked, yet if one wishes to further one’s point of view, one might receive more intelligent responses if one doesn’t go out of one’s way to insult the intelligence of one’s audience.

But you know how these kids are nowadays with their Twitters.

Poole’s arguments are childish,uninformed and, sadly, as unoriginal as his Boston Legal name.

Poole claims that the only way an author can escape charges of plagiarism is ‘to invent a private and personal language of his or her own”. He then laments that “James Joyce tried that, but “Ulysses” is read by very few people today.”

Apparently Poole is one of those people, as the ‘private and personal language’ belongs to Finnegans Wake, not Ulysses.

Sarah Stegall just faced everybody. And it was pretty cool.

[…] Champion at Reluctant Habits has a side by side comparison and it looks bad. The comments are interesting, too. They include a further example provided by the […]

Good rebuttal by Sarah, sure enoo’. @Jimmy C., I hear what you’re saying about the pedantic tone and I agree. I mean, people who leave comments on topics like this are usually just spoiling for a fight. I mean, not me. And not you, certainement!. Of course. But people, you know.

Nigel,

I believe you mean Poole is NOT one of those people (who have read Ulysses), but your usage brings up an interesting issue about the “negativeness” of the word few. Does being a part of that “fewness” of people mean you have not read it or that you have? The pedant in me will probably lose sleep over this tonight.

[…] You’re probably aware that Q.R. Markham’s novel Assassin of Secrets, which came out on November 3 in the US, has been pulled amidst charges of plagiarism, and that those charges seem firmly grounded in fact. Here, for example, is Edward Champion’s look at just how extensive the plagiarism actually is. […]

“Dr.” Poole, it’s “homage,” not “hommage.” Or is correct spelling another one of those outmoded tenets?

[…] The damning evidence, assembled by Ed Champion […]

Mr. Markham/Rowan is now my hero. What might have been just another disposable piece of banal commercial trash has now been lifted to the level of art. I’d love to be able to get a copy before they’re all returned and pulped — I’d even like to get it autographed. But by whom?

[…] the most complete rundown, head to Edward Champion’s Reluctant Habits blog. Seriously, just go read it. I’ll […]

@matt

People ruin everything, don’t they? Let’s you and me fight them.

If “Dr” Poole is really a doctor, one can only assume it is not in relation to any form of literature. That fatuous attempt at an “argument” was embarrassingly bad – a first year student would be lucky to avoid failure if they submitted an argument so poorly framed and logically inept.

I am glad that somebody already pointed out the obvious – that Poole was trying to pass off “same subject” as “forgery”.

Embarrassingly amateur.

Q.R. appears to have lifted the name of his hero – Jonathan Chase – from a character late actor Simon MacCorkindale played on a 1980s TV show.

My late father John Edmund Gardner (James Bond continuation author) has had his work plagiarized by Rowan in this so called book. At the last count whole sections lifted from apparently six of John Gardner’s James Bond novels and there could well be more. Gardner is not alone in this either, Raymond Benson (who took over writing the Bond continuation novels when my Father stopped), Robert Ludlum, Charles McCarry, and James Bamford also have had their work stolen, and I am sure as this investigation goes on there may well be more authors work uncovered. This is not like audio sampling which these days permissions are sort first, as hefty expensive law suits of the past ensure that you do not just go ahead and take what is not yours to take in the first place. If Rowan had wanted to do the equivalent of a spy fiction mash up then he should have sort out the permissions, paid for the words and credited the authors their books and their publishers. But no he stole and tried to dupe and make money from publishers and the reading public. And Dr Poole, I have seen the plagiarism with my own eyes and there is no “Irony” I can assure you, the guy is a talentless thief who deserves to be hauled up in front of his peers and account for his abhorrent actions.

Simon Richard John Gardner Hampshire UK

Mr. Markham/Rowan is now my hero. What might have been just another disposable piece of banal commercial trash has now been lifted to the level of art. I’d love to be able to get a copy before they’re all returned and pulped — I’d even like to get it autographed. But by whom?

And this is still available on Amazon:

http://www.amazon.com/Bethune-Street-Other-Writings-Quentin/dp/0595461255

Surprised there are no customer reviews as yet…

@Jimmy C. Agreed. I’ll take the little guy in the corner, you handle the heavies.

@Free Falconer. It’s easy to say what you said (and what lovely words you used) but you give no support for your argument. “Poorly framed”? “Logically inept”? Indeed. How so, exactly? Really, I thought the logic was pretty ept, and as for the framing, well, I could hardly say enough positive things about the framing.

I don’t know “Poole” from Adam’s off ox, but it’s great to get down in a pie fight like this…noting, of course, that republishing others’ work without crediting them or asking permission is really a reprehensible thing. However, only one of many reprehensible things. Hand me that banana cream, will ya?

Judging by the p15 quote, maybe Markham is being autobiographical:

…except attribution. This revelation seems remarkably similar to the recent online prosecution and trial of Johann Hari.

I wonder if publishers will begin to feel the need to use computer-based plagiarism detection software, as used increasingly routinely in academic environments, to compare new manuscripts to the canon of published work. With the increasing digitisation of text driven by e-books, it seems like a natural progression.

If a destitute person liberates an apple from a fruit stand, many are willing to turn a blind eye to such a crime. If an emotionally or existentially poor man borrows some text so he can satisfy his need to have an identity, is that excusable, too?

Changing ideas of authorship should be considered in terms of Occupy Wall Street. An author who refuses to be copied is the same as a totalitarian corporation who pays no taxes. As an author, to be copied is the social tax that must be paid in order to enjoy the fruits of authorship.

What do you think is going to happen when you publish and distribute 10,000 copies of a book to a population of humans who have a biological imperative to copy? Readers will work with their book as they see fit. Some will use them to prop up their furniture, some will copy the stories to their own minds, some will make oral copies as they tell their friends about the plot.

Our moral and legal responses to such behaviors continues to be complicated.

Role playing, mimicking, modeling are vital behaviors for learning, making interpersonal connections, identity formation, meaning-making, and the creation of community. Without mimicry, we would have no relationships, no language and no culture. Heaven forbid a word artist should try to explore these ideas in the commercial market place.

@Dana Spiotta – heaven may not forbid, but copyright legislation does. This was not a learning excercise for the ‘author’. He asked to be paid. He could, presumably, have learned through mimickry just as well without seeking a potentially lucrative commercial publishing deal for his pains. And presumably he also signed a contract whereby he said the work was, in fact, original to him, so he’s hardly the victim here.

@Amazed

Not all legislation is good legislation. Copyright legislation will always be problematic because copying is as much of a biological imperative as sex. Yes there are billions and trillions of dollars at stake when it comes to controlling knowledge, storytelling, and entertainment. But no matter how strict our cultural mores or our laws become, they will never quell hundreds of thousands of years of evolved, ingrained behaviors. You might as well try to make it against the law for your body to replicate cells.

And there will always be people like me who don’t like being told to be a good little reader who only does as he’s told: “Yes, Dana, read these wonderful books. But don’t try to integrate them TOO deeply into your personal experience as a human being, or we will come over there and slap you down faster than you can say ‘censorship sucks.'”

Perhaps we should craft legislation making it against the law to write bad reviews. That would help our authors, right? Or maybe we should create a legislative action strictly limiting the number of books published every year. That would help sales for our favorite authors, right?

In addition to being vital to learning, mimicry is vital to identity formation and maintenance.

What roles do you play in life, Amazed? Do you dress for your roles? Do you use language appropriate to your roles? Do you have props?

I bet you, like anyone, tries to create a nice balance of fitting in and standing out. Do you think an artist might ever be interested in the interaction between fitting in and standing out? Do you think writing is pure expression with no complementary reception? Is writing all yang with no yin? Is reading all reception with no expression? All yin with no yang? Our culture and our laws seem to think so. Is it worthwhile to challenge our culture and our laws?

I think it is, because our cultural mores about plagiarism and our laws are built on ridiculously outdated ideas of authorship, individuality, and creativity. Writing is simultaneously expression and reception. That is where we are headed.

A contract is a prop when one is playing the part of the writer.

Luckily, challenging the status quo is an accepted action for those playing the role of the writer. Or should I say challenging the status quo WAS an accepted action?

The writer challenging the status quo should sign the contract in order to fight our culture’s outdated, unjust theories of authorship and creativity as boldly as possible. They should try to earn a living at the same time, throwing in a little inquiry into the dis-ease that exists between art and commerce.

“Behind every charge of plagiarism is the crazed desire to be plagiarised.” -Marie Darrieussecq

The French can make even IP theory sexy. The person who appropriates is the most careful reader of all. The person who appropriates walks in the shoes of the writer. Takes the writer’s story and plays it on stage as an actor. Pays more and deeper attention to the story than any other reader. That reader’s deep attention in reading is just as vital as the author’s deep attention in writing. Without a reader, an author does not exist. Without appropriation, a story can never be fully understood.

@Tedd

Not siding with Dr. Poole regarding plagiarism and it’s greater context or whatever, but I also keep writing “hommage”, since it’s a French word and for some reason is written “incorrect” in English, all other languages I know write it with double-M.

Come on, join our ranks, let’s infiltrate the English language!

Very interesting, thanks for sharing. Here’s one I hadn’t seen noted before –