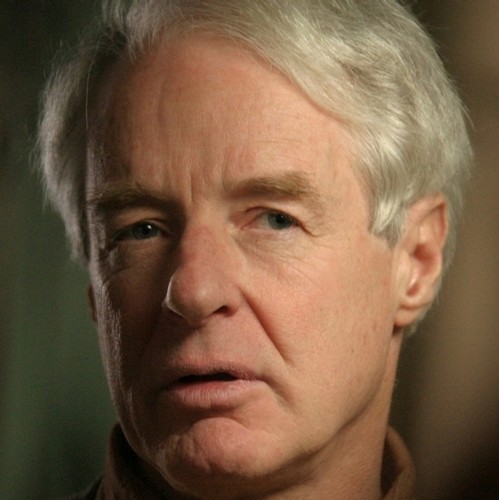

Adam Hochschild is most recently the author of To End All Wars.

Listen: Play in new window | Download (Running Time: 38:08 — 34.9MB)

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Conscientiously objecting and objectifying consciousness.

Author: Adam Hochschild

Subjects Discussed: What is considered morally permissible in war, mustard gas, deadly military technology, Ray Bradbury’s “The Flying Machine,” the women’s suffrage movement and World War I, Emmeline Pankhurst and the Women’s Social and Political Union, splits within the Pankhurst Family, Women’s Dreadnaught, James Keir Hardie’s antiwar speeches, attempts to get socialists to agree, the duties of history to remember the losers, parallels between World War I and current wars, Osama bin Laden’s death, Wikileaks and the Czarist Archives, Margaret and Stephen Hobhouse, conscientious objectors, I Appeal Unto Caesar, Edmund Dene Morel’s hard labor sentence, the tendency of wealthy families and connections to carry more weight, Bertrand Russell, jingoistic writers during World War I, John Buchan’s imperialism, Rudyard Kipling, PG Wodehouse’s The Swoop!, the political stances of writers, contributions of famous writers to British propaganda, The 39 Steps, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes and Germany spy conspiracies, responding William Anthony Hays criticism about “stack[ing] the deck by presenting such particularly unappealing characters as foils to the pacifists and liberals he seeks to praise,” attempting to find positive qualities about Douglas Haig (World War I’s worst general), Winston Churchill, Sir John French’s likable qualities, Haig vs. General Eisenhower, the Lansdowne Letter, attempts to understand why the World War I peace movement failed to catch on, relativistic courage, untrained pilots going up against the Red Baron, and the dangers of speaking out what you believe in.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: It’s an unsuccessful story. Should history really be in the business of remembering the losers?

Hochschild: Well, first of all, for me, as a writer, it was a challenge to see if I could write a narratively interesting and emotionally meaningful story about a movement that failed. My last book was about the anti-slavery movement in the British Empire. That was a successful movement. Slavery did come to an end. These people failed to stop the First World War. But I still find them very, very much writing about. Because it takes a special kind of courage and nobility to go against patriotic madness that’s in the air. And very often, a movement like this, it doesn’t succeed the first time. We still haven’t stopped war today. We’re caught up in at least two unnecessary wars, in my view, in the United States right now. I would like to see people who opposed those wars take some inspiration from these earlier folks. Even though they failed.

Correspondent: On the other hand, I wanted to bring up your recent TomDispatch article, in which you draw parallels between our present times and World War I. I’m wondering if it’s an appropriate parallel simply because in World War I, there was considerably more death. Presently, you say, “Well, why aren’t we protesting the war?” Well, we did in 2003. It was the biggest protest in America against the conflict in Iraq.

Hochschild: Yeah.

Correspondent: So I’m wondering if really the parallels should line up or whether we should consider the full scope of any kind of war when considering it. Is there a danger here of parallel relativism? Or what? Maybe you can expand upon this.

Hochschild: Well, I don’t think the parallels to anything are ever exact or anywhere near exact when there’s nearly 100 years in between. But I guess some of the parallels I saw between the First World War and those that we’re in today are several. First, look at how the First World War started. Austria-Hungary was eager to make war on little Serbia next door. They felt the existence of Serbia was a threat. Because there were a lot of restless Serbs within the border of the old Austria-Hungarian Empire. They had actually drawn up invasion plans to invade Serbia and dismember it. Then Archduke Franz Ferdinand gets assassinated by an ethnic Serb, but an Austo-Hungarian citizen. And there’s no evidence that the top officials of Serbia’s government even knew about the assassination plot. But they immediately used this as an excuse to make war on Serbia. I see some resemblance between that and Bush using the September 11th attacks to make war in Iraq, which had nothing to do with those attacks. So when countries are hungering to go to war for one reason or another, they can easily use something as an excuse. That’s one similarity. I think another is that most of the time when a country starts war, they expect it to be over very quickly and easily. Kaiser Wilhelm II, when he sent his troops off to France in 1914, said, “You will be home before the leaves have fallen from the trees.” And the Germans had this masterplan that they’d worked on for years that very systematically and with great exactitude showed how they were going to subdue France, conquer Paris, and force the French surrender in exactly 42 days. Of course, it didn’t happen that way. But countries always expect it to happen that way. Like when Bush landed on the aircraft carrier in 2003 in front of that big sign MISSION ACCOMPLISHED.

Correspondent: Sure.

Hochschild: Well, I’m still not sure what the mission was in Iraq. But whatever it was, it hasn’t been accomplished.

Correspondent: Well, we just recently had another MISSION ACCOMPLISHED allegedly with Osama bin Laden.

Hochschild: Yeah.

Correspondent: And I’m sure you saw some of the New York Post headlines here. They were really, really grisly. On the other hand, I should point out that there is a fundamental difference between al Qaeda, which is networked all around the world, versus the German nation, which is starving, which is machine gunning the soldiers. And the soldiers on the other side are machine gunning them. And there’s this trench warfare and all that. There’s even a sense of gentlemanly accord in World War I that one doesn’t see in the present conflict. Especially when you also factor in communications. I mean, there’s nothing even close, parallel-wise, to Wikileaks, for example, that you could have in World War I. That’s why I’m unclear as to the parallels. Are the parallels more in the way that governments inform the people and governments persuade the people to become involve in a conflict? Or what?

Hochschild: Well, as I say, the parallels from a hundred years are never completely exact. But there was a sort of Wikileaks episode in World War I, which was this. In 1917, there came the two Russian Revolutions: the February Revolution, when they overthrew the czar, and the October Revolution, when the Bolsheviks seized power in a coup. At that point, the Bolsheviks got into the Czarist Archives and they made public all the secret treaties that Russia, France, and the agreements between Russia, France, and Italy had. That showed how the Allies were planning to divide up the possessions of Germany and its allies once the war was over. And it had tremendous reverberations. In the same way that the Wikileaks material did in recent months. Because it showed that even though the Allies liked the Germans — they were saying they were fighting to defend civilization itself — nonetheless, they’d actually drawn lines on the map as to how they were going to divide up spheres of influence in the Middle East, for example.

Correspondent: Okay. I wanted to shift back to conscientious objectors. The case of Margaret Hobhouse. She’s a well-to-do woman. Her son Stephen is imprisoned as a conscientious objector. This suggests to some degree — this whole incident where she writes a book that is, of course, ghostwritten by Bertrand Russell, I Appeal Unto Caesar — that it takes the rich or the privileged in order to shift things. Because she manages to persuade 26 bishops and 200 other clergyman to sign a statement arguing for more lenient treatment of COs. Similarly, in 1916, some COs are sent to France. They’re fed bread and water. They’re forced to the front line. The No Conscription Fellowship is on the case trying to seek them out. But, of course, because they don’t have this Hobhousian connection, it’s a great difficulty to track these folks down. At the beginning of 1918, there were still more than 1,000 COs behind bars. You have Basil Thomson noticing that pacifism was on the rise. Now this comes after I Appeal Unto Caesar was published. Why was there such a delay between 1916 and 1918 in drawing attention to these maltreated COs? Does it take a book? Does it take a privileged person speaking on behalf of COs to ensure humane treatment for all classes? What of this?

Hochschild: Well, obviously, at all times and places, I think that when the people from wealthy families and so on speak out loudly on behalf of something, their voices carry much more loudly. That’s unfortunately the way the world works. One thing that was interesting to me about the war resisters in Britain was that they came from across the class spectrum. You had people in jail like Stephen Hobhouse, who you mentioned, who was from this very ancient wealthy family filled with connections to lords and bishops and so on. And a very close friend of the family was in the Cabinet — Alfred Milner, who was minister without portfolio on charge of coordinating the war effort. At the same time, there were labor unionists in jail, who didn’t have those powerful connections. And these folks all felt a real sense of solidarity with each other across those class lines.

Correspondent: But was the book really the linchpin? I mean, I don’t want to draw any false correlations here, but I’m curious how this connection to Basil Thomson saying, “Oh, pacifism is on the rise.” Is that more the increased awareness of COs? Or is that more people in grief? Because bodies are coming back. Or they’re not coming back. And they’re getting messages that their loved ones are dead.

Hochschild: Well, actually, the book you mentioned by Margaret Hobhouse, because it was allegedly written by Margaret Hobhouse, who was the wife of a prominent churchman and a big landowner and everything, it had considerable effect. Although in fact Bertrand Russell secretly co-authored it. The book helped bring about the release of several hundred conscientious objectors who were in poor health in one way or another. But that’s about all it did. The government still kept locking up conscientious objectors who refused to do alternative service. It still cracked down with increasing harshness on people who spoke out against the war. Bertrand Russell, despite being himself being the son of an earl; he later inherited the earldom from his brother, was sent to jail for six months in 1918. Edmund Dene Morel, really the country’s leading investigative journalist, spent six months in jail for his antiwar writings. Served hard labor. And it broke his health and he died a few years later.

Listen: Play in new window | Download (Running Time: 38:08 — 34.9MB)