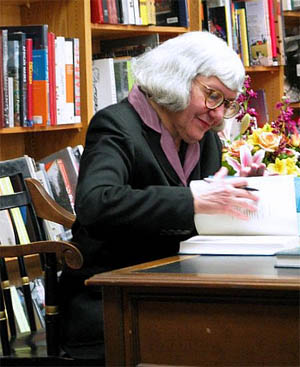

Cynthia Ozick is most recently the author of Foreign Bodies. She previously appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #210.

Listen: Play in new window | Download (Running Time: 56:22 — 51.6MB)

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Wondering why Henry James forces him to have alarming dreams.

Author: Cynthia Ozick

Subjects Discussed: [List forthcoming]

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Ozick: The joy of dialogue. Oh, dialogue! It took me such a long time how to learn how to do dialogue. And I think I learned it from a single book. Which is Graham Greene’s The Heart of the Matter. Which I actually studied to see how he made it concise and dramatic. And I think once you know the character, you have the voice. I suppose you could say that once you have the voice, you have the character. But I don’t think it works like that for me. Once you know the character, you can hear the character speak. And of course, they all speak in their own voices. I don’t know if that’s really related to music. I think that’s more related to seeing. Because you see the character. And if you see visually the character, then if I am looking at you, the voice that comes out of you is naturally yours. Because I see you. Whereas music is this mystery of mathematics. Including Confucius, music and math go together. And that’s a wonder about E.M. Forster. He’s one of the few writers who was very musical. I mean, seriously musical. And that’s in his writing as well. But I think the link with writing is more painting. We see this. It’s so interesting. John Updike had the ability to draw and write. So did Thackeray. Kipling. There are others. I can’t think of them now, but they’re so many linkages in writing and art. In other words, the pen and the eye. Whereas music is abstract math. So that’s where the voices come from. From the eye, I think.

Correspondent: It’s interesting that you mention Greene. Because of course, we know him for the colon. And in terms of looking at your dialogue in this book, what is rather interesting is that sometimes you have almost a Marianne Wiggins-like dash. And sometimes you have the quotes. I’m curious to the methodology behind that. How that developed.

Ozick: Well, that was pretty simple. I needed to have a dialogue in the historic present, so to speak. And dialogue before then. So for the earlier dialogue, I used the dash to distinguish it from the dialogue that’s occurring in the now. Even though the now is in the past tense. Because I have to confess. I have a lot of trouble with our common currency of present tense. Despite those great books of Rabbit [Angstrom]. I was once standing in a group of writers and was so humiliated. Because I mentioned my prejudice against writing in the present tense. And Updike was standing at my right elbow and said, “Well, my Rabbit books are in the present tense.” That was not a good moment. (laughs)

Correspondent: Well, why the aversion specifically to present tense? It’s used a lot more, I think, now than it was thirty years ago.

Ozick: Absolutely. It’s ubiquitous. I don’t know. It just seems that it spoils storytelling. Because it escapes from the magical “Once upon a time.” This happened once. If it’s happening now, then there’s almost no history in it. It destroys the past. And, of course, you see that writers who write in the present tense have to go back and deal with the past. You see that they then have to revert to past tense anyway. And it has a kind of inconsistency. And it’s simply unpleasant to me.

Correspondent: You’re saying that a novel really should present itself almost as a sense of history.

Ozick: Exactly. It’s a story that happened. Not a story that’s happening. And I guess that really needs to be explored. Why should a story that happened be better than a story that’s happening? I don’t know. Help me. Why?

Correspondent: Well, I think when you have a situation like — there was a book by Elliot Perlman called Seven Types of Ambiguity. Named, of course, after the great text. I mean, I like the book. But it has this really absurd situation because it’s written in the present tense. And the narrator’s going, “He’s hitting me.”* When I read this, I thought, “This is just utterly preposterous.” It immediately takes you out of the story.

Ozick: (laughs) Right!

Correspondent: If he “hit” him, right. But “He’s hitting me.” It’s like — wait a minute.

Ozick: Then how can you be writing?

Correspondent: How can I be participating in this? But with the past tense, you can feel a greater sense of participation in the activity.

Ozick: You can believe in it!

Correspondent: Yes!

Ozick: You can believe in it. I mean, it really helps the suspension of disbelief if you present it as a history. And isn’t this the beginning of the modern novel? My Man Friday?

Correspondent: (laughs)

Ozick: We’re supposed to believe that.

Correspondent: Yeah.

Ozick: And we do. Because it’s written like a history. No, I think you hit it when you said it has to do with history. And maybe that is a problem — if there is a problem — with much of American writing today. That it is rather amnesiac.

* — In all fairness to Mr. Perlman, I feel compelled to issue a slight correction. I told Ms. Ozick that I remembered the phrase “He’s hitting me” from Elliot Perlman’s Seven Types of Ambiguity. It has been a good six years since I read Mr. Perlman’s book — sent to me with a handwritten note by Ami Greko, one of the few publicists back in the day to grasp the litblog medium that is now simultaneously ubiquitous and passe. But I can find no indication of the phrase “He’s hitting me” within Perlman’s book. Yet the specific passage I was trying to remember when Ms. Ozick put me on the spot, presented below and written in the present tense, does indeed reveal how the reader can be thrown off when violent gerunds are involved. It still reads as absurd and remains just as applicable to the conversation at hand. This funny little episode also reveals how a fatal expressive error can be misremembered years later, perhaps subject to the same “rather amnesiac” problem with American writing that Ms. Ozick mentions. Authors, take heed when using the present tense!

“I’m going to fucking kill you!” I scream at him. I am punching his face repeatedly, left then right again and again against the smooth stone paving and I am going to kill him. He is squeezing tighter. I am killing him. I am trying to kill him as Anna is pulling me off. She has her arms around my shoulders. She uses all her strength to drag me off him. (80, U.S. hardcover)

(Image: Zugoli Lany)

Listen: Play in new window | Download (Running Time: 56:22 — 51.6MB)

I found Cynthia Ozick’s aversion to present tense interesting. In my opinion, whatever works for the writer is the way to go. In my historical plays, I craft scenes both past tense (narration) and present tense (in the moment). A drama professor at Emerson College tipped me off in the use of “in the moment” play writing. She thought that an audience would get bored if everything was “Once upon a time…” I agree! Layering the narration with a scene shift of said happening to “now” gives a play more depth. I like to give the audience something to chew on. However, just because this works for me, I wouldn’t presume that would work for everyone. Again, the writer should do what works best for her! Indeed, I have one

play entitled “Boston Lockup” which is entirely

written in the present tense!