Ross Perlin is most recently the author of Intern Nation.

Listen: Play in new window | Download (Running Time: 59:27 — 54.4MB)

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Wondering if he somebody signed him up for an unpaid internship.

Author: Ross Perlin

Subjects Discussed: Economic origins of the intern, Gary Becker and human capital theory, how economics contribute to intern culture, humane paid internships and varying definitions of “investment,” spending money to work for free, theological comparisons between internships and indentured servitude, free will and the virtual requirement of internship, Max Weber, the Fair Labor Standards Act, legal exemptions for trainees that permit unpaid internships to run rampant, Walling v. Portland Terminal, “employee” vs. “trainee,” the Department of Labor’s failure to enforce the FLSA, the loss of union and labor power in the last several decades, the six criteria for unpaid interns, why the internship phenomenon is largely white-collar, the many permutations of “perma,” college students who sacrifice considerable money but don’t get the college credit, education institutions who outsource oversight to corporations, the myth of academic credit in college interns, the assumption that college students know what they’re getting into, Lippold v. Duggal Color Projects (link to PDF), Lowery v. Klemm, sexual harassment of interns, discrimination and civil rights, interns forced to prove to the courts that they are legitimate employees before they can pursue grievances, power dynamics between interns and employers, the false sentiment that you can’t be a student and a worker, Marc Bousquet’s How the University Works, addressing correlation between increased wages and economic cycles, unpaid interns as the new temps, how short-term economic logic galvanizes present employment practice, middle-class hypocrisy as epitomized by Benjamin Kunkel, living wage movements, apprenticeships as both a legitimate alternative to internships and “the best kept secret,” the Fitzgerald Act, interns as the subject of cultural ridicule, the complicated class dynamics of internship, being privileged and exploited at the same time, interns and the working poor, the “winner take all” nature of the white-collar world, US vs. UK attitudes about interns, the difficulties of corroborating a secret world, and journalism as the first draft of history.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Perlin: It’s really clear that interns are used to plug holes. They’re used to plug operational holes. They’re used when there’s a hiring freeze. Whenever the wall has been hit in terms of labor costs supposedly for the employer. So that much is clear. In terms of the businessman who says, “Well, economically I can’t pay these people. I can’t do this. I’ve got a business to run,” I would say that is short-term economic logic at best. And at worst, it’s kind of a dangerous move.

Correspondent: Well, elaborate on that. Short-term, dangerous — what do you mean by that?

Perlin: Short-term in the sense that, by every measure, paid internship programs are better than unpaid. And so cycling back to something we had mentioned earlier, taking the long-term view — investing in people, investing in interns, investing in your newest employees in general — is something that has been shown to pay great dividends. To make it more concrete, I mention one example in the book of an employer that saves substantial money through a paid internship program. Because they save on recruiting costs. It’s used as a talent pipeline. Their success metric — something like over 50% of their interns can be hired in full-time roles. They basically calculated that their costs, as opposed to just having to go out and recruit new full-time employees — would be lesser if they could bring people in as interns. Interns are always going to be lower paid than regular employees. The costs are not that great. I mean, if you’re just talking about minimum wage for interns, this is not something which is really going to affect the bottom line that much. I mean, in a huge number of companies, you can have 1,000 interns for the price of one executive. I mean, that is the kind of spread we’re looking at these days in terms of salaries. So a company like this sees the economic sense. They do hire people. So, of course, if you don’t hire people at all, then maybe this sense would break down. But there’s a huge difference between the company which just uses interns on a short-term basis — unpaid. They have access to a narrower applicant pool for their internships. They don’t have access to the widest array of talent. A number of people I talked to reported that when they were going from paid to unpaid, or unpaid to paid, the quality of the people you get changes a great deal. Because if you have a paid internship program, just about anybody can apply, relatively speaking. Also, if you advertise it transparently, if you put it out there kind of like a job more or less, you’re going to have access to a broad talented pool of people.

Correspondent: Well, I was going to say that just having a short-term viewpoint isn’t enough. I want to give you a very good example. It’s right on the cover of your book. You have Benjamin Kunkel. He is one of the editors of n+1. He’s blurbed this book and he’s called it “a fascinating and overdue exposé.” But n+1, they, by the way, have interns who are not paid, who are involved according to the n+1 website with “printing, distribution, publicity, subscriptions, web administration, transcription, carrying boxes, and bartending.” So, in other words, it doesn’t sound all that different from say the Disney College Program or even a government internship, which we haven’t even talked about. There’s even an alleged Twitter feed of the n+1 interns. And I’m not sure if it’s a joke or if it’s actually them. But if Kunkel can commend your book and call it a muckraking exposé, while simultaneously turning a blind eye to the fact that, well, he’s not going to be able to keep n+1 going without his interns, isn’t there a certain hypocrisy in this? I mean, if middle-class society uses and exploits interns, then what hope is there for changing people’s minds? Will they ever even see beyond the short-term? I mean, I agree with you that they probably should. But Kunkel, liberal-minded gent, look at what he’s doing.

Perlin: The publishing industry is one of the worst. It’s one of the worst offenders. The publisher of this book, Verso, has announced, making me very happy, that they have a well-paid, well-structured program. And I know they’re trying to spread that model in the world of independent, even left-wing publishing. But truly this has been an unpoliticized issue that it doesn’t rise to the level of consciousness. All kinds of people who see themselves as championing workers’ rights or who see themselves as liberal completely ignore this issue. Or they figure that all these interns are rich kids. So they can afford it. “It’s not a big deal if we don’t pay them.” Well, that’s an interesting statement. But, first of all, I would uphold the right of everybody to be paid for labor no matter what their background. And so I think to introduce a double standard is actually a dangerous idea. Even though people informally air that kind of opinion all the time. But, second of all, if indeed they are kids born with a silver spoon in their mouth, the question is: Why are those your interns? Well, because they’re the only ones who can afford to work for the non-pay that you’re offering. There probably are some smaller organizations getting off the ground that would have trouble surviving if they didn’t have interns. But in most cases, whether it’s a small liberal magazine in Brooklyn or a startup in the Midwest, whatever it is, they use interns to extend what they can do. To build up their capacity. To try and do more. They do it because they can. Because it’s there. And they haven’t questioned it. And one thing I’m hoping to do with the book is to politicize it such that anybody who wants to get up on soapboxes and say, “This or that is liberal. We should fight for workers. Protect workers and social mobility and social justice and talk about these kind of things,” will also look at their own workplace practices. But this is a much larger issue of people practicing what they preach, right?

Correspondent: Yes.

Perlin: In terms of work. In terms of labor. There’s so often a disconnect. Look at college campuses. Supposed hotbeds of liberalism. You walk into the lecture halls and you have Marxist professors elaborating on this or that. Until a few years ago, and this has only been in a limited kind of area, the people you had actually picking up the trash and keeping a campus running, cooking the food, etc., there was often very little connection between those big picture ideologies which are going on in the classroom and the treatment of those workers. The living wage movement on some campuses tried to rectify that and made a connection, but often you had people on those campuses theorizing about things that were happening in China or around the world, but not noticing the realities of work on their own campuses.

Correspondent: Well, interns — not only are they invisible to even the liberal-minded, but they also are something that people don’t want to see. I mean, you have people who are the working poor who are invisible. What is the solution to making them more visible? They are people too. They have debts they must pay. On the other hand, you also bring up apprenticeships in this book. But even electrician Don Davis tells you that apprenticeships remain the best kept secret. The interesting thing about apprenticeships is that they do pay an hourly wage. Some of them even provide healthcare, pension plans, day care, and the like. Is it really a matter of trying to make people more aware of something that’s secret? And if people in a business become more aware of something like apprenticeships, well, they may very well declare war upon them in the same way that they keep the concept of an intern invisible within their own folds. So do we start replacing internships with apprenticeships? Not necessarily just with books, but with people raising pitchforks in the streets?

Correspondent: Well, interns — not only are they invisible to even the liberal-minded, but they also are something that people don’t want to see. I mean, you have people who are the working poor who are invisible. What is the solution to making them more visible? They are people too. They have debts they must pay. On the other hand, you also bring up apprenticeships in this book. But even electrician Don Davis tells you that apprenticeships remain the best kept secret. The interesting thing about apprenticeships is that they do pay an hourly wage. Some of them even provide healthcare, pension plans, day care, and the like. Is it really a matter of trying to make people more aware of something that’s secret? And if people in a business become more aware of something like apprenticeships, well, they may very well declare war upon them in the same way that they keep the concept of an intern invisible within their own folds. So do we start replacing internships with apprenticeships? Not necessarily just with books, but with people raising pitchforks in the streets?

Perlin: It’s amazing the extent to which apprenticeships — these are trade apprenticeships; blue-collar apprenticeships — are invisible to people who are not in that world, who are not in the trades. Especially in construction, which accounts for generally about 60%. 60% of all apprenticeships are engaged in construction overall. So unfortunately, yeah, if you raised more awareness about apprenticeships, it’s possible that there could be more of an attack on them. That there is legislation relating to it — the Fitzgerald Act, which established a registered apprenticeship program and standards that I see as a kind of model. Again, not incidentally, in the 1930s, as part of the golden age of labor legislation. I think that the reason apprenticeships have remained as they are is because these are generally heavily unionized fields where there are certain standards about what work should look like, what the humane experience is like, and because they work in a longer-term mentality. It’s something that’s been going on for seventy years. And from the employer’s point of view, a lot of employers welcome apprenticeships. And, in fact, the battle often is between the union and the employer over overuse of the apprentices by the employer. Because, even though apprentices are being well-paid and have a lot of benefits, as you say, relatively they’re still cheaper than using a post-apprentice union member worker. Which to me is indicative of the fact that internships would survive quite well, even if there was more regulation. Because again, interns will still represent quite a cheap reasonable solution for businesses to bring on new workers and to accomplish certain work. Even if they have to pay minimum wage, there will be quite a lot of scope for internships.

In terms of raising pitchforks in the street, I think apprenticeships are a real model for internships to look to. But it’s a huge hurdle to bring a blue-collar practice into the white-collar workforce in an era when the white-collar workforce is seen as the norm and the vanguard and setting the standard. It was shocking to me. And I think it’s shocking to a lot of people that here’s something that the blue-collar world is doing so much better. Training and bringing in young people and having a humane program. Invisibility? Yeah. I think there’s an invisibility about labor more generally. Interns are not invisible in the same way that apprentices or the working poor are. They’re featured in pop culture. Everybody sees them around. It’s known who’s the intern. They might wear a certain badge. Like in Washington DC, there’s a particular intern badge everybody knows on Capitol Hill. And people like to talk about interns. And it’s funny.

Correspondent: But they’re also the subject of ridicule.

Perlin: But often that visibility is that they’re kind of a laughing stock and that they’re figures of fun. But I think people do look at interns and they see middle-class kids. They see people who might become them, who they might work with later on. So there’s an atmosphere of civility. And there’s not the class distance often that there is with the working poor or with blue-collar workers, where there’s this feeling like, “Oh, that’s almost the other.” That’s a different somebody else. So that, in itself, represents an interesting problem. The class dynamics of internship are complicated for that reason.

Correspondent: But you’re dealing also with a certain dichotomy of perception. Wisconsin. People are really supporting the unions there. Interns? Not so much. Because of this idea: “Well, they knew what they were getting into.” It’s fascinating to me that there would actually be a strange inverted disparity with the unpaid white-collar worker versus the paid blue-collar worker. Or the paid social services worker. Do you think that’s part of the problem too? I mean, is there any way you can change that cultural perception? Especially since you have it supported not just by media reinforcement, but also by the fact that the U.S. government alone uses a lot of interns in various capacities. And it’s highly competitive. For the reasons we talked about earlier.

Perlin: Well, I think it’s hard to know what the degree of public support for interns is. In the UK, the public has been polled on the issue. And there’s a very strong feeling that interns should be paid. And a very strong majority feels that what goes on now is wrong. In the U.S., it’s hard to know. But I suspect you would still see most people thinking interns should be paid. But there are complex feelings. And I think that part of it is because there is, as you say, a strange dichotomy. Interns are both privileged and exploited at the same time. They’re privileged in the sense that they do have access to this experience that might put them over the top. That they can get into the white-collar workforce. They’re not in as bad a situation, arguably, as people who simply cannot pay to play and will never break into the white-collar workforce.

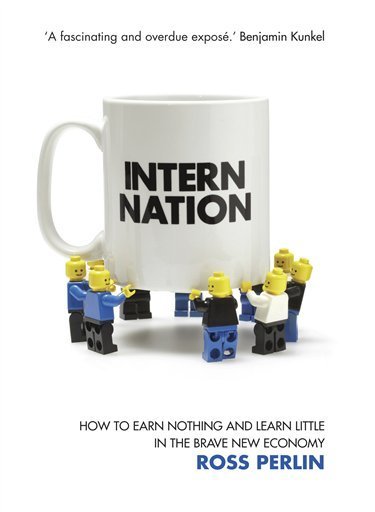

(Image: “The New Interns” by Nik Wilets)

Listen: Play in new window | Download (Running Time: 59:27 — 54.4MB)

As the “hypocrite” n+1 editor called-out above, I’d like to offer both a guilty plea and to place my crime in context. First, the plea: I believe, with the other editors of n+1, that interns should receive payment, yet n+1 doesn’t at the moment pay its interns. This makes me a kind of hypocrite, true. But the host’s suggestion that the n+1 intern program differs little from that of the Disney Corporation seems disingenuous; and Ross Perlin’s assimiliation of n+1 to “the publishing industry” also seems off. The publishing industry is dominated by giant for-profit multinationals, with paid leadership and main staff, as well as book advances for authors. n+1, by contrast, is a tiny non-profit foundation subsisting through volunteer labor. We employ precisely two paid staff. The magazine’s editors receive no compensation for their work. Writers for our website and authors of reviews for the print magazine likewise go unpaid. (Contributors of longer pieces, except when they are editors of the magazine, receive honoraria of several hundred dollars.) Governments and corporations can afford to pay interns a living wage. n+1, as yet, can afford to pay only two salaries. Both go to former interns.