There was a time not long ago when I was a booster of all things Werner. Here was a man who contended with the twin terrors of Klaus Kinski and Bruno S. – the former was given a fascinating documentary, My Best Fiend – allowing them to explode into mad rages on set. He had stolen a movie camera to get his career started. He had moved a boat over a mountain. He had been shot during an interview and carried on talking. For Little Dieter Needs to Fly, he explored a Vietnam vet’s experience of being tortured and starved by hiring Laotian locals to tie him up and recreate the experience. Herzog was a bona-fide original, a maverick devoting decades of his life pursuing the perverse and the idiosyncratic.

But my feelings on Herzog changed a few years ago when he decided to rethink Abel Ferrara’s masterpiece, Bad Lieutenant, without respecting the artistry of the original. Ferrara wasn’t pleased. “I wish these people die in hell,” said Ferrara at a press conference. “I hope they’re all in the same streetcar, and it blows up.” Herzog replied, “I have no idea who Abel Ferrara is. I’ve never seen a film by him. Is he Italian?” This seemed out of character for a man who had gone out of his way to chronicle the misfits and the misunderstood. Surely a man as thorough as Herzog would have checked out the original film before signing on. While the resulting film, Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans, had its moments, it served as a sad concession to the sausage factory. Herzog had at long last gone part Hollywood. David Lynch helped Herzog make My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done? with schlocky results. And now we have Cave of Forgotten Dreams, a 3D documentary about the Chauvet Cave.

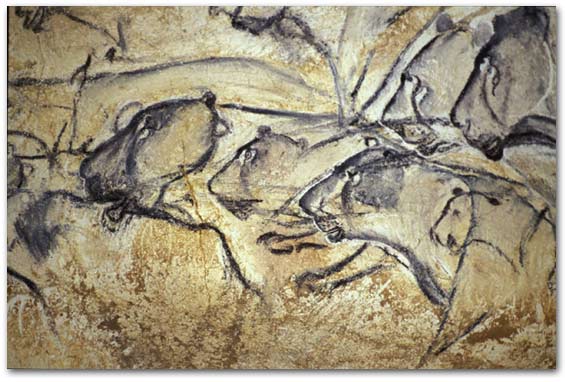

The Chauvet Cave, a subterranean treasure trove of Paleolithic paintings discovered in 1994, is a near foolproof subject for 3D. The paintings depict now extinct panthers of which there is scant trace of fossils. There are depictions of Venus-like figures, along with striking perceptive shifts created by the cave dwellers over time. The cave itself has been sealed off from the public to prevent Lascaux-like destruction. Film is the only way in which we’re likely to see it. That Herzog managed to get what he did, when he was limited to staying on the paths and when he could only shoot for four hours a day, is a testament to his tenacity. Sure enough, the dripping calcite compounds, the plentiful passages, and the stark stalacites framing the cave art certainly inspire a genuine sense of awe as you’re wearing the glasses.

The problem here is that we’re dealing with the post-Bad Lieutenant Herzog, a carnival barker more interested in badgering us into wonder rather than seducing us into how people live. Herzog is the type of narrator who compelled to boom “How did they live?” multiple times while the viewer is trying to form her own impressions of the art. And this becomes an annoying intrusion. I mean, imagine that you’re staring at Guernica and some intense German sneaks up behind you and keeps saying, “Do you see how great this is? Do you see how they died?” You begin to wonder if it’s possible for some authority in Madrid to issue a temporary restraining order so that you can rid yourself of the creepy man who wants to get inside your pants but won’t take no for an answer. That Herzog’s overbearing narration comes with bad Baywatch jokes doesn’t help matters. Who knew that Herzog was the Paul Reiser of tour guides?

Because Herzog’s approach is so corny and melodramatic, it takes away from some of the film’s more successful quieter moments, such as the former circus juggler who turned archeologist and another expert who presents a reconstructed ivory flute and who speculates the type of music our ancestors were likely to play.

Given how Herzog fabricated aspects of Bells from the Deep, hiring two drunks to stand in as pilgrims, these over-the-top moments shouldn’t come as much of a surprise. But given that this is a film professing to explore the nuances of artistic eloquence, such an artless approach is severely misplaced. Cave of Forgotten Dreams feels like one of James Cameron’s narcissistic explorer documentaries rather than something that can stand toe-to-toe with Grizzly Man or The Dark Glow of the Mountains. Herzog had the rare, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to chronicle some of the oldest art on this planet. I was left asking myself, “I have no idea who this new Werner Herzog is. Is he an artist? Or has the old Herzog left us for good?”