Kate Tuttle is an unremarkable corporate windup doll who writes about books much in the same way that moribund losers sign up for macramé classes to make friends: namely, deadening the room with dull and desiccated sentences, life-sucking generalizations, and all the lack of adventure that you see in some uptight and hopelessly white suburbanite who upturns her nose at any dinner entree with a touch of paprika. I’ve stayed silent about this toothless husk for many years. There was really no reason to care. Because I tend to ignore those who couldn’t write an original thought to salvage their sad and spent lives. Indeed, my only contact with this miserable batbrain over the great epoch of my Molotov-throwing existence was to ask her to pass along my thanks to her far more accomplished husband for mentioning me in his truly excellent book, Bunk. But that was only because I didn’t have the dude’s email. I don’t think that is the sign of an “asshole” — I’m sorry, “noted asshole,” to evoke Tuttle’s panache for unoriginal vitriol. Then again, the literary world is so dull and gutless, so casually resentful towards any talent who sticks out, that they feel an overwhelming and deranged need to summon me every so often — despite all the long debunked canards about me — into the role of the dependable heavy.

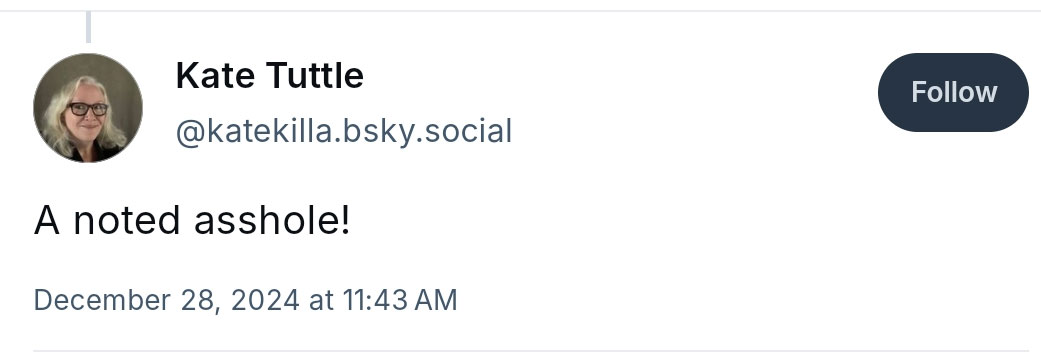

Well, now that Tuttle has called me a “noted asshole”– this when I tend to be kind and congenial if you meet me in the streets — I feel that I have a responsibility to live up to the ridiculous moniker by finally exposing this hideous charlatan, who is better suited to banging out press releases in between suicidal ideations. Largely because I very much subscribe to what Sean Connery once identified as “the Chicago Way” when it comes to settling scores with insignificant and unsmiling fuckwits who write with the absent gusto of someone who is permanently dead inside. If she had simply said nothing, the fireworks you are about to see would not have been written. Consider this a caveat to any other corporate media dullard who wants to start shit with me.

To get a sense for how this desperate gasbag pads out her “pieces,” one can look no further than her review of Abigail Thomas’s Still Life at Eighty:

She does worry about the state of her memory, as perhaps everyone her age does. “My memory is full of holes,” she notes, and later asks, “Does losing memories presage losing my mind?”

Yes, Tuttle really does thinks this little of her readership. Despite the cited quote already establishing that Thomas worries about her memory, Tuttle feels the need to spoon-feed this in the most insultingly condescending terms, even though anyone with a sixth grade level of education could decipher this obvious point on his own. And Tuttle is so artless a writer that the word “worry” appears seven times in an 800 word review.

Tuttle’s proclivity to repeat herself like someone suffering from palilalia is also prominently featured in this Mina Javaherbin profile:

Children’s book author Mina Javaherbin is an architect as well as a writer, and her latest book was largely inspired by the architecture of her father’s hometown, Isfahan, Iran.

Kate Tuttle is a critic who criticizes books in works of criticism! (Uses of “architect” or “architecture” appear five times here. And this senseless snippet is under 400 words.) Was there some internal memo within the Globe ordering its staffers to repeat words like this to court the departing eyeballs?

In fact, Tuttle is such a careless hack that she can’t even match proper tense in a lede: “but everywhere she turns there’s another obstacle — including some that might be deadly.” Boston Globe, this is the “editor” you’ve kept on board to run your books section? Indeed, Tuttle is such an incurious bean counter that a thoughtful dude like Alex Segura is reduced to spouting generalizations hammered in by media training: “It felt like an interesting challenge.” And in interviewing Jodi Picoult on the vital topic of book bans, Tuttle never once brokers anything other than general questions, which is a significant insult and a trivialization toward an author needlessly censored by fascist (and often sexist) zealots. In rightly commending Rebecca L. Davis’s fearless work, Tuttle describes her “well-turned and crystal clear explanations.” (Tuttle can’t seem to pick a lane when only one modifier offering the same meaning will do.)

And if you think that Kate Tuttle is a champion for women writers, consider the crass way in which she belittles Jami Attenberg for writing “a longer timespan than she’d used in previous novels.” Now I’m obviously no fan of Jami Attenberg. But I would never denigrate a writer like this. A writer who flexes her wings and attempts ambition shouldn’t be singled out like this. Would Tuttle have made the same pronouncement if Attenberg were a man? Perhaps this was an aloof attempt at gender parity. But three women who I read this passage to on the phone this afternoon (I did not tell them that a woman wrote this until after they answered) all told me that this came across as patronizing.

I may or may not be an asshole, “noted” or otherwise. But I can tell you this much. I actually write in a voice that you’ll fucking remember. Kate Tuttle will continue banging out these hopeless platitudes and lackadaisical gaffes, but she has failed to grasp that well-behaved women never make history.