Ben Tarnoff is most recently the author of The Bohemians.

Author: Ben Tarnoff

Listen: Play in new window | Download

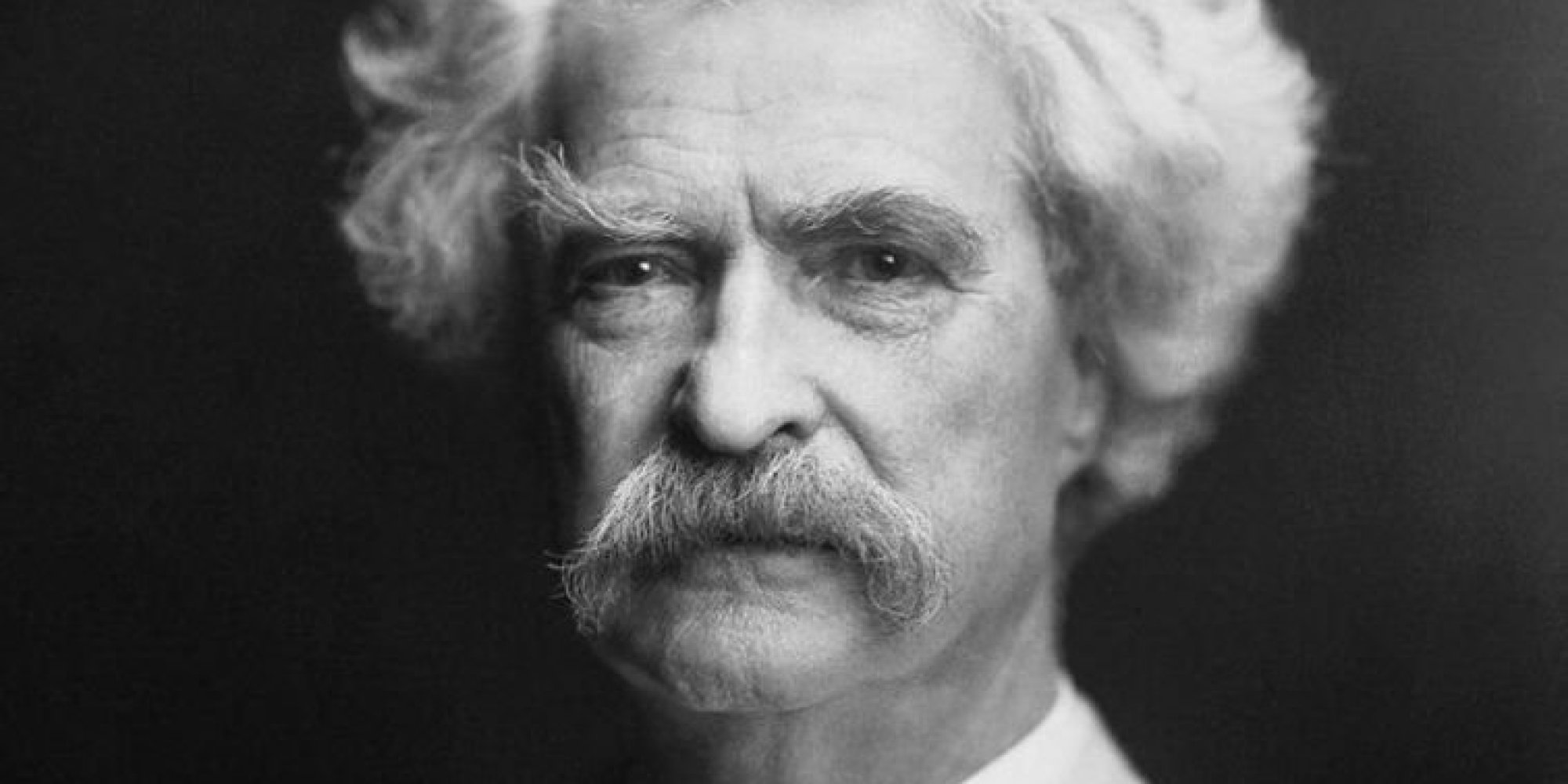

Subjects Discussed: Why 1860s California was especially well suited to literary movements, draft riots, Thomas Starr King, how Atlantic Monthly editor James Fields interacted with numerous emerging writers, the New England influence vs. the need to rebel, Charles Stoddard, rustic towns vs. cities battling each other in California over poetic merit, Bret Harte’s aesthetic tastes, how Harte transformed from critic to short story pioneer, how Mark Twain used the door-to-door subscription model to popularize The Innocents Abroad, the influence of the railroads upon what people read, Twain’s inability to command literary respect in America during his time, Twain’s popularity in England, the disreputable qualities of Twain’s appearance, Twain’s drawl, William Dean Howells, the Eastern literary establishment’s regressive assessment of Western style, how Twain used the lecture circuit to generate vital income, early standup comics in America, Artemus Ward the first standup comic in America, New York’s emergence as a media capital in the late 19th century, the development of Twain’s iconoclasm, present day interpretations of Twain as a cuddly avuncular type, Twain’s explosive temperament, Twain’s failed attempts at suicide, how original literary movements can spring from a unique location, present day Brooklyn writers who play it safe, how Twain’s lecture persona allowed him to escape becoming a newspaper hack, Twain vs. Ed Koch as meeter-and-greeter in the streets, the Bret Harte/Mark Twain friendship and feud, Bret Harte’s creative decline upon leaving California, Margaret Duckett’s Mark Twain and Bret Harte, the mysterious inciting incident in 1877 that set Twain off on Harte, Twain’s difficulties in getting his early short story collections published, the death of irony throughout American history, disparaging reports of Anna Griswold Harte (and attempts to find positive qualities about her), how much Bret Harte is responsible for Anna’s alleged sullenness, Bret Harte’s arrogance, Harte’s abandonment of his family, Harte’s aristocratic airs, Harte’s insistence upon a cab when arriving on the East Coast, Bret Harte’s hipster-like sideburns, “Ah Sin,” Twain and Harte perpetuating racist Chinese stereotypes, Twain selling out his principles, yellowface and the Cloud Atlas movie, Twain’s unremitting vengeance against Bret Harte, Twain’s obsessive detail in depicting his grudges, Twain’s tremendous rage and his tremendous love, Twain blaming himself for the death of his son Langdon, parallels between Charles Stoddard and Walt Whitman, Stoddard’s need for approval, Stoddard seeking autographs, Stoddard’s retreat to Hawaii, attempts to determine how much transgressive behavior there was in San Francisco during the late 19th century, Bret Harte rebuffing his literary friends when he moved to the East Coast, Ina Coolbrith as the first woman poet laureate in the United States in 1911, Coolbrith’s “When the Grass Shall Cover Me,” the crushing domestic responsibilities faced by Coolbrith (and stalling Coolbrith’s literary career), grueling library hours in the late 19th century, Stoddard’s South-Sea Idyls, Harte’s remarkably swift dissolution, Harte’s inability to take root in the East, Ambrose Bierce, whether Bierce arrived too late on the scene, pulp writers who lived at the Monkey Block in the early 20th century, Fritz Leiber’s Our Lady in Darkness, and whether any literary movement today can recapture the risk-taking feel of the Bohemians.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: Mark Twain and Bret Harte seem to be the big stars of this book. But what do you think it was about this particular area at this particular time that created this particular literature?

Tarnoff: Well, San Francisco in the 1860s has a lot of advantages for a writer. It’s peaceful. The Civil War never comes to California. So there’s no fighting on the coast and there’s no draft. Because Lincoln never applies the draft west of Iowa and Kansas.

Correspondent: And no draft riots.

Tarnoff: Right. Exactly. No draft riots. So it’s peaceful. It’s a great place to wait out the war. It’s very rich. Because it’s the industrial, commercial, and financial center of the region. So the massive amount of wealth that’s being generated in the City finances a range of literary papers. And it’s also very urban. It’s got about 100,000 people in the 1860s and that makes it by far the biggest city in the region, really the biggest city west of St. Louis. And that population is pretty cosmopolitan. Because of the legacy of the gold rush, you have people there from China, from South America, from all different countries in Europe. And I think that all of those are important factors behind producing the literary moment.

Correspondent: And for a while, speaking of St. Louis, it had the largest building west of St. Louis with City Hall.

Tarnoff: That’s right.

Correspondent: For a while. Until it got — I can’t remember which building it was that actually uprooted it. But it was a city of great progress and great buildings. I wanted to start off also by getting into the preacher Thomas Starr King. He’s this figure I have wanted to talk about forever. Because I have read, I’m sure as you have, the Kevin Starr books. The wonderful California Dream series. I’m grateful that your book has allowed me a chance to talk about him here. You know, it has always seemed to me that without King, you could not have had the literary culture that emerged. Because he was this really odd figure. He promoted New England writers. So he was kind of an establishment guy. But at the same time, he’s also the guy who introduces Bret Harte to James Fields, the Atlantic editor, in January 1862. Charles Stoddard — this wonderful poet — also held King up in great esteem. So he’s almost this insider/outsider figure who seems to corral the many literary strands of San Francisco that are burgeoning during this time and forming this new kind of movement that you identify as a Bohemian movement. So I’m wondering. What is your take on Thomas Starr King? Do you think that San Francisco would have been San Francisco if it had not been for that? And do you think that when The Overland Monthly appeared, that this was kind of the replacement for Thomas Starr King? Because at that point he had passed away. What of this?

Tarnoff: Well, Thomas Starr King is a fantastic figure. I think he really is a forgotten founding father of California. He’s so foundational politically, culturally, as you point out from the literary scene. He’s a fantastic mentor figure. You mentioned Charles Stoddard. There’s a scene in my book where Stoddard has just published his first poems in a big literary paper. He’s extremely shy and nervous. And Thomas Starr King comes to the bookshop where he works and tells him personally how much he loved his poems. So he’s a guy with a really personal touch and really cultivates these writers and offers them criticism. He’s an important figure from the point of view from the point of view of the Civil War as well, which is I think how he’s better known today. Because he travels throughout the state during the first year or two of the Civil War and preaches the importance of California staying in the Union. Which it probably would have stayed in anyway. But King is certainly a very persuasive champion of the Union and of abolition.

Correspondent: Yeah. But in terms of his literary contributions, I mean, he was again, like I was suggesting with this last question, this guy who was there to rebel against and this guy to garner favor with so you could actually get into some of the outlets. How did that work? Am I perhaps overreaching with my estimation of King as this great mirror that Twain, Harte, and all these other people looked at in order to find their own voices? To find their own particular perch to break into San Francisco journalism, literature, and all that?

Tarnoff: Well, I think he builds a link between the Eastern literary establishment and San Francisco. You mentioned his introduction of Harte to James Fields, the editor of The Atlantic Monthly. He also is friends with Longfellow and Emerson and all these literary lions who are really the most famous writers in the country at that point. And he gives these wonderful lectures on American literature in San Francisco. So he absolutely is a link between the East and the West. But he’s also someone to rebel against. I mean, he’s the father figure. You’re also trying to kill your father. And a lot of these guys — particularly Harte — you see him strain from that New England mold. Thomas Starr King sadly dies in 1864 young and prematurely. And in the coming years, Harte really develops his own style, which I think contrasts pretty sharply with those New England influences.

Correspondent: So what was essentially taken from King and even the New England influence? What made this particular area of the country the natural place to establish new voice, original voice, a rebellious voice, an iconoclastic voice?

Tarnoff: Well, Thomas Starr King has this great phrase in one of his sermons where he tells Californians they need to build Yosemites in the soul. And his point there, I think, is that they’ve been blessed with this majestic epic monumental landscape. This incredible natural beauty. And they need to create a culture and a literature, an intellectual scene, that’s commensurate with that great beauty. And the Bohemian scene really takes that advice seriously. And the West, I think, is such a fertile place for a new type of literature to develop. Which really does deviate from the path that King himself had hoped it would take. I mean, he wants California to follow closely in the footsteps of New England. He has a letter where he says California must be Northernized thoroughly by Atlantic Monthlies, by schools, by lecture halls. But the scene that he mentors after his death really takes things in a different direction, but I think makes good on his command to build Yosemites in the soul.

Correspondent: Well, it’s interesting how we’re talking about the variegated territories of California. Because Bret Harte would edit this poetry anthology and get into serious trouble. Because some of the rustic towns didn’t like the fact that they weren’t included. And he was flummoxed with all sorts of poetry entries for this thing. And he ended up choosing a lot of poems that dealt in the metropolises. So there was this rivalry and Harte was accused of being this florid sellout by some of the rustic towns. You point out in the book that actually the metropolises and the rustic towns and the mining settlements and all that had actually far more in common than they actually realized. So what accounts for this fractiousness and territorial temperament? Fractiousness in literary voices and literary temperament?

Tarnoff: Well, California’s a place where everyone wants to be a writer.

Correspondent: Like Brooklyn today!

Tarnoff: Right. Exactly. It’s like Brooklyn in 2014. But poetry in particular has a real prestige. Poets are pop stars. Poems are read at every public gathering. You need poetry in the public sphere all the time. And so all of these Californians — people who live in the countryside, people who live in the city — all think of themselves as a poet. So when Bret Harte is tasked with putting together a representative anthology of California poetry in 1865, he is overwhelmed with submissions and has a lot of fairly sarcastic, disparaging things to say about the quality of those submissions and ends up producing this fairly small volume with mostly his friends, like Charles Stoddard and Ina Coolbrith. And this ignites a kind of literary war between the city and the country. But as you point out, the distinction between the city and the country is not actually that great. I mean, the California countryside in terms of the mining and the farming operations is itself pretty heavily industrialized. We’ve got big economies of scale, a lot of heavy machinery. Places like Virginia City, in Nevada, where Mark Twain is for a few years, are highly urbanized areas. So the notion that it’s these kind of he-men in the frontier vs. the effete Bohemians in the city, it’s not totally accurate representation.

Correspondent: Well, in this sense, you’re essentially saying that the sphere of influence in both rustic town and big city is essentially homogeneous. That people are perhaps being inspired from the same physical things? I mean, what of literary tastes? What of the way that people express themselves? I mean, isn’t there an argument to be made that maybe these guys were right?

Tarnoff: Well, there’s certainly a distinction in terms of literary taste. I mean, I think both camps are living fairly urban industrialized lives. But they certainly have very different opinions about what constitutes good poetry. And Harte in particular, who is the editor of the volume, shies away from topics that he feels are too pastoral. That have too much of a certain type of California flavor, which he associates with the amateur poets. And he writes a parody of what one of those poems would look like in The Californian, which he edits. But Harte really wants to push California literature in general to a more metropolitan, to a more Bohemian, to a more sophisticated level and is very dismissive of what he feels is the kind of amateurish literary karaoke quality of some of the countryside poets.

Correspondent: Well, what is that sophisticated nature that Harte is demanding? What are we talking about? Are we just talking about endless poems devoted to being in the middle of nowhere? Essentially that’s what he’s railing against? He’s asking California to take itself more seriously, to write about civil, social, political topics? What are we talking about here?

Tarnoff: Well, the problem with Harte in these years — the mid 1860s — is he’s very good at being a critic. He’s very good at lambasting the quality of California literature, at its climate, at its boosters and philistines and capitalists. But he’s not great at producing good literature of his own. And that comes a little bit later in the decade when he starts to write these wonderful short stories. “The Luck of Roaring Camp” being the best known. And it’s not until that moment that I think he really makes good on his earlier promise to redeem California literature.

Correspondent: So he’s essentially quibbling with what he doesn’t like in order to find out what he does like and what he can actually build from the ashes he demonizes, so to speak.

Tarnoff: Exactly. He’s definitely in a more critical phase at that moment.

(Loops for this program provided by Martin Minor and nilooy. Also, Kai Engel’s “Chant of Night Blades” and Kevin MacLeod’s “Ghost Dance” through Free Music Archive.)

The Bat Segundo Show #541: Ben Tarnoff(Download MP3)