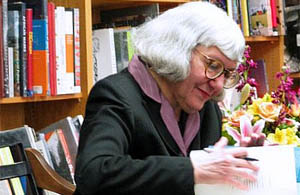

David Rakoff recently appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #362. Mr. Rakoff is most recently the author of Half-Empty. He previously appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #167 and The Bat Segundo Show #168.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

PROGRAM NOTE: This show contains many unusual moments: the unanswered phone calls ringing in Mr. Rakoff’s apartment, the race to the Internet to look up the word “vitiate,” the efforts by both gentlemen to assign various forms of depression and optimism to each other, the common counting mistakes (listen carefully to the intro), and Mr. Rakoff opening up a window. Since these flubs and quirks are presented here unadorned for the listener, we must offer at least one correction. Our Correspondent mangles a George Bernard Shaw late into the conversation. The correct quote is “The real moment of success is not the moment apparent to the crowd,” and comes from Caesar and Cleopatra.

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Confusing threes, fours, and fives.

Author: David Rakoff

Subjects Discussed: [List forthcoming]

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: You just mentioned that you will not delve into certain aspects of your life in writing these essays.

Rakoff: For the most part.

Correspondent: For the most part. This leads me to wonder about “Shrimp.” The essay in which, as a child, you report that you have a desire to have a fast track to adulthood. This led me to wonder if you had even really attempted to view this from the reverse vantage point. Of you as an adult reporting back to David Rakoff the child, “Okay. Here’s what it’s all about. It’s perfectly okay.” You say you have a happy childhood. But you also have this longing to become an adult very, very rapidly.

Rakoff: Yes.

Correspondent: As a quick rung up the ladder. That’s just not the way life works. Why view it from this linear quality? This is interesting because you are often very digressive in your essays.

Rakoff: Yes.

Correspondent: Which is why I like them. But from this vantage point, from childhood to adulthood, you’re looking at only in one direction and not really the reverse. I’m curious why that was. Or if you have made attempts to look at it the other way. Or is that where the essay “Isn’t It Romantic?” comes into play? Is that you — okay, here’s the adult looking back to being a child.

Rakoff: Wow.

Correspondent: Just to throw some things at you.

Rakoff: Okay, let me see if I can parse this into something resembling an answer. Part of the reason that I don’t look back — or, you know, look in reverse — is twofold. I’m really not kidding when I said I didn’t enjoy being a child. So I don’t really adore remembering that. I’m not comfortable with who I was. I’m a little embarrassed with who I was. So I don’t spend a lot of time looking back. And also because I don’t generally try to mine my own life. It feels a little — I’m still not entirely comfortable with what seemed to be a certain sort of self-mythologizing aspects I’m not just comfortable using the details of my life. Although it’s a somewhat waffling response. Because this particular book is full of details about my life and things that are quite personal, I suppose.

Correspondent: And possibly the most personal of the three books.

Rakoff: Oh, undoubtedly the most personal of the three books. Yes, absolutely. But in terms of the forward-looking thing, there is that anxiety that marks whatever phase you’re at. And I think it’s an anxiety that marks life in general. Which is: Everything takes longer than you hope it’s going to. Everything. Everything has to gestate. Whether it’s work, whether it’s creativity, whether it’s just having people in the world knowing who you are and therefore throw work your way. It’s always, “Everything takes longer.” Certain recipes, where the congealing of albumen in an egg where you apply heat, you know, that takes the number of minutes that it takes. Everything takes longer than they say it’s going to take. It’s going to take years. To pay your dues. To get out of a job. Whatever. So it’s that source of tension. Which is that nobody wants to wait that long. Nobody wants to put in the time. And everybody hopes to be ushered past the velvet ropes or somehow upgraded on the great flight. To business class without having deserved it in any way. That’s a constant tension. Not just among me, but I think among every person alive. And every child wants to be suddenly older.

I suppose both essays are an attempt to both make sense of that and also to — if they are speaking to those younger people, to say, “It will be okay. This period shall pass.” And you will look back upon it not fondly. Because that would just be a little nostalgic and kind of unrealistic. But at least with some kind of peace. And I no longer quite begrudge myself those feelings, embarrassing though they may have been — you know.

Correspondent: But not wanting to look back. I’m wondering if this is one of the reasons why your sentences — and even more so with this book — are so ornate and modifier heavy and very phrase happy.

Rakoff: I am phrase happy. That’s a lovely expression! I’ve never heard of it.

Correspondent: Well, it’s one that just occurred to me.

Rakoff: It’s so good.

Correspondent: But if this almost serves as a kind of insulating mechanism, so that if you are going back to your self, you’re doing so in such an idiosyncratic way as to not direct kind of…

Rakoff: Oh, that’s interesting!

Correspondent: Putting your nib into your vein and letting the blood flood onto the page, which is what’s often said about writing.

Rakoff: Yes, it’s true. I guess though that being phrase happy is just inevitable. It’s the way that one moves through the world. You know, it’s the way that one looks at things. It’s the way that one speaks about things. Or rather the way I speak about things. You know, conversation and talking is my favorite thing. It’s my meat. So “phrase happy” is inevitable. It’s interesting to me that you would maybe see it as a kind of mediating or obfuscating screen. Because I see it as the opposite. As a way of actually getting at the exact nature of something. Because a reluctance to look back is not the same thing as not looking back. One cannot help but look back. But you know, it’s inevitable. And it’s not really in my control. So insomuch as I’ve chosen to in certain places, the best I can hope to do is to do so in an accurate and evocative manner. So that someone that I’ve taken along with me (i.e., the reader) will feel like, “Oh, I get what you mean.” That seems very vivid to me and I completely understand what kind of house this was, what kind of experience this was, or something. But, no, I don’t think of the barrage. You know, that huge wave of verbal diarrhea — which is the way I both speak and write –as being a mediating factor. I think of them as being closer to the nib in the vein.

Correspondent: Well, I think maybe it could be both. Words can both insulate and also be the telltale indicator to the reader, “Hey, if you want to go down my journey with me, you’re going to have to wend through my conscious patterns.” You know?

Rakoff: Sure.

Correspondent: And I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing. It’s just the way that you are introspective on the page perhaps.

Rakoff: Precisely. And in life. I’m not one of those minimal guy speakers or writers.

Correspondent: Yeah.

Rakoff: I like words. It’s just like having a lot of spices in my kitchen. It’s just that I like having access to all that stuff.

Correspondent: Well, this also leads me to wonder — because you did bring up words in “A Capacity for Wonder.” You report your concern for bad neologisms. Particularly those that are muffed on lexical blending. Words like “innovention.”

Rakoff: Oh yeah.

Correspondent: Or “snackitizer.”

Rakoff: (laughs)

Correspondent:Or “appeteaser.” In your words, “It makes one suspicious, wondering about the ways in which the object in question is found so wanting, so insufficiently innovative or lacking in invention to warrant this linguistic boost.” I’m wondering. Do you greet all words — all language — with some level of skepticism or suspicion? What does it take for you to trust a word?

Rakoff: Oh! What does it take for me to trust a word? First of all, I have to know what it means.

Correspondent: (laughs)

Rakoff: And there are a lot of words — that as often as I pack my ear with them and look them up all the time — I can’t get them. I’ve even said this in an interview. There was one word. “Vitiate.”

Correspondent: It was our interview! We talked about “vitiate” last time!

Rakoff: Yes! And then I even — I’ve still not gotten “vitiate” — and I’ve said it again in another interview with somebody else!

Correspondent: Yes!

Rakoff: Because I still can’t get it into my head.

Correspondent: To wither or to dry.

Rakoff: It means to either strengthen or weaken an argument. Which one does it mean?

Rakoff: It means to either strengthen or weaken an argument. Which one does it mean?

Correspondent: No. I thought “vitiate” means to —

Rakoff: Strengthen?

Correspondent: To dry. Like…

Rakoff: No.

Correspondent: No, no, no! Because you’re vitiated! Your energy forces are…

Rakoff: No, it means to either strengthen an argument or weaken an argument. One vitiates one’s argument.

Correspondent: Oh, in rhetoric, that is.

Rakoff: I don’t know. In the dictionary. Should I look it up?

Correspondent: We may as well. Because….

Rakoff: All my stuff is in storage.

Correspondent: Wait, I could do it.

Rakoff: (moves off microphone to computer) Wait, I can do it right here. On the Internet.

Correspondent: I was going to suggest. I’ve got a netbook on me too.

Rakoff: Generally, I use a — is this picking up on the tape, you think?

Correspondent: We could — yeah, I think it’s going to pick up. I can boost it or something like this. We’ll get this moment or I’ll — I thought it was “to wither.”

Rakoff: (still faint, on computer) No, I don’t think so. Vitiate.

(Phone rings.)

Correspondent: Yeah. To impair the quality. To make faulty. Spoil. To repair or weaken.

Rakoff: Revert.

Correspondent: Yeah, yeah, yeah!

Rakoff: Interesting.

Correspondent: Well, do you want to answer? (indicates phone) Because I can stop.

Rakoff: No, no, no. I’ll let the machine pick up.

(Rakoff returns to mike.)

Correspondent: Anyway, now that we have used the Internet to confirm what this word is.

Rakoff: Yeah.

Correspondent: Both of us are coming at it slightly wrong. I drew my attention to the weakening aspect of the word and you drew your attention to the rhetorical quality of the word.

Rakoff: Yeah. To ruin one’s argument.

Correspondent: Yes.

Rakoff: So it’s the same.

Correspondent: We had the same idea. We’re close. But both of us are imprecise. I don’t know what that says about us or the word.

Rakoff: I think we are close. I think we both get the word. But it’s funny that we — Jesus, even five years later.

(Image: Kris Krug)

The Bat Segundo Show #362: David Rakoff II (Download MP3)

This text will be replaced

Rakoff: It means to either strengthen or weaken an argument. Which one does it mean?

Rakoff: It means to either strengthen or weaken an argument. Which one does it mean?

Correspondent:

Correspondent:

Mitchell: I think of words as vehicles that convey what is in my imagination into someone else’s. And we’re sort of in a dialogue. Because they don’t just replicate what’s in the imagination. They can alter it. You can mistype and you get a word that actually can be better than the one you meant. Words can feed back and suggest to the imagination, “Well, would it be neater if you imagine this instead?” Language itself is a kind of a writing partner, separate to the writer, who is deploying the language. I think. I think this is true. Has that answered your question?

Mitchell: I think of words as vehicles that convey what is in my imagination into someone else’s. And we’re sort of in a dialogue. Because they don’t just replicate what’s in the imagination. They can alter it. You can mistype and you get a word that actually can be better than the one you meant. Words can feed back and suggest to the imagination, “Well, would it be neater if you imagine this instead?” Language itself is a kind of a writing partner, separate to the writer, who is deploying the language. I think. I think this is true. Has that answered your question?

Correspodnent: Does movement offer a more creative place to establish a character? More so than the backstory, research, or anything?

Correspodnent: Does movement offer a more creative place to establish a character? More so than the backstory, research, or anything? Correspondent: You note of [your future husband] Ben that, as you watched him calmly rub soap into his hands by the communal sink, you realized that you had known all along that you would see him again. I’m wondering what it is about hand hygiene that serves as your personal madeleine.

Correspondent: You note of [your future husband] Ben that, as you watched him calmly rub soap into his hands by the communal sink, you realized that you had known all along that you would see him again. I’m wondering what it is about hand hygiene that serves as your personal madeleine.

Ross: I think that what keeps us going day in and day out as we live our lives — and certainly we live our lives, hopefully, as members of caring relationships — is the belief that we can improve and change. And when I think of the idea of change, progress, and the improvability of character, that to me is a belief that character is somewhat linear. Right? That, okay, I learned that lesson back then. I’m never going to do it again. And yet my experience as a guy who’s been successfully married for fifteen years is that the experience of living with someone you care about a great deal for a long period of time is to come up against the reef of circularity, but also to enjoy the bliss of recurrence, right? So it’s paradoxical. There are these competing desires. The closed circles that Mr. Peanut presents. The entrapment, which is the same experience, I think, of looking at Escher. Which is that weird — you look at the art object from the outside. But if you really enter an Escher, you have this perceptual experience, where it’s inescapable and then you have to step back. It’s to me kind of analogous to the experience we often feel with those closest to us. Whether it’s brothers/sisters, mothers/fathers, or husbands/wives, we want to believe that we could get past X. But we often don’t. And that, to me, is the heaven and hell of marriage.

Ross: I think that what keeps us going day in and day out as we live our lives — and certainly we live our lives, hopefully, as members of caring relationships — is the belief that we can improve and change. And when I think of the idea of change, progress, and the improvability of character, that to me is a belief that character is somewhat linear. Right? That, okay, I learned that lesson back then. I’m never going to do it again. And yet my experience as a guy who’s been successfully married for fifteen years is that the experience of living with someone you care about a great deal for a long period of time is to come up against the reef of circularity, but also to enjoy the bliss of recurrence, right? So it’s paradoxical. There are these competing desires. The closed circles that Mr. Peanut presents. The entrapment, which is the same experience, I think, of looking at Escher. Which is that weird — you look at the art object from the outside. But if you really enter an Escher, you have this perceptual experience, where it’s inescapable and then you have to step back. It’s to me kind of analogous to the experience we often feel with those closest to us. Whether it’s brothers/sisters, mothers/fathers, or husbands/wives, we want to believe that we could get past X. But we often don’t. And that, to me, is the heaven and hell of marriage.