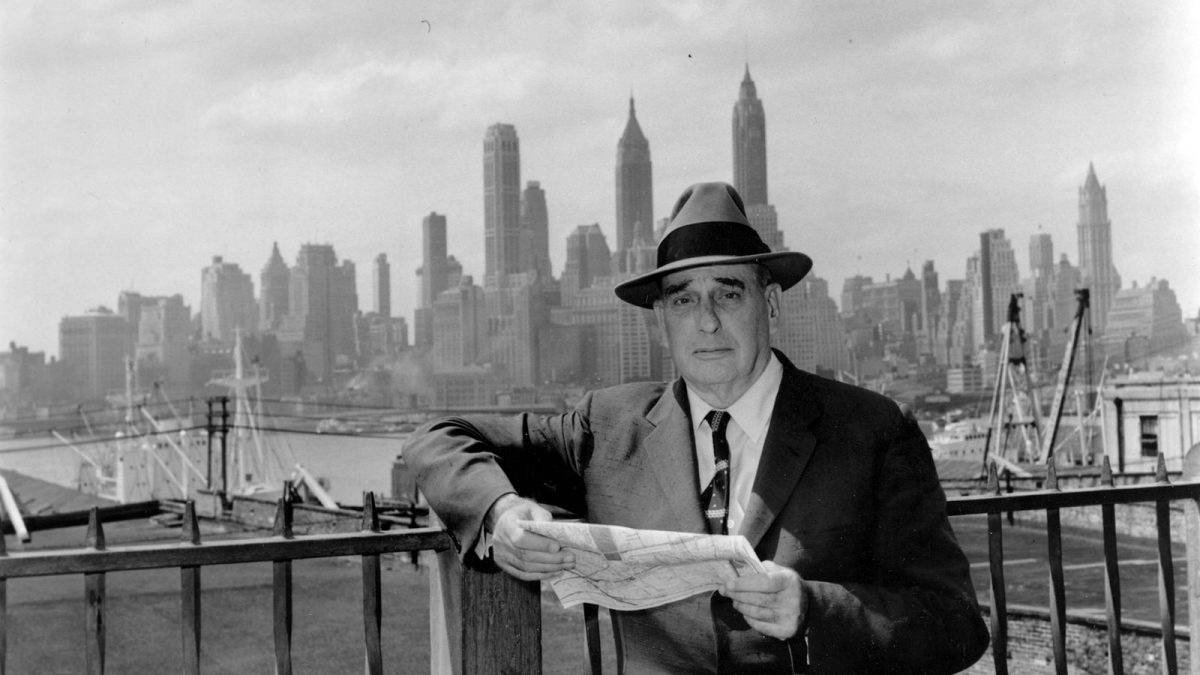

(This is the twelfth entry in The Modern Library Nonfiction Challenge, an ambitious project to read and write about the Modern Library Nonfiction books from #100 to #1. There is also The Modern Library Reading Challenge, a fiction-based counterpart to this list. Previous entry: The Golden Bough.)

“Either this world, my mother, is a monster, or I myself am a freak.” — Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

I was a sliver-thin, stupefyingly shy, and very excitable boy who disguised his bruises under the long sleeves of his shirt not long before the age of five. I was also a freak.

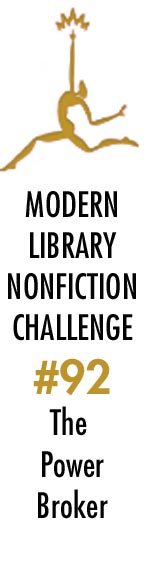

I had two maps pinned to the wall of my drafty bedroom, which had been hastily constructed into the east edge of the garage in a house painted pink (now turquoise, according to Google Maps). The first map was of Tolkien’s Middle-earth, in which I followed the quests of Bilbo and Frodo by finger as I wrapped my precocious, word-happy head around sentences that I’d secretly study from the trilogy I had purloined from the living room, a well-thumbed set that I was careful to put back to the shelves before my volatile and often sour father returned home from the chemical plant. In some of his rare calm moments, my father read aloud from The Lord of the Rings if he wasn’t too drunk, irascible, or violent. His voice led me to imagine Shelob’s thick spidery thistles, Smeagol’s slithering corpus, and kink open my eyes the next morning for any other surprises I might divine in my daily journeys to school. The second map was of Santa Clara County, a very real region that everyone now knows as Silicon Valley but that used to be a sweeping swath of working and lower middle-class domiciles. This was one of several dozen free maps of Northern California that I had procured from AAA with my mother’s help. One of the nice perks of being an AAA member was the ample sample of rectangular geographical foldouts. I swiftly memorized all of the streets, held spellbound by the floral and butterfly patterns of freeway intersections seen from a majestic bird’s eye view in an errant illustrated sky. My mother became easily lost while driving and I knew the avenues and the freeways in more than a dozen counties so well that I could always provide an easy cure for her confusion. It is a wonder that I never ended up working as a cab driver, although my spatial acumen has remained so keen over the years that, to this day, I can still pinpoint the precise angle in which you need to slide a thick unruly couch into the tricky recesses of a small Euclidean-angled apartment even when I am completely exhausted.

I had two maps pinned to the wall of my drafty bedroom, which had been hastily constructed into the east edge of the garage in a house painted pink (now turquoise, according to Google Maps). The first map was of Tolkien’s Middle-earth, in which I followed the quests of Bilbo and Frodo by finger as I wrapped my precocious, word-happy head around sentences that I’d secretly study from the trilogy I had purloined from the living room, a well-thumbed set that I was careful to put back to the shelves before my volatile and often sour father returned home from the chemical plant. In some of his rare calm moments, my father read aloud from The Lord of the Rings if he wasn’t too drunk, irascible, or violent. His voice led me to imagine Shelob’s thick spidery thistles, Smeagol’s slithering corpus, and kink open my eyes the next morning for any other surprises I might divine in my daily journeys to school. The second map was of Santa Clara County, a very real region that everyone now knows as Silicon Valley but that used to be a sweeping swath of working and lower middle-class domiciles. This was one of several dozen free maps of Northern California that I had procured from AAA with my mother’s help. One of the nice perks of being an AAA member was the ample sample of rectangular geographical foldouts. I swiftly memorized all of the streets, held spellbound by the floral and butterfly patterns of freeway intersections seen from a majestic bird’s eye view in an errant illustrated sky. My mother became easily lost while driving and I knew the avenues and the freeways in more than a dozen counties so well that I could always provide an easy cure for her confusion. It is a wonder that I never ended up working as a cab driver, although my spatial acumen has remained so keen over the years that, to this day, I can still pinpoint the precise angle in which you need to slide a thick unruly couch into the tricky recesses of a small Euclidean-angled apartment even when I am completely exhausted.

These two maps seemed to be the apotheosis of cartographic art at the time, filling me with joy and wonder and possibility. It helped me cope with the many problems I lived with at home. I understood that there were other regions beyond my bedroom where I could wander in peace, where I could meet kinder people or take in the beatific comforts of a soothing lake (Vasona Lake, just west of Highway 17 in Los Gatos, had a little railroad spiraling around its southern tip and was my real-life counterpart to Lake Evendim), where the draw of Rivendell’s elvish population or the thrill of smoky Smaug stewing inside the Lonely Mountain collided against visions of imagined mountain dwellers I might meet somewhere within the greens and browns of Santa Teresa Hills and the majestic observatories staring brazenly into the cosmos at the end of uphill winding roads. I would soon start exploring the world I had espied from my improvised bedroom study on my bike, pedaling unfathomable miles into vicinities I had only dreamed about, always seeking parallels to what the Oxford professor had whipped up. I once ventured as far south as Gilroy down the Monterey Highway, which Google Maps now informs me is a thirty-six mile round trip, because my neglectful parents never kept tabs on how long I was out of the house or where I was going. They didn’t seem to care. As shameful as this was, I’m glad they didn’t. I needed an uncanny dominion, a territory to flesh out, in order to stay happy, humble, and alive.

These two maps seemed to be the apotheosis of cartographic art at the time, filling me with joy and wonder and possibility. It helped me cope with the many problems I lived with at home. I understood that there were other regions beyond my bedroom where I could wander in peace, where I could meet kinder people or take in the beatific comforts of a soothing lake (Vasona Lake, just west of Highway 17 in Los Gatos, had a little railroad spiraling around its southern tip and was my real-life counterpart to Lake Evendim), where the draw of Rivendell’s elvish population or the thrill of smoky Smaug stewing inside the Lonely Mountain collided against visions of imagined mountain dwellers I might meet somewhere within the greens and browns of Santa Teresa Hills and the majestic observatories staring brazenly into the cosmos at the end of uphill winding roads. I would soon start exploring the world I had espied from my improvised bedroom study on my bike, pedaling unfathomable miles into vicinities I had only dreamed about, always seeking parallels to what the Oxford professor had whipped up. I once ventured as far south as Gilroy down the Monterey Highway, which Google Maps now informs me is a thirty-six mile round trip, because my neglectful parents never kept tabs on how long I was out of the house or where I was going. They didn’t seem to care. As shameful as this was, I’m glad they didn’t. I needed an uncanny dominion, a territory to flesh out, in order to stay happy, humble, and alive.

The maps opened up my always hungry eyes to books, which contained equally bountiful spaces devoted to the real and the imaginary, unspooling further marks and points for me to find in the palpable world and, most importantly, within my heart. I always held onto this strange reverence for place to beat back the sadness after serving as my father’s punching bag. To this day, I remain an outlier, a nomad, a lifelong exile, a wanderer even as I sit still, a renegade hated for what people think I am, a black sheep who will never belong no matter how kind I am. I won’t make the mistake of painting myself as some virtuous paragon, but I’ve become so accustomed to being condemned on illusory cause, to having all-too-common cruelties inflicted upon me (such as the starry-eyed bourgie Burning Man sybarite I recently opened my heart to, who proceeded to deride the city that I love, along with the perceived deficiencies of my hard-won apartment, this after I had told her tales, not easily summoned, about what it was like to be rootless and without family and how home and togetherness remain sensitive subjects for me) that the limitless marvels of the universe parked in my back pocket or swiftly summoned from my shelves or my constant peregrinations remain reliable, life-affirming balms that help heal the scars and render the wounds invisible. Heartbreak and its accompanying gang of thugs often feel like a mob bashing in your ventricles in a devastatingly distinct way, even though the great cosmic joke is that everyone experiences it and we have to love anyway.

So when Annie Dillard’s poetic masterpiece Pilgrim at Tinker Creek entered my reading life, its ebullient commitment to finding grace and gratitude in a monstrous world reminded me that seeing and perceiving and delving and gaping awestruck at Mother Earth’s endless glories seemed to me one one of the best survival skills you can cultivate and that I may have accidentally stumbled upon. As I said, I’m a freak. But Dillard is one too. And there’s a good chance you may walk away from this book, which I highly urge you to read, feeling a comparable kinship, as I did to Dillard. Even if you already have a formidable arsenal of boundless curiosity ready to be summoned at a moment’s notice, this shining 1974 volume remains vital and indispensable and will stir your soul for the better, whether you’re happy or sad. Near the end of a disastrous year, we need these inspirational moments now more than ever.

“Our life is a faint tracing on the surface of mystery.” – Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

Annie Dillard was only 28 when she wrote this stunning 20th century answer to Thoreau (the subject of her master’s thesis), which is both a perspicacious journal of journeying through the immediately accessible wild near her bucolic Southwestern Virginia perch and a daringly honest entreaty for consciousness and connection. Dillard’s worldview is so winningly inclusive that she can find wonder in such savage tableaux as a headless praying mantis clutching onto its mate or the larval creatures contained within a rock barnacle. The Washington Post claimed not long after Pilgrim‘s publication that the book was “selling so well on the West Coast and hipsters figure Annie Dillard’s some kind of female Castaneda, sitting up on Dead Man’s Mountain smoking mandrake roots and looking for Holes in the Horizon her guru said were there.” But Pilgrim, inspired in part from Colette’s Break of Day, is far from New Age nonsense. The book’s wise and erudite celebration of nature and spirituality was open and inspiring enough to charm even this urban-based secular humanist, who desperately needed a pick-me-up and a mandate to rejoin the world after a rapid-fire series of personal and political and romantic and artistic setbacks that occurred during the last two weeks.

For all of the book’s concerns with divinity, or what Dillard identifies as “a divine power that exists in a particular place, or that travels about over the face of the earth as a man might wander,” explicit gods don’t enter this meditation until a little under halfway through the book, where she points out jokingly how gods are often found on mountaintops and points out that God is an igniter as well as a destroyer, one that seeks invisibility for cover. And as someone who does not believe in a god and who would rather deposit his faith in imaginative storytelling and myth rather than the superstitions of religious ritual, I could nevertheless feel and accept the spiritual idea of being emotionally vulnerable while traversing into some majestic terrain. Or as Pascal wrote in Pensées 584 (quoted in part by Dillard), “God being thus hidden, every religion which does not affirm that God is hidden, is not true, and every religion which does not give the reason of it, is not instructive.”

Much of this awe comes through the humility of perceiving, of devoting yourself to sussing out every conceivable kernel that might present itself and uplift you on any given day and using this as the basis to push beyond the blinkered cage of your own self-consciousness. Dillard uses a metaphor of loose change throughout Pilgrim that neatly encapsulates this sentiment:

It is dire poverty indeed when a man is so malnourished and fatigued that he won’t stoop to pick up a penny. But if you cultivate a healthy poverty and simplicity, so that finding a penny will literally make your day, then, since the world is in fact planted in pennies, you have with your poverty bought a lifetime of days. It is that simple. What you see is what you get.

This is not too far removed from Thoreau’s faith in seeds: “Convince me that you have a seed there, and I am prepared to expect wonders.” The smug and insufferable Kathryn Schulzes of our world gleefully misread this great tradition of discovering possibilities in the small as arrogance, little realizing how their own blind and unimaginative hubris glows with crass Conde Nast entitlement as they fail to observe that Thoreau and Dillard were also acknowledging the ineluctable force of a bigger and fiercer world that will carry on with formidable complexity long after our dead bodies push against daisies. Faced with the choice of sustaining a sour Schulz-like apostasy or receiving every living day as a gift, I’d rather risk the arrogance of dreaming from the collected riches of what I have and what I can give rather than the gutless timidity of a prescriptive rigidity that fails to consider that we are all steeped in foolish and inconsistent behavior which, in the grand scheme of things, is ultimately insignificant.

Dillard is guided just as much by Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle as she is by religious and philosophical texts. The famous 1927 scientific law, which articulates how you can never know a particle’s speed and velocity at the same time, is very much comparable to chasing down some hidden deity or contending with some experiential palpitations when you understand that there simply is no answer, for one can feel but never fully comprehend the totality in a skirmish with Nature. It accounts for Dillard frequently noting that the towhee chirping on a treetop or the muskrat she observes chewing grass on a bank for forty minutes never see her. In seeing these amazing creatures carry on with their lives, who are completely oblivious to her own human vagaries, Dillard reminds us that this is very much the state of Nature, whether human or animal. If it is indeed arrogance to find awe and humility in this state of affairs, as Dillard and Thoreau clearly both did, then one’s every breath may as well be a Napoleonic puff of the chest.

Dillard is also smart and expansive enough to show us that, no matter where we reside, we are fated to brush up against the feral. She points to how arboreal enthusiasts in the Lower Bronx discovered a fifteen feet ailanthus tree growing from a lower Bronx garage and how New York must spend countless dollars each year to rid its underground water pipes of roots. Such realities are often contended with out of sight and out of mind, even as the New York apartment dweller battles cockroaches, but the reminder is another useful point for why we must always find the pennies and dare to dream and wander and take in, no matter what part of the nation we dwell in.

Another refreshing aspect of Pilgrim is the way in which Dillard confronts her own horrors with fecundity. Yes, even this graceful ruminator has the decency to confess her hangups about the unsettling rapidity with which moths lay their eggs in vast droves. She stops short at truly confronting “the pressure of birth and growth” that appalls her, shifting to plants as a way of evading animals and then retreating back to the blood-pumping phylum to take in blood flukes and aphid reproduction more as panorama rather than something to be felt. This volte-face isn’t entirely satisfying. On the other hand, Dillard is also bold enough to scoop up a cup of duck-pond water and peer at monostyla under a microscope. What this tells us is that there are clear limits to how far any of us are willing to delve, yet I cannot find it within me to chide Dillard too harshly for a journey she was not quite willing to take, for this is an honest and heartfelt chronicle.

While I’ve probably been “arrogant” in retreating at length to my past in an effort to articulate how Dillard’s book so moved me, I would say that Pilgrim at Tinker Creek represents a third map for my adult years. It is a true work of art that I am happy to pin to the walls of my mind, which seems more reliable than any childhood bedroom. This book has caused me to wonder why I have ignored so much and has demanded that that I open myself up to any penny I could potentially cherish and to ponder what undiscoverable terrain I might deign to take in as I continue to walk this earth. I do not believe in a god, but I do feel with all my heart that one compelling reason to live is to fearlessly approach all that remains hidden. There is no way that you’ll ever know or find everything, but Dillard’s magnificent volume certainly gives you many good reasons to try.

Next Up: Richard Feynman’s Six Easy Pieces!

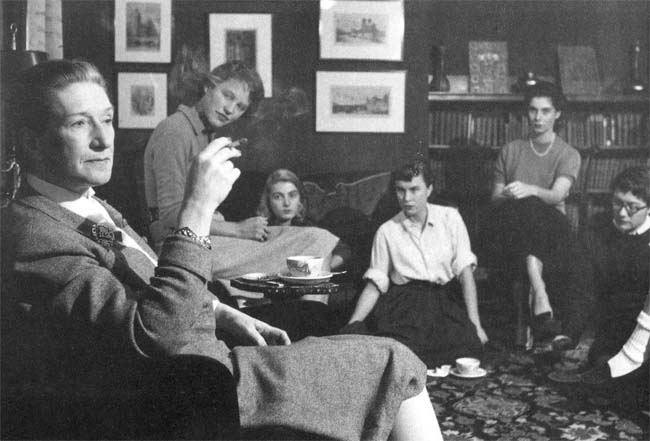

It is easy to forget, as brave women

It is easy to forget, as brave women

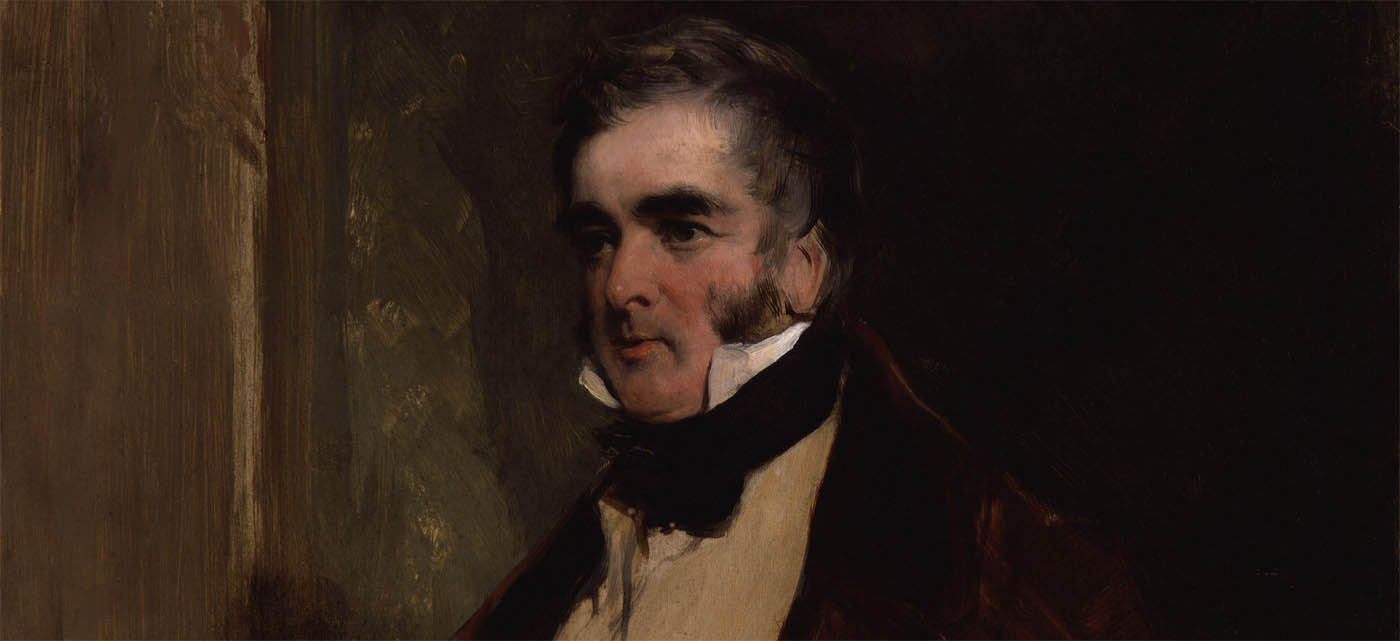

History has produced such a rich pile of devious political figures who spend every spare minute scheming and plotting their rise that today’s aspiring aristocrats, who can be found working every connection to get their kids into bright educational citadels and reliable sinecures, cannot come close to such cutthroat monomania. Yet there are also those who blunder into top office like bumpkins crashing high-class weddings through the simple repetitive act of placing one foot in front the other. William Lamb, aka Lord Melbourne, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom for eight years (1834, 1835-1841) and the subject of Lord David Cecil’s generous biography, was one such man.

History has produced such a rich pile of devious political figures who spend every spare minute scheming and plotting their rise that today’s aspiring aristocrats, who can be found working every connection to get their kids into bright educational citadels and reliable sinecures, cannot come close to such cutthroat monomania. Yet there are also those who blunder into top office like bumpkins crashing high-class weddings through the simple repetitive act of placing one foot in front the other. William Lamb, aka Lord Melbourne, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom for eight years (1834, 1835-1841) and the subject of Lord David Cecil’s generous biography, was one such man.

Three years ago, my jocular compadre Lydia Kiesling

Three years ago, my jocular compadre Lydia Kiesling

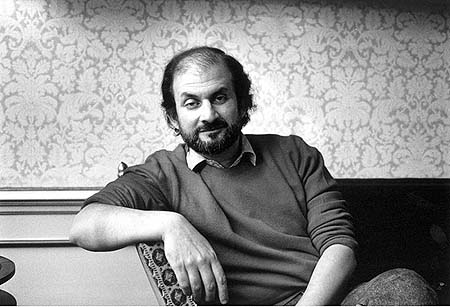

Merchant Ivory Productions has been one of the greatest threats to literature during the past three decades. Known for producing well photographed films that put most sane people to sleep, the Merchant Ivory team has demonstrated a remarkable knack for divesting zest from the literary classics. They have ordered esteemed actors across sweeping vistas as if they are unbudgeable bovine who require vast encouragement to produce milk. They have bored more often than seems reasonable. Where Orson Welles’s Shakespeare adaptations or Iain Softley’s The Wings of the Dove or Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon or Sally Potter’s Orlando or William Wyler’s The Heiress or Corman’s Poe pictures or The Royal Shakespeare Company’s nine hour version of Nicholas Nickleby bristle with life and visual excitement, demanding that you get your hands on the source material at once, the Merchant Ivory movies are the cinematic equivalent to visiting the in-laws or steeling yourself up for a dreadful Thanksgiving or attending a funeral for someone you didn’t really know that well.

Merchant Ivory Productions has been one of the greatest threats to literature during the past three decades. Known for producing well photographed films that put most sane people to sleep, the Merchant Ivory team has demonstrated a remarkable knack for divesting zest from the literary classics. They have ordered esteemed actors across sweeping vistas as if they are unbudgeable bovine who require vast encouragement to produce milk. They have bored more often than seems reasonable. Where Orson Welles’s Shakespeare adaptations or Iain Softley’s The Wings of the Dove or Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon or Sally Potter’s Orlando or William Wyler’s The Heiress or Corman’s Poe pictures or The Royal Shakespeare Company’s nine hour version of Nicholas Nickleby bristle with life and visual excitement, demanding that you get your hands on the source material at once, the Merchant Ivory movies are the cinematic equivalent to visiting the in-laws or steeling yourself up for a dreadful Thanksgiving or attending a funeral for someone you didn’t really know that well.

Soak up enough art over the years and you’ll run into the cultural dichotomy, either through half-cocked introspection or cocktail party gunpoint. It’s a practice where two artists of equal merit and/or influence are positioned at opposing ends in talk, much as an oily advertising tyrant pins blindfolds on fat suburban heads to establish the next tasteless drink to slam down lacquered American throats.

Soak up enough art over the years and you’ll run into the cultural dichotomy, either through half-cocked introspection or cocktail party gunpoint. It’s a practice where two artists of equal merit and/or influence are positioned at opposing ends in talk, much as an oily advertising tyrant pins blindfolds on fat suburban heads to establish the next tasteless drink to slam down lacquered American throats.

For more than a decade, I have nursed a grandiose grudge towards Wallace Stegner that has less to do with the eco-friendly West Coast bigshot’s literary streetcred and more to do with my own irrepressible ineptitude concerning matters of the boudoir.

For more than a decade, I have nursed a grandiose grudge towards Wallace Stegner that has less to do with the eco-friendly West Coast bigshot’s literary streetcred and more to do with my own irrepressible ineptitude concerning matters of the boudoir.

There are so many unpardonable cruelties collected in Patrick French’s gripping (and authorized!) biography, The World Is What It Is, that it’s difficult to know where to start in condemning V.S. Naipaul’s boorish behavior, while also praising his prowess on the page. And yet I can’t quite do that either. I’ve read A Bend in the River twice, and I have to conclude that the book’s pat pronouncements about colonialism, even with the adept take on self-deception and willful naïveté, aren’t especially staggering. By the time the shopkeeper Salim shows his colleague Indar around the African town where he lives and reveals how little he knows (“All the key points of the town I knew could be shown in a couple of hours, as I discovered when I drove him around later that morning”), it was abundantly clear to me that he would never know.

There are so many unpardonable cruelties collected in Patrick French’s gripping (and authorized!) biography, The World Is What It Is, that it’s difficult to know where to start in condemning V.S. Naipaul’s boorish behavior, while also praising his prowess on the page. And yet I can’t quite do that either. I’ve read A Bend in the River twice, and I have to conclude that the book’s pat pronouncements about colonialism, even with the adept take on self-deception and willful naïveté, aren’t especially staggering. By the time the shopkeeper Salim shows his colleague Indar around the African town where he lives and reveals how little he knows (“All the key points of the town I knew could be shown in a couple of hours, as I discovered when I drove him around later that morning”), it was abundantly clear to me that he would never know.

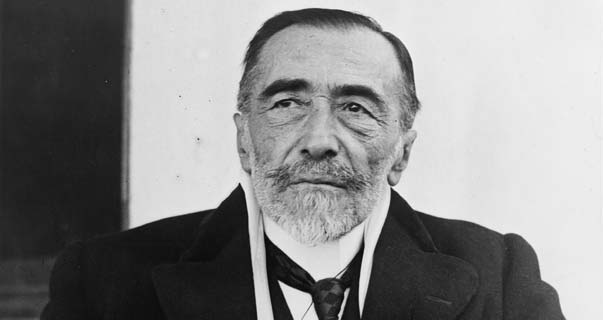

Much like today’s tawdry Hollywood movies, Lord Jim was based on a true story — back in the days when it actually meant something. On August 7, 1880, a ship called the Jeddah, on its way from Singapore to Arabia and carrying 950 Muslim pilgrims, had an accident. The British officers abandoned the ship near Cape Gardafui. But the Jeddah did not sink. Captain Clark was on his way out of the British Consulate when another captain reported that the Jeddah had been salvaged and towed. Clark got off lightly. His certificate was stripped for three years. But the Jeddah‘s first mate, Augustine Podmore Williams, received a harsher sentence.

Much like today’s tawdry Hollywood movies, Lord Jim was based on a true story — back in the days when it actually meant something. On August 7, 1880, a ship called the Jeddah, on its way from Singapore to Arabia and carrying 950 Muslim pilgrims, had an accident. The British officers abandoned the ship near Cape Gardafui. But the Jeddah did not sink. Captain Clark was on his way out of the British Consulate when another captain reported that the Jeddah had been salvaged and towed. Clark got off lightly. His certificate was stripped for three years. But the Jeddah‘s first mate, Augustine Podmore Williams, received a harsher sentence.

In 1975,

In 1975,

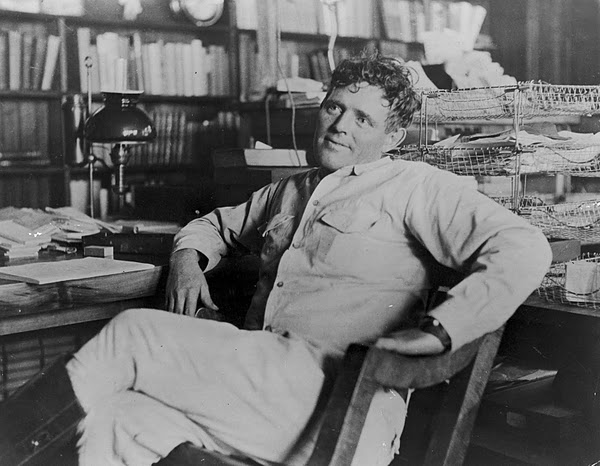

I am fairly certain that I found The Old Wives’ Tale compelling for reasons that Arnold Bennett did not intend. After my great excitement with Jack London, Bennett was something of a letdown, reading more like fossilized culch than a lively adventure from the 20th century, although I experienced a great deal of pleasure as characters began to die and as they became needlessly blamed for other deaths. Consider the manner in which Sophia, assigned to watch over her bedridden father, sneaks away for a few minutes to chat with the strapping Gerald Scales. When she returns, something terribly odd occurs:

I am fairly certain that I found The Old Wives’ Tale compelling for reasons that Arnold Bennett did not intend. After my great excitement with Jack London, Bennett was something of a letdown, reading more like fossilized culch than a lively adventure from the 20th century, although I experienced a great deal of pleasure as characters began to die and as they became needlessly blamed for other deaths. Consider the manner in which Sophia, assigned to watch over her bedridden father, sneaks away for a few minutes to chat with the strapping Gerald Scales. When she returns, something terribly odd occurs:

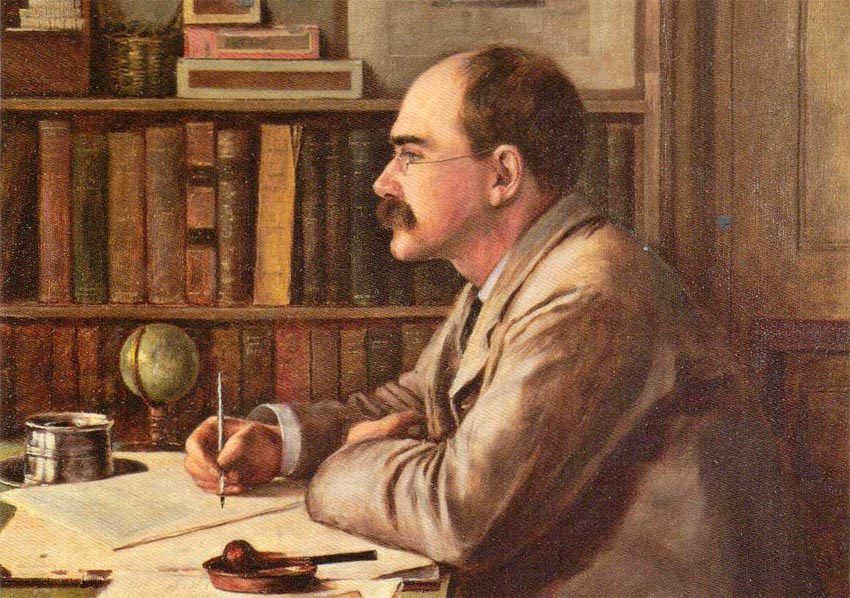

In June 1902, Cosmopolitan published

In June 1902, Cosmopolitan published

Reading Henry Green’s Loving is a bit like going through a valise that a hardcore neat freak has spent many years packing for your once-in-a-decade vacation. You need to extract the chinos for that last summer blowout, but will your unseen friend berate you if you rustle the crisp blue oxford shirt from that fixed and implacable perch just above those promising pants? What Green has given us is a delicate book, difficult to unpack in a thousand words. It is so marvelous that you could spend a lifetime talking about it (certainly many have spent lifetimes teaching it). On the other hand, compared to Finnegans Wake (a Modern Library obligation so massive that I have started reading it early,

Reading Henry Green’s Loving is a bit like going through a valise that a hardcore neat freak has spent many years packing for your once-in-a-decade vacation. You need to extract the chinos for that last summer blowout, but will your unseen friend berate you if you rustle the crisp blue oxford shirt from that fixed and implacable perch just above those promising pants? What Green has given us is a delicate book, difficult to unpack in a thousand words. It is so marvelous that you could spend a lifetime talking about it (certainly many have spent lifetimes teaching it). On the other hand, compared to Finnegans Wake (a Modern Library obligation so massive that I have started reading it early,

Like many great writers of the 20th century, Erskine Caldwell experienced difficulties keeping his dick in his pants. While such bulging foibles aren’t normally the stuff of pertinent consideration, Erskine Caldwell Reconsidered (edited by Edwin T. Arnold and published by the University Press of Mississippi) is the rare academic volume offering a partially persuasive case that Caldwell’s philandering was one throbbing element of the creative package.

Like many great writers of the 20th century, Erskine Caldwell experienced difficulties keeping his dick in his pants. While such bulging foibles aren’t normally the stuff of pertinent consideration, Erskine Caldwell Reconsidered (edited by Edwin T. Arnold and published by the University Press of Mississippi) is the rare academic volume offering a partially persuasive case that Caldwell’s philandering was one throbbing element of the creative package.

William Kennedy was in his mid-fifties when all of his novels went out of print. While he remained a working journalist, his latest manuscript about a scuffed up drifter named Francis Phelan — a minor character from his 1978 novel, Billy Phelan’s Greatest Game — had been rejected by thirteen publishers. Ironweed had come comparatively quicker than his previous novels. Kennedy wrote eight versions of Legs over six years. He devoted two years to Billy Phelan. But he wrote Ironweed in seven months. Still, this unanticipated celerity was of null solace to publishers studying Kennedy’s then sketchy sales record.

William Kennedy was in his mid-fifties when all of his novels went out of print. While he remained a working journalist, his latest manuscript about a scuffed up drifter named Francis Phelan — a minor character from his 1978 novel, Billy Phelan’s Greatest Game — had been rejected by thirteen publishers. Ironweed had come comparatively quicker than his previous novels. Kennedy wrote eight versions of Legs over six years. He devoted two years to Billy Phelan. But he wrote Ironweed in seven months. Still, this unanticipated celerity was of null solace to publishers studying Kennedy’s then sketchy sales record.

Over the course of several interviews, John Fowles enjoyed recycling one particular anecdote concerning The Magus. The then bigshot author once received a letter from a woman who didn’t care for his book. The woman asked Fowles if two of the novel’s characters got together at the end. Fowles wrote back and said, “No.” He received another letter from a New York attorney dying of cancer in a hospital. The lawyer asked the same question, but, unlike the woman, informed Fowles that he enjoyed the book. Fowles replied, “Yes.” In 1986, Fowles would tell a dull interviewer seeking literal-minded answers, “I tell that story because that’s how I feel — I don’t know the answer. And I tend to react as people want, or don’t want it — if they’ve annoyed me — to end.” But Fowles’s story after the story does have me wondering about the novelist’s responsibility. If a novelist leaves his volume open-ended, does he not have some duty to know every aspect of his characters as he knows the back of his hand? On the other hand, if Fowles led his narcissistic schoolteacher Nicholas Urfe to a specific point, perhaps he’s off the hook for anything beyond these final words:

Over the course of several interviews, John Fowles enjoyed recycling one particular anecdote concerning The Magus. The then bigshot author once received a letter from a woman who didn’t care for his book. The woman asked Fowles if two of the novel’s characters got together at the end. Fowles wrote back and said, “No.” He received another letter from a New York attorney dying of cancer in a hospital. The lawyer asked the same question, but, unlike the woman, informed Fowles that he enjoyed the book. Fowles replied, “Yes.” In 1986, Fowles would tell a dull interviewer seeking literal-minded answers, “I tell that story because that’s how I feel — I don’t know the answer. And I tend to react as people want, or don’t want it — if they’ve annoyed me — to end.” But Fowles’s story after the story does have me wondering about the novelist’s responsibility. If a novelist leaves his volume open-ended, does he not have some duty to know every aspect of his characters as he knows the back of his hand? On the other hand, if Fowles led his narcissistic schoolteacher Nicholas Urfe to a specific point, perhaps he’s off the hook for anything beyond these final words:

In Geoff Dyer’s Otherwise Known as the Human Condition, there’s an essay in which Dyer describes his reading habits. He writes about a late stage wade into Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea. “I could make neither head nor tail of the first part,” notes Dyer. “[B]ut, since the book was short and the end in sight almost from the first page, I finished it and realized that it was indeed the masterpiece everyone had claimed.” It’s safe to say that this knowingly superficial take, coming from a man

In Geoff Dyer’s Otherwise Known as the Human Condition, there’s an essay in which Dyer describes his reading habits. He writes about a late stage wade into Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea. “I could make neither head nor tail of the first part,” notes Dyer. “[B]ut, since the book was short and the end in sight almost from the first page, I finished it and realized that it was indeed the masterpiece everyone had claimed.” It’s safe to say that this knowingly superficial take, coming from a man