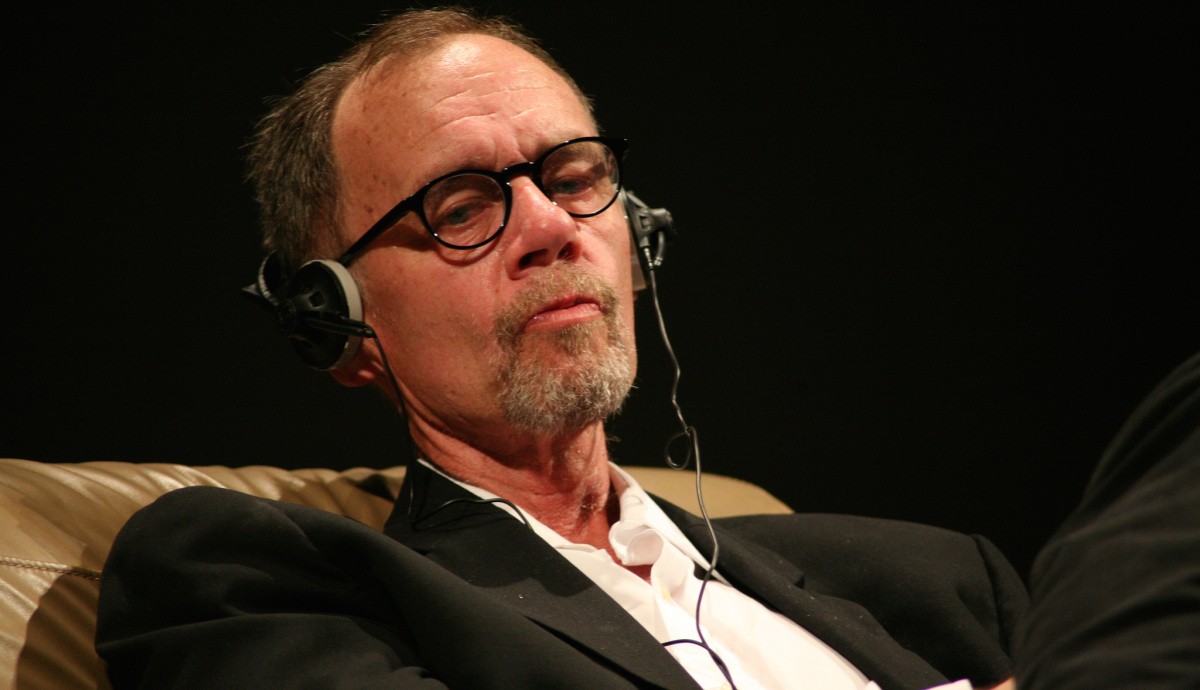

David Lynch has passed away. He was 78 years old. And he was a genius in every sense of the word.

If I had to name the artist who influenced me the most, then the name I would serve up – without a moment of hesitation — is David Lynch.

There was nobody else like David Lynch. Nobody. And there never will be again. He was an ambassador to the weird. A chronicler of the real America, particularly its dark and dreamy underside. He was a champion of outliers, misfits, and outcasts. A brilliant on-set improviser who would see someone interesting — such as stagehand Frank Silva, who played Bob in Twin Peaks and became part of the labyrinthine storyline simply because Lynch liked the way he was looking upwards while crouched — and work him into what he was making at the time. An indefatigable practitioner of the strange who spoke in a reedy high-pitched voice that not even the many cigarettes he smoked could seem to dull. (He employed his thespic talents as the hard-of-hearing and constantly shouting FBI Agent Gordon Cole and, to gut-bustingly comedic effect, for his final short film in 2017 — “What Would Jack Do?” — which featured Lynch with a talking monkey. You can also see him as John Ford in Spielberg’s incredibly underrated film, The Fabelmans. Of course, Lynch steals the movie.)

It is difficult to articulate just how important David Lynch was – not just to film, but to American culture. Because make no mistake: his loss leaves a continent-sized hole that will take hundreds of wild and unapologetically expressive artists to fill. Lynch had so many talents (he painted, he put out music, he wrote an incredibly entertaining memoir Room to Dream, and he even taught himself Macromedia Flash to create DumbLand – a willfully crude set of eight hilariously warped animated shorts), but perhaps his greatest gift was to introduce avant-garde to mainstream audiences and thus inspire shy kids like me to push the expressive envelope as far as we could and seek out many of the same bizarre influences.

In 1990 — an age long before viral videos, smartphones, and broadband Internet — David Lynch grabbed our collective lapels with Twin Peaks, perhaps the most revolutionary television series in American history. He served up sound, images, and characters that had never been seen before on the boob tube. The Log Lady. The Man from Another Place. Sound willingly reversed. The Black Lodge, with its red curtains and its zigzag carpet. All set to a seductive Angelo Badalamenti score that, for a brief time in the early nineties, seemed to be playing in every other cafe.

I think Twin Peaks became the cultural phenomenon that it did because we all had the underlying sense that something audacious and alive had been missing from television. Sure, the normies were scared away near the start of the second season, when it was perfectly clear that the question “Who killed Laura Palmer?” was not the actual reason behind the show. My parents initially loved it and then hated it. Me? I stuck with it the entire time and, as a teenager, I had to go to friends’ houses to see the new episodes, where I recall other kids making out on couches and one of us somehow procuring beer. We would talk about each episode for a long time after it aired, dissecting every strange image and symbol that had improbably been transmitted to a mass audience. I remember vivacious conversations with fellow all-black wearing theatre kids in high school about this brilliant, life-changing show.

What other crazy shit was out there? And why weren’t we allowed to see it? It is a question still germane to this very day as the American government has decided to ban TikTok — a sui generis platform for the wild and the weird — on Sunday. David Lynch somehow had the finesse to skate past the unspoken artistic prohibitions — whether corporate or governmental — and was nimble and charming enough to persuade big studios to finance his films. (The Straight Story, a deeply moving masterpiece of a dying and disabled man traveling by way of a John Deere lawnmower across America, has never failed to reduce me to tears and was, believe it or not, financed by Disney. You can still watch it on Disney’s streaming services. When the MPAA gave the film a G rating, David Lynch replied, “I’m sorry. You’re going to have to say that again. This is probably the only time I’ll ever hear this.”)

David Lynch inspired me not just on the film front, but on the sound front. (To this very day, as I’ve been working very hard on the new scripts for the third season of my audio drama — close to two thousand pages of creative labor so far — “Lynchian” has often been used as shorthand for sound cues.) During the third season of Twin Peaks, Lynch credited himself as sound designer as well as director. His extremely underrated television show, On the Air, was a love letter to old time radio. And so, for that matter, is Part 8 of Twin Peaks: The Return, which is arguably the most deranged work of genius that anyone has ever produced for television. (All black and white. Footage of nuclear explosions. And who can forget the Fireman rasping, “Got a light?” I certainly didn’t when I lost my voice for a few weeks two years ago and impersonated the Fireman on the phone to amuse friends.) And if you were fortunate enough to see Wild at Heart on the big screen, you know very well that it was as much an accomplishment of sound design as well as cinematic achievement. I’ve frankly never seen another movie in which the strike of a match sounded so crisp and alive. (I also strongly recommend this podcast interview with Lynch sound collaborator Dean Hurley.)

But I have to thank Lynch in another sense. I didn’t truly understand I was a weirdo and I really didn’t start to embrace this side of myself until I was in my mid-twenties. I grew up in an abusive household in which one was expected to conform to the Great American Lie when it came to culture.

Read The New Yorker every week. Be serious. Vote Democrat. Pay your rent and your taxes on time. Only involve yourself in the legal drugs. Get involved in relationships that led to marriage and 2.2 children.

God, I wince remembering how much I tried to be a hopeless square back then when this obviously wasn’t who I was. But I would make up considerably for my diffident youth in later years.

It was extremely clear that what I was doing creatively and what I believed in stood in sharp contrast to what I thought being an American should be — or, more accurately, what was drilled into me. I was nearly arrested in film school for demanding to be enrolled in a cinematography class that would give me access to 16mm film equipment that would permit me to shoot and cut celluloid. (I will always remember the vile and heartless authoritarian Larry Clark at San Francisco State, who did not even permit me to stick around and watch and help out after I asked to. Word of my punkish exploits circulated across campus, with many other students commending me on the cojones I had displayed, and I was thankfully allowed into the cinematography class the next semester with Catilin Manning, who was a kinder and far better teacher. Although when our group decided to spend our spring break spending every waking moment shooting film, returning to class with far more reels than any of the other groups, our film footage was so warped and unapologetically original that Manning just sat in her seat confused while all of us laughed. Her only feedback: “too grainy.”)

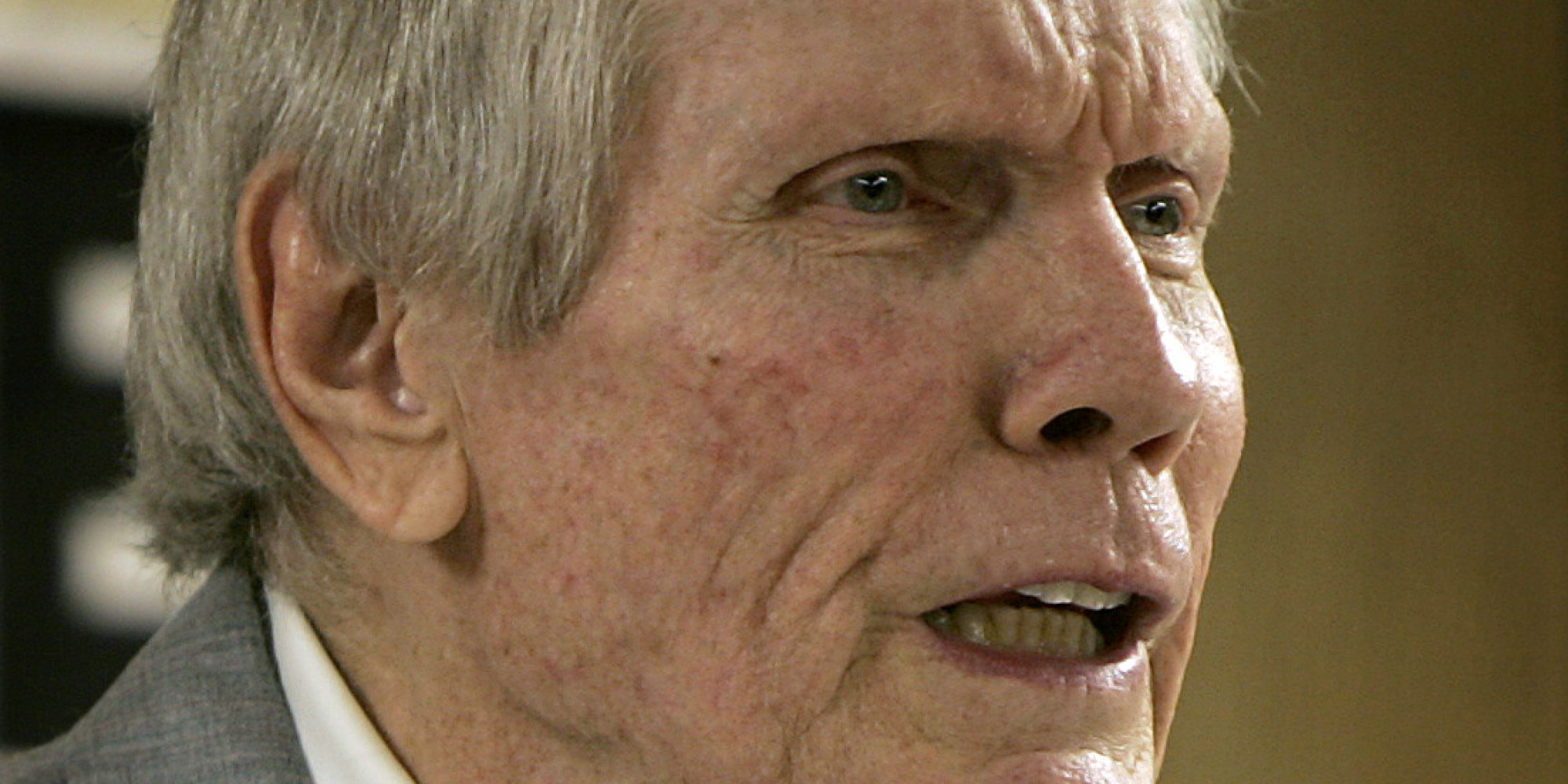

Years later, I became a cultural journalist entirely by accident. And I somehow had enough sway at the time to land an in-person interview with The Man Himself. (You can listen to the show here.) I met David Lynch at the Prescott Hotel (now the Hotel Zeppelin) on his birthday — January 20, 2007. I told the publicists that, out of a sense of great deference to Lynch, I would need to hold onto our conversation for the 100th episode. And they were gracious enough to not have any problem with that. Because Lynch was that important. He needed that round number.

I showed up to the hotel with a birthday gift — Tyler Knox’s Kockroach, Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis” told in reverse, which was the weirdest new release I could find at City Lights. And I cannot even begin to convey how kind and generous David Lynch was to me. You know the old mantra “Don’t meet your heroes”? Well, it did not apply at all to David Lynch. It turned out that he was a gentleman as well as a genius. He liked me a lot, laughing at my jokes and taking particular interest in my microphones. (Of course.) He even offered me some technical suggestions. Because he completely understood what I was doing with The Bat Segundo Show. He also spoke with me well beyond our allotted time. (As much as David Lynch’s voice was spellbindingly warm and quirky in clips, it was evermore so in person.)

As a personal rule, it had never been my practice to take photos after the interviews. I did my best to operate by a code of conduct that honored conflict of interest . But this was David Fucking Lynch. So I asked Lynch if he could take a photo with me.

And do you know what David Lynch did? He spent five minutes pacing around the hotel. He wanted this photo to be shot absolutely right. We finally found a spacious room that Lynch insisted had the best colors.

Then Lynch spoke.

“Say, Ed, I want you to put your arm like so. And since you’re a little taller than me, I’ll put my hand on your left shoulder. And it will be a good picture!”

Holy shit. I was being directed by David Lynch. But the man saw artistic opportunities in everything.

The kind publicist shot the photo that you see above.

I then shook David Lynch’s hand, thanked him, and told him that his work meant so much to me.

“Ed, I don’t think you’re meant to just be an interviewer.”

“What?”

He smiled and said, “You’ll figure it out.”

And then Lynch, in his impeccable suit, walked off. And that was it.

Of course, David Lynch was absolutely right. I did figure it out. The audio drama I have produced has changed my life, my writing, and my art for the better. It has made me a better person. I’ve discovered ideas and feelings inside me that I didn’t even know I possessed and that the brilliant actors involved with my independent project have instinctively picked up on.

And that unfathomable kindness — that casual manner in which Lynch saw something in me — meant everything to me and still does to this very day.

And that is why I took David Lynch’s passing so hard yesterday and why I am misting up even now as I write this.

Never meet your heroes? Well, in most cases. Certainly there are authors I’ve met who I’ve admired but who proved to be unkind. But not David Lynch.

Rest in power, sir. And thank you. I will never forget you and your great work.

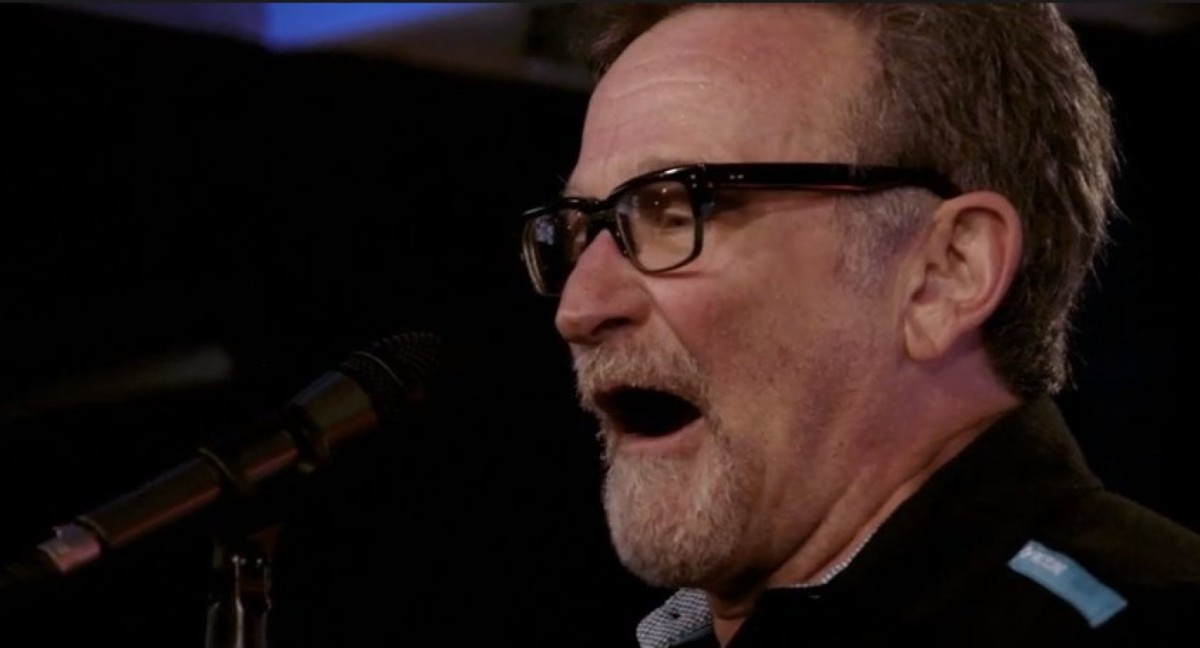

Who knows how many beasts and wraiths Robin Williams confronted? One was too many. This was a terrible and needless loss that, irrespective of Williams’s talent and stature, demands that we take several steps back. We know that Williams was

Who knows how many beasts and wraiths Robin Williams confronted? One was too many. This was a terrible and needless loss that, irrespective of Williams’s talent and stature, demands that we take several steps back. We know that Williams was