As this grim year draws to a close, the time has come to celebrate the best in books while the publishing industry celebrates the apocalypse. To read my thoughts on this year’s essays, you can head on over to The Millions, where my entry in A Year in Reading has just been posted. I’ll also be popping up later at Ready Steady Book, The Chicago Sun-Times, and The Barnes & Noble Review for their respective celebrations.

What follows is an alphabetical list of the books that, in my view, mattered the most in 2008. You’ll note that Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 is not on this list. Why is that? Yes, I took the book with me during my Thanksgiving vacation. But I made a deliberate decision to not read it until next year. I assure you that this was not some fashionably contrarian decision. The 25 pages I’ve read have indeed been quite interesting, and I remain confident that the remaining 875 pages will prove to be more gripping than the world’s most dependable dentures. I’m certain I’ll become one of those wild-eyed acolytes naming my firstborn son “Roberto” in honor of the great dead author who may or may not have been a heroin junkie. But I’m very much of the belief that good reading involves looking between the cracks and not always reading the obvious titles. So I have decided to put off 2666 until next year, where I can read this important novel without getting lost in the hype, thereby recusing myself from any possible ethical qualms. Besides, the book needs no love from me. It continues to be heralded as the Second Coming. And I’m waiting for the FSG publicists to work their magic and have Bolaño return unexpectedly from the grave.

What follows is an alphabetical list of the books that, in my view, mattered the most in 2008. You’ll note that Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 is not on this list. Why is that? Yes, I took the book with me during my Thanksgiving vacation. But I made a deliberate decision to not read it until next year. I assure you that this was not some fashionably contrarian decision. The 25 pages I’ve read have indeed been quite interesting, and I remain confident that the remaining 875 pages will prove to be more gripping than the world’s most dependable dentures. I’m certain I’ll become one of those wild-eyed acolytes naming my firstborn son “Roberto” in honor of the great dead author who may or may not have been a heroin junkie. But I’m very much of the belief that good reading involves looking between the cracks and not always reading the obvious titles. So I have decided to put off 2666 until next year, where I can read this important novel without getting lost in the hype, thereby recusing myself from any possible ethical qualms. Besides, the book needs no love from me. It continues to be heralded as the Second Coming. And I’m waiting for the FSG publicists to work their magic and have Bolaño return unexpectedly from the grave.

You will certainly not see the sleazy favoritism practiced by Sam Tanenhaus (I have tried to spread the love across multiple publishers), nor the gutless and tone-deaf choices on Jonathan Yardley’s list. The latter list surely presents a strong case for Yardley’s retirement. (In fact, you won’t find see any of their respective selections on my list.) But as a caveat, I must observe that I am friendly with a few writers on this list. This friendliness, however, has no bearing on my decision-making process. I am likewise friendly with a number of writers whose work I do not care for, but who I have always encouraged to write better. (And, no, I will not name those names. It’s hard enough to stay writing when the publishing industry remains locked in a crazed freefall.)

Selecting the best books of the year involves remembering the titles that have slipped from our memory. And I have tried to pick books that have done just that. The intriguing thoughts contained within Samantha Power’s fascinating biography, Chasing the Flame, for example, were occluded by the Hillary Clinton contretemps picked up on the gossip circuit, for which we have The Scotsman to blame. While Power’s book didn’t quite make the top ten cut, it is noted, along with a few other forgotten books, in the Honorable Mention section near the end. I must also point out that Andre Dubus III’s The Garden of Last Days, despite being around 550 pages, was one of those rare novels that I simply could not put down.

It occurs to me that this is a needlessly longass introduction for a top ten list. Well, no matter. I shall try to keep my thoughts on the ten titles confined to a paragraph each.

Nicholson Baker, Human Smoke: This was a much maligned book from a quirky talent who has had a long history of being misunderstood by the critics. Nicholson Baker never claimed to be a historian, but he did dig dutifully through newspapers, sufficiently demonstrating how some vital stories get lost in the jingoistic funhouse. Human Smoke dared to present an alternative series of events that, wherever one stands politically, made a very strong case that the events leading up to World War II (much less any history) need to be reconsidered through a different prism. Even if one disagrees with the premise that pacifism could have ended the war, there nevertheless remains a fascinating dilemma for the reader. Could it be that the established history we commonly accept isn’t nearly so comprehensive? What information are we throwing away? And what responsibility do we have in widening the floodgates decades down the line to account for our missteps in the present? (For more on this book, see the Human Smoke roundtable discussion that was conducted on these pages: Part One, Part Two, Part Three, Part Four, and Part Five. See also Bat Segundo interview.)

Sarah Hall, Daughters of the North: Recently, Gavin Grant helpfully reminded me that, as good as Daughters of the North is, there were plentiful feminist titles from the 1970s that went much further in their political ambition and sausage-slicing ideology. But Daughters of the North (known as The Carhullan Army in the UK) not only represents a natural evolution for Hall’s great writing talent, but it’s one of the few dytstopic novels of 2008 that, like Atwood’s bleak ball-busting pair (Oryx & Crake; The Handmaid’s Tale), I don’t believe will end up as a time capsule. (For more about this book, see my essay on Sarah Hall’s books for the Barnes & Noble Review. See also Bat Segundo interview.)

Sarah Hall, Daughters of the North: Recently, Gavin Grant helpfully reminded me that, as good as Daughters of the North is, there were plentiful feminist titles from the 1970s that went much further in their political ambition and sausage-slicing ideology. But Daughters of the North (known as The Carhullan Army in the UK) not only represents a natural evolution for Hall’s great writing talent, but it’s one of the few dytstopic novels of 2008 that, like Atwood’s bleak ball-busting pair (Oryx & Crake; The Handmaid’s Tale), I don’t believe will end up as a time capsule. (For more about this book, see my essay on Sarah Hall’s books for the Barnes & Noble Review. See also Bat Segundo interview.)

David Heatley, My Brain is Hanging Upside Down: I have been asked to contribute my thoughts for the Barnes and Noble Review‘s forthcoming best of books list. Since I am a man of honor when it comes to my professional duties, I feel that the right thing to do is to remain silent and mysterious . But I will fill in this blank and update this post when the link goes up. Needless to say, the book in question does fall alphabetically between “Hall” and “Hunt.” And I’m pretty sure that you can figure it out. (UPDATE: The list is now up. And you can also listen to the Segundo interview here.)

Samantha Hunt, The Invention of Everything Else: Like the work of Scarlett Thomas and Richard Powers, Samantha Hunt’s second novel is unapologetically concerned with communicating a sense of informative wonder to the reader. The book concerns Nikola Tesla’s last days in 1943, and a young chambermaid’s to understand him while her father tries to build a time machine to contact his dead wife. This unusual story, which also features several enjoyable glimpses of excitable people indulging in questionable pursuits (including an astutely realized old-time radio show), asks us to consider how much faith we should place in the crackpots of our world. Are great minds any crazier than the rapacious money men who exploit them? Would our nation be thriving right now if we dared to listen to those who are regularly discounted? (See also Bat Segundo interview.)

Samantha Hunt, The Invention of Everything Else: Like the work of Scarlett Thomas and Richard Powers, Samantha Hunt’s second novel is unapologetically concerned with communicating a sense of informative wonder to the reader. The book concerns Nikola Tesla’s last days in 1943, and a young chambermaid’s to understand him while her father tries to build a time machine to contact his dead wife. This unusual story, which also features several enjoyable glimpses of excitable people indulging in questionable pursuits (including an astutely realized old-time radio show), asks us to consider how much faith we should place in the crackpots of our world. Are great minds any crazier than the rapacious money men who exploit them? Would our nation be thriving right now if we dared to listen to those who are regularly discounted? (See also Bat Segundo interview.)

Nam Le, The Boat: I’ve long been unnerved by the continued lionization of writers who desperately cling to their MFA toolboxes like organization men who fancy themselves longshoremen because they have seen the sea. These types often mistrust their innate voices and fear their idiosyncrasies, and we are all the lesser for it. But early in the year, this book arrived in my mailbox out of the blue. I knew very little about it, but I began reading and found myself captivated by a rare talent who thankfully can’t be pigeonholed. Nam Le writes in multiple tones and multiple locations. This astonishing debut short story collection features heartbreaking portraits of transition (“Halflead Bay”), some playful postmodernism (the opening story features a character named Nam Le), and what I interpreted (I seem to have been the only one) as a muted and juicy satire of the New York artistic life (“Meeting Elise”). (See also Bat Segundo interview.)

Sarah Manguso, The Two Kinds of Decay: The celebrated poet Sarah Manguso suffers from a rare neurological disease called CIDP. As we learn in this short but stirring memoir, the disease is so rare that many doctors don’t quite know how to treat it. Manguso tackles both the literal and metaphorical ramifications of her personal dilemma, employing both high and low language, describing how she moved in and out of hospitals, and how dealing with this disease directly affected Manguso’s life. She learns, and we learn, that living is a scenario in which we must pay attention, and that paying attention, often in ways we aren’t entirely aware of, sometimes has unexpectedly moving results for ourselves and the people around us. (See also Bat Segundo interview.)

Stewart O’Nan, Songs for the Missing: The story goes that, over the years, Stewart O’Nan has made continued stabs at finishing this book, with the results often spilling over into other titles (such as last year’s excellent Last Night at the Lobster). But now that he’s finally completed it, O’Nan has accomplished something rather amazing here. This novel is ostensibly a mystery, in which an eighteen-year-old girl disappears and efforts are made by the family and a small Ohio town to find her. While this would seem to be a fairly typical storyline, you wouldn’t know this upon reading it. This book is one of the most astute presentations of human behavior and its unintended consequences that I’ve read this year — very much influenced by Richard Yates’s realism and rivaling Lee Martin’s The Bright Forever for a novel of this type. And that’s not an easy thing to do. I’ve found myself passing along this title to a number of writers who simply must study the way in which O’Nan embeds quiet details within this novel, and now I feel ethically obliged to pass along this title to you. (See also the Bat Segundo interview with O’Nan for his last book, Last Night at the Lobster.)

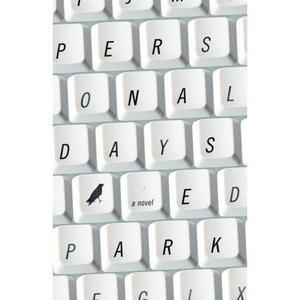

Ed Park, Personal Days: Long-time readers of this site will know that Good Man Park and I have carried out a strange interplay in the blogosphere. But I truly didn’t expect the Other Ed (or am I the Other Ed?) to knock this one out of the park. This office novel atones for Joshua Ferris’s overrated novel, Then We Came to the End, by offering crazy literary experiments (such as one section composed of a relentless pages-long sentence “written” by a worker who lacks a period on his keyboard), and permitting Good Man Park to flex his giddiness in fictive form. My only quibble with this novel is that Park may be self-censoring himself a tad about the horrors of office life, but it’s a small point that will hopefully be rectified in future novels. (See also Bat Segundo interview.)

Ed Park, Personal Days: Long-time readers of this site will know that Good Man Park and I have carried out a strange interplay in the blogosphere. But I truly didn’t expect the Other Ed (or am I the Other Ed?) to knock this one out of the park. This office novel atones for Joshua Ferris’s overrated novel, Then We Came to the End, by offering crazy literary experiments (such as one section composed of a relentless pages-long sentence “written” by a worker who lacks a period on his keyboard), and permitting Good Man Park to flex his giddiness in fictive form. My only quibble with this novel is that Park may be self-censoring himself a tad about the horrors of office life, but it’s a small point that will hopefully be rectified in future novels. (See also Bat Segundo interview.)

Ross Raisin, God’s Own Country: Raisin’s debut novel wasn’t nearly as well received on this side of the Atlantic as it should have been. But its sheer stylistic invention alone deserves high notice. Here is a writer who is not only willing to explore uncomfortable truths, but who has managed to use language in a way that permits us to empathize with a monster. The vernacular here doesn’t just form a parochial barrier. It may very well be one of the fundamental aspects that prevents us from helping the most troubled members of society. (See also Bat Segundo interview and my supplemental lexicon to many of the terms used in the novel.)

Leslie What, Crazy Love: This quirky short story collection has been almost completely overlooked by readers who look at the fantasy genre with the same frightened isolationism readily observed in George W. Bush’s move to a neighborhood terrified of non-Caucasian residents. That’s a great shame, because there are invaluable lessons here on how to take a wild idea and make it concise and enthralling. The collection contains unsettling allegories and gleefully imaginative premises. There isn’t a single story in here that doesn’t take some kind of narrative gamble. And while the dice-rolling doesn’t always pay off, it certainly remains hot in your hands. (See also my Washington Post roundup.)

Honorable Mention: Andre Dubus III’s The Garden of Last Days (Segundo), Elizabeth Crane’s You Must Be This Happy to Enter (Segundo), Jenny Davidson’s The Explosionist (Segundo) Jeffrey Ford’s The Shadow Year (Segundo), David Hajdu’s The Ten-Cent Plague (Segundo), Nick Harkaway’s The Gone-Away World (B&N Review), Samantha Power’s Chasing the Flame, Mark Sarvas’s Harry, Revised (Segundo), Brian Francis Slattery’s Liberation (Segundo for Spaceman Blues), and Neal Stephenson’s Anathem (Segundo).