(This is the twentieth entry in the The Modern Library Reading Challenge, an ambitious project to read the entire Modern Library from #100 to #1. Previous entry: Angle of Repose)

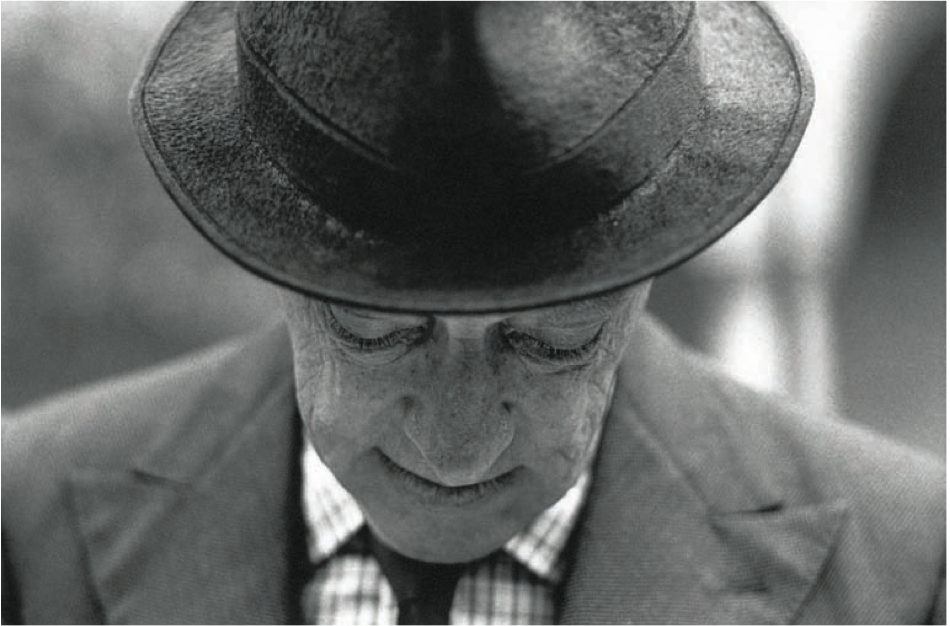

In 1995, Martin Amis insisted that Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March was America’s very reflection: a literary lodestone attracting all known bits of iron and reducing all subsequent ambition to blast furnace rejects. Six years later, Christopher Hitchens was more liberal about the dilemma: “I do not set myself up as a member of the jury in the Great American Novel contest, if only because I’d prefer to see the white whale evade capture for a while longer.”*

In 1995, Martin Amis insisted that Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March was America’s very reflection: a literary lodestone attracting all known bits of iron and reducing all subsequent ambition to blast furnace rejects. Six years later, Christopher Hitchens was more liberal about the dilemma: “I do not set myself up as a member of the jury in the Great American Novel contest, if only because I’d prefer to see the white whale evade capture for a while longer.”*

Augie March is indeed a fearsome masterpiece, but I’m inclined to side with Hitchens on the legacy question, for I would like to believe that some as yet unwritten book will change the game in ways now unknown. For now, we have Augie, which definitely stands as one of the 20th century’s heavyweights. I can state with certitude that this book will humble you, perhaps even wreck you for a time. Because nothing you read or write will feel this perfect.

I was so in awe of this novel that I was forced to read the two apprentice novels that came before (Dangling Man and The Victim), as well as Bellow’s recently published volume of letters. I needed to know that Bellow could fail like the rest of us. I needed this great human chronicler to be made more human. Dangling Man, in particular, proved to be an unexpectedly funny chronicle of a shut-in, with such declarations as “Hemmed in all day, inactive, I lie down at night in enervation and, as a result, I sleep badly.” And I was somewhat surprised to see Bellow take this book quite seriously. “I’m speaking of wretchedness and saying that no man by his own effort finds his way out of it,” Bellow wrote to David Bazelon in 1944.

But most literary people are self-important in their twenties. I swallowed Bellow’s middle period novels (Henderson the Rain King, Herzog, Humboldt’s Gift) during those years, but I never got around to reading the 600-page redwood that made Bellow a giant. I recall a few older strangers giving me approving nods on buses and subways. At the time, Bellow was still alive, but he was one of those writers you weren’t supposed to talk about. I had no idea why. It may have had something to do with Bellow siring his fourth child at the age of 84. I read his books anyway.

When I discovered that Dave Eggers was a huge Bellow fan (Eggers called Bellow “the person who I idolized more than anybody else” in an interview) and when I saw how The Adventures of Augie March had made Eggers’s fiction writing even more insufferable (You Shall Know Our Velocity anyone?), I became gravely horrified that Augie would have the same disastrous effect on me. (Again, I was in my twenties.) I did not want to become some smug asshole swimming in a twee cesspool. So I avoided reading Augie March in the same way that I avoided born again Christians, mass murderers, and rude moviegoers who bring loud plastic bags to crinkle.

This was a severe mistake.

No book can tell you how to live, but a great novel can kick your ass in the right direction. And I memorialize my youthful follies as minor regrets and as a plea to anyone under thirty to not make the same mistake. Read this novel at once!

The American temperament once prided itself upon initiative, innovation, and a sense of duty to anyone needing help. Augie March epitomizes all three ideals, but it is thankfully not without corruption or philandering or the need to hustle. After all, this book is set partly during the Great Depression. The gripping chapter where Augie takes his neighbor Mimi Villars in for an abortion is not only exceptionally daring for a book published in 1953, but, when Augie faces reprisals for his help, it reveals the peculiarly punitive American attitude steeped in moral judgment combined with partial knowledge of the facts.

Augie’s picaresque existence of finding odd jobs and falling in with odd characters and fretting over friends and losing lovers represents the kind of well-filled life serving in sharp contrast to today’s hipsters and go nowhere types. I am no longer in my twenties, but reading Augie did find me wondering how much time I was wasting and whether my energies needed to be focused more on the joy and love which drips in droves throughout this bawdy book.

Augie March is extremely well-observed, whether capturing a salon’s “oriental rugs that swallow sounds in their nap” or describing the way that Augie returns to Chicago to see a “gray snarled city with the hard black straps of rails” after his adventures in Mexico. It is wise, adventurous, heartbreaking, rueful, exciting, inspiring, but never mawkish. It is populated by indelible side characters such as the patriarch Einhorn, an ever-resourceful operator with a “fatty, beaky, noble Bourbon face” who serves as Augie’s father figure, the querulous Grandma Lausch who tends to the March home when Augie’s mother cannot, and Mintouchian, the avuncular Armenian who doles out some rules for living. Even Trotsky makes a cameo.

And then there’s Bellow’s nimble linguistic dexterity, in which his gift for description merges seamlessly with Augie’s expansive wisdom:

But maybe that spicy, sumptuous fish-gravy odor that belonged to the past made me too much of a critic of the present moment, exaggerating Mama’s difficulties and imagining that the Gulistan and the drapes were the softenings of a cage.

This passage comes late in the book, when Augie is wondering if he has been altogether decent to his debilitated Mama and to his developmentally disabled brother Georgie, locked away and betrayed by Augie’s older brother Simon, who spends most of the book with a missing tooth. It’s especially wistful that this is the ultimate cost of Augie’s raucous adventures: that the broken family should be so physically broken and that dear relatives should be schlepped away to institutions.

Since Augie may be fated to start a family of his own, his Adventures could be read as a Rosseau-like confessional. Rosseau hoped to make his way into heaven by telling all. For Augie, perhaps family and love may be the empyrean reward. When Augie says in the final paragraph that he’s “a sort of Columbus of those near-in-hand,” we realize his terra incognita may not necessarily be of the “American, Chicago-born” category, but more concerned with stretching the soul. And if his soul has already stretched across decades, why wouldn’t it stretch further?

* — It may be worth noting that Amis, who befriended Bellow, took Hitchens to meet the great genius. But the two distinctive writers got a bit contentious. From Bellow’s August 29, 1989 letter to Cynthia Ozick:

During dinner he mentioned that he was a great friend of Edward Said. Leon Wieseltier and Noam Chomsky were also great buddies of his. At the mention of Said’s name, Janis grumbled. I doubt that this was unexpected, for Hitchens almost certainly thinks of me as a terrible reactionary — the Jewish Right. Brought up to respect and to reject politeness at the same time, the guest wrestled briefly and silently with the louche journalist and finally [the latter] spoke up. He said that Said was a great friend and that he must apologize for differing with Janis but loyalty to a friend demanded that he set the record straight. Everybody remained polite. For Amis’ sake I didn’t want a scene. Fortunately (or not) I had within reach several excerpts from Said’s Critical Inquiry piece, which I offered in evidence. Jews were (more or less) Nazis. But of course, said Hitchens, it was well known that [Yitzhak] Shamir had approached Hitler during the war to make deals. I objected that Shamir was Shamir, he wasn’t the Jews. Besides I didn’t trust the evidence. The argument seesawed. Amis took the Said selections to read for himself. He could find nothing to say at the moment but next morning he tried to bring the matter up, and to avoid further embarrassment I said it had all been much ado about nothing.

Hitchens appeals to Amis. This is a temptation I understand. But the sort of people you like to write about aren’t always fit company, especially at the dinner table.

Next Up: Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited!