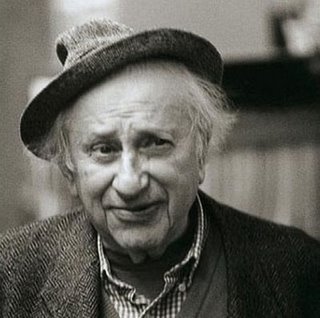

Studs Terkel is dead. And the radio world as we now know it has been permanently altered.

When I heard the news, I felt a horrible lump within me bunch up and plummet to the floor. I had been talking up Terkel only yesterday, openly contemplating to friends whether today’s podcasters and staid NPR types — who seemed narrowly concerned only with those caught within their fifteen minutes of fame — would even come close to Terkel’s deep and wide-ranging interest in people of all types. The only guy among my generation who has come close to Terkel is possibly Benjamen Walker, whose excellent Theory of Everything program is now sadly defunct. And over the past few months, I’d likewise been pondering whether I had an obligation to expand the range of my own program to include more people outside the cultural world.

When I heard the news, I felt a horrible lump within me bunch up and plummet to the floor. I had been talking up Terkel only yesterday, openly contemplating to friends whether today’s podcasters and staid NPR types — who seemed narrowly concerned only with those caught within their fifteen minutes of fame — would even come close to Terkel’s deep and wide-ranging interest in people of all types. The only guy among my generation who has come close to Terkel is possibly Benjamen Walker, whose excellent Theory of Everything program is now sadly defunct. And over the past few months, I’d likewise been pondering whether I had an obligation to expand the range of my own program to include more people outside the cultural world.

Terkel demonstrated with his great journalistic genius that everybody had a hell of a story, that everyone was part of history, and that with enough curiosity, you could find the insight in damn near anyone.

He documented working people in a way that nobody on radio has been able to come close to in the past several decades. He provided an invaluable history of the Great Depression. One could listen to any of Terkel’s interviews and feel immediately humbled, almost insignificant by comparison. He brought so much life to the interviewing form, unfurling so many unexpected details in his subjects. The train hopper who described the way in which he packed hot dogs into his clothes to avoid starvation. The behavioral specifics devised and brought about by existing within an epoch.

Anybody interested in people would do well to revisit Terkel at length. This was a man who changed the rules of oral history. This was a man whose prolific professionalism simply asked us to look deep inside ourselves, and see the people around us. And I don’t know if we’ll see the likes of him again for some time. But his passing signifies that we all have to do much better.

(Image: Robert Birnbaum)