Behind Locked Doors (1948): I’m almost certain that Sam Fuller found some inspiration in this movie for his masterpiece, Shock Corridor. Behind Locked Doors doesn’t offer Fuller’s cultural scope, but it is a strangely entertaining B-movie, with typical yet solid noirish cinematography by Guy Roe. Richard Carlson’s a private eye hired by a San Francisco journalist (Lucille Bremer, who retired from acting shortly after making this movie) to hole up in a sanitarium, pretending he’s insane, so that he can determine if a crooked judge is hiding out there. He’s given the DSM manual, flips through it, and points to “manic depressive” because he “kind of likes it.” The book is thicker than almost anything published by the Library of America, but it’s something of a relief to know that finding insanity credentials is this easy.

In the sanitarium, Carlson befriends an employee with the unlikely name of Hopps (played by the uber-thin Ralf Harolde), who appears here as the Confidant with the Golden Heart. It’s clear early on that Hopps will find his redemption for being such a nice guy. That’s the way these B movies work.

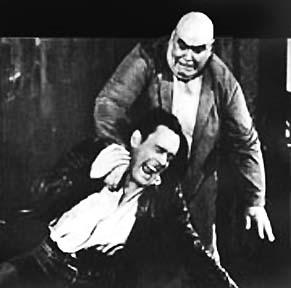

But the true genius (or, in this case, mad serendipity) of this movie is Tor Johnson. Johnson, perhaps best known to cinephiles as a kitschy behemoth frequently employed by Ed Wood, somehow stumbled upon the role of his career. In this film, he’s a boxer locked in a private ward. The minute that someone starts hitting the bars of his cell with an ingot, Johnson stirs to life, tearing his chair into pieces and punching at invisible opponents, somehow identifying the sound as a bell. Never mind that bell in a boxing match only rings when a round has concluded. He’s referred to only as “the Champ.”

But the true genius (or, in this case, mad serendipity) of this movie is Tor Johnson. Johnson, perhaps best known to cinephiles as a kitschy behemoth frequently employed by Ed Wood, somehow stumbled upon the role of his career. In this film, he’s a boxer locked in a private ward. The minute that someone starts hitting the bars of his cell with an ingot, Johnson stirs to life, tearing his chair into pieces and punching at invisible opponents, somehow identifying the sound as a bell. Never mind that bell in a boxing match only rings when a round has concluded. He’s referred to only as “the Champ.”

The reasons for Johnson’s madness are never explained. And I would contend that this is a good thing. Johnson has little in the way of range and this lack of detail provides an unexpected enigma. He’s a big guy capable of picking up people and tossing them over stairwells. An easy enough task for a cinematic brute. But Johnson has a methodical, soporific way of stumbling across the screen that I’ve always enjoyed. It more than makes up for his lack of thespic abilities, limited to raised eyebrows and a face crunched up in unconvincing community theatre horror.

Hopefully, it’s clear enough from my description that the plot is utterly ridiculous. But the film is a brief 62 minutes. Director Oscar Boetticher keeps things moving along at a brisk pace. The dialogue is hard-boiled. This movie has enough courage to bring a hurried austerity to lines like “It’s almost six and I have a dinner date.” Alas, such courage results in unexpected camp.

But if you’re drunk or you have a short attention span, Behind Locked Doors is that questionable morsel illustrating that even a heavy-handed fruitcake can come across as unexpectedly beatific.