The Thomas J. Cahill Courthouse, an edifice erected between 1958 and 1960 that houses the San Francisco Criminal Court, is a stark and, for the most part, featureless seven-story building composed almost entirely of cement and mortar. If I had to name an architectural style, I’d peg it as New WPA Revival.

Its outside walls are unpainted and unwashed. There’s nothing in the way of cornices or garrets. No fluted columns. Not even Justice, with her blindfold and her scales, makes a cameo engraving. In fact, there’s nothing remotely Roman about the place. It is a gigantic box that ensnares and entraps, spewing out a small collection of suits and inveterate smokers hobbling in the daylight. I saw one African-American woman in her forties huddled over in tears, her arm clutching a rail for support. There was no one to answer her call. Justice had been served. As a prospective juror called in to perform my civic duty, an obligation I had postponed, avoided and ignored for too long, I suddenly felt uncomfortable about meting out hard fate.

To enter the building, a visitor must walk through one of three pairs of doors. And because government minimalism is at work, above each door is a flagpole — three flags in total, identifying the nation (United States), the state (California) and the city (San Francisco), lest the visitor think he is in Cleveland, Ohio. The rectangular motif has been applied to clover hedges which run their way around the building’s perimeter, never daring to impede their rectilinear nature with a curve. Government, at least as it pertains to the administering of criminal justice, is resolutely square. I had to wonder whether Thomas J. Cahill approved.

There is, however, the great Seal of the City to the right of the courthouse entrance. A dedication just below this reads: TO THE FAITHFUL AND IMPARTIAL ENFORCEMENT OF THE LAWS WITH EQUAL AND EXACT JUSTICE TO ALL OF WHATEVER STATE OR PERSUASION. THIS BUILDING IS DEDICATED BY THE PEOPLE OF THE CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO.

Well, that’s all quite nice, but while the courthouse’s purpose is clearly and broadly addressed, I felt a little funny about a dedication plague that didn’t bother to include a recipient.

But not all is lost in the government spending department. Considerable money appears to have been siphoned for the lengthy handicapped ramp which leads up to the entrance in two diagonal swoops. The ramp has strayed from its initial purpose to fulfill the needs of stragglers, city workers, underpaid paralegals wheeling in pivotal papers and those with spare time.

I saw the flash of many an Armani, but these high-priced career men sped down the steps with an urgency that rivaled Boston Marathon runners. If they had clients, their arms were draped protectively around them and their heads were arced in the client’s direction, as if expecting a Chronicle city beat photographer to snap a few images to cripple character. If they didn’t have clients to nurse, they had cell phones. I timed a few attorneys leaving the door and, based off of five samples, I determined that the mean time between an attorney fleeing through the doors and whipping out a cell phone was 2.3 seconds.

After taking in this tableau, with five minutes to spare, it was time to make my way through the doors and determine my fate. Would I be on a four-week jury? Would I be excluded because of a peremptory challenge? Would I be shuffled from court to court like a human yo-yo? Would I fulfill my longtime dream of becoming the outstanding Henry Fonda figure in a room without air conditioning? I had ideas, images, and a commitment to impartial truth. The night before, I had decided to accept the fate of the criminal court gods and serve as a juror, if required. So that morning, I shaved.

I passed through the metal detector with flying colors. No beeps to speak of. I said hello to the security guard. He grunted in acknowledgment. No prob. This was easier than an airport.

More lawyers, more expensive suits, more briefcases and clients. And all this set against a vestibule of pinkish marble. I found the elevators and headed to the third floor.

It was easy to find the prospective jurors. I knew them by their confused gait, the way they constantly looked around. Their heads were all cast slightly to the floor. Who needed directions to the Jury Assembly Room when you had so many greenhorns that made the way so easy and identifiable?

The halls were now wider, but as unadorned as the outside walls. Square blocks of fluorescent cast muddy reflections on the murky green marble floor. I wondered how this place looked at night.

I went to the desk. There was a neat stack of envelopes from the day’s mail. Prospective jurors who had bowed out. The clerk, business as usual, asked me to fill out a form I had completely forgotten about. And then I was off to the races, waltzing into the waiting room.

I went to the desk. There was a neat stack of envelopes from the day’s mail. Prospective jurors who had bowed out. The clerk, business as usual, asked me to fill out a form I had completely forgotten about. And then I was off to the races, waltzing into the waiting room.

The first thing that hit me was the indelible silence. The room was packed with about 150 people, but only a few people chatted on their cell phones. And even then, the rustling of a turned newspaper page dwarfed these mutterings, which were mainly business-related. Taken with the flattened puke-brown carpet, which looked and smelled as if it had seen at least a decade of foot traffic and infrequent vacuuming, the atmosphere spawned a contagious asceticism.

There were orange chairs with horrid black piping for armrests. A dying plant was situated near the windows. The same weak sunlight permeated through dusty panes onto a few round tables. On the opposite side of the room, I was amused to see a remarkable collection of empty wooden coat hangers hanging on a long rod that extended some twenty feet horizontally. The funny thing was that everybody wanted to hold onto their coats, presumably hoping to spend as little time as possible should they be one of the lucky bastards who got away.

No one smiled.

What did people do? They read newspapers. They stared into space. They tried to sleep and failed. The look of the bored was something like this: head sinking as far as it would go into the thin cushions, legs spread far out onto the floor, limbs clutched protectively into their chests. I watched one woman spend fifteen minutes folding a plastic bookstore bag, trying to determine the exact configuration it needed to be folded and inserted into her purse. Only after this elaborate ritual did she crack open her newly purchased trade paperback. I saw a sixty year old man cough repeatedly, while applying his pen to a thick legal agreement. He underlined every other word.

Time slows down in the jury assembly room. People have plenty of it here. Even when you’re prepared (and I had six books to read in my bag in case they locked the doors for a week), there is something about the process of indeterminate waiting that forces an almost total collapse of the synapses. After two minutes, the brain percolates again and finds things to do. It has to. Because the clock is ticking. Slowly, but ticking nonetheless. After this, there begins the silent bonding through furtive glances. That’s all you can do. Because making eye contact with strangers would, of course, cement your reputation as a closet stalker.

I was surprised to see that nobody looked particularly slipshod. Nobody wore T-shirts or nose earrings or shaved swastikas into their scalps. They stuck by the playbook and awaited their fates.

I wondered when it would begin. Two vending machines, the sole source of sustenance, remained untouched. A mid-sized television rested front and center. I saw a small window partition in the distance with three plastic snowflakes taped on and two ratty celebratory Xmas strings (one red, one green) hanging from the lintel. They both drooped and resembled loose nooses. There was a paucity of signs. No “Thank you for fulfilling your civic duty.” No “Clerks are sexy. Ask up front for a date.” Nothing to energize a Law & Order junkie. I was quite surprised to see a painting of some important local figure I couldn’t identify in a coffin-shaped frame. And I wondered if this was the décor to get people excited about democracy. Ultimately, there was nothing to think about but the cold hard process of waiting. This vexed most and comforted others.

I opted to read.

And then I heard the voice of the orientation lady. I didn’t know where it came from and wondered at first if I was hallucinating. But as my eye spent two minutes surveying the room, I realized that the flat, vaguely sing-songy voice was coming from a flat, vaguely sing-songy lady, essentially repeating what was printed on the jury summons.

We then watched the orientation video.

“California. Our state is a place of natural beauty and harmony! The best state in the nation!”

Video images of roaring waves colliding against currents and yuppie couples holding hands in Napa.

“But…not always.”

Sudden image juxtaposition. Criminals! People getting arrested. Oh no! The world isn’t as harmonious as we thought!

“We have disputes.”

No shit?

“And that’s where justice comes into play.”

Dissolve into footage of smiling attorneys, smiling bailiffs, smiling judges, the nice, relatively normal actors assembled for the industrial. You’d think it was a beer commercial. But where were the bikinis? This was followed by everyday Joes offering testimonials about how jury duty changed their life.

I wish I could tell you that I ignored this silly video, but I was strangely hooked. It was too surreal. This was the courtroom equivalent of the “It’s a Small World” ride at Disneyland. But where that ride failed to persuade me that the world was a safe and sacrosanct place, the minute that the video offered an image of the Constitution, the moralist and the political junkie in me cried out, “Fuck yeah!” It seemed that where commercials had completely failed to get me to purchase their products, this video, with its explicit reminder that this country’s founding documents referenced trial by jury several times, got its tenterhooks into me. Bring it on!

The first jury pool names was read. My ears pricked up. I was fascinated that one of my city supervisors’ names was called. Nyah nyah! In your face!

And then they called my name.

Shit. So much for orientation propaganda.

I walked down a stairway with about a hundred other people, thinking from the asbestos peeling out of the walls that I was going to be lead into a bomb shelter or a gas chamber. But instead I entered a room – what’s referred to in the trade as a “department.” The place where trials happen and ineluctable sentences are executed.

This room was all wood, all the time. The same paneling pervaded every square inch of the place, much as the pink marble had in the vestibule and the concrete had on the outside. The No Adornments policy echoed its way into the inner sanctum, as had the flag motif. On each side of the judge’s seat, there was the United States flag and the California flag. And just behind this was the City’s seal. The jury seats were on the left, a chalkboard and a calendar, with orange and green highlights for holidays and weekends was on the right. Above the jury seats were several numerical printouts corresponding to the seats. (Please let me be Juror #8! Please let me be Juror #8!)

Then a small man introduced himself. He was the clerk of this establishment and a stand-out guy. As people came in, he said, “Good afternoon. Come on in please.” He made sure everyone had a seat. He talked very slow. I didn’t see a judge, a defendant, attorneys, or a bailiff. Where were they? We were prospective jurors, dammit! We had sacrificed time, money, and late return fees at Blockbuster to serve democracy. Didn’t we deserve some kind of reception?

Apparently not. The clerk took roll call. People announced that they were “here.” When they called “Champion,” at that point, I had to rock the boat a bit. Remembering how annoyed my seventh grade English teacher was with “Present” (the snarky bastard’s alternative), I used this very same word almost two decades later. In a courtroom, no less. There was a slight pause from the clerk, a modest glance up from his roll call sheet, and then a continuation of his ceremony. I was honored that other people took my lead and answered “Present” too, demonstrating prima facie evidence that an corruptive adolescent streak can survive into one’s thirties.

Then we were sworn in. Collectively. I was disappointed that a Bible hadn’t been served up. Because I was prepared to serve up my atheist credentials and ask for a copy of Ulysses or The Canterbury Tales.

Finally, the cavalry arrived. The prosecutor, the defense, the defendant, the defendant’s mother. I particularly liked the bailiff, who was a large man with a bushy moustache. When he set down on his chair and placed his hand to his head to stave off what was either boredom or a headache, we were blood brothers immediately.

Counting the number of seats per row and the number of rows, I quickly computed that I was one of a hundred jurors. By my lousy math, I figured that there was a 1 in 8 chance I’d get picked. Not bad for a guy vacillating between a copout and civic duty.

Then the judge came in. She was friendly, well-spoken, and laid it all out for us. The trial was afternoons, two to three days a week in light of the holidays. If we could serve, we needed to come back on Monday. As jury duty goes, that’s an extremely equitable schedule. But that wasn’t what clinched my decision to stay.

I looked at the defendant and the prosecutor again. The defendant was very, very black. The prosecutor was very, very white. In an instant, civic duty and a judgment based exclusively on the evidence won out.

I opted to return on Monday. Not even the supervisor could promise that much.

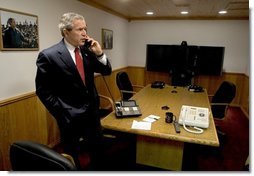

This morning, I spoke with the leaders of India, the nation that ends with Lanka, Thailand (where I told them to stop with the pad stuff, which is too spicy for a Texan’s stomach) and Indonesia, and expressed my condolences while trying to suppress my own personal laughter. And if you don’t believe how manly I was or that I actually made these telephone calls, I invite you to look at this picture. Do you see how in command I am? There are not one, but two phones on the table. And there are some papers too that I’m using to get that whole Lanka thing down. You see? I’m presidential.

This morning, I spoke with the leaders of India, the nation that ends with Lanka, Thailand (where I told them to stop with the pad stuff, which is too spicy for a Texan’s stomach) and Indonesia, and expressed my condolences while trying to suppress my own personal laughter. And if you don’t believe how manly I was or that I actually made these telephone calls, I invite you to look at this picture. Do you see how in command I am? There are not one, but two phones on the table. And there are some papers too that I’m using to get that whole Lanka thing down. You see? I’m presidential. I went to the desk. There was a neat stack of envelopes from the day’s mail. Prospective jurors who had bowed out. The clerk, business as usual, asked me to fill out a form I had completely forgotten about. And then I was off to the races, waltzing into the waiting room.

I went to the desk. There was a neat stack of envelopes from the day’s mail. Prospective jurors who had bowed out. The clerk, business as usual, asked me to fill out a form I had completely forgotten about. And then I was off to the races, waltzing into the waiting room.