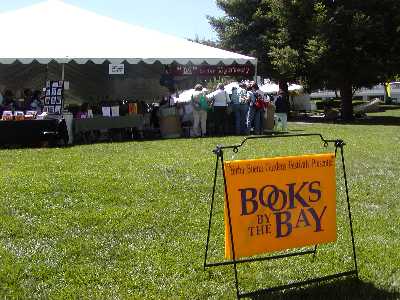

It was roasting, at least as San Francisco weather goes. Sunshine hit the tents and the grass and the hatted heads of a mostly older crowd — some of them aspiring writers, some of them dedicated bibliophiles, some of them trying to figure out what the sam hill was going on and picking up a book or three.

It was roasting, at least as San Francisco weather goes. Sunshine hit the tents and the grass and the hatted heads of a mostly older crowd — some of them aspiring writers, some of them dedicated bibliophiles, some of them trying to figure out what the sam hill was going on and picking up a book or three.

This year, the annual Books by the Bay was not, like previous affairs, technically adjacent to the Bay. Perhaps Books Sorta By the Bay or Books By the Bay (If You Walk A Half Mile) would have been a more apposite appellation.

Nevertheless, this year drew, from my eyes, about five hundred souls, most of them seeking the air conditioning within the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts.

I had arrived later than I expected, due to events pertaining to the previous night (with an insomnia chaser). But I did manage to catch the tail end of Kevin Smokler’s panel.

WRITING IN AN UNREADERLY WORLD

Panelists:

Adam Johnson was supposed to show up. But he could not be seen. Either he had discovered invisibility or he had an unexpected engagement.

When I got there, Soehnlein was talking about how McSweeney’s had specifically lowered the price to appeal to younger readers. McSweeney’s had also recently offered a ten-book bundle for $100 for this very reason.

Michelle Richmond and Kevin Smokler contemplate the precise moment that they should respond to an audience question.

|

Smokler pointed out that he was initially resistant to have Bookmark Now come out in paperback (instead of hardcover). But he came around to understanding that this was the right thing to do, given that the book was aimed at younger audiences. It was pointed out that Richard Russo’s first book, Mohawk, came out in paperback only. He also expressed hope that there would be more fan fiction based on characters (along the lines of the fan fiction that Neal Pollack alluded to in his essay), because fan fiction was an indicator of sales.

Soehnlein noted that he had wanted to do a virtual book tour for The World of Normal Boys, but he couldn’t persuade his publisher because the publisher couldn’t quantify sales. He suggested that word-of-mouth was just as good as a high profile NYTBR review.

Smokler noted that because of fan fiction and online forums, it’s become more acceptable to evangelize for books.

Michelle Richmond hoped that someone would simply wear a sandwich board displaying the title of her book.

A question was asked about where the book world would be in ten years.

Smokler hoped that every bookstore would be wirelessly linked and that instant reviews would be available. He hoped that every author could have a website and an email address. He didn’t want to see readings as dull affairs. Richmond hoped that every city would have the same indie bookstore scene that San Francisco does.

MORE THAN JUST A JOB

Panelists

The panelists introduced themselves. I don’t know who the moderator was, but he was an able guy who maintained an appropriate amount of levity, which offered a sharp contrast to the lackluster “Life Experiences” panel that I attended later that afternoon (more below).

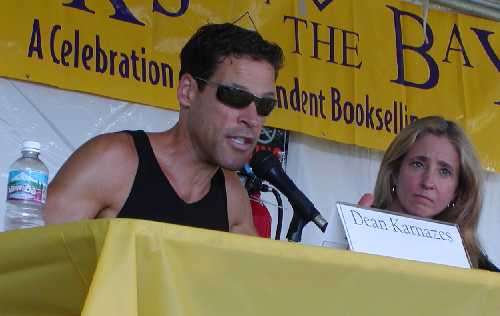

Dean Karnazes, frightening the crowd (and wooing Blair Tindall, right) with tales of his long-distance marathon running.

|

Karnazes was a very muscular man who had apparently written a very muscular book, Ultramarathon Man. He had several muscular achievements under his belt, including running nonstop for 262 miles. He wore a black tank top and sunglasses. I could only surmise that he wouldn’t reveal his eyes because we would see traces of the gamma radiation that had no doubt assisted him in running for such an inhuman distance.

Blair Tindall once played the oboe for a living, but grew tired of it, producing a memoir about the scandalous culture (Mozart in the Jungle).

Phil Done’s memoir was 32 Third Graders and One Class Bunny, which covered one year teaching thirty-two third graders.

Betsy Burton is an independent bookseller in Salt Lake City, Utah. Her experience running a bookstore named The King’s English is covered in a book, predictably called The King’s English.

The moderator asked if the memoirists regretted putting certain details into their books.

Burton said that she didn’t regret putting in an incident of cocaine being sniffed on her toes. She’s not a drug user. But her mother, by contrast, regretted thsi. She suggested never starting a bok tour in a small town. It took her a long time to decide what to put in and what to keep out. She did have one light-hearted paragraph about sex that was taking completely out of context and was intended as levity.

Burton had once been a business reporter of the older and more respectable incarnation of the San Francisco Examiner. Her lawyer had perused the book and decided upon who needed to be disguised by psuedonyms.

Karnazes apparently wrote his book by speaking into a digital recorder while running at night. He would actually dictate while doing this and then type his notes into his computer. The transcription proved difficult because there was considerable panting which occluded comprehension. He decided upon graphic descriptions of toenails breaking off and crawling for the last mile to make the experience more real to the reader.

Done had to change the names of his students. However, close colleagues begged him to keep their names in. His memoir includes drafts of letters that he never sent to parents.

Burton pointed out that there were certain writers she did not mention by name. However, she did observe one writer reading her book in a store, starting to mutter and then starting to swear and then starting to swear some more. This writer slamed the book down.

Karnazes: Running is “my way of being my best.” Free food, however, at the aid station was also a motivation. It was pointed out that Karnazes was named one of the 100 sexiest men in sports by Sports Illustrated. Karnazes responded that, actually, he had been in the top ten.

Blair Tindall takes out her oboe, putting Phil Done under her trance. |

Tindall started off as a frustrated but fairly successful musician in New York. She felt irrelevant. She didn’t recognize sexual harassment as it was happening. The oboe wasn’t enough to fulfill her life. So she went to Stanford for journalism school. She then learned that of the 11,000 music graduates, there are only 250 jobs. The economic reality of the music world dawned upon her and she wanted to bring a more populist approach to the classical music world and remove the fantasy.

Ms. Tindall then brought out her oboe and played it for the crowd.

Done wrote to share stories of what was really happening in the classroom. He wanted to give teachers something to identify.

Burton hoped that her book would change the indie bookselling landscape a bit. She runs a bookstore in Salt Lake City and she’s not a Mormon.

A question involving technology came from the crowd. Karnazes mentioned that he played back some of his running recordings for the BBC. Tindall used a pen that Xeroxed a passage line by line during her research.

Amazingly, Kazares kept a crazed regimen when writing his book for nine months. He slept for four hours each night, while also running at night, writing the book, raising a family, and running a company. (He’s President of Good Health Natural Foods.) He ran competitively during his freshman year in high school. Then he hung up his shoes. On his thirtieth birthday, he was at a pub with friends and decided on a whim to run thirty miles for his thirtieth birthday. He ended up running all the way from the Marina to Half Moon Bay. Halfway through, he sobered up and wondered what the hell he was doing. But he did make it the thirty miles. Kazares was also the first person to run around the world naked.

LIFE EXPERIENCES

Panelists:

Perhaps it was the solemn audience or the fact that I had just come from a pleasant outdoor atmosphere where people were laughing and excited about books. Or perhaps it had something to do with the inanity of the questions from moderator and audience. But the Life Experiences panel was, for the most part, a bust, resorting to the same tired memoir-as-catharsis/memoir-as-therapy trope that one can get from reading any self-absorbed newspaper column.

I should point out that despite previous reports, Solnit was not to blame. In fact, I’d venture to say that, in this venue at least, Solnit’s associative riffing worked in the panel’s favor, representing a concerted effort to steer the conversation away from the stiff and the tired adulations being thrown around like stale popcorn. Unfortunately, the moderator, whose name I do not know, was determined to encourage the most conventional questions known to humankind.

For example, let’s take a rudimentary question such as “What distinguishes fact from fiction?” Here were the answers:

SOLNIT: Part of the revolution involves contesting official history. Thus, a memoir involves witnessing other stories.

KRAUS: Mark Twain once wrote, “Fiction has to be true.” “It’s only what I know from where I stand.”

GUILBAULT: “If I wrote it as fiction, I’d be angry. But in memoir form, it’s how it happened.”

DENG: “I wasn’t a writer until I told the truth.”

SANTANA: “I loved the journey of telling the truth!”

Rebecca Solnit. |

And that was essentially how it went down for forty-five minutes. We can see from the above that Solnit and Deng’s answers were the more incisive of the bunch, while the rest wallowed in Writer’s Digest cliches. I’m sorry to report that it was these two who had things of value to say, while the remaining three writers, whatever the plaudits of their written work, kept riding the Memoir Empowered Me line. To even bother to construe my notes here would be futile and silly.

I’ll only say that at one point, Deborah Santana noted how “hard” it was to be “in Carlos’ shadow for twenty years” and that this role threatened to subsume her identity. My heart bleeds, Deborah. Let’s compare this sentiment with Alephonsion Deng (and his brothers), who described how painful it was to remember the mundane details of a life in refuge from the Sudan atrocities eating squirrels and drinking urine as a young boy.

FIRST NOVELISTS

Panelists:

First off, the less said about Guthmann’s moderation, the better. However, the more said about Joshua Braff, the better. Braff pretty much stole the show. He was full of enthusiasm and valuable tips, even when the audience was feeding the panel with questions about the realities of being a writer (to which Guthmann offered an insensitive and misleading “Miracles do happen” pronouncement, citing Elizabeth Kostova’s one-in-a-million windfall).

Braff suggested that if you’re writing a book, find a Jewish angle. “You don’t even have to be Jewish,” he said. One of the reasons his novel, The Unthinkable Thoughts of Jacob Green had been such a hit was because he had appeared at several readings during Jewish Book Month. He had managed to find a cultural center in nearly every city to speak of and was booked solid for a long time. Word got around. He was “happy that I was tenacious.”

Elizabeth McKenzie and Joshua Braff.

|

Braff also noted that editors call writers very frequently to ensure that they’re waking up and working on the book, the concern being that they might be another Charles Bukowsi.

When Schuyler was first starting out as a writer, she said that being patient about “the right time to be judged” was beneficial for her. She had sent out emails to book clubs, coordinating discussions of her novel, The Painting, with appearances and email dialogues.

A question was asked about how to go about getting an agent. Many of the answers are already common knowledge, but I reproduce them here for the benefit of any aspiring writers who may be reading this report.

McKenzie said that she was holed up at home and was fortunate enough to find an agent who liked her work. (Her agent, as it turns out, is Kim Witherspoon.) After this, everything happened very fast.

Braff said that he had contacted a few agents, but hadn’t heard back from them for a long time. So he called them. A few called him back apologizing and saying that they wee going to read his book now. He said that if you are writing fiction, you need a complete manuscript. If you have a nonfiction, you can write a great book proposal and get the money up front. He suggested to the many aspiring writers in the crowd that they contact agents of authors who they liken their work to. If necessary, you can call a publisher and find out who the author’s agent is.

Schuyler suggested a three-paragraph cover letter: the first paragraph being a summary, the second expressing qualifications and the third describing how to be cotnacted. Schuyler had approached seven agents before stumbling upon one.

Before she was a writer, McKenzie said that she wanted to be a journalist as a young girl because she was enamored of 60 Minutes. However, because she distorted everything, she found herself turning to fiction.

Schuyler had initially been intimidated by writing. She studied everything else before going into journalism. This taught her to write fast. But she got tired of writing other people’s stories and turned to fiction. She had, in fact, a law degree and passed the bar. She likened the first draft of her novel (680 pages) to all the knowledge that she had to keep inside her head during the bar.

Braff had taught English in Japan and then began writing stories. He took extension classes and described how valuable free writing was for him, likening it to working out. He would meet with a group in a coffeehouse and all would continuously write for five minutes — never stopping with the pen. Then the pieces would be read aloud without judgement. Then they would write for ten minutes, repeat, and then perform the exercise for fifteen minutes. Braff also noted that people didn’t always have the opportunity to hone their gifts because of life circumstances.

Interestingly enough, both Braff and Schuyler are writing their next books in libraries.

BOOKED BY BOOK GROUPS

Panelists:

Shortly after a skirmish with the Paul Reubens Day crowd, I returned to the air conditioned somnolence of the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts for the final panel of the day. Ms. Benson was a very prepared moderator — perhaps overly so. She spent most of the panel reading notes and questions from various papers and seemed befuddled when she had to speak extemporaneously or repeat a question.

Heidi Benson tells the Booked by Book Groups panel that they have been Super-Glued to their seats to ensure that the panelists will not leave. The glue wore off in exactly 45 minutes.

|

This panel dealt specifically with the issue of how authors approached book clubs, but before this discussion started, some background was let loose.

Manfredi said that her book, Above the Thunder, was inspired by an article she read in the Cincinnati Inquirer about a ten year old girl who had thrown herself in front of a train after her mother had died of AIDS. She had wanted to be an angel. This story stuck with Manfredi for ten years and she then wrote the book. Word of her book had spread mainly through hand-sold copies at A Clean, Well-Lighted Place for Books. She then decided to talk with book clubs. She remarked that the book club caviar and champagne were motivating factors.

Brennert, whose work I know mainly from the 1980s incarnation of The Twilight Zone, said that he had left his heart in Hawaii over the years. Despite residing in Los Angeles, he had taken many trips to Hawaii over the years, he realized that nobody had written about 19th century Hawaii over the years. Amazingly, his story proved resilient to readers. The paperbck version of Moloka’I is now in its fifth printing. Brennert said that he had never been a member of a book club because he’s a slow reader and he likes to “bop around from subject to subject,” but he was grateful that they existed, rather than video game discussion clubs that discussed the subtext of Grand Theft Auto.

Fowler’s The Jane Austen Book Club came about from a sign that she saw at the Book Passage. She believed that a book existed with the name “The Jane Austen Book Club” and saw, to her dismay, that it didn’t. Thus, she wrote the book. But while there was an audience for Jane Austen, she didn’t realize that the bigger commercial factor in her title was “book club.”

Fowler says that she’s jealous of writers who claim that their characters write their books. “My charactersr are never that helpful,” she revealed. Fowler has been in touch with many book clubs since Jane Austen was published, including a club that has endured for 77 years by mothers handing down duties to their daughters (but, interestingly enough, not to their sons). Both Fowler and Brennert attributed the rise in popularity to Oprah. And she too noted the fantastic food. Fowler said that in one of her book clubs, a discussion of Richard Russo’s Empire Falls ended in tears. One of the problems of discussion, Fowler said, is that a person defending a book is less strong than a person attacking the book.

Brennert revealed that he had written three book club questions for his book.

Manfredi noted that a woman in Germany was writing a doctoral thesis. This student calls occasionally, but Manfredi confessed that she often makes answers up.

Fowler said that she’d rank an all-male book club “with a Bigfoot sighting.” She expressed a concern that she had seen that men might dominate the conversation. But she was aware of a book club-cum-poker game that men she knew had arranged. (One of them had chosen The Jane Austen Book Club deliberately just to get other men groaning.)

This particular panel was better than the Life Experiences panel. But perhaps realling the constricted and inorganic feel from my last venture inside the air conditioned theatre, I felt that there was something being lost in the discussion, which was starting to grow too sedated for my tastes. So I asked a twofold question: (1) What did these authors really feel about the inane book club questions in the back of their books, given that these lead to repetitive tropes and homogenized groupthink among people discussing the book? (2) In light of the resistance voiced on the panel, do authors really have much to say outside of the novel?

All of the authors hesitated for several seconds. They had not expected this. In fact, when answering my question, Brennert (unlike Fowler and Manfredi) wouldn’t even look me in the eye. But Brennert, to his credit, didn’t try to evade the issue (unlike the other two). He suggested that with Moloka’I at least, the story had been so meticulously researched that he felt obligated to pen the afterword. This still didn’t address the fact that Brennert had penned the book club questions.

At this point, Benson looking at her watch, wrapped up the panel precisely at 3:30 PM.

CONCLUSIONS:

Overall, I enjoyed my Books at the Bay experience. It was good to chitchat with many of my favorite indie booksellers. I even ran into David Kipen twice, who I had not known would be interviewing Gus Lee. He did tell me that a podcast would be available through the Chronicle site.

I’d say the panels themselves worked when everything was laidback and loose, they failed abysmally when they were formal and restricted. Books by the Bay, I’m convinced, belongs outside in the sunshine (or the fog) rather than in some antiseptic theatre with antiseptic moderators. It also needs harder questions thrown into the mix or else the panel itself is a pretty pointless (and nearly lifeless) experience.

[UPDATE: An additional account can be found at Ghost Word.]

[UPDATE 2: The one and only Michelle Richmond has another account over at the Happy Booker.]

Years later, in 2001, while teaching at Indiana University, Ames was asked to blurb a transexual memoir from Temple University Press. He read The Woman I Was Not Born to Be by Aleshia Brevard, a book by a 1950s drag queen. Brevard was the first Marilyn Monroe impersonator. She eventually had a sex change operation and became a B-movie starlet.

Years later, in 2001, while teaching at Indiana University, Ames was asked to blurb a transexual memoir from Temple University Press. He read The Woman I Was Not Born to Be by Aleshia Brevard, a book by a 1950s drag queen. Brevard was the first Marilyn Monroe impersonator. She eventually had a sex change operation and became a B-movie starlet.