While the majority of the American moviegoing public took in family fare like Enchanted, our humble party was compelled to check out Frank Darabont’s adaptation of The Mist. We figured that Darabont would once again mine Stephen King’s humanism for benign and competent cinematic fare — a la Shawshank and The Green Mile — and that all this would once again make us feel relatively sanguine about the human spirit. How wonderfully wrong we were!

What we experienced instead was an unexpectedly feral allegory of post-9/11 America set, like Dawn of the Dead, in a consumerist center (no accident perhaps that it’s one of those supermarkets with a late-1970’s aesthetic) and once again reminding us that the horror genre, by way of its speculative format, may be more capable in revealing truths about the human condition than some of the forthcoming squeaky-clean Oscar contenders. There were vicious tendrils, giant monsters that dwarfed even my imagination when I read “The Mist” years ago as a teenager, fundamentalist nuts, graphic lacerations, and one of the most brutal finales I’ve seen in a Hollywood horror film in quite some time. That such a brass-balls flick came not from the capably savage hands of Eli Roth or Guillermo del Toro, but from the warm-hearted Frank Darabont — never particularly known for his gore — was especially admirable. If the intensity wasn’t on the level of Cronenberg or Argento, The Mist put The Majestic, that naive and dreadful stab at the Capraesque, well out of my mind. As the body count continued to tally up, as good people were killed (including children!), and as King’s novella was wryly recontextualized for our terrifying modern age, I couldn’t help but wonder if the violence had been coaxed out of Darabont by executive producer Harvey Weinstein, who told Darabont that if he did not go the distance, he was a coward.

Whatever the circumstances, The Mist may very well be one of the most quietly subversive movies of the year. Roger Ebert is wrong to pooh-pooh the absurd storyline. The explanation for the titular fog is as convincing as a bad pulp tale from the 1940s, but this is not why one watches this movie. Aside from his usual stock character actors (including William Sadler), Darabont has, for the most part, cast second-tier actors who are not so easily identified. There isn’t a big name actor here to distract us from Darabont’s inverted take on populism. The movie is, instead, a portrait of Americans who want to be good and kind to each other, but who remain incapable of such basic decency without material comforts. Respect for other differences, however loathsome, are the first to go when presented with a terrifying threat and when the true nature of military conquest is revealed. And consider the way in which the audience’s expectations are tampered with. Darabont, knowing full well that the audience is screaming “Get the fuck out!” at the top of their lungs (the audience I saw this with certainly did), keeps his characters lingering in ghastly scenarios about twenty seconds longer than the audience expects them to leave. This is cheap but effective suspense, but it has the added symbolic value of revealing a slow and stigmatized America incapable of reacting smartly to trauma. There is also the manner in which one of the main human antagonists is disposed of. Yes, we’re all cheering the death. (Indeed, each gunshot was cheered on by the audience, myself included.) But in doing so, I couldn’t help but feel that I was proving Darabont’s point. Watching this flick, we think that we’re civilized by way of being removed from the fantastic environment. But I felt deeply ashamed at celebrating the slaughter. However execrable the character, is this not the same savage instinct that we’re seeing portrayed on the screen? In light of the casual manner in which a television audience applauds Kiefer Sutherland willfully breaking the Geneva Convention in waterboarding a suspect, Darabont’s clear awareness of the audience here is striking.

Whatever the circumstances, The Mist may very well be one of the most quietly subversive movies of the year. Roger Ebert is wrong to pooh-pooh the absurd storyline. The explanation for the titular fog is as convincing as a bad pulp tale from the 1940s, but this is not why one watches this movie. Aside from his usual stock character actors (including William Sadler), Darabont has, for the most part, cast second-tier actors who are not so easily identified. There isn’t a big name actor here to distract us from Darabont’s inverted take on populism. The movie is, instead, a portrait of Americans who want to be good and kind to each other, but who remain incapable of such basic decency without material comforts. Respect for other differences, however loathsome, are the first to go when presented with a terrifying threat and when the true nature of military conquest is revealed. And consider the way in which the audience’s expectations are tampered with. Darabont, knowing full well that the audience is screaming “Get the fuck out!” at the top of their lungs (the audience I saw this with certainly did), keeps his characters lingering in ghastly scenarios about twenty seconds longer than the audience expects them to leave. This is cheap but effective suspense, but it has the added symbolic value of revealing a slow and stigmatized America incapable of reacting smartly to trauma. There is also the manner in which one of the main human antagonists is disposed of. Yes, we’re all cheering the death. (Indeed, each gunshot was cheered on by the audience, myself included.) But in doing so, I couldn’t help but feel that I was proving Darabont’s point. Watching this flick, we think that we’re civilized by way of being removed from the fantastic environment. But I felt deeply ashamed at celebrating the slaughter. However execrable the character, is this not the same savage instinct that we’re seeing portrayed on the screen? In light of the casual manner in which a television audience applauds Kiefer Sutherland willfully breaking the Geneva Convention in waterboarding a suspect, Darabont’s clear awareness of the audience here is striking.

The Mist is a major step forward for Darabont. In addition to finding his cojones, Darabont, known for his static shots, has not only shifted his cinematography to a more shaky Battle of Algiers milieu, but his camera frequently zooms in on the people, suggesting that we’re incapable of examining our own inadequacies. The enemy, it would appear, is us. Sure, it’s ultimately something of a replay of the Twilight Zone episode, “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street,” but Darabont has injected some class prejudice. (I particularly liked how the attorney character was African-American and how he’s the one to call the others “hicks.”)

He’s also merged an old-fashioned sensibility with a carnal and contemporary one. Aside from his decision to go ten more intense steps beyond the novella’s finale, he is also, at times, resolutely faithful to the text, even reproducing some of King’s more ludicrous dialogue (“There’s something in the mist!”). The tentacle does indeed smash a bag of dog chow upon its first appearance. This was one of the more absurd touches in King’s novella, but in Darabont’s hands, it manages to work, in large part because Darabont has made the tentacle a large and imposing thing that will rip out your guts in seconds.

I was also impressed by the attention to the mist monster ecosystem. Large and beautiful insects affix themselves to the supermarket window, attracted to the glass the way that moths flock to light, only to be snapped up ruthlessly by gargantuan winged beasts. Nothing here is quite what we expect, which is saying a good deal in light of the fact that the story is essentially a familiar one.

I was also impressed by the attention to the mist monster ecosystem. Large and beautiful insects affix themselves to the supermarket window, attracted to the glass the way that moths flock to light, only to be snapped up ruthlessly by gargantuan winged beasts. Nothing here is quite what we expect, which is saying a good deal in light of the fact that the story is essentially a familiar one.

Perhaps I’m particularly crazy about The Mist because it doesn’t pretend to be anything it’s not. Frankly, I’ve seen a lot of bullshit at the movies this year. But The Mist is an old-fashioned horror movie, eliciting convincing performances from most of the cast. But, most importantly, it’s a movie in which the acting and the atmosphere is prioritized over the effects. As Hollywood attempts to extract twelve dollars from your wallet for movies that are nothing more than style over substance, I find it amazing that it’s come to B-movies like The Mist instead of well-intentioned misfires like Rendition to get us to feel frightened and all too aware of contemporary horrors. Sincerity, it seems, has become a groundbreaking commodity in the cinema.

I will have more to say at length about Winsor McCay and, specifically, Checker Publishing’s reissue of The Dream of the Rarebit Fiend later. For now, I direct you to

I will have more to say at length about Winsor McCay and, specifically, Checker Publishing’s reissue of The Dream of the Rarebit Fiend later. For now, I direct you to

Whatever the circumstances, The Mist may very well be one of the most quietly subversive movies of the year.

Whatever the circumstances, The Mist may very well be one of the most quietly subversive movies of the year.  I was also impressed by the attention to the mist monster ecosystem. Large and beautiful insects affix themselves to the supermarket window, attracted to the glass the way that moths flock to light, only to be snapped up ruthlessly by gargantuan winged beasts. Nothing here is quite what we expect, which is saying a good deal in light of the fact that the story is essentially a familiar one.

I was also impressed by the attention to the mist monster ecosystem. Large and beautiful insects affix themselves to the supermarket window, attracted to the glass the way that moths flock to light, only to be snapped up ruthlessly by gargantuan winged beasts. Nothing here is quite what we expect, which is saying a good deal in light of the fact that the story is essentially a familiar one. Have a fantastic Thanksgiving. If you’re on KP duty, take deep breaths and realize that there is an end in sight and that the guests you are hosting will be especially appreciative of your efforts. If the immense intake of food is overwhelming, take deep breaths and realize that the postprandial floor plop is likewise an end of sorts — the kind of physical maneuver that offers an entirely unexpected form of gratitude and that doesn’t even involve a deity. And if the five pounds you’ve gained is enough to make you shed more tears than a casual viewing of Terms of Endearment, reject the consumerist impulses on Friday and go for a long walk instead.

Have a fantastic Thanksgiving. If you’re on KP duty, take deep breaths and realize that there is an end in sight and that the guests you are hosting will be especially appreciative of your efforts. If the immense intake of food is overwhelming, take deep breaths and realize that the postprandial floor plop is likewise an end of sorts — the kind of physical maneuver that offers an entirely unexpected form of gratitude and that doesn’t even involve a deity. And if the five pounds you’ve gained is enough to make you shed more tears than a casual viewing of Terms of Endearment, reject the consumerist impulses on Friday and go for a long walk instead.  A true activist stands by his principles. For the record, a few major publishers have offered me considerable money to advertise on Segundo, with the proviso that I only interview their authors. One even suggested that I could download leftover audio snippets of authors from their digital archive and I could edit my questions in. I found this to be quite unsavory, and I politely declined these offers.

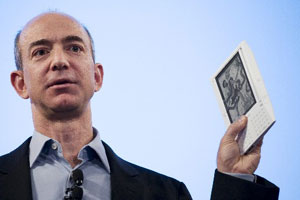

A true activist stands by his principles. For the record, a few major publishers have offered me considerable money to advertise on Segundo, with the proviso that I only interview their authors. One even suggested that I could download leftover audio snippets of authors from their digital archive and I could edit my questions in. I found this to be quite unsavory, and I politely declined these offers.  Howard Rheingold, the man behind

Howard Rheingold, the man behind  As

As