The boys over at Media Sound Off have an interesting concept for a podcast: interview the interviewers and the other strange souls who toil in this goddam media landscape. Well, they’ve interviewed Jesse Thorn and they’ve interviewed me. The former makes sense; the latter baffles me. I haven’t yet listened to either show, but if I had to recommend one without listening, I’d choose Thorn, if only because I suspect his signature is far more concise on paper.

Month / October 2008

Example #453 of the Radio Industry’s Failings

Sweet Jesus. For goodness’s sake, program directors, why do you continue to syndicate idiots like Bob Grant when there are some of us out here who actually conduct more than a modicum of research before spouting off in front of a mike?

Well, A Good Polka It Is For My Good Friend Lee Siegel

Nathan Burke once said, “Get out of the freight car or I’ll kick your bitchy little ass, Mr. Siegel,” and for Adam Bellow whiny little essays like this one were considered “the spoils of nepotism.” Kafka once asked Max Brod to burn his writing, fearing that a shrimpy little weasel named Lee Siegel would quote him in a century. (What a mess that would make.) We know now thanks to Lee Siegel that you can turn in the world’s most incomprehensibly idiotic essay and still collect a paycheck from the New York Times Book Review. A modest question arises, however: If Lee Siegel is such a legend in his own mind, why is it that his ego continues to be fed by the Gray Lady? When Lee Siegel bangs like an autistic monkey on his keyboard, you’re in big trouble. I mean, big trouble.

Let’s start with a couple of harmless tests. If you’ve read Siegel’s essay and didn’t want to stab yourself after the first paragraph, did you want to stab yourself after the second? First, try to wonder why Siegel feels the need to name-drop six literary names in the first paragraph. Don’t worry, I couldn’t tell you either. Could it be that Siegel has nothing interesting to say about anything? Once you recover this primal state of being after getting past the second paragraph, Siegel tells us, you will then take off your brassiere or your boxers for Mr. Siegel. You will hand him your credit card and he will spend the entire day maxing it out, ruining your hard-earned credit with a spate of 1-900 calls. Volunteers?

Now, I never swallowed when Siegel asked. Nor did I suck him off at any point. Lee Siegel’s downfall was his Dubya-like insistence that he was right, that he was funny, and that he had some scintilla of talent. His undoing arrived — well, how many undoings were there really? The cowardly sock puppet at the New Republic? The tendency to hold any panel or discussion hostage? The inability to act or think like a grown-up?

Well, enough of Lee Siegel. And enough with this parody. My girlfriend pointed me to the article, knowing damn well that I would want to kick this sad sack of a man when he’s down. So let us conclude this entry by pointing out the obvious fact: if Bruno Kirby were still alive, he’d play the role of Lee Siegel in the inevitable movie.

Dave Itzkoff: The Sarah Palin of Science Fiction

Neal Stephenson? You betcha!

State of Affairs

All energies are currently reserved for this deadline. I have made the assignment a bit more difficult than it needed to be. But that’s what happens when you hire me. I am not the type to tackle an assignment in any formulaic way. It must be fun. It must involve honest labor. If it does not crackle in some sense, then it’s not worth doing. But a fillip spills over to this blog, just as it always does, creating another entry that is not so much about blogging, as it is about why I am not blogging. (It is because people are paying me not to blog, or rather to devote my energies elsewhere. But this seems to be the end of these enjoyable professional endeavors for now. But I hustle, hoping to find more.)

Others might posit a simple explanation, confining the reason to a single sentence. Normal people certainly would. I was recently identified as an “acclaimed writer” in a press release, although I have yet to win an award aside from the Cracker Jack prize that is, thankfully, available to any dutiful bodega customer, and I certainly have no time right now to work on my fiction, which saddens me a bit. (A writer with a bountiful financial cushion recently complained to me that he had to spend a whole week coming up with an idea. I wonder if he truly loves his art. I certainly do, and have more ideas than time available.) But, on the whole, I remain sanguine and pro-active. The general state of affairs involves something that happens when you spend most of your time hustling. I assure you that I am merely a man trying to get by on intellectual labor. It is certainly not easy right now. And I’m far from alone. Every good and talented soul I know is hurting — including those who are better than me.

Much of this has caused me to reconsider just what I’m doing. Very few people cared about the New York Film Festival, and certainly none of the outlets I pitched were hep to the idea of detailed coverage. So I felt compelled to atone for this inadequacy, doing what I do. And this is increasingly becoming the justification for why I devote much of my energies to this site: because nobody else is doing it. Because nobody wants to do it. Nobody is willing to throw money at the arts anymore. I’m happy to carry on doing it. The landlord, however, requires rent. This is why I have spent a good deal of time scrambling for a way to make this place — Segundo and the lot — self-sustaining. I’ve even managed to get a number of potential sponsors to talk with me. 2009, they say, that’s when we’ll go with your plan.

But there are two and a half months left in 2008. Thus, the dilemma.

So, for the moment, I have frozen production on The Bat Segundo Show for 2008. For how long, I do not know. Could be weeks, could be months, could give it up completely. There are still many interviews in the can, and a few interviews I’ve yet to conduct. So it doesn’t mean that the show itself won’t continue to pump out installments. All told, we’ll probably get to Show #250 by the end of the year. (And for the record, I could easily do a hundred more of these shows and still have fun with this.)

I won’t ask for money. I don’t want to abuse this idea too much. We tried the pledge drive, fell short of the goal, and I tried to keep the thing going on my own dime as long as I could. Thanks to all those who kindly contributed. It helped more than you know. If Segundo is to carry on, I’m going to have to lock sponsorship into place. There have been talks. There has been some interest, but fish don’t wish to bite until next year. Presumably knowing the precise guy will sit in the White House next year is the bait they’re waiting for.

So that’s where we’re at. Don’t worry. I haven’t given up, but I’m trying to survive right now. So if things are sporadic or piecemeal here, well, you now know why.

A Hatchet and a Scalpel!

Late Bloomers and Early Risers

This Malcolm Gladwell article is quite interesting, if only for the wry way in which Gladwell suggests that Jonathan Safran Foer’s best years are behind him. One thing Gladwell does not seem to account for is the writer’s need to support himself with other types of writing that are more lucrative than fiction, because the writer does not wish to answer the dunning rap of a landlord. With rare exceptions, the landlord will not accept the perfectly reasonable explanation that the writer is, indeed, a late bloomer or a verbal toiler of some sort. Nor will the American government appropriate the appropriate bailout funds for citizens who fit this description. (via Mark Athitakis)

National Book Award Finalists Announced

Now this is a very intriguing list.

Fiction

Aleksandar Hemon, The Lazarus Project (Riverhead)

Rachel Kushner, Telex from Cuba (Scribner)

Peter Matthiessen, Shadow Country (Modern Library)

Marilynne Robinson, Home (Farrar, Straus & Giroux)

Salvatore Scibona, The End (Graywolf Press)

Nonfiction

Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (Alfred A. Knopf)

Annette Gordon-Reed, The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family (W.W. Norton & Company)

Jane Mayer, The Dark Side: The Inside Story of How the War on Terror Turned into a War on American Ideals (Doubleday)

Jim Sheeler, Final Salute: A Story of Unfinished Lives (Penguin)

Joan Wickersham, The Suicide Index: Putting My Father’s Death in Order (Harcourt)

Poetry

Frank Bidart, Watching the Spring Festival (Farrar, Straus & Giroux)

Mark Doty, Fire to Fire: New and Collected Poems (HarperCollins)

Reginald Gibbons, Creatures of a Day (Louisiana State University Press)

Richard Howard, Without Saying (Turtle Point Press)

Patricia Smith, Blood Dazzler (Coffee House Press)

Young People’s Literature

Laurie Halse Anderson, Chains (Simon & Schuster)

Kathi Appelt, The Underneath (Atheneum)

Judy Blundell, What I Saw and How I Lied (Scholastic)

E. Lockhart, The Disreputable History of Frankie Landau-Banks (Hyperion)

Tim Tharp, The Spectacular Now (Alfred A. Knopf)

Deadline

Barring any necessary coverage of the impending apocalypse (or minor distractions), I am stepping away from this website for a few days to be a good monkey and meet a looming deadline. Which is also why I have been sporadically answering emails. All is well. But all is busy. More soon. Many very cool things are coming up the pipeline in terms of podcasts and long-form content. Here’s a hint for one of the forthcoming podcasts:

And the Booker Goes to…

Roundup

- Okay, a considerable number of obligations preclude me from lengthy posts over the next few days. But once I get over the hump, there will be a considerable amount of content here. Bear with me. In the meantime, here are a few short blips.

- Clive James’s “The Book of My Enemy Has Been Remaindered.”

- I was in a Midtown diner yesterday and I overheard two young gentlemen, both low-level workers in a financial firm sitting at an adjacent table, remark that “the Nobel’s currency has plummeted” in response to the news that Paul Krugman had won the prize for Economics. It is worth noting that these two gentlemen assured each other in desperation that they understood what the current Dow Jones yo-yo meant. And my dining companion and I, who were discussing the Literature and Peace prizes, were highly amused when they failed to offer an explanation for this apparent confidence and understanding, and the two gentlemen, in turn, began to cadge from our conversation when they ran out of conversational topics.

- If you genuinely believe that USA Today represents a legitimate outlet for books, consider its current books page. The two top stories involve Tony Curtis and Maureen McCormick, making this purported “books section” no less different from People Magazine. This, I presume, is the wave of the present.

- It appears that Milan Kundera is now in the process of being denounced. Orthofer has more, but I’m wondering if anyone will have the bravery to declare how overrated this Czech writer is.

- Tod Goldberg on Lawrence Shainberg’s Crust.

- Finally, when you’re a VP candidate who can’t even get support at a hockey game (complete with thundering music attempting to drown out the boos), chances are that your campaign is pretty close to finished.

NYTBR: Polishing the Rails

News emerged over the weekend that Dwight Garner was fleeing the New York Times Book Review for a gig as a daily books critic. With Rachel Donadio leaving the Book Review in the summer and Sam Tanenhaus performing double duty as editor of NYTBR and Week in Review, one wonders just who actually is running the NYTBR these days. Sure, Gregory Cowles was just bumped up to preview editor in September. But with the deputy editor slot open, does this mean Cowles will get two promotions in two months? Or will this slot go another editor over there?

One can only hope that all this staff shuffling reflects the beginnings of a much-needed regime change at the NYTBR. The NYTBR has become an out-of-touch, calcified rag in which it now takes two months after pub date for a major review to run, no-nothing dunces like Dave Itzkoff review science fiction, vaguely quirky writing (in the books reviewed or the reviews itself) is actively discouraged, translated fiction is regularly limited, and the editors actually believe that Henry Alford is funny. Compare any issue of the NYTBR under the Tanenhaus-Garner run against any issue under any issue edited by John Leonard, and you will see just how far this once-important section has fallen.

And as the Observer‘s Leon Neyfakh reported today, there was a time not long ago in which Dwight Garner felt the same way. Today, Garner has changed his tune, pointing out that “it’s a piece that clings to me on Google like a vampire bat.”

Is that Garner’s wry way of telling us that he’s in dire need of a blood transfusion? That he’s washed up? That he, just as he predicted twelve years ago, is incapable of regularly throwing sparks? Sounds very much like business as usual. In other words, why buy Valium when Garner is there in the daily?

New Roundup

One of my projects over the past few months was reading somewhere in the area of sixteen books (along with a good deal of beginnings) for a science fiction roundup. I’m pleased to report that the fruit of my labors can be read this Sunday at The Washington Post, where the books featured include Gene Wolfe’s An Evil Guest, Nancy Kress’s Dogs, Leslie What’s Crazy Love, and Benjamin Rosenbaum’s The Ant King. I did my best to include a variegated mix of big and small authors, expected and unexpected presses, et al. If I have erred even a quarter as badly as Dave Itzkoff, by all means, feel free to rip me a new one in the comments.

“My Friends”

Back in September, Paul Collins was ahead of the curve. Writing in Slate, Collins investigated McCain’s odd catchphrase, deployed quite liberally on Tuesday night during the second presidential debate. Collins tracked these mad dollops to William Jennings Bryan’s Cross of Gold speech from 1896. Bryan, as you may recall, died in his sleep five days after the Scopes Monkey Trial decision.

If McCain appears to be on the verge of losing this race, the least he can do is to consider the sponsorship opportunities. Let’s say that McCain were to replace “friends” with “space” and charge MySpace $50 for every unfurling of the phrase. Not only would McCain stand to make well over a grand from Tuesday’s appearance, but he would, at long last, demonstrate some familiarity with the Internet at the last minute. (Okay, so he’d be a little behind the curve here, because he’s not exactly aware of Facebook. But we expect some unfamiliarity with the social network of choice among our old geezers.)

Alternatively, I’d like to see John McCain sing “Why Can’t We Be Friends?” in answer to a question if he can’t come up with a cogent answer.

Market Watch

For those paying attention to the remarkable slide of the Dow Jones Industrial Average (10,766 last Friday and 8,635 today), which comes after a colossal amount of money was given to Fannie, Freddie, AIG, and certainly not you and me, there is thankfully one website you can check on until we reach the inevitable economic apocalypse — a period that may be referred to in the history books as The Greater Depression. Or perhaps The Greatest Depression on Earth!

I’m tempted to bet money on whether or not the market will collapse, but my currency may not be around long enough for me to claim my earnings.

Incidentally, we’ll be celebrating the 79th anniversary of the 1929 Wall Street Crash in a couple of weeks. And looking at the eerily similar graphs of that year, perhaps we’ll be “celebrating” in more ways than one. If there’s a bump next week, followed by a plummet, well then you can’t say that history doesn’t have a way of repeating itself.

And David Kipen refused to consider my Federal Writers Project idea.

New Review: Nick Harkaway

Today was quite a busy day. So I only just caught wind of this. But you can read my review of Nick Harkaway’s The Gone-Away World in today’s Barnes & Noble Review. The novel seems to have been strangely categorized as science fiction by the few American newspapers who have bothered to review it. But feel free to judge for yourself. Here’s the first paragraph of my review:

The Gone-Away World is a narrative cloudburst loaded with mordant dust devils whirling close to Iain M. Banks, a philosophical cumulus reminiscent of Neal Stephenson, and a bold downpour of mimes, gong fu, and other torrential tomfoolery. It is not, despite Nick Harkaway’s suggestive nom de plume, a svelte Jazz Age meditation on affluence and perception. But it does tackle these two conditions in a universe close to ours, one that involves Cuba joining the United Kingdom and the All Asian Investment and Progressive Banking Group standing in for the World Bank. Harkaway has written a first novel with an assured and clever voice, riddling his readers with brio and a few unusual thought experiments.

Rhymes with Judd Hirsch

It did not take long for American literary critics to rise to the bait. The real scandal of Adam Kirsch’s comments is not that they revealed a secret bias for insularity on the part of The Adam Kirsch Committee. It is that Adam Kirsch made official what has long been obvious to anyone paying attention: The Adam Kirsch Committee, composed of two members (Kirsch and his ego), has no clue or interest in genre or anything outside of recondite realist literature, no awareness of any writer taking real literary chances, a dismissive interest, at best, with books that challenge conventional notions, and an almost total inability to follow John Updike’s first rule of reviewing. Kirsch should respond not by imploring his editors to have him write more boring and lifeless reviews, but by seceding, once and for all, from the sham that American book reviewing has become.

It did not take long for American literary critics to rise to the bait. The real scandal of Adam Kirsch’s comments is not that they revealed a secret bias for insularity on the part of The Adam Kirsch Committee. It is that Adam Kirsch made official what has long been obvious to anyone paying attention: The Adam Kirsch Committee, composed of two members (Kirsch and his ego), has no clue or interest in genre or anything outside of recondite realist literature, no awareness of any writer taking real literary chances, a dismissive interest, at best, with books that challenge conventional notions, and an almost total inability to follow John Updike’s first rule of reviewing. Kirsch should respond not by imploring his editors to have him write more boring and lifeless reviews, but by seceding, once and for all, from the sham that American book reviewing has become.

When Kirsch accuses the American literary community of being raw and backward, and the Nobel committee from selecting writers who “fit all too comfortably on junior-high-school reading lists,” he is failing to live up to an inclusive enlightenment that goes back practically to the Revolutionary War. It was more than 200 years ago that Sydney Smith, the English wit (also a reverend), famously wrote in Elementary Sketches of Moral Philosophy: “Have the courage to be ignorant of a great number of things, in order to avoid the calamity of being ignorant of everything.” Not only does Mr. Kirsch lack that courage, but he fails to cite specifics on the fallacies of these “almost folk writers.” And he uses remarkable generalizations to suggest that these writers reflected the image of America that Europe wanted to see. On the contrary, Paris welcomed such radical American writers as Ernest Hemingway, Henry Miller, and James Baldwin into its fold. In 2001, Philip Roth won the Czech-based Franz Kafka Prize. Richard Powers, Donna Tartt, and Roth have all won the UK-based WH Smith Literary Award in the last decade. Indeed, the Right Livelihood Award — the so-called “alternative Nobel” — handed out an award to an American this year. To judge by these developments, you would think that Kirsch simply hasn’t been paying attention to the last ten years of American-European cultural relations.

But that, of course, is exactly the problem with Adam Kirsch. As long as the Nobel mess could still be mined for a straw man — as long as a sour critic like Kirsch had to leave the New York Sun for the online pastures of Slate in order to become a legend in his own mind — it was easy to make these generalizations and fall into the same trap as Horace Engdahl. And now that the Nobel Literature Prize has been handed out to Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clezio, and some Americans are scrambling to find out who he is, Kirsch can perform his happy little dance of how he knew this French writer all along.

I fully confess that I have not read a single word that Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clezio has written. I am ignorant, and am happy to fill in the gap. And I confess my ignorance here to avoid Kirsch’s greater calamity and his almost total absence of courage.

Roundup

- So the Nobel Prize goes to Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio — a writer who I’ve never read. And it’s all because I’m one of those thuggish American idiots who Engdahl is complaining about. Mr. Orthofer, as usual, has the goods here.

- I hope that I might atone for my unworldly nature by once again mentioning one of the best films that played the New York Film Festival, Tokyo Sonata. I assure you that my coverage of this movie is far from over. And I am pleased to report that the film now has an American distributor. It will be released by Regent in March 2009. I don’t yet know how many theaters it will play, but if it plays in your area, by all means catch it if you can.

- Bill Peschel, playing directly to my perverse nature, has kick-started a promising series: Great Moments in Literary Sex. Unfortunately, Mr. Peschel has yet to employ the gerunds “pounding” or “thrusting” in his posts. Let us hope for more Harlequin action in forthcoming installments.

- I must publicly denounce Random House for failing to send me books with bawdy covers. Oh well. Perhaps someone else will come through.

- The Wall Street Journal talks with David Lodge, and has me a bit sad that I lack the financial resources to travel to London to interview the man and conduct a proper conversation. (via Frank Wilson, who dutifully takes the WSJ on for getting the tone in Lodge’s oeuvre so fundamentally wrong)

- Also from Frank: A Hard Day’s Night in Yiddish.

- I got a tip on the new Pynchon novel a few weeks ago, but I was so busy with assignments and the New York Film Festival that I was unable to investigate. But thankfully, David Ulin has confirmed it with The Penguin Press.

- Mark Athitakis reminds us once again that there is more to Steinbeck than crowd-pleasing and ideological novels. I’m by no means a lover of all of Steinbeck’s work, but I’ve likewise never quite understood this rap. This is a nation in which writers are impugned if they get through to the masses, vilified if they don’t kiss the tastemakers’s asses, and celebrated if they abide by the take-no-chances boilerplate. There are exceptions to this, and certainly Steinbeck was an exception in his lifetime. But leave it to the next generation of closed-minded critics who would rather play predictable contrarians rather than attempt to parse books for what they are.

- And if people aren’t reading on the subway, then surely they can’t be reading in blue-collar Latino neighborhoods either! Daniel Mendelsohn is likely to pop his ignorant gaskets upon hearing this news.

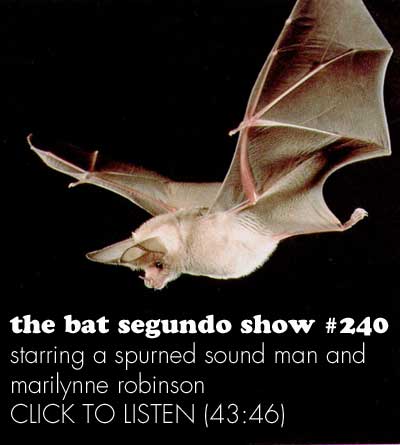

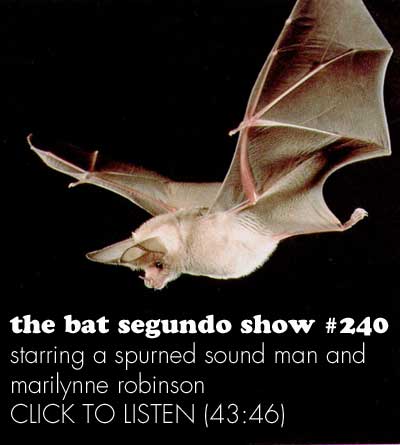

The Bat Segundo Show: Marilynne Robinson

Marilynne Robinson appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #240. Ms. Robinson is most recently the author of Home.

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Avoiding the relationship potential of malfunctioning XLR cables.

Author: Marilynne Robinson

Subjects Discussed: Revisiting the Gilead universe, Lawrence Durrell, Robinson’s aversion to sequels, the parable of the prodigal son, the role of letters and text within Gilead and Home, text as a lively and disturbing realm, affirming identity by chronicling detail, seizing the day, Bob Marley, the depiction of the home in Housekeeping in relation to the vertical landscape, “home” as a value-charged word, listening to vernacular hymns, characters who listen to the radio, music as the great common ground, music and memory, banishing certain words, whacking sentences down, characters and educational background, the advantages of not speaking, circular food in the Boughton household, the virtues of toast, family meals and communion, the frequency of dialogue in Robinson’s novels, the predestination colloquy in Gilead and Home, James Wood’s review, the advantage and limitations of third-person perspective, interpretation vs. living the events, the shifting definition of sin during the 20th century, Iowa and anti-miscegenation laws, the Chrysler DeSoto vs. Hernando De Soto, the Kennedys, secular figures within novels, Jonathan Edwards, hypocrisy and religion, the origins of character names, the role of judgment within family, Das Kapital and Jack’s Marxism, the history of The Nation, the writer-reader relationship, using a BlackBerry, and parody and the contemporary novel.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: I wanted to ask you about the tale of the prodigal son, which of course comes from Luke 15:11. The onus of guilt in that parable, however, falls largely on the son. Specifically, the quote is “Father I have sinned against heaven, and before thee / And am no more worthy to be called they son; make me as one of thy hired servants.” But Jack, he calls his father “Sir.” Not “Dad.” Although there’s a slight discrepancy near the end. He works on the DeSoto of his own accord. He’s often summoned to play on the piano and the like, and also work in the garden. But he’s sometimes an unapologetic sinner. And other times, he drowns his sorrows in alcohol. So the interesting question here about the prodigal son is: The framework of the Scriptures is clearly there in this book, but I’m curious as to when you decided to launch away from that. Likewise, was this actually a starting point? Or was it an intuitive process of trying to obvert what we know about that particular story from Luke?

Correspondent: I wanted to ask you about the tale of the prodigal son, which of course comes from Luke 15:11. The onus of guilt in that parable, however, falls largely on the son. Specifically, the quote is “Father I have sinned against heaven, and before thee / And am no more worthy to be called they son; make me as one of thy hired servants.” But Jack, he calls his father “Sir.” Not “Dad.” Although there’s a slight discrepancy near the end. He works on the DeSoto of his own accord. He’s often summoned to play on the piano and the like, and also work in the garden. But he’s sometimes an unapologetic sinner. And other times, he drowns his sorrows in alcohol. So the interesting question here about the prodigal son is: The framework of the Scriptures is clearly there in this book, but I’m curious as to when you decided to launch away from that. Likewise, was this actually a starting point? Or was it an intuitive process of trying to obvert what we know about that particular story from Luke?

Robinson: Well, I have a slightly different interpretation of that story than the one that’s generally circulated.

Correspondent: I think so. (laughs)

Robinson: You notice that the prodigal son says, “I am no longer worthy to be called thy son.” But from the father’s point of view, this is never an issue. He doesn’t ask for the son to satisfy any standards of his. He doesn’t ask for confession. He doesn’t ask for some plea for forgiveness. He sees his son coming from a distance and wants to meet him before he knows anything about him, except that he’s his son coming home. And I think that the point of the parable really is grace rather than forgiveness. The fact that the father is always the father. Despite and without conditions. And this is true in Boughton’s case. As far as he concerned, Jack is his son. And that’s the beginning and the end of it. Jack is not able to accept his father’s embrace.

Correspondent: It’s basically approaching a parable or a well-known story from a kind of cockeyed manner. Really, it comes down to this notion of the text as Scripture. I think certainly in Gilead, that was the case. And in this case, you have them throwing away letters. You have, of course, the love letters that are thrown down the drain. The letters that Jack sends out, which come back RETURN TO SENDER. And of course, they’re schlepping off a number of magazines to Ames, who lives down the block. So this is very interesting to me. Whereas the first book dealt explicitly with this idea of text as this panacea for loneliness, this book deals with disseminating the text out to other people, or getting rid of text. Which is why I ask the question as to how this relates to Scripture. Is text really something for us to cling onto in this? Whether it be a book or whether it be the Bible? Whether it be religious or literary or what not, there are matters of interpretation in life that go well beyond text and well beyond the idea of fulfilling this need to cure loneliness.

Robinson: Well, I think of text — by the analogy to Scripture that you’re making — I think of it is as something that is lively and disturbing. Disruptive. I mean, for example, say that Ames’s best hopes are met and his son receives the voice of his father when his son is an adult, that would completely jar the sense of memory, the sense of proximity to another human person, and all kinds of things that we think we understand. The letters that come to Jack and the letters that don’t come to him — they’re central. They’re alive, even though they are profoundly problematic. And I think of, in a way, text and Scripture as active in that way. As a sort of eccentric presence in human experience.

BSS #240: Marilynne Robinson (Download MP3)

Wrapping Things Up

Okay, folks, after about seventeen or so films (and manifold shorts) in two weeks, I’m officially finished with the New York Film Festival. I have seen two films devoid of dialogue (save a handful of lines). I have seen a ten-minute long take of a sheep giving birth. I have watched actors lose considerable weight for the sake of their art. I have witnessed Jonathan Rosenbaum’s eloquence stand out on an overcrowded panel. And I’ve written close to 15,000 words on all this.

So I think it’s safe to say that I’ve fulfilled my obligations to world cinema, that I’ve been a “good” cultural reporter. But I am now in need of a messy grindhouse flick and some bourbon to stabilize the artsy images and subtitles I have taken in during the last two weeks. The situation has become so severe that I am now having strange dreams with subtitles. I think that’s a sign that I’ve had enough world cinema for now. Which is not to say that I won’t be crawling back to the artsy IV drip in a few weeks.

There are a few more interviews and a few more reviews forthcoming pertaining to the New York Film Festival. But I should be shifting back to literary matters, as well as delving into a few other subjects. Thanks to all for participating in this crazed journalistic experiment! We march ever onwards!

McCain’s Economic Plan from Outer Space

Unanticipated Communiques from 2000

I have learned through Rachel Sklar via Twitter that Google, celebrating its 10th anniversary of collecting private data from individuals to sell advertising, has permitted users to search through the Google index as it existed in 2001. I performed numerous search experiments on several fascinating names and terms, revealing fascinating results, before turning the algorithm on myself, where several frightening emails that I had sent to my longtime pal, Tom Working, were uncovered. There was a specific purpose to “Jimmy.” But revealing this purpose causes one to lose sight of the interpretive possibilities within these deranged e-epistles. So here they are:

Date: Tuesday, September 5, 2000

Subject: enter “the Wolfe”Dear Mr. Working,

Dawn Wells has expressed disapproval at being associated with such a subversive cadre. This has not stopped her from being trapped on the island with the other Survivors. She’ll join our complex love menagerie and we’ll get in a carnal quintet before December. The ink is fresh and the paper is as disposable as a Joel Schumacher film.

Jimmy remains silent with the Washington office for three main reasons – (1) He is hard at work lobbying Congress to declare November 17 as a national holiday in his honor (this works in well with the production start date); (2) he was held up at the Smithsonian, mistaken for a rare elk species that resides in the Amazon jungle (and accidentally stuffed by several underpaid attendants); and (3) all he wanted was a Pepsi.

My safety is intact. I have lathered my body in baby seal oil and I have tested my flesh for flammability. Aside from burning my left eyebrow, I’m okay. And I anticipate applying the Zippo to my right eyebrow with the desired mixed results.

Which brings me to the issue of the Westcoast Six. I know that they’re into this whole comic book fanboy business. But their obsession with kryptonite has got to stop. I’ve called Marty Bernstein in Colorado and he’s flying in tomorrow with a lead box (codename – Pandora) that should settle the matter in a day. This should satisfy the money people for now.

How Jimmy will take this is anyone’s guess. I’ve been concerned that his pancreas will give out before the shoot. But I’ve ushered Jimmy into several free clinics for a second opinion. This is a tricky matter, given his traumatic experience in Washington.

And don’t worry about the Arizona market. We’re licensing Smell-O-Rama from John Waters for this production. Waters himself has expressed minor interest in the project. But he insists that we set the movie in Baltimore. I’ve convinced Waters that we will feature at least three shots of dogshit. He seems content with channeling Divine from the grave.

As you know, this represents considerable snowballing on my part.

“Wolfe” Habernathy sounds like a strong last-minute contender. I am, however, worried about his special requests. Six gallons of Vaseline every hour is a hard thing to come by. But if Habernathy wants it, I’ll just have to tell the Arizona and Colorado people that we just have to hang tough and provide it.

And I’ve got Ron Howard on board. He won’t be directing, but he’ll be appearing full frontal. Our test market scores indicate that a Jimmy-Ron Howard-Tipper Gore three-way will do extremely well in the Flagstaff market. Now I realize that this is an election year. But Tipper’s agent has expressed interest in becoming involved, if only to atone for the scathing censorship campaigning in the ’80’s. I’ve been perfectly honest about the circumstances. But who am I to argue? She wants to do it, if only to secure the smut bloc in Gore’s direction.

Bernstein, however, wants more. He talks deliriously of double-penetration. Can you ask the Wolfe just what kind of film we’re making here? Because the way Marty’s talking, I don’t think we’ll get the PG-13 rating.

I’ve taken care of the AOL problem. Steve Case wants a tie-in deal with the project and that should secure the capital. Never mind that the film takes place in the Middle Ages. But I have William Goldman busy doing rewrites and I’m sure we’ll figure something out.

Date: saturday, September 9, 2000

Subject: jimmy’s seen to that.Dear Mr. Working,

Well, it seems that we’ll have to recruit Ms. R. to inspire Jimmy to get in touch with his dog side. Since Jimmy seems to be fond of flagellation, I would suggest that he be repeatedly punched by her and conditioned to enjoy the fetishistic side of violence. We will keep Ms. R. at a distance and, for her protection, allow her to be in Jimmy’s presence for no more than ten minutes at a time, with several National Guard officers poised to shoot Jimmy’s kneecaps in the event that he gets “a little crazy”.

Ms. R. stands to make a killing off of this. The contract intends to split the profit as follows…

Publisher overhead 25 percent

Tom 20 percent

Ed 20 percent

Ms. R. 20 percent

Jimmy 3 percent

The SPCA 11 percent

Florence Henderson 1 percentI trust that you will agree that the deal is fair. And I wouldn’t worry about the literary angle. Joyce Carol Oates has been commissioned to write the review for the New York Times Book Review and she has expressed to me her admiration for Jimmy’s work.

The bodies, as you know, are a figment of Jimmy’s imagination. Jimmy would understand this, if only he had found a partner for his game of Tic Tac Toe. Sadly, the money people could not provide him with said partner.

Wink Martindale has expressed some interest in having Jimmy on as his first contestant for the new revival of Tic Tac Dough. But sadly, Wink wants to write the foreword of the book. He has tentatively titled his 2,000 word foreword – “I Never Understood My Adam’s Apple.” But sales reports indicate that we would lose 23 percent of the gross should this foreword be included. I’ve been on the phone with the Mark Goodson people trying to find another game show tie-in.

Date: Thursday, September 14 2000

Subject: a shocking developmentDear Mr. Working,

We here at the Walt Disney Corporation have recently learned of your plan (with your two associates, one Edward Champion and a man who is identified only as “Jimmy”) to cast one of our enduring characters, Mary Poppins, in a licentious light. We have also been informed of your attempts to contact Julie Andrews and involve her in this sordid offering.

Please be informed that we have muzzled Julie Andrews and provided her with all the penises that she could possibly desire for the next ten years. Accordingly, she has no interest in your project.

Concerning your use of our trademark character, I have one word to communicate to you – Stop.

While we admire your associative latitude with our creations (for they are, after all, OUR creations and not those of the overworked animators whose vocal chords have been conveniently cut), please understand that we will pursue your two-bit operation with every legal power we have under our wing.

However, your descent into porn comes at a time in which our corporation is considering pursuing similar markets, in much the same manner that we opened up our Touchstone film division to R-rated entertainment in the 1980’s.

Under the aegis of our newly created film division, Pound Politely Pictures, we would like to involve your associate, Jimmy, in Disney’s first multi-million dollar digital video porn feature. While we appreciate the input of you and Mr. Champion, we have come to realize that this Jimmy character is more sexually desirable to our demographic than the two of you put together.

In the spirit of compromise, we intend to throw loose women your way. Please keep in mind, however, that these women have serviced our lonely animators in the past and you may find that they malfunction upon climax.

Again, I request that you refrain from the “Mary Pophercherry” project and consider the benefits that our robots… er… women can offer you.

Thank you for your attention to this matter.

Sid Disney III

Executive InternP.S. Concerning the microwave, it is our hope that you can provide one.

NYFF: Waltz with Bashir (2008)

[This is the thirteenth part in an open series of reports from the New York Film Festival.]

About a week ago, fearing that all of the films were turning my mass into flabby mush, I walked two brisk miles in twenty minutes to take in Ari Folman’s Waltz with Bashir, my fourth film of the day. The movie had been described to me by one critic, who purportedly writes for a newspaper, as “a little fiesta” — a qualification that I certainly quibbled with at the time. I’m not sure that a movie depicting the trauma of war and memory can be accurately identified as a “little fiesta.” Certainly, the real-life figures drawn from the Israeli Army do interpret a break between battles as a “little fiesta,” even if they do not precisely use these two specific words. It is true that these soldiers toil in homemade banana leaf huts on the beach and frolic about just before their comrades get shot in their head. But to suggest that these activities represent a “little fiesta” is, I suspect, missing the point just a mite. I’d like to think that the critic in question was having me on, but when I questioned him about specific points in Israel’s history, he had no knowledge of events that went down in 1967.

A professional animator informed me that he had disliked the film because of its gimmick and what he characterized as “amateurish” animation, but this same gentleman had gone bananas over Shuga, a film that I did not care for very much. But it should be observed that the device of a journalist-like protagonist (here, Folman) who questions various people about the meaning of some hazy memory has its roots in Citizen Kane and numerous personal documentaries. I don’t think that Waltz with Bashir is a documentary exactly. It’s more of a recreated narrative with the appearance of an objective pursuit. Something akin to a memoir played out for the camera. Certainly the animation technique, of which more anon, lives up to this notion of reconstruction. If it is not technically successful, then it is certainly viscerally successful.

But I was determined to make up my own mind. My initial reaction after the screening was somewhat ecstatic. But now that it has been a week since I’ve seen Waltz with Bashir, I see the film with slightly different eyes. This is a film that stacks its deck just a bit too heavily. War is bad, and it doesn’t matter what side you’re on. But this predictable rush to condemn war leaves little for the audience to make up their own minds. Paths of Glory is one of the best antiwar films in cinema, but it was Kubrick’s visual genius and his insistence on wiggle room for the audience that made the film work. Waltz with Bashir offers no comparative anthill. It offers more of a sideways glance for a topic that requires thinking in twenty dimensions and more time than you have for rumination. (As Tom Bissell noted in his underrated memoir, The Father of All Things, Vietnam is a subject that one can easily devote a lifetime to.) Waltz is, however, very good about clarifying something just as troubling: more than two decades later, it cannot be stated with any certainty that war memories match up to the reality. (Come to think of it, this is likewise a subject broached by Bissell, and Waltz with Bashir and The Father of All Things might make an intriguing book/movie double bill, or perhaps “two little fiestas” for critics who cloak their ignorance in uninformed mirth.)

The reality itself is the 1982 Lebanon War, and Folman was directly involved. He fought in the Isreali Army and, now in middle age, he retains a memory of naked young men emerging out of the water before a ruined city. Some key friends figure into this fugue: the long-haired Carmi Cna’an, the teenager who everybody figured would succeed in any science, now living in Amsterdam and fiercely protective of his privacy; Shmuel Frenkel, who has taken up vigorous physical exercise and maintains a bald pate; and Israeli war correspondent Ron Ben-Yeshai, who telephoned then-Minister of Defense Ariel Sharon about the massacres at Sabra and Shatila and was given a peremptory answer to back off.

What is quite interesting about Waltz with Bashir is its production method. Folman tracked down the people who haunted his memories, interviewed them, and then styled an animated narrative around these efforts. He even managed to persuade these people to reproduce their voices for the film. (Only a handful of Folman’s subjects declined.)

Each figure appears flat, representing a clear demarcation along a particular focal point. At times, it’s akin to watching a Flash animation or something involving cardboard cutouts from a pre-digital time. Folman’s team has added layers of smoke and reflections atop this basic approach.

Folman also has respect for his subjects’ wishes. When Carmi Cna’an declares that Folman can draw him as he is talking about war, he requests that Folman not include his son. Sure enough, the camera drifts away from the house as Carmi Cna’an engages in this paternal pastime.

But while the testimony that Folman unravels from his subjects certainly inhabits a feel of a bygone time — an atmosphere enhanced by a decent soundtrack and dutiful pop cultural juxtaposition — Folman fumbles a bit on memory’s false starts. Folman’s best friend and shrink, Ori Sivan, brings up a psychological experiment. When subjects were given photographs containing one false element, they believed that the false element was part of the memory. While Folman has exonerated himself somewhat by presenting this caveat to those seeking truth, he nevertheless remains very determined to align his memories to the film’s final moment: a live-action video clip depicting Sabra and Shatila’s aftermath. And while this footage is heartbreaking, with injustices that made me quite angry, I’m not sure if it is entirely fair to corral the film’s theme of ever-shifting memory to this harder reality. If anything, this piecemeal clip presents additional questions about the relationship between documentation and memory that were better pursued in Standard Operating Procedure. This conclusive curveball not only undermines Folman’s thesis and stubs out the strengths of his early emphases, but I suspect that this eleventh-hour departure was why the critic offered me a diabolical conclusion about war being “a little fiesta.”

Take on Me — The Literal Version

If you somehow missed the original video, watch it first. (via MeFi)

See also The Family Guy version.

NYFF: The Headless Woman (2008)

[This is the twelfth part in an open series of reports from the New York Film Festival.]

Argentine filmmaker Lucrecia Martel — sadly one of the few women represented among the predominantly male auteurs in the New York Film Festival — doesn’t wish to spell out her entire scheme to the audience. She does have a crackling knack for presenting her muzzled puzzle from a subjective viewpoint. In The Headless Woman, Martel’s characters are often photographed from the passenger seat or the back of a car, suggesting that the audience is sitting right next to protagonist Vero, but helpless to intercede as this wealthy woman slips further down the drainage of her ethical predicament. Cinematographer Barbara Alverez confines the vista to medium shots, often static, with subjects in the background often fuzzing out in soft focus. From car windows, smiling motorcyclists pass and point to turn left while the air conditioning leaves those inside perspiring with a comfy gloom. When the camera opts for a long shot, Martel places her characters at extreme edges of the frame. One of Vero’s house workers discovers the remnants of a swimming pool or an old fountain paved over for Vero’s endlessly renovated garden. But there are no visible apples in this garden, presumably because privileged exoneration has made temptation unnecessary. Vero, you see, has driven over what may be a boy or a calf, reaching for her cell phone as the engine purrs on and rendered catatonic by this bump in the ontological road. Instead of stopping and living up to her moral responsibilities, she drives off, refusing to look back and suffering a severe emotional crisis that has her questioning her own powers of recall. We’re left to believe at film’s end that the incident may not have happened, but, by then, the dye in Vero’s hair has shifted from flaxen to black. Martel’s film represents the transformation; the accident is, quite literally, the calm before the storm.

Martel surrounds Vero with endless children who remind her of the crime. Martel makes Vero a dentist, and there is the suggestion here that Vero’s dutiful drilling upon these children’s teeth represents a full-bore assault on wisdom. After the accident, the tougher cavity jobs have been delegated to others. The mise en scene likewise deracinates the top physical features of characters. Vero is visually headless, framed by her own insularity. Vero is not heartless, for she breaks down in tears while attempting to wash her hands of the affair. The faucet malfunctions. She accepts the kindness of a concerned worker. Her head moves out of frame, revealing nothing more than her craned neck behind the partition separating Vero from the audience. We hear the baptismal rush of bottled water pouring down the top of her head. That the crime takes place on a road near a dry canal, filled by the weekend rainstorm precipitating the crime, suggests a theme of liquid replenishment. Vero is doted upon by help at the house, colleagues at work, and cannot even admire her husband in too-tight trunks. The crime, whether real or illusory, has revealed her true empty nature. “I killed someone on the road,” she states to anyone who will listen. But there is no proof, and this insinuates a deeper question of faith: an ethical stretch that is not quite religious spanning along a sinuous road leading to the annual “Smile Day,” where dentists investigate the porous ivory inside young mouths in the name of public service.

But the journey here is not entirely satisfying. Martel remains so determined to juxtapose Vero in a series of tapestries that match her internal despair that the audience does not have a choice but to go along. There is nobody here who truly scolds Vero for being so callous or unfeeling. There is nobody here who does not dote on her. We are left to witness a woman who, like Bartleby, would prefer not to. When police begin investigating details of the boy/calf’s death, we see Vero and those close to Vero craning their necks near the scene of the accident.

And while Martel injects some interesting subtext into her film, the story of a wealthy person who gets away with a crime has been done too many times before. One thinks quite naturally of The Strange Love of Martha Ivers, and it becomes apparent that Maria Onetto (who plays Vero) lacks Barbara Stanwyck’s eclat. This film could have used a Liz Scott-like side character to shake things up. But we do have an intriguing mother representing Vero’s logical development. This woman watches wedding videos from the past, barks at people to rewind moments because her memories are shot, and rattles off such unthinking “You were so beautiful. Why did you let yourself go?” to the snowy VHS bride, who is standing before her decades later.

Martel showed greater flair for depicting unexpected human behavior with The Holy Girl, which followed a religious teenage girl obsessed with a man who groped her on the street. But I suspect the absence of religion in The Headless Woman is one of the reasons why this film doesn’t quite work. Martel is a filmmaker who, like Pedro Almodovar, cannot make a secular film that packs the same punch. Religion is clearly in her blood. Had it likewise been in Vero’s blood, Martel would have had a hell of a movie.

What Are You Doing Here?

Screenwriters and storytellers, take note: With one simple question, Doctor Who was able to coax motivation out of a character faster than you could play a game of charades. A cheap trick perhaps in wanting your character to want you, but it works!

More obsession along these lines at Waxy.

(via Weekend Stubble)

Similiveritude

The scholar and the world! The endless strife,

The discord in the harmonies of life!

The love of learning, the sequestered nooks,

And all the sweet serenity of books;

The market-place, the eager love of gain,

Whose aim is vanity, and whose end is pain!

— Longfellow, “Morituri Salutamus”

There exists a maximum amount of prearranged information, cultural reconfiguration, and other artistic offerings that one can ingest before it becomes necessary to splash bracing water upon one’s face (or, to take this idea further, to permit dollops of grease to crease one’s cheeks because of a self-administered oil change in one’s figurative vehicle). This is where the frequently overlooked human experience comes into play. By venturing outside one’s domicile or spending time with other humans commonly referred to as “friends” (as they are specified in the parlance of our time), or by participating in intimate activities that involve getting out of the house because the windows have fogged up and nobody wants to talk about the pleasant musky odor known to cause roommates to scurry, one can encounter a new sheath of information or perhaps a sequence of events that is not as neatly contrived or as conveniently cross-referenced as the hallowed narrative construct. The real world is refreshingly anarchic and, depending upon your degree of involvement, can prove to be more interesting than the cultural item that purports to represent it.

It is for these reasons, among many, that books which cannot live up to life must be thrown across the room. It is for these reasons, among many, that one should strive to emerge beyond the house, speak on the phone, meet up for coffee with deranged but amicable individuals, chat up strangers, and otherwise own up to one’s responsibility to live, lest one takes the hypothetical hurling of the book across the room too seriously. (It is a mere parabolic flourish, but a pugilistic passion not to be entirely discounted!)

We speak of verisimilitude, but we don’t speak so often of its dreaded cousin, similiveritude. And if you don’t know what similiveritude is, it is not because I have coined the word. (As it so happens, I am not the originator. At the risk of adopting Googleveritude, another nonsense noun unfound through Googling, one encounters only two search terms for “similiveritude.” Some gentleman named Felix appears to be the first to bandy this about. So I’ll give Felix the proper plaudits — congrats, Felix! you were the one! can I have your baby? — and carry on with this febrile exegesis.)

You could very well be a simiiveritudinist, but you may not know it. And if you still don’t know what this word is, well, then you haven’t been paying attention to all the phonies and the charlatans laboring at “art” who refuse to admit that they have no real understanding of the world they live in, much less an emotional relationship to it. It is quite possible that they may capable practitioners of verisimilitudinous art, but this intuitive connection may very well be dwarfed by academia’s rotten institutional walls.

For the similiveritudinist, life must not only reflect art. Art is the very life itself! The similiveritudinist gravitates to an artistic representation in lieu of a stunning natural moment. He may attend an artistic function, hoping that it will fill in certain ontological vacuities from not thinking about or otherwise ignoring the world. The similiveritudinists talk with others, but the conversational topics are limited mostly to art. My empirical state has revealed that similiveritudinists are found in greater frequency in New York than in San Francisco. Similiveritudinists may be socially maladjusted, apolitical, asexual, or otherwise fond of keeping their noggins lodged inconsolably in the sand. Understand that there is no set formula here aside from highly specialized chatter. They may create callow games like “Name That Author” and they may put up photos on their websites of otherwise pleasant individuals who appear more bored than a silo stacked with accountants on the eve of the apocalypse. They may spend all their time occupying movie theaters — and I have seen more than a few etiolated souls who live for the New York Film Festival’s darkness over the past few weeks — but they cannot confess that they have enjoyed something, nor can they be authentic, stand apart, or otherwise inhabit the variegated identity within. They may indeed be employed primarily as critics, lacking the heart, the soul, the tenacity, or the talent to make a strike for the creative mother lode. The pursuit of art is, in the similiveritudinist’s mind, always a serious business. The worst of the similiveritudinists will thumb their noses at genre, popular art, or anything sufficiently “lower.” (This works, incidentally, both ways.) They believe that art, serving here as a surrogate plasma, must always be high, and that anything that falls beneath these cherished standards should be disregarded. They have perhaps inured themselves to the pleasures of a commonplace flagrance or the joys of a small child laughing as a sun sets over the playground. Joie de vivre? Try joie de livre! The similiveritudinist’s vivre, scant as it may be, is likely to be the hell of other people.

If you’re thinking that my wild ruminations here emerge in response to Horace Engdahl’s remarks concerning the current state of American literature, well, your hunch is partially correct. Michael Orthofer, a gentleman and a scholar, has already exoriated Mr. Engdahl quite nicely (as well as Adam Kirsch’s equally myopic remarks, which are perhaps a tad more pardonable because Mr. Kirsch is now out of a job and must now consort with the rabble, surviving hand-to-mouth like any other cultural freelance writer; which can’t be easy, because I suspect that many of us live more frugally and enthusiastically, and certainly less similiveritudinously, than Mr. Kirsch). So my specific reaction to Mr. Engdahl’s words isn’t quite necessary. Mr. Orthofer has already gone to town here. But I suspect that Mr. Engdahl and I might share a few grave concerns over the similiveritudinists who have invaded American literature. The crux of his criticisms suggest very highly that he may be an asshole, but he is thankfully not a similiveritudinist.

To live for culture is not enough. Culture is no replacement for the real thing. It is a helpful prism with which to find and divine certain meanings, but it is only one great piece of the living puzzle. And Mr. Engdahl is quite right to suggest that certain literary clusters within the United States have become too isolated and too insular. Did Jonathan Franzen read any other emerging author aside from the tepid name he picked from his middlebrow hat when he was asked to name his 5 Under 35 choice? We’ll never know, but his choice, which discounts the dozens of emerging voices who currently write for life and passion, is clearly that of a similiveritudinist. Likewise, David Remnick has been foolish enough to suggest that none of our celebrated writers are “ravaged by the horrors of Coca-Cola.” This is clearly the remark of a tony avocet too terrified to leave his golden perch. A casual saunter through any three city blocks reveals this ruddy symbol of the beast, the hellish mire of advertising that threatens to subsume all human moments. Has Remnick’s annual $1 million salary prevented him perhaps from, say, properly understanding what it is like to live under $30,000 a year? Or to work two jobs? Or to toil in the service sector?

If you do not know why you must tip a waiter in cash, but you can cite pitch-perfect passages from Milton, you are a similiveritudinist. If you do not know the price of a package of hamburger buns, but you’re not keeping track of how much you are blowing at Amazon, you are a similiveritudinist. If you have not skipped a meal so that another mouth can be fed, but you can describe the precise cordial to go along with a slice of pecan fig bourbon cake, you are a similiveritudinist.

Similiveritude represents everything that is wrong with American literature. Not all American literature falls under its terrible influence, and there are many literary advocates who understand its proper secondary place. To cure a similiveritudinist, you must ensure that this reader doesn’t just have a clue, but maintains an open and genuine curiosity about everything. To listen to a stranger because you are interested. To view the book as something that may be real in feeling but unreal in execution. To accept that something crazy, whether it be an elaborate series of footnotes or a moment of magical realism, is meant to happen in a book from time to time because the book is not real. More important than a critical scalpel hoping to be absolute in its appraisal is the idea of whether or not the book is applicable to the human heart, and whether or not this applicability feels intuitively true. From here, reasons and justifications can be loosened, with enough wiggle room to involve the reader.

Last month, Nigel Beale saw fit to tsk-tsk me because I had enjoyed a story involving an unhappy housewife having an affair with a 1,000-year-old woodpecker, and it had provoked an emotional reaction in me. It goes without saying that woodpeckers do not live this long and that most lonely housewives would settle for a Hitachi Magic Wand over a cuckolding canary. But the point here is that Mr. Beale, despite being a good egg, could not get beyond his own personal definitions of literature. And I fear that Mr. Beale might dip into the similiveritudinous deep end of the great literary pool because of his inability to (a) read the story to see what I’m talking about or (b) consider the story on its own terms, despite the unconventional sexuality presented. It is not a matter of Mr. Beale liking or disliking the story. That is his choice. But it is the instant dismissal of the story, and the dismissal of my reaction, that is the issue here. It would be no different if I were to dismiss a reader for, say, enjoying a James Patterson book. Now personally I loathe James Patterson’s work. But a reader has the right to have an informed reaction, even a positive one, and we have the obligation to listen to that reader’s reaction before chiming in with our own. Because there might be some intriguing personal reason for why someone prefers the story with the woodpecker or the James Patterson novel that represents a peculiar commitment to life.

Of course, abandoning similiveritude or listening to the other’s viewpoint doesn’t mean abandoning one’s artistic faculties. It merely means placing a particular way of living first: keeping an open mind and ensuring that the careful intake of culture remains a thorough but secondary occupation. What I am calling for here, quite optimistically, are more Renaissance men to inhabit a society in which there are no limits or barricades to one’s curiosity, a nation that counters charges of insularity with limitless interest, a country that can make Mr. Engdahl’s half-true claims utterly fallacious. It starts with the end of similiveritude. It continues with a series of upturned ears. It ends with an army of pro-active thinkers who value life first.

Gosh Golly, Godot

I am very honored to have been included in this quite important poetry collection. It appears, however, that Bat Segundo, responding in the For Godot comments, was none too happy about the controversial prosodic pilfering. What is perhaps funnier than the experiment itself is how so many egos have taken offense at this Situationist tomfoolery (more sustained horrific reactions can be found at The National Poetry Foundation blog). Danny Pitt Stoller writes:

If someone published an article containing false information about me, I would want it removed from the Web; it is no different for you to claim I wrote a certain poem when I did not. It is my basic right to protect my name and reputation, and I find it really tasteless that some people would laugh this off as some kind of avant-garde experiment.

It is worth observing that Danny Pitt Stoller’s name has been frequently used as a mark. Despite being married, Mr. Stoller has slept with a mere 2.2 people in the past eleven years, and hopes that he will yield 2.2 children in the next eleven years. He once ran for treasurer, losing to Esmerelda Muttmuffins by a 72-28 margin. Ms. Muttmuffins still holds the coveted position. There was a six month period in 1997 in which Mr. Stoller’s telephone bills were about $300 monthly, the result of too many 1-900 telephone calls. Mr. Stoller is a legally ordained minister and has officiated over many weddings. That woman who married a dolphin some years ago? It was Mr. Stoller who presided over the ceremony. Mr. Stoller has written 210 letters to the editor, but none of them have been published in Newsday. He wears pink socks in his bedroom, but never in public. He genuinely believes that Michael Bay is one of the most important film directors of our time, and has watched every episode of The Beverly Hillbillies twice.

And, yes, Mr. Stoller is dour and humorless. (Well, not quite dour and humorless. Contact with him in 2010 has revealed a sense of humor and elicited a slight modification to this entry.)

How About Her? Ehhhhhh? Now Get Off My Damn Lawn!

New Review: Thomas M. Disch

My review of Thomas M. Disch’s just-released short story collection, The Wall of America, appears in tomorrow’s Los Angeles Times, but appears to be available today. You can also listen to my podcast interview with the late, great Disch over here, which concerned Disch’s previous book, The Word of God.