Wayne Kramer has made two exceptional motion pictures. The Cooler presented us with the wild premise of a pathetic loser played by William H. Macy whose temperament was particularly suited to “cooling” the luck of gamblers at a casino operated by Alec Baldwin. It needs no further encomia from me, but it’s certainly worth seeing. 2006’s Running Scared was a giddy, unapologetically caffeinated action flick that presented creepy child pornographers and a crazy climactic battle on a hockey rink. It was the kind of fun and scruffy and overexcited movie that perhaps comes along once every two years, and it was woefully misunderstood by such humorless snobs as Cynthia Fuchs, Harvey Karten, and Stephanie Zacharek.* Here was a movie that, much like Sin City, reveled in the absurdities of cinematic violence and only hoped that the audience would share in its zaniness. It was the kind of movie that a certain strain of entitled and elitist New York critic could never understand: a much needed corrective to the overrated and overly referential Kill Bill couplet. That Running Scared succeeded as well as it did, despite the potentially disastrous casting of Paul Walker, was to its immense credit. (And it’s worth noting that even Andrew Sarris wasn’t immune to Running Scared‘s over-the-top charms.)

But I’m sad to report that Kramer’s latest film, Crossing Over, doesn’t share these savage charms. There are two very funny scenes: one intentional and one unintentional. An Australian Jew who is far from faithful attempts to convince a federal agent of his religiosity so that he can secure a visa. A rabbi is enlisted to supervise, to ensure that he’s properly carrying out the kaddish. Not only is the Australian clearly unqualified, but he demands that the agent put his hands against his head in deference. The rabbi, hardly a dummy, gives the agent an okay, hands the Australian a business card, and tells the Australian that he expects to see him in his synagogue tomorrow. It’s a scene that’s vintage Kramer. A moment that defies our expectations and gives us something slightly absurd but believable. Unfortunately, later in the film, we encounter, shortly after a convenience store shootout, one of the most preposterous monologues I think I’ve seen in a movie in some time, in which a man attempts to persuade a young hood that citizenship was “the most spiritual moment of my whole life.” Even the austere crowd at the screening I attended couldn’t stop themselves from howling during this ineptly directed moment.

All this is in service of a Serious Story. There’s an immigration problem in Los Angeles. One that this movie won’t solve. It’s Serious. So Serious that immigration agent Max Brogan (Harrison Ford) can be seen staring into a television downing a glass of scotch as the camera dollies around his lonely and dumpy home in full Hollywood cliche. (A cat enters the frame of the first establishing shot, but the feline is never seen again. Presumably, Brogan was so miserable that he was forced to kill the cat.) But Brogan is driven by that audience-tested commodity of white liberal guilt. What could have been an intriguingly contrarian take on a morally-minded immigration agent caught in a corrupt system (and possibly a thespic comeback for Ford) becomes a formula no different from any other Ford hero. It’s so bad that one expects Ford to boom “Get out of my sweatshop!” in true Air Force One style.

(A few words on Harrison Ford: There was a time in the mid-1980s when Ford took on interesting roles in such films as The Mosquito Coast, Witness, and Frantic. He managed to shed the Han Solo/Indiana Jones image and demonstrated, at long last, that he was a surprisingly versatile actor. Alas, he returned to the money-making roles. So if you’re hoping that Crossing Over represents a return to these halcyon days, you’re probably going to be as disappointed as I was. It doesn’t help that Ford mangles his Spanish. Here’s a man who’s been on the beat for decades. You’d expect a guy of this type to possess some reasonable fluency. But, alas, as an actor, Harrison Ford has become a lost cause. I’m convinced that there isn’t another great performance in him, unless a ballsy director whips him into shape.)

Ray Liotta, who is looking more and more like George W. Bush with each role, is also in this film. He’s a guy on the inside who offers carnal quid pro quos to any hot babe willing to get on all fours for a visa. Liotta, who has this troubling acting tic of keeping his mouth slightly agape, is okay. But that’s only because Alice Eve is utterly amazing in this movie. Like any good actor, she plays not to serve any dormant solipsistic needs, but to keep the scene going. And she saves Liotta’s ass. Her character is an aspiring actress who wants to get ahead but who needs visa status. If this role were played by any other actor, this archetype would have easily transformed into a cliche. But Eve conveys such an accurate sense of removal and a quiet sense of horror when she’s trapped in sleazy motel rooms that she manages to add an emotional quality that this film is sadly lacking. (One wonders what Kramer could get out of Eve if he returned to the quirky sensibilities he established in his two previous films.)

Alas, this is a Serious Story. One in which the feds predictably intercede when a young woman (horribly played by Summer Bishil) delivers a controversial essay before a class about the 9/11 hijackers. (In 2009, the class still resorts to calling her a “sand nigger.” Which leads one to wonder: How long had this script been sitting in Kramer’s drawer? The IMDB, of which more anon, informs us that Kramer made a short film called Crossing Over in 1996. Oh, that explains it.) One in which Ashley Judd (married to Liotta in this) begs her husband to help her out. (She’s an immigration rights attorney.) Too bad that Judd contributes very little to the story. Should I mention the ridiculous brother-sister subplot, with the sister perceived as slutty? Probably not.

At times, this film is so hackneyed that one is tempted to momentarily hold up Crash as a Babel or Touch of Evil comparative point. It wrangles too many storylines and feels utterly phony in its sentiments. Which is too bad. Because this is the first film I’ve seen in which a law enforcement agent actually quotes the Internet Movie Database as an authority. And what is Phil Perry doing in this singing the national anthem? You can take the filmmaker out of the quirks, but you can’t take the filmmaker out of the quirks. Too bad these incongruities aren’t enough.

What the hell has happened to Kramer? Has he been led down an incompatibly damning mainstream path by the take-no-chances producers Frank Marshall and Kathleen Kennedy? Did superstar Harrison Ford demand script changes? Ford’s possibly exorbitant salary appears to have debilitated Kramer’s ability to provide the punchy and moody visuals observed in his two previous films. There is a slapdash and predictable feel to the editing. Every new scene is intercut with rote helicopter shots of the Los Angeles skyline and various interchanges, as if this second-unit footage is supposed to serve in lieu of a proper master shot.

I certainly hope that the title doesn’t apply to Kramer. If Kramer simply wanted to try out a Serious Story, he’s permitted one fumble. We’ll forgive him this dog and hope that he returns to form with the next. But if he has permanently crossed over into pedestrian filmmaking, then this would be grounds for deportment from the pantheon of lively filmmakers to keep tabs on.

* — An update on Saturday morning: Harvey Karten has written to me personally to assure me that he is not a snob. Rather mysteriously, he insists that he’s humorless. I will take his word on these two points, but I am not entirely convinced that he is entirely humorless and will conduct investigations to see if he is capable of blowing a raspberry or two. I am also willing to overturn my assertion about Cynthia Fuchs, should someone present compelling evidence. Zacharek, however, is beyond the point of no return, as her arrogant and uninformed remarks in this article indicate.

Huston: Sometimes, if you use the same words, you can put a little tinkle of irony into it. In the fact that you describe him doing it exactly the way the person just told him. So you use the exact same words. It’s hard for me to answer questions about the writing that are that precise. Because so much of the process is not that precise for me. So much of it is shoveling. And you’re not too terribly conscious of how you shovel while you’re doing it. Whether you’re good at it or not.

Huston: Sometimes, if you use the same words, you can put a little tinkle of irony into it. In the fact that you describe him doing it exactly the way the person just told him. So you use the exact same words. It’s hard for me to answer questions about the writing that are that precise. Because so much of the process is not that precise for me. So much of it is shoveling. And you’re not too terribly conscious of how you shovel while you’re doing it. Whether you’re good at it or not.

Correspondent: Which number is your favorite? Or maybe one of your five favorite numbers?

Correspondent: Which number is your favorite? Or maybe one of your five favorite numbers?

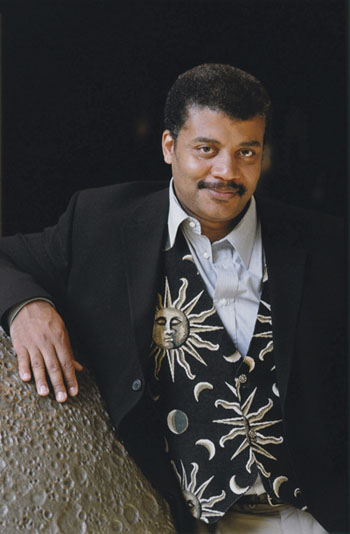

Tyson: We just reorganized the solar system, combining objects of like properties together. And at the time, more frozen bodies — small with tipped orbits, crossing the orbits of other planets — were found in the outer solar system that looked more like Pluto. And Pluto looked more like them than any one of them looked like anything else in the solar system. So all we did was group Pluto with its brethren in the outer solar system. Then we grouped the gas giants together as a family. Then we grouped the terrestrials — Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars — together. So the family photo of the solar system was presented in these groupings. At no time did we recount the planets in the solar system. And, in fact, the word “planet” is undervalued in the exhibits entirely. We prefer to focus on physical properties of these objects, rather than try and salvage a word that hasn’t been formally defined since before Copernicus.

Tyson: We just reorganized the solar system, combining objects of like properties together. And at the time, more frozen bodies — small with tipped orbits, crossing the orbits of other planets — were found in the outer solar system that looked more like Pluto. And Pluto looked more like them than any one of them looked like anything else in the solar system. So all we did was group Pluto with its brethren in the outer solar system. Then we grouped the gas giants together as a family. Then we grouped the terrestrials — Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars — together. So the family photo of the solar system was presented in these groupings. At no time did we recount the planets in the solar system. And, in fact, the word “planet” is undervalued in the exhibits entirely. We prefer to focus on physical properties of these objects, rather than try and salvage a word that hasn’t been formally defined since before Copernicus.

Now imagine living a life, like Elizabeth Gilbert,

Now imagine living a life, like Elizabeth Gilbert,

Beginning on March 2, 2009, this website will be kickstarting a lengthy roundtable discussion of Eric Kraft’s Flying over the course of the week. (For those hoping to follow along with the discussion, this is the same week that the book comes out.)

Beginning on March 2, 2009, this website will be kickstarting a lengthy roundtable discussion of Eric Kraft’s Flying over the course of the week. (For those hoping to follow along with the discussion, this is the same week that the book comes out.)

The morning started off with Bob Stein, founder and co-director of

The morning started off with Bob Stein, founder and co-director of