All together, it was the face of a man to be afraid of in a dark alley or lonely place. And yet Tom King was not a criminal, nor had he ever done anything criminal. Outside of brawls, common to his walk in life, he had harmed no one. Nor had he ever been known to pick a quarrel. He was a professional, and all the fighting brutishness of him was reserved for his professional appearances. Outside the ring he was slow-going, easy-natured, and, in his younger days, when money was flush, too open-handed for his own good. He bore no grudges and had few enemies. Fighting was a business with him. In the ring he struck to hurt, struck to maim, struck to destroy; but there was no animus in it. It was a plain business proposition. Audiences assembled and paid for the spectacle of men knocking each other out. The winner took the big end of the purse. When Tom King faced the Woolloomoolloo Gouger, twenty years before, he knew that the Gouger’s jaw was only four months healed after having been broken in a Newcastle bout. And he had played for that jaw and broken it again in the ninth round, not because he bore the Gouger any ill-will, but because that was the surest way to put the Gouger out and win the big end of the purse. Nor had the Gouger borne him any ill-will for it. It was the game, and both knew the game and played it.”

— Jack London, “A Piece of Steak”

Month / July 2009

Cruel Economy

“Hello there. Sorry to bother you, but I won the Nobel Prize for Physics last year. I’m wondering if you have any temp work.”

“Well, we’re always filling positions.”

“Great! I was just looking for something to get by for a few weeks. Is there anybody I could speak to? I’d be delighted to meet with you. I’m happy to take any typing or computer tests.”

“Do you have any experience?”

“I spent ten years studying the symmetry of extended tachyon-based objects. My findings are being taught in several upper-division classes. But, you know, forget all that. I’m happy to work in the filing room. I just need a few weeks of work.”

“Well, I’m sorry. As you know, it’s been much slower than usual.”

“But I thought you said you were filling positions.”

“We’re always filling positions.”

“I have letters of reference from Michio Kaku and Neil deGrasse Tyson, and I graduated within the top 1% of my class.”

“Yes, that’s nice. Just email us your resume, and we’ll contact you in three weeks if you qualify.”

“My rent is due in three weeks, and I have no savings.”

“It was a pleasure chatting with you! I’m sure you’ll do just fine. A talented guy like you? Just hang in there and stay the course. Prosperity is just around the corner! And never shake the audacity of hope!”

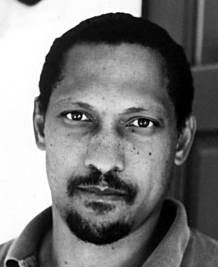

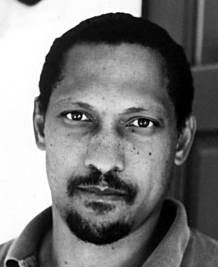

The Bat Segundo Show: Percival Everett

Percival Everett appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #295.

Percival Everett is most recently the author of I Am Not Sidney Poitier.

[For related links, check out Percival Everett Week over at Emerging Writers Network, as well as my specific thoughts about Everett’s most recent novel.]

Condition of Mr. Segundo: He is not Percival Everett.

Subjects Discussed: Name-related jokes, puns and internal metaphors, the many ways to pronounce “Le-a,” literal misunderstandings, whether there really is a Ted Turner, Bill Cosby’s Pound Cake speech, Richard Power’s Generosity, the relationship between reality and fiction, truth vs. reality, the “magic” of writing, stress, on not paying attention to the publishing industry, making the next book, not caring about the reader, on not writing commercial successes, the impulse to entertain, Everett’s world of Dionysus, reader reactions and interpretations, having no affection for previous books, becoming a better writer, the “experimental” nature of Wounded, outlandish one-dimensional figures and subdued prose, I Am Not Sidney Poitier as a “novel of ideas,” on not knowing how to write a novel, artistic creation and gleeful sabotage, narrative worlds and anarchy, Everett’s novels as concrete recreations, loving children geniuses and idiots alike, worldbuilding, subverting subjective character understanding, limitations, writing novels as a playground, having an interest in religion while remaining an “apath,” psychics for horses, believing with character belief, laundry list descriptions, strategic use of language, the relationship between story and language.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: I recently read Richard Powers’s forthcoming novel, Generosity, which deals with the notion of what a novel really is and what ideas and characters really are. And I’m very curious to put this question to you. To what degree do you need reality to start from? And to what degree do you feel the need to be faithful to reality? Or even faithful to real-life figures? Or can you accept a Percival Everett figure in this who also happens to have a book called Erasure?

Correspondent: I recently read Richard Powers’s forthcoming novel, Generosity, which deals with the notion of what a novel really is and what ideas and characters really are. And I’m very curious to put this question to you. To what degree do you need reality to start from? And to what degree do you feel the need to be faithful to reality? Or even faithful to real-life figures? Or can you accept a Percival Everett figure in this who also happens to have a book called Erasure?

Everett: First, I owe nothing to reality. But, of course, for any novel to work, in spite of my disregard — maybe even my disdain for facts — truth is important. If it’s not true, you can’t stay with it. You won’t believe it. And there is no work. But truth has nothing to do with reality or facts.

Correspondent: But you do have names to draw from. Not just in this book, but also in your previous books. Thomas Jefferson, Strom Thurmond. You’re a guy who likes real names like this. And so, as such, I have to ask. Is it just a constant influx of information from newspapers that is your creative muse? Where do you stop from reality and start with the inventive process? Or the misunderstandings we’re talking about?

Everett: Well, it depends on the work. But I read all the time. So it just depends on what comes to me. Some figures just present themselves as too alluring to ignore. How could I go through my life and not at some point address Strom Thurmond? (laughs)

Correspondent: Yeah. Sure. But it can’t just be a simple impulse. Because obviously…

Everett: Why not?

Correspondent: Because I’m thinking when you set out to write a novel — and I’m not you obviously — but when you set out to find a concept or put your finger on something, is it a matter of instinctively knowing that that’s something to riff on or something to expand further? Or do you have any plan like this?

Everett: Sometimes I don’t have a plan. Sometimes it’s hit or miss. Trial or error. Feast or famine. All of those duals. I don’t know. For me, the way novels come together is magic. And I only question it so much.

Correspondent: Magic. Magic through pure work? You’re a prolific guy.

Everett: Yeah, I suppose. Yeah. It won’t get done unless I do it. So I try to do it. And I don’t stress.

Correspondent: You don’t stress? Never stressed at all?

Everett: I try not to be. There’s no reason to get upset about anything. Especially work. And then it happens. And the more it happens, the less stressed I become.

BSS #295: Percival Everett (Download MP3)

Amazon Presents The Great Gatsby

In my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave me advice that I’ve been turning over in my mind since. “Bounty! The quicker picker-upper.”

“Whenever you feel like criticising any one,” he also told me, “just remember a little dab’ll do ya and all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had. Think different.”

He didn’t say any more, betcha can’t eat just one, but we’ve always been unusually communicative in a reserved way, and I understood that he meant a great deal more than that. Sometimes you feel like a nut, sometimes you don’t. In consequence, I’m inclined to reserve all judgments, please don’t squeeze the Charmin’, a habit that has opened up many curious natures to me and also made me the victim of not a few veteran bores. Make a run for the border. The abnormal mind is quick to detect and attach itself to this quality when it appears in a normal person, an army of one, and so it came about that in college I was unjustly accused of being a politician, because I was privy to the secret griefs of wild, unknown men. Screw yourself. IKEA. Most of the confidences were unsought — R-O-L-A-I-D-S spells relief — frequently I have feigned sleep, preoccupation, or a hostile levity when I realized by some unmistakable sign that Ivory, it floats! An intimate revelation was quivering on the horizon — it’s not TV, it’s HBO — for the intimate revelations of young men or at least the terms in which they express them are usually plagiaristic and marred by obvious suppressions. American Airlines. You’re going to like us! Reserving judgments is a matter of infinite hope. I’d walk a mile for a Camel. I am still a little afraid of missing something if I forget that, as my father snobbishly suggested, and I snobbishly repeat a sense of the fundamental decencies is parcelled out unequally at birth. Diet Pepsi. Same time tomorrow?

And, after boasting this way of my tolerance, I come to the admission that it has a limit. Say it with flowers. Conduct may be founded on the hard rock or the wet marshes but after a certain point I don’t care what it’s founded on. You can be sure of Shell. When I came back from the East last autumn I felt that I wanted the world to be in uniform and at a sort of moral attention forever; I wanted no more riotous excursions with privileged glimpses into the human heart. All the news that’s fit to print. Only Gatsby, the man who gives his name to this book, was exempt from my reaction — Gatsby who represented everything for which I have an unaffected scorn. Reach out and touch someone. If personality is an unbroken series of successful gestures, then there was something gorgeous about him, some heightened sensitivity to the promises of life, as if he were related to one of those intricate machines that register earthquakes ten thousand miles away. Fly the friendly skies. This responsiveness had nothing to do with that flabby impressionability which is dignified under the name of the “creative temperament” — it was an extraordinary gift for hope, a romantic

readiness such as I have never found in any other person and which it is not likely I shall ever find again. It’s everywhere you want to be. No — Gatsby turned out all right at the end; it is what preyed on Gatsby, what foul dust floated in the wake of his dreams that temporarily closed out my interest in the abortive sorrows and short-winded elations of men. Just do it.

(With thanks to Paul Constant for aiding and abetting. Related news here.)

This Too Shall Pass

New Review: I Am Not Sidney Poitier

In today’s Chicago Sun-Times, you can find my review of Percival Everett’s I Am Not Sidney Poitier. And it’s rather fitting that much of my review ended up as a list of rhetorical (and possibly unanswerable) questions.

As it so happens, just after filing the review and being wowed by the book, I learned that Everett happened to be in New York. And I was able to set up a rare interview with him (which will be airing as the next episode of The Bat Segundo Show, to be released very soon). Everett, who has avoided nearly every form of marketing for his books*, and who declared to me that he had no interest in the business of publishing or catering to an audience, identified his book as a “novel of ideas.” But I Am Not Sidney Poitier is also steeped in an old-fashioned sense of humor. Here’s a brief excerpt from the forthcoming Segundo installment, in which Everett explains the relationship between these two concepts:

As it so happens, just after filing the review and being wowed by the book, I learned that Everett happened to be in New York. And I was able to set up a rare interview with him (which will be airing as the next episode of The Bat Segundo Show, to be released very soon). Everett, who has avoided nearly every form of marketing for his books*, and who declared to me that he had no interest in the business of publishing or catering to an audience, identified his book as a “novel of ideas.” But I Am Not Sidney Poitier is also steeped in an old-fashioned sense of humor. Here’s a brief excerpt from the forthcoming Segundo installment, in which Everett explains the relationship between these two concepts:

Everett: There are no rules. I don’t believe in any rules when it comes to fiction. If I can make you believe it, then it’s fair game. Probably when I’m working, if I can make myself believe it, then it’s fair game. Because I don’t know what you’re going to believe. And it depends on the work. A novel like Not Sidney, where much of it is more a novel of ideas and the narrator is of a certain sort, can make bizarre perceptions or representations of the world and have the one-dimensional county of Peckerwood County. Whereas in other works, that simply wouldn’t work. So the work talks to me. The most important part of the story is the story. And I can’t impose my feelings or my desire to write a certain kind of thing that day on it.

Correspondent: But in identifying Not Sidney as a novel of ideas, I would argue — and this is where we get into needless taxonomy arguments. But I should point out that you are essentially saying, “Well, this is a novel of ideas.” And maybe the story itself will matter on some basic entertainment level.

Everett: Oh no. The story still matters.

Correspondent: Okay. But I’m curious how committed you are to this idea of the “novel of ideas.” If it’s entirely a construct, should we believe in it entirely or should we believe in the ideas?

Everett: Well, if I’ve done it right, you should believe in it entirely. And superimposed upon this is the narrator’s concept of this being a story of ideas. But you can’t have — and this is not a rule, but, for me, I cannot have a novel where the story is secondary to anything. The world has to exist. And so I have to make it. And I have to make it believable. How I do that can vary and come across in any different number of trajectories or strategies or whatever.

* — This may answer, in part, Gregory Leon Miller’s query this weekend on why Everett’s work hasn’t received the attention it deserves.

Will Resurface Later

The Bat Segundo Show: Hal Niedzviecki II

Hal Niedzviecki most recently appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #294.

Hal Niedzviecki is most recently the author of The Peep Diaries. He previously appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #47.

[PROGRAM NOTE: At the 24:03 mark, a woman with a laptop demanded that Our Correspondent talk with less vivacity, suggesting that Our Correspondent was talking in a “disturbing” manner. Never mind that people sitting closer to us did not complain and that someone even approached Mr. Niedzviecki after the interview, wishing to know what the book was all about. Never mind that, prior to Mr. Niedzviecki’s arrival at the cafe, Our Correspondent observed said woman needlessly chewing out a happy couple for daring to laugh at a joke. However, in the woman’s defense, it is true that Our Correspondent did become quite excited when talking with Mr. Niedzviecki and perhaps raised his voice just a smidgen and perhaps should be pilloried in some form for daring to express considerable enthusiasm about Niedzviecki’s book. We are very well aware that, due to the present economy, enthusiasm has worked against us when trying to persuade various editors to hire us. And if this strange prohibition keeps up like this, there won’t be any enthusiastic people left working in media. (Indeed, there are some telling signs that the enthusiastic who are gainfully employed are beginning to lose their enthusiasm, and this saddens us.) But we note this incident in the event that listeners are confused as to why Our Correspondent and Mr. Niedzviecki began to talk quieter during the latter half of this program.]

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Considering a few definitions of reality.

Author: Hal Niedzviecki

Subjects Discussed: [List forthcoming]

Correspondent: But you’re assuming that the vulnerability is there because you are inadvertently transmitting information. What if you are cognizant of every single thing that you write? Every single tweet that you post? I mean, I don’t think you quite understood Twitter. I certainly don’t use Twitter in the way that you literally use it — in terms of answering the question, “What are you doing?” A lot of people use Twitter in different ways. I use it to exchange links and to brainstorm with other writers and other thinkers. “Oh, well that’s an interesting thought that you had on this!” And it’s a very valuable tool. In fact, I would say that Twitter is probably responsible for fifty 1,000-word pieces I’ve written in the last year. Or something like that. So I’m saying that it’s not necessarily a bad thing. You’re assuming that everything you’re putting out there is personal. But if you’re careful about the personal, if you’re cognizant about the personal, this shouldn’t even be a problem.

Niedzviecki: Oh sure. Absolutely. That’s all well and good if you aren’t putting personal information online. The fact is that millions of people every day are putting personal information online. And that’s probably the #1 primary use of the Internet right now. So okay, your experience is slightly different.

Correspondent: But you’re saying that personal information is…

Niedzviecki: But that’s not really relevant to the question.

Correspondent: I think it is relevant. Is it perhaps a scenario in which you may be, or any of us may be, overstating the importance of our own personal information? Perhaps it really doesn’t matter. If I go ahead and type in “I had a tuna fish sandwich for lunch,” I don’t think that it’s a betrayal to the corporate empire. You know what I mean?

Niedzviecki: Well, I mean, it’s all gradations. I mean, again, this is a topic that I’m not even that excited about. I’m not incredibly hot under the collar. This is just one aspect of the whole phenomena of peep culture. Which is what I call being peeped by the other. We’re peeping ourselves. You know, we should just back up to the whole beginning of this thing, really. Can we do that?

Correspondent: Yeah.

Niedzviecki: Can we back up to this topic? Let’s do that.

Correspondent: Certainly. But if we want to go to the beginning, I mean, it’s not necessarily contingent on the Internet. People were exchanging information and humiliating before the Internet. As you even point out in the book, there was this notion of gossip. There was this notion of spreading rumors about people. We can even talk about the humiliation videos that you mention in this book. Like, for example, the Star Wars kid. Well, is it worse to have the so-called humiliation through a video as opposed to having somebody pilloried in the town square? “Hey, you’re an adulterer and you’re terrible!” And having people throw tomatoes at them? That, to me, seems worse. If you have to go ahead and do it, you may as well go ahead and do it in the form of a middleman here with the Internet.

Niedzviecki: Well, the Star Wars kid’s choice was not being put in stocks in the town square or being forced to wear the dunce cap around the village versus Internet humiliation. It’s not like there was a choice he had to make, right? He never had a choice one way or the other. The basic premise of the book is that pop culture is shifting to peep culture, and that peep culture is the process by which we garner entertainment through watching other people’s vibes. So in pop culture, we watch celebrities and professional entertainers. And now we have peep culture, where we kind of scroll through other people’s lives in the same way we would scroll through TV shows.

Correspondent: Everybody?

Niedzviecki: Not everybody. But a large majority of people. And we’re moving in, you know.

Correspondent: Well, a large majority. Are we talking 51% or 90%?

Niedzviecki: You know, I couldn’t tell you the exact percentage of people.

Correspondent: I think it’s important to have the exact percentage.

Niedzviecki: Well….

Correspondent: Just to get a sense of how much of an epidemic this is.

Niedzviecki: Uh, I’m not an alarmist. I’m not calling it an epidemic. It’s a cultural shift. What we’re doing is — okay, we want numbers. Then, we’ve got to look at reality television. That’s obviously a big part of this, let’s say. We know that ten million people watched the debut — the series debut — of Jon & Kate Plus 8 recently. Previous to that, there was a record five straight Us Weekly covers featuring their eight kids and their marital problems. Okay, that’s ten million people right there. You’ve got in America — you have another ten million people on Facebook. You’ve got your Twitter users. I don’t know how many of those there are. Of course, these categories naturally overlap. You’ve got your Flickr, your Twitter, your YouTube, your Google. I would say that that it’s hard to imagine too many people whose lives aren’t touched in some way by this move to peep culture. The number of people who are actively posting stuff online about their lives and that material is then being used by others for their amusement. It would be hard to give a precise number, but it is certainly — I’d have to say we’re looking at least half the American population who is involved in this.

Correspondent: Half the American population? ‘Cause you said ten million. And the American population is actually 300 million. So that is actually one…

Niedzviecki: I never said ten million.

Correspondent: You said ten million, for example, for this reality TV show.

Niedzviecki: I said ten million people watch that particular show.

Correspondent: Yeah. Ten million. 300 million people. What about the 290 million other people who…

Niedzviecki: But that’s just one show. Then there’s Facebook and Twitter and Google and blogging and every other thing I could think about.

Correspondent: We’re not even in double digits here percentage-wise.

BSS #294: Hal Niedzviecki II (Download MP3)

Alain de Botton on Responding to Critics

(This is the second of an interconnected two part response involving Alain de Botton. In addition to answering my questions, Alain de Botton was very gracious to send along this essay.)

Technology

Many people are only just waking up to how blurred web technology has made the boundaries between public and private. It used to be easy to know what a public statement was. It was one written for a newspaper or for a radio or television broadcast. But the web has made it harder to discern what is meant to be public and what private. A huge number of people now read newspapers only on the web, alongside other web windows like Facebook, Twitter and blogs. This equalises the difference between the two, it potentially places a Facebook status entry on the same level as the headline of the foreign affairs section of the New York Times. Simply on the basis of visual appearance, on your screen, there is no difference between the might and authority of a comment in the New York Times, and a note written in a blog run from the proverbial bedroom.

So it becomes hard, as a reader, to measure the degree of intent behind any statement one reads — and as a writer, it becomes hard to judge how seriously one’s words are going to be taken and how large the audience for them will be.

How to review a book

Mr. Crain reviewed my book for The New York Times on Sunday 28th June, 2009. The book was accorded a full page review, a relatively rare honour, and was the third review to run in the pecking order. In other words, this was a prestigious slot in the most prestigious paper in the largest book market on the planet. The power of the New York Times in the world of books can’t be overestimated. A review in the paper can close down a book or make its fortunes. With books pages being cut right across the world, it remains the authoritative place for information.

Given this power, the onus on any reviewer is to use it wisely, a wisdom to which there is no finer guide than John Updike and his six rules of reviewing as laid out in his collection Picked Up Pieces. Updike’s concern was for fairness. This did not mean that he wanted every book to be praised. Rather, he wanted every book to be given it’s ‘fair due’. The end of a fair appraisal might mean the book was not recommended, but the author and reader could feel that the reviewer had kept his or her side of the bargain. Updike recommended that the reviewer try to understand what the author was up to, enter imaginatively into the project, and most of all avoid any kind of attack that felt ad hominem.

Given this power, the onus on any reviewer is to use it wisely, a wisdom to which there is no finer guide than John Updike and his six rules of reviewing as laid out in his collection Picked Up Pieces. Updike’s concern was for fairness. This did not mean that he wanted every book to be praised. Rather, he wanted every book to be given it’s ‘fair due’. The end of a fair appraisal might mean the book was not recommended, but the author and reader could feel that the reviewer had kept his or her side of the bargain. Updike recommended that the reviewer try to understand what the author was up to, enter imaginatively into the project, and most of all avoid any kind of attack that felt ad hominem.

I have been in the writing business for 15 years and have received many bad reviews. However, when I read Crain’s review, it was apparent that it was unusually uninterested in adhering to Updike’s six golden rules of reviewing.

What can one do with a bad review?

There is no official right of reply to the judgement of reviewers. One cannot sue, complain or do anything that counts. One has two options: stoicism (batten the hatches). Or Christianity (turn the other cheek).

There is a third private option. To write to the reviewer in the hope of giving them a sense of their power and influence — and the effects to which they have used it. The hope is that by doing so, the reviewer may with time come to reflect on the matter and when they are next presented with a book, they may (and this is a very hopeful idea indeed) adhere a little more closely to Updike’s six golden rules.

I hence found my way to my reviewer’s website and there, in what I thought was a comparatively private arena, sent him a message that was deliberately hyperbolic and unstoic, the equivalent of a punch in words. The idea was to reveal honestly what effect he had on me.

The problem with overhearing people in private moments is that they don’t follow the rules of civilised society and hence offend our sense of propriety (that’s why the rules are in place). All of us, if cameras were turned on during our moments of rage, disappointment, fear and vengeance, would wince if the footage were then played back to us or – even worse – were played back to an audience of strangers. We value privacy for precisely this reason: it protects us our immaturities from wider display.

It can be appalling for all concerned if the private spills out – for example, if a guest was listening to a marital argument, both the guest and the marital couple would be appalled.

The reactions of others

My altercation with Caleb Crain has attracted a peculiar amount of interest at heart because its nature as a private communication has been misunderstood, both by me – and those looking on. It has widely been taken that I have written back to The New York Times directly to complain. Instead I wrote to Caleb Crain to speak very directly to him and not principally to the world at large. I feel very sorry that this tiff has been broadcast so widely. The embarrassment is as akin to an argument with one’s spouse being inadvertently broadcast to one’s work colleagues or a private letter appearing on a widely-read internet site.

I have been naive here. My conclusion is that one has to be extraordinarily careful about the internet. Nothing that one types here that others could potentially access should ever be phrased in ways that wouldn’t make one happy if a million other people happened to see it. There should only be measure and reason – or else it will be judged along exactly the same criteria as one would judge an op-ed piece in The New York Times.

I continue to maintain that the subjects of unfair criticism have the right to protest and perhaps in heartfelt ways too – they should simply take extreme care that absolutely no one is watching or recording them doing so.

Alain de Botton Clarifies the Caleb Crain Response

(This is the first of an interconnected two part response involving Alain de Botton. In addition to answering my questions, Alain de Botton was very gracious to send along this essay.)

In last Sunday’s New York Times Book Review, Caleb Crain reviewed Alain de Botton’s The Pleasures and Sorrows of Work. While regular NYTBR watchers like Levi Asher welcomed the spirited dust-up, even Asher remained suspicious about Crain’s doubtful assertions and dense prose.

But on Sunday, de Botton left numerous comments at Crain’s blog, writing, “I will hate you till the day I die and wish you nothing but ill will in every career move you make. I will be watching with interest and schadenfreude.”

But on Sunday, de Botton left numerous comments at Crain’s blog, writing, “I will hate you till the day I die and wish you nothing but ill will in every career move you make. I will be watching with interest and schadenfreude.”

As Carolyn Kellogg would later remark, this apparent enmity didn’t match up with the sweet and patient man she had observed at an event. While de Botton hadn’t posted anybody’s phone number or email address, as Alice Hoffman had through her Twitter account, de Botton had violated an unstated rule in book reviewing: Don’t reply to your critics.

But the recent outbursts of Hoffman, de Botton, and (later in the week) Ayelet Waldman — who tweeted, “The book is a feminist polemic, you ignorant twat” (deleted but retweeted by Freda Moon) in response to Jill Lepore’s New Yorker review — have raised some significant questions about whether an author can remain entirely silent in the age of Twitter. Is Henrik Ibsen’s epistolary advice to Georg Brandes (“Look straight ahead; never reply with a word in the papers; if in your writings you become polemical, then do not direct your polemic against this or that particular attack; never show that a word of your enemies has had any effect on you; in short, appear as though you did not at all suspect that there was any opposition.”) even possible in an epoch in which nearly every author can be contacted by email, sent a direct message through Twitter, or texted by cell phone?

I contacted de Botton to find out what happened. I asked de Botton if he had indeed posted the comments on Crain’s blog. He confirmed that he had, and he felt very bad about his outburst. I put forth some questions. Not only was he extremely gracious with his answers, but he also offered a related essay. Here are his answers:

First off, did you and Caleb Crain have any personal beefs before this brouhaha went down? You indicated to me that you found your response counterproductive and daft. I’m wondering if there were mitigating factors that may have precipitated your reaction.

I have never met Mr. Crain and had no pre-existing views. The great mitigating factor is that I never believed I would have to answer for my words before a large audience. I had false believed that this was basically between him and me.

What specifically did you object to in Crain’s review? What specifically makes the review “an almost manic desire to bad-mouth and perversely depreciate anything of value?”

My goal in writing The Pleasures and Sorrows of Work was to shine a spotlight on the sheer range of activities in the working world from a feeling that we don’t recognise these well enough. And part of the reason for this lies with us writers. If a Martian came to earth today and tried to understand what humans do from just reading most literature published today, he would come away with the extraordinary impression that all people spend their time doing is falling in love, squabbling with their families — and occasionally, murdering one another. But of course, what we really do is go to work…and yet this ‘work’ is rarely represented in art. It does appear in the business pages of newspapers, but then, chiefly as an economic phenomenon, rather than as a broader ‘human’ phenomenon. So to sum up, I wanted to write a book that would open our eyes to the beauty, complexity, banality and occasional horror of the working world — and I did this by looking at 10 different industries, a deliberately eclectic range, from accountancy to engineering, from biscuit manufacture to logistics. I was inspired by the American children’s writer Richard Scarry, and his What do people do all day? I was challenged to write an adult version of Scarry’s great book.

The review of the book seemed almost willfully blind to this. It suggested that I was uninterested in the true dynamics of work, that I was interested rather in patronising and insulting people who had jobs and that I was mocking anyone who worked. There is an argument in the book that work can sometimes be demeaning and depressing — hence the title: Pleasures AND Sorrows. But the picture is meant to be balanced. On a number of occasion, I stress that a lot of your satisfaction at work is dependent on your expectations. There are broadly speaking two philosophies of work out there. The first you could call the working-class view of work, which sees the point of work as being primarily financial. You work to feed yourself and your loved ones. You don’t live for your work. You work for the sake of the weekend and spare time — and your colleagues are not your friends necessarily. The other view of work, very different, is the middle class view, which sees work as absolutely essential to a fulfilled life and lying at the heart of our self-creation and self-fulfilment. These two philosophies always co-exist but in a recession, the working class view is getting a new lease of life. More and more one hears the refrain, ‘it’s not perfect, but at least it’s a job…’ All this I tried to bring out with relative subtlety and care. As I said, Mr. Crain saw fit to describe me merely as someone who hated work and all workers.

Caleb Crain’s blog post went up on Sunday. You responded to Crain on a Monday (New York time). You are also on Twitter. When you responded, were you aware of Alice Hoffman’s Twitter meltdown (where she

posted a reviewer’s phone number and email address) and the subsequent condemnation of her actions?

I was not aware.

Under what circumstances do you believe that a writer should respond to a critic? Don’t you find that such behavior detracts from the insights contained within your books?

I think that a writer should respond to a critic within a relatively private arena. I don’t believe in writing letters to the newspaper. I do believe in writing, on occasion, to the critics directly. I used to believe that posting a message on a writer’s website counted as part of this kind of semi-private communication. I have learnt it doesn’t, it is akin to starting your own television station in terms of the numbers who might end up attending.

You suggested that Crain had killed your book in the United States with his review. Doesn’t this overstate the power of the New York Times Book Review? Aren’t you in fact giving the NYTBR an unprecedented amount of credit in a literary world in which newspaper book review sections are, in fact, declining? There’s a whole host of readers out there who don’t even look at book review sections. Surely, if your book is good, it will find an audience regardless of Crain’s review. So why give him power like that?

The idea that if a book is good, it will find an audience regardless is a peculiar one for anyone involved in the book industry. There are thousands of very good books published every year, most are forgotten immediately. The reason why the publishing industry invests heavily in PR and marketing (the dominant slice of the budget in publishing houses goes to these departments) is precisely because the idea of books ‘naturally’ finding an audience isn’t true. Books will sink without review coverage, which is why authors and publishers care so acutely about them — and why there is a quasi moral responsibility on reviewers to exercise good judgement and fairness in what they say.

The outlets that count when publishing serious books are: an appearance on NPR, a review in the New Yorker and the New York Times Book Review. There are of course some other outlets, but they pale into insignificance besides these three outlets. Of the three, the New York Times Book Review remains the most important.

Hence I don’t for a moment over-estimate the importance of Mr Crain’s review. He was holding in his hands the tools that could make or break the result of two to three years of effort. You would expect that holding this sort of responsibility would make a sensible person adhere a little more closely to Updike’s six golden rules.

In the wake of Updike’s death, partly as a tribute to him, my recommendation is that newspapers all sign up to a voluntary code for the reviewing of books. This will help authors certainty, but most importantly it will help readers to find their way more accurately towards the sort of literature they’ll really enjoy.

If you were to travel back in time on Sunday morning and you had two sentences that you could tell yourself before leaving the comment, what would those two sentences be?

Put this message in an envelope, not on the internet.

Despotism (1946)

“A careful observer can use a respect scale to find how many citizens get an even break. As a community moves towards despotism, respect is restricted to fewer people. A community is low on a respect scale, if common courtesy is withheld from large groups of people on account of their political attitudes, if people are rude to others because they think their wealth and position gives them that right, or because they don’t like a man’s race or his religion. Equal opportunity for all citizens to develop useful skills is one basis for rating a community on a respect scale. The opportunity to develop useful skills is important, but not enough. The equally important opportunity to put skills to use is a further test on a respect scale.”