Caleb Crain’s ego was swelling. He had spent three weeks basking his head in a rare rave from acclaimed author Norman Rush in the New York Review of Books. The New Yorker‘s James Wood had also declared Necessary Errors “a very good novel, an enviably good one.” But this grand and substantive praise from high literary places was not enough for this privileged and priggish 46-year-old Columbia Ph.D., who was spending his Wednesday night acting like an upstart two decades younger, threatening me with a libel suit as I was on a long walk without my phone. The following email arrived in my inbox at 7:01 PM. The subject line was “libel”:

Dear Edward Champion,

It has been brought to my attention that a comment has been falsely posted in my name on your blog, at this address:

http://www.edrants.com/boris-kachka-the-inspector-clouseau-of-cultural-journalism/

I would like you to remove it promptly, and I would like you as the manager of the blog to state clearly that the removed content was a forgery and that you have removed it accordingly.

all best,

Caleb Crain

It has long been the editorial policy of this website to allow comments, even belligerent ones, from pseudonyms. Strangers have left anonymous remarks under the names Billy Joel, Danny DeVito, Joyce Carol Oates, James Wood, and others. Not only do I support the right of commenters to use celebrity names as new forms of Publius, but so does the law. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act grants immunity to online service providers (including website proprietors) when others take action to “restrict access to or availability of material that the provider or user considers to be obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, exceedingly violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable.” This is one of the reasons why so many odious trolls are able to get away with what they do. But the positive side of this is that it allows free expression of unpopular or dangerous ideas: a tenet that I remain fully committed to, especially in an age in which journalists are being increasingly harassed by governments for telling the truth.

The comment in question, attributed to a false “Caleb Crain” and posted here yesterday at 4:01 PM, reads as follows:

Ed Champion, I will hate you till the day I die and wish you nothing but ill way in every career move you make. I will be watching with interest and schadenfreude.

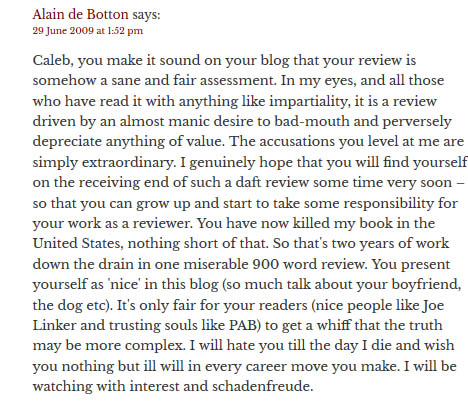

When this comment came in, I instantly recognized this as a riff on Alain de Botton’s infamous comment to Caleb Crain on June 29, 2009:

Alain de Botton had been exceedingly gracious when I asked him about his response to Caleb Crain in July 2009. Not only did he answer my questions, but he contributed an essay on responding to critics. This was the kind of caritas and above-and-beyond munificence that always replenishes my faith in the human race. I had figured that the mysterious comment, originating from an IP address somewhere in New York, had come from an especially devoted reader who was very familiar with my website. I chuckled at the joke and went for my aforementioned long walk.

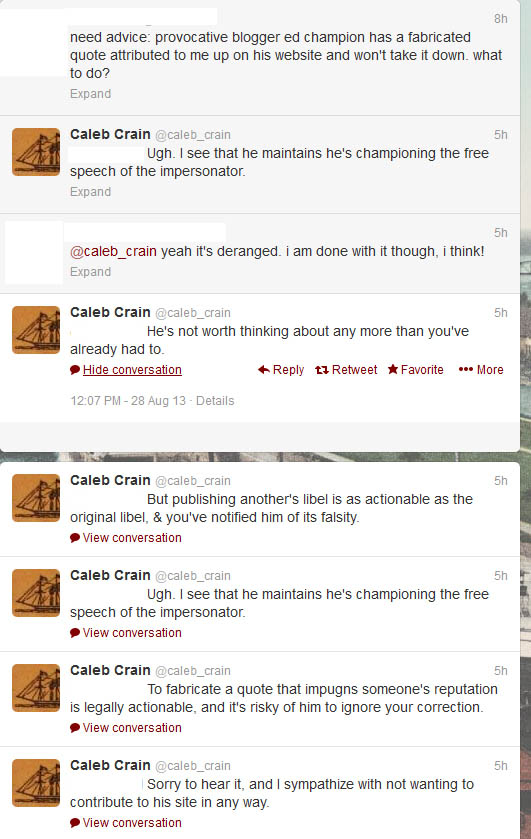

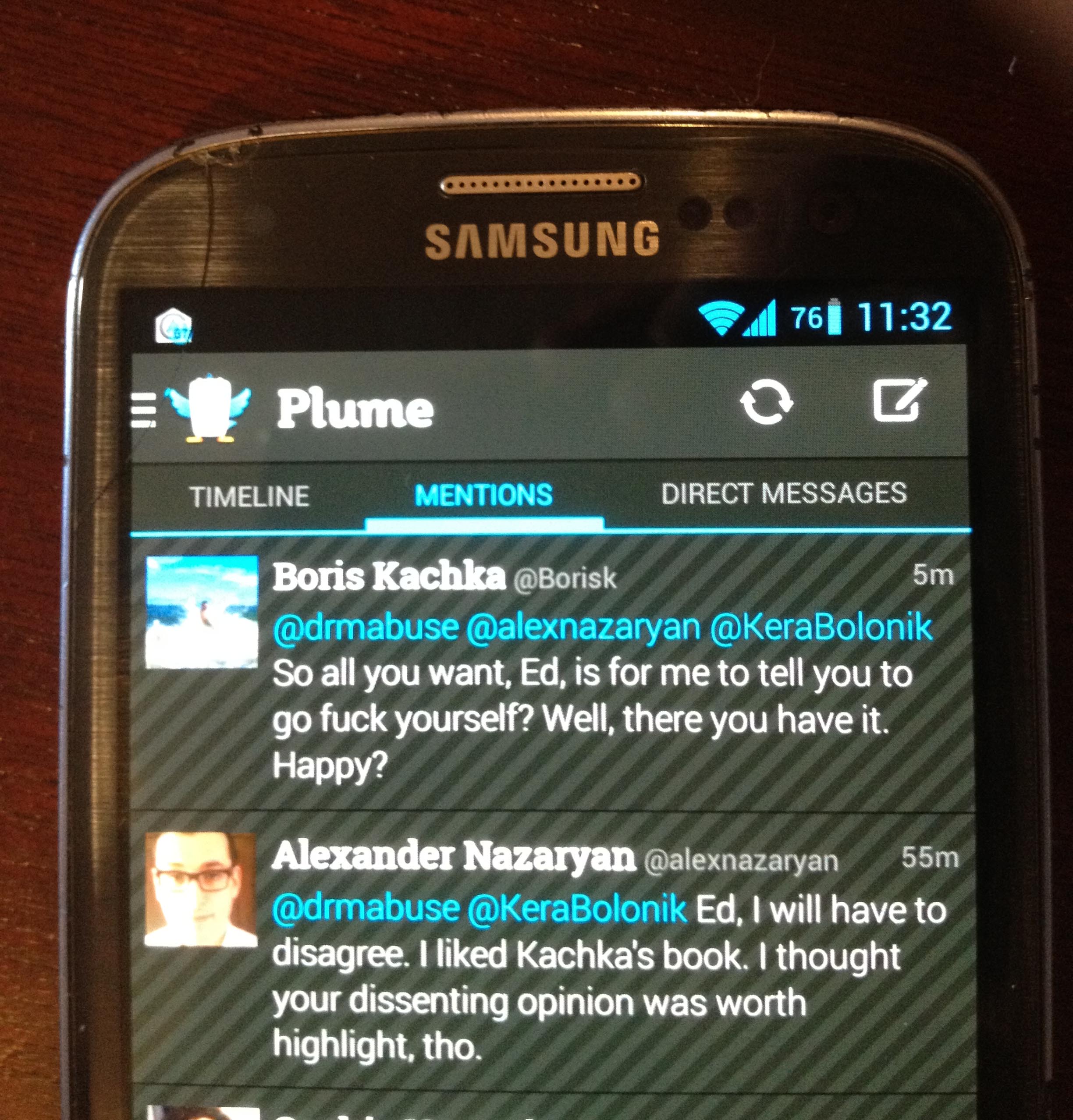

It turned out that Crain had been busy on Twitter that afternoon, corresponding with a Boston Globe employee who had spent the last three weeks harassing my girlfriend and me. (I have blanked out his name because I do not want to give this very angry and embittered young eunuch any further attention. But let’s call him Lee Siegel — no relation to the cultural critic.)

Lee Siegel had sent me several rude, belligerent, and unprofessional emails over the past six months — some from his Boston Globe account, in direct contravention of Section A1 of the Globe‘s Journalism Ethics Policy. He had called my writing “psychotic” and declared on February 26, 2013 (after I offered to answer a question in his capacity as reporter), “Man. Literally every single thing you say is embarrassing.” Siegel emailed me on May 9th on another matter he wanted to know about. By then, I had tired of his flaccid pugnacity. I would not answer any further questions from him. I replied:

Lee:

As far as I’m concerned, you’ve burned me as a source for life. Given our last exchange, you’ll never get answers from me on any subject ever again. And given what I have going, it’s your loss, not mine. Let this be a professional lesson.

Sincerely,

Ed

Siegel replied:

Haha, OK — this wasn’t about sourcing. It’s just that I got an email about a piece from another total monster with the last name Champion, and wanted to know if you two were part of the same family. Would have been hilarious to me if you were.

Good luck with what you have going!

Lee

Given such churlish behavior, I wondered if Siegel had ever bothered to read the Globe‘s very sensible ethical code:

We treat audience members no less fairly in private than in public. Anyone who deals with our public is expected to honor that principle, knowing that ultimately our readers are our employers. Civility applies whether an exchange takes place in person, by telephone, by letter or by e-mail.

On August 3, 2013, I published a lengthy essay pointing to misogyny, unsubstantiated rumors presented as fact, and incompetent journalism in Boris Kachka’s Hothouse. I learned later that the piece was disseminated in certain circles populated by both Siegel and Caleb Crain. And because many of these pathetic creatures never seem to leave the house, do not appear to have lives beyond the digital, have capitulated all that remains of their curiosity and wonder for snark and solipsism, demonize people they have never met, never ruminate on vital subjects such as Syria or income inequality or surveillance or anything substantial, and spend most of their free time on Twitter “hate-favoriting” tweets, they have always been very easy to ignore. Because they have little more than passive-aggressive ire, a paucity of conviction, and limitless free time to offer a complicated and turmoiled world

However, someone from an IP address in Massachusetts, left the following comment under Lee Siegel’s name:

A woman kissed you? Is that, like, the first time that has ever happened to you? Did you jizz?

As we have established, as website owner, I am not the one fabricating the quote and I am also immune from liability thanks to the CDA. I am thus under no obligation to remove the quote, any more than The Onion (a far more powerful outlet than mine) should be prevented from publishing pieces “written” by Joyce Carol Oates or CNN’s Meredith Artley. Indeed, unlike Crain or Siegel, Artley responded to the parody with characteristic grace:

@socialnerdia @TheOnion I'm reading it as more of a joke than something to call the legal team about.

— Meredith Artley (@MeredithA) August 26, 2013

Lee sent me two emails in less than 24 hours. The second email read:

Ed — did you receive the below? The comment attributed to me still appears at the bottom of your psychotic rant about Boris Kachka, and you ought to remove it.

Lee

Here’s a modest diplomatic tip for young whipper-snappers: if you want to work with someone, it is probably not in your best interest to call the other person “psychotic,” especially after you have already sent several vituperative emails.

Lee then sent the following email to my girlfriend:

Hey there. I am hoping you can help me with a problem I’m having with Ed. A vulgar comment was posted underneath this post on his website by someone pretending to be me, and I need it to be taken down. Lord knows I would not hesitate to ridicule Ed in public, but in this particular case, it so happens that someone is impersonating me.

I have contacted Ed about this, but he has not responded, presumably because we despise each other. Can you please talk to him?

Here’s another modest diplomatic tip: if you want to reach someone through their loved one, it is probably not in your best interest to pledge public ridicule towards the mind you’re trying to change, much less adopt a haughty tone rarely seen outside of Frances Hodgson Burnett novels.

In the spirit of fairness, I decided to contact Lee’s girlfriend, who I’ll call Becky Sharp. We had a civil and polite email colloquy. As I had long suspected, she was clearly the more fair-minded and smarter of the pair. I suggested that Lee should leave a followup comment to clear up the matter. This is precisely what James Wood did in a thread at The Millions. This is indeed what adults do.

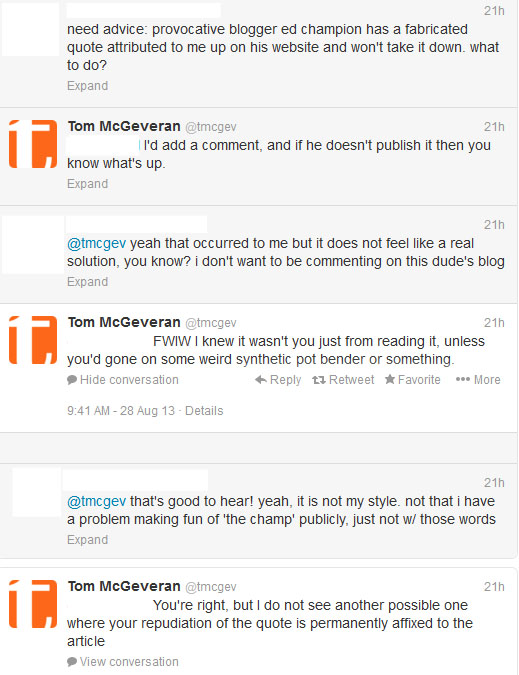

Lee did not take up this advice and continued to email me. Because Lee was too stupid to comprehend how content management systems worked, he contacted WordPress, who told him rightly that there was nothing they could do. And even as he angrily flailed with endless ignorance, Lee adamantly refused to leave another comment on the thread (“But I don’t think that would solve my problem — or yours, since right now you have what amounts to a fabricated quote from me on your site.”).

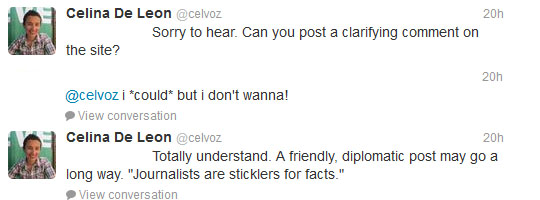

Like many attention-starved megalomaniacs, Lee took to Twitter, soliciting advice. Most of the people who responded to Lee on Twitter, including Capital New York co-editor Tom McGeveran and social media coordinator Celina De Leon, sensibly informed him that leaving another comment would settle the matter. But like a petulant and coddled child, Lee replied, “i *could* but i don’t wanna!”

Aside from the civilized exchange I had with Becky Sharp, the one guy who was a class act during this mess was London Review of Books editor Christian Lorentzen, a friend of Siegel who stepped in as a diplomat. I informed Lorentzen by direct message and in the thread about what was going on and why I could not remove the comment, but thanked him for his gesture.

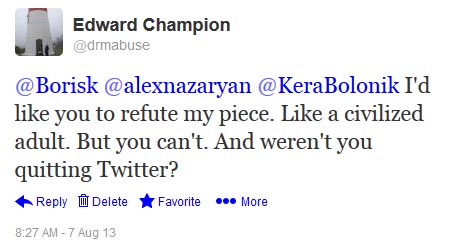

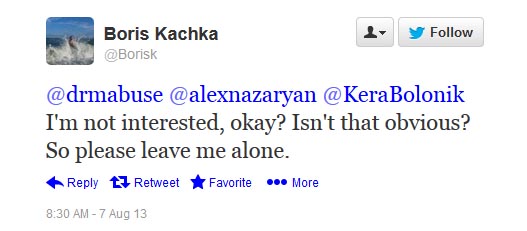

It was at this point that Caleb Crain stepped into the Twitter conversation with Siegel. This was followed by the fake “Caleb Crain” comment that was left here on Thursday afternoon.

When I returned home from my saunter, I responded to Caleb as follows:

Dear Caleb:

I have just returned from a very long walk and have just received your email. I have also witnessed your behavior on Twitter. You are absolutely out of line, both here and on Twitter. You have NOT been libeled. And I am ccing your publicist on this so that she knows how you are spending your free time. So that Lindsay has some sense of how you are behaving, I have attached a screenshot of your Twitter antics this afternoon.

My girlfriend and I have been severely harassed by Lee Siegel. I had a perfectly civil exchange with Lee’s girlfriend, Becky Sharp, suggesting that Lee leave a followup comment, which I would happily approve. My commenting policy is to allow anyone to post under any pseudonym. Lee chose not to exercise that option. Christian Lorentzen also civilly stepped in. And I explained the situation to him.

You, of course, decided to spread misinformation about this. Without contacting me. You were grossly irresponsible. Then some individual, who I presume observed what was happening on Twitter, left a jokey comment under your name. It’s absolutely clear with the phrasing that he’s referencing Alain de Botton’s reaction to your hostile review, published on this page on June 29, 2009 at 1:52 PM.

http://www.steamthing.com/2009/06/review-of-alain-de-bottons-pleasures-and-sorrows-of-work.html

It’s clear to me that this comment is a joke, a defensible parody. Your reputation is clearly not at stake here: an absolute blip at best, compared to Joyce Carol Oates or Meredith Artley, who were the targets of more mean-spirited parodies in a more powerful venue (the Onion). Over the years, people have left comments at my site as James Wood, Joyce Carol Oates, Billy Joel, Danny DeVito, and numerous others. I have never had anyone complain until now. If you would like to clarify that it’s not you in the thread, as James Wood once did at the Millions, feel free and I will approve it. That’s a perfectly reasonable response. (Indeed, this is what was suggested to Lee by several journalists.)

However, I will not remove the initial “Caleb Crain” comment. That you and Lee cannot leave a followup comment clearing this up, something that takes all of 15 seconds, says to me that you and he are more interested in perpetuating a phony conflict with me.

Understand that I am very committed to free speech. I am also very familiar with libel law and have beaten SEVERAL very high-profile legal challenges to my website over the years. You do not have a case. But if you want to try, be my guest. You would have to prove that the comment falls under the four elements of libel. Honestly, it would be much easier for you to be an adult and leave a followup comment or laugh the whole thing off. The latter option is often what people who have a sense of humor do. I am sorry to learn of your humorlessness.

You’ve got raves from James Wood and Norman Rush and THIS is how you’re spending your time? Seriously?

I demand a public apology for your misleading tweets. If you do not do so by 11:00 AM EST tomorrow, I will go public with your baseless threats. But obviously I would prefer not to.

Sincerely,

Edward Champion

As I composed the above email, Crain sent me a more threatening one, ccing his literary agents Jacqueline Ko and Sarah Chalfant. I did not see this email until after I had sent my reply.

Dear Mr. Champion,

Two different people have contacted me in the past few hours in the belief that the comment falsely posted in my name on your blog was in fact by me. In other words, the comment is not being perceived as parody. There is no free speech defense for libel. Please understand that I take this with the utmost seriousness.

I must also ask you to retain a record of internet protocol addresses and any other metadata associated with the comment falsely posted in my name, as well as associated with the comment posted under your name above it, because information about these two comments may be required by me in a future lawsuit. This information is ordinarily visible to you, as the manager of the blog, in the management panes of your blog software. I am not asking you to disclose it publicly but merely to retain it for discovery.

Sincerely,

Caleb Crain

First off, Crain is not a lawyer. He has not cited any cases or statutes, much less established a case for libel. His colossal hubris in demanding privileged information and claiming discovery, especially since he clearly does not understand legal procedure, is that of a pampered parvenu who has perhaps watched a few too many episodes of Law and Order. Crain has always had the option to leave a followup comment to resolve any confusion he claims from “two different people.” But much like his braying compadre Lee Siegel, Crain could but he don’t wanna.

I’d like to point out that, until all this, nobody had ever written to me — in a little under a decade of online existence — to complain about a fabricated comment.

But Caleb Crain and Lee Siegel both believe they are above the law, that they are above parody and free expression. And they are so wild-eyed and consumed with arrogance that they cannot deign to either laugh off the joke or leave a followup comment in the thread.

On Thursday morning, Crain’s agent, Sarah Chalfant, sent the following email to me just before my 11AM deadline:

Dear Mr. Champion,

I am writing on behalf of Caleb Crain, further to his and your emails of yesterday evening. We are hoping that we can all move beyond this discussion, and wanted to reach out to suggest the following: Caleb will delete his tweets about his interaction with Lee, if he could, in turn, publish a comment on your blog stating that “As will be obvious to anyone who knows me, I did not write the comment above, which has been falsely posted in my name,” for which we’d be grateful.

Caleb would certainly agree not to make any further public statements in blog posts, interviews, and elsewhere about this interaction, if you would be willing to agree to the same; I hope this sounds right to you.

I look forward to hearing from you.

My best,

Sarah Chalfant

This was a fair and professional response. I replied minutes later:

Sarah:

Thank you very much for your email. This is exactly what I requested and is eminently reasonable. As I have declared all along, Caleb has always been free to leave whatever comment he wishes, no matter the tenor. I would also appreciate if he could publicly apologize for his behavior on Twitter. I will, in turn, publicly commend Caleb for his good grace and we will never speak of the matter again.

I’m glad that we could resolve this in an amicable fashion. Please let me know if there’s anything else that you or Caleb would need of me.

All best,

Ed

I also informed all parties that I would extend the 11AM deadline to 2:00 PM to give Crain ample time to meet the terms of this resolution.

But Crain has done nothing. He has not left a comment in the thread. He has not apologized. He has not removed the tweets.

So Crain has forced my hand. It has become necessary to expose him as a pompous and privileged prick. I invite Caleb Crain to sue me for libel, but I’d much rather see him apologize. As Alain de Botton noted of Crain four years ago, Crain is clearly driven by an almost manic desire to badmouth and deprecate and accuse rather than resolve an issue. Maybe Crain’s ire should be directed at the gormless tot who I’ve named Lee Siegel, the sad young literary man and washed up reporter who was so consumed with bile that he was prepared to waste the time of friends, girlfriends, literary agents, literary publicists, and readers — all because he could not find one small scrap of humility. It’s also too bad that Crain has revealed himself to be a solitary man weeping on a bench, his mouth as helpless and ugly as an embryo chicken. Perhaps he should read Auden closer.