“You gotta understand. The Internet is like a giant, weird orgy where like everything gets shared. A lot of people are using stuff that I make. And every time that I make a photo and I put it out there, it gets reblogged on a million sites, and I would never put my name on it. ‘Cause we’re like all in this giant — it’s kind of like we’re all on ecstasy at a giant rave.” — Josh Ostrovsky, after being asked by Katie Couric about his plagiarism

Josh Ostrovsky is an unremarkable man who has built up a remarkable fan base of 5.7 million Instagram users by stealing photos from other sources without attribution under the handle The Fat Jew, claiming the witticisms as his own, and turning these casual and often quite indolent thefts into a lucrative comedy career. His serial plagiarism, which makes Carlos Mencia look like an easily ignored bumbling purse snatcher, has understandably attracted the ire of many comedians, including Patton Oswalt, Kumail Nanjiani, and Michael Ian Black. The ample-gutted Ostrovsky transformed his gutless thieving into a deal with Comedy Central (since cancelled by the comedy network), CAA representation, and even a book deal. Ostrovsky is an unimaginative and talentless man who believed he could get away with this. And why not? The unquestioning press fawned over the Fat Jew at every opportunity, propping this false god up based on his numbers rather than his content. While the tide has turned against Ostrovsky in recent days, the real question that any self-respecting comedy fan needs to ask is whether they can stomach supporting a big fat thief who won’t cut down on his rapacious stealing anytime soon.

Ostrovosky’s lifting has already received several helpful examinations, including this collection from Kevin Kelly on Storify and an assemblage from Death and Taxes‘s Maura Quint. But in understanding how a figure like Ostrovsky infiltrates the entertainment world, it’s important to understand that, much like serial plagiarists Jonah Lehrer and Q.R. Markham, Ostrovsky could not refrain from his pathological need for attention.

After a two day investigation, Reluctant Habits has learned that every single Instagram post that Ostrovosky has ever put up appears to have been stolen from other people. His work, his lies, and his claims were not checked out by ostensible journalists, much less corporations like Burger King hiring this man to participate in commercials and product placement that he was compensated for by as much as $2,500 a pop.

In an interview with Katie Couric earlier this year, Ostrovsky offered some outright whoppers. Ostrovsky, who claimed to be “such a giver,” presented himself as a benign funnyman who said that “it’s just my gift” to find photos and apply captions to them. Tellingly, Ostrovsky declared, “It’s the only thing I can do in this world.”

“A lot of stuff I actually make myself,” said Ostrovsky. “Like sometimes if you see a tweet from like DMX, you know, or some kind of hardcore rapper being like, ‘About to go antiquing upstate,’ like ‘I’m refinishing Dutch furniture,’ like he probably didn’t write that. I Photoshopped that.”

Actually, the sentiment that Ostrovsky ascribed to DMX (assuming he didn’t pluck the image from another source) on April 14, 2015 (“YEAH SEX IS COOL BUT HAVE YOU EVER HAD GARLIC BREAD”) had actually been circulating on the Internet years before this. It started making the rounds on Twitter in November 2013 and appears to have been plucked from a now deleted Tumblr called whoredidthepartygo. This tagline theft is indicative of Ostrovsky’s style: take a sentence that many others have widely tweeted, reapply it in a new context, and hope that nobody notices.

The Couric interview also contained this astonishing prevarication:

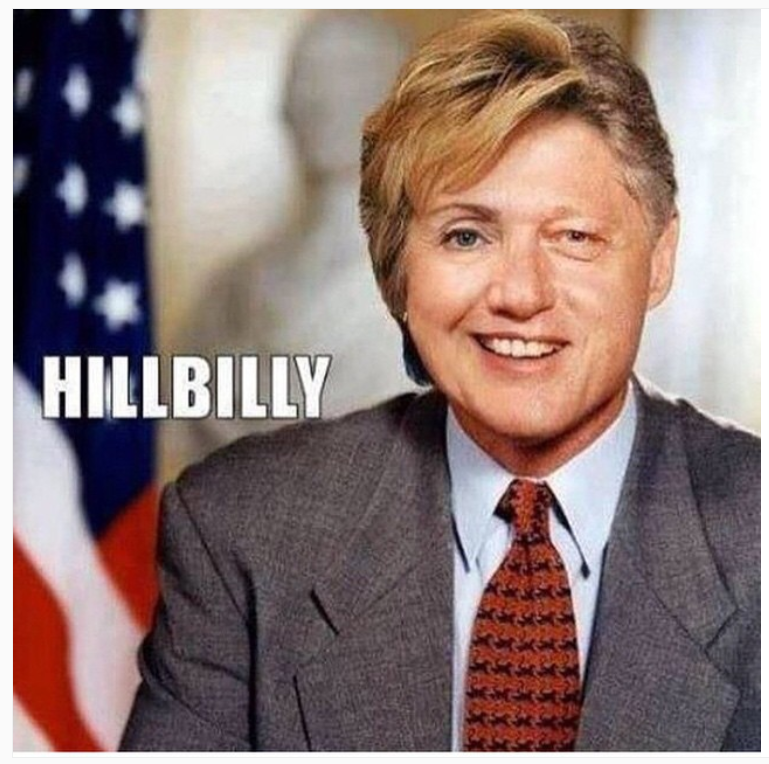

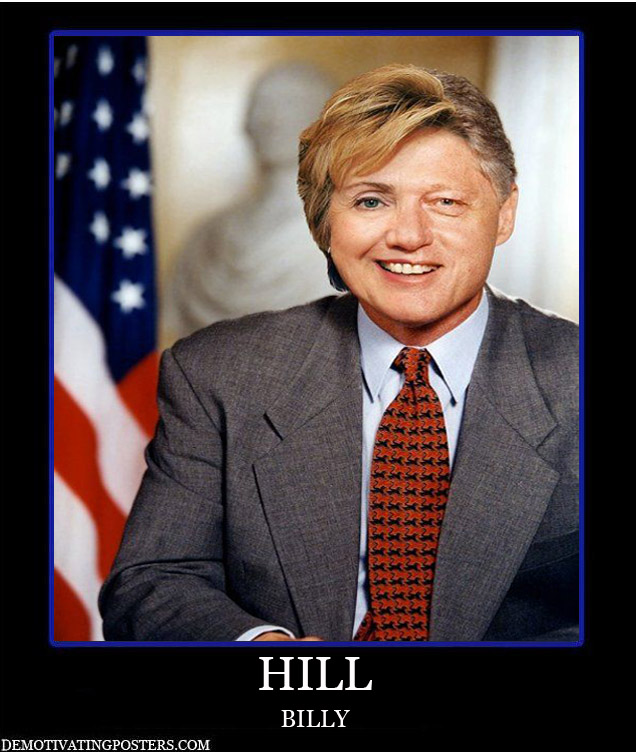

Couric: I like Hillbilly too. You took half-Hillary, half-Bill Clinton.

Ostrovsky: Yup. A friend of mine actually made that and like just really exploded my brain into like a thousand pieces.

If this is really true, then why did Ostrovsky wait four years to share his “friend”‘s labor? Especially since it had “exploded his brain into like a thousand pieces.” After all, doesn’t a giver like Ostrovsky want to act swiftly upon his “generosity”? The Hillbilly pic was posted to Ostrovsky’s Instagram account on January 7, 2015.

But this image was cropped from another image that was circulating around 2011 — nearly four years before. If Ostrovsky’s “friend” gave the Hillbilly photo to him, then why was it cropped, with the telltale link to demotivatingposters.com (a now defunct link) elided?

Reluctant Habits has examined Ostrovsky’s ten most recent Instagram posts. Not only are all of his images stolen from other people, but Ostrovsky often did not bother to change the original image he grabbed. In some cases, it appears that Ostrovsky simply took a screenshot from Twitter, often cropping out the identifying details.

For the purposes of this search, I have confined my analysis to any photo that Ostrovsky uploaded with a tagline. As the evidence will soon demonstrate, not only is Ostrovsky incapable of writing an original tag, but he appears to have never written a single original sentence in any of his Instagram captions.

I have included links to Ostrovsky’s Instagrams and the original tweets. But I have also taken screenshots in the event that either Ostrovsky or his originators remove their tweets.

OSTROVSKY INSTAGRAM 1: August 16, 2015.

SOURCES OF PLAGIARISM:

As if to exonerate himself from the theft, Ostrovsky’s Instagram post included a callback to Instagram user @pistolschurman, who posted it onto Instagram that same day. One begins to see Ostovsky’s pattern of behavior: bottom-feed from a bottom-feeder.

But the image had already been widely distributed on Twitter with the tagline, “The international symbol for ‘what the hell is this guy doing?’,” “The international symbol for ‘what the hell is this douchebag doing?,” and “The international symbol for what the fuck is this nigga doing?'” But have traced its first use on Twitter to Betto Biscaia on August 10, 2014:

OSTROVSKY INSTAGRAM 2: August 16, 2015.

SOURCE OF PLAGIARISM:

On August 16, 2015, the user @tank.sinatra posted this to Instagram, failing to acknowledge the original source. Ostrovsky linked to @tank.sinatra.

This was first tweeted by user @GetTheFuzzOut on August 14, 2015.

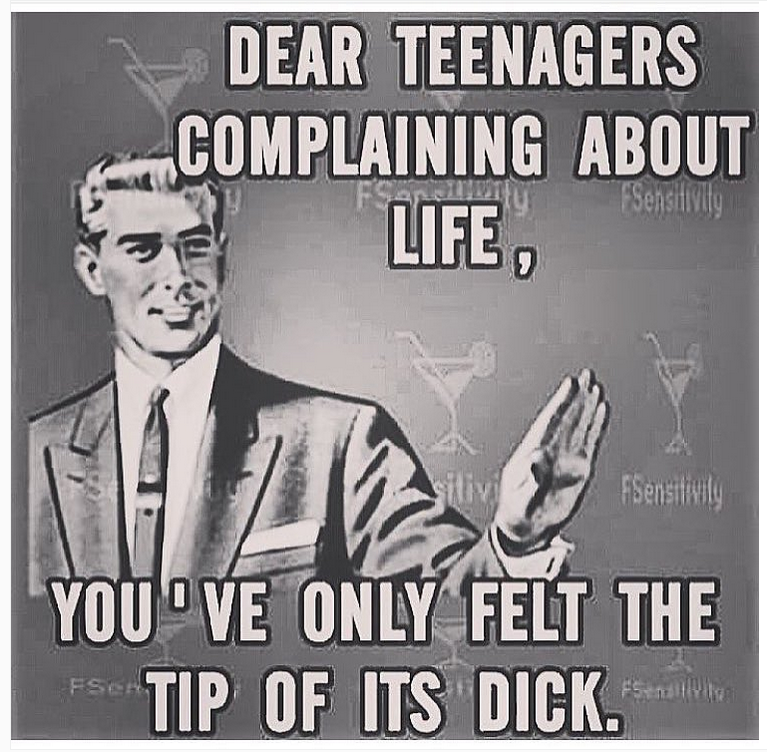

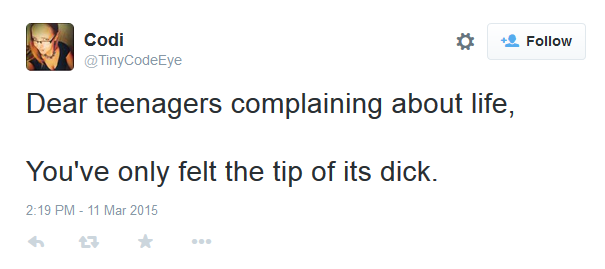

OSTROVSKY INSTAGRAM 3: August 14, 2015

SOURCES OF PLAGIARISM: While it appears that Ostrovsky or one of his minions may have typed the sentiment upon a new image, a Google Image Search shows that this sentence has been widely attached to photo memes. The first use of the joke on Twitter appears to originate from @TinyCodeEye on March 11, 2015.

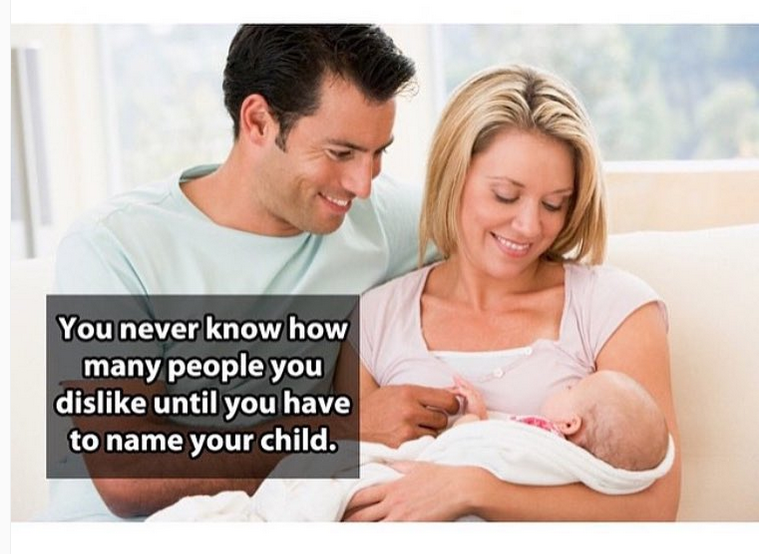

OSTROVSKY INSTAGRAM 4: August 14, 2015

SOURCES OF PLAGIARISM: This has been a long-running tagline/photo combo, but Ostrovsky didn’t even bother to swap the font for this photo. The tagline appears to have been added to the photo for the first time by user @ViralStation on July 17, 2015:

In other words, Ostrovsky was so slothful in his theft that he couldn’t even be bothered to generate a new image.

As for the tagline context itself, I have traced its first use on Twitter to hip-hop artist EM3 on July 14, 2015:

I have reached out to EM3 on Twitter, asking if he was the first person to take this photo. He responded that he did not take the photo, but that he plucked it from eBay. (The latter response may have been facetious.) What EM3 may not know is that his quip was stolen by Ostrovsky and monetized for Ostrovsky’s gain.

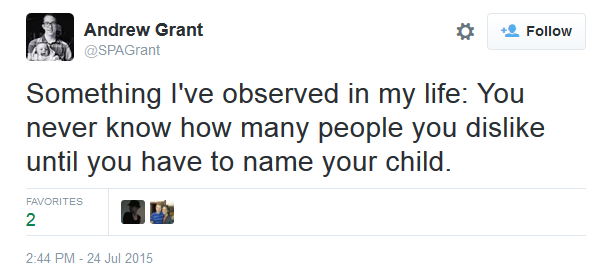

OSTROVSKY INSTAGRAM 5: August 14, 2015

SOURCES OF PLAGIARISM: The joke was first tweeted by Andrew Grant on July 24, 2015.

But Grant, in turn, stole the joke from a Reddit thread initiated by user youstinkbitch on July 10, 2015.

OSTROVSKY INSTAGRAM 6: August 14, 2015

SOURCES OF PLAGIARISM: The photo/tag combo appears to originate with user @FUCKJERRY, who tweeted this on July 2, 2015.

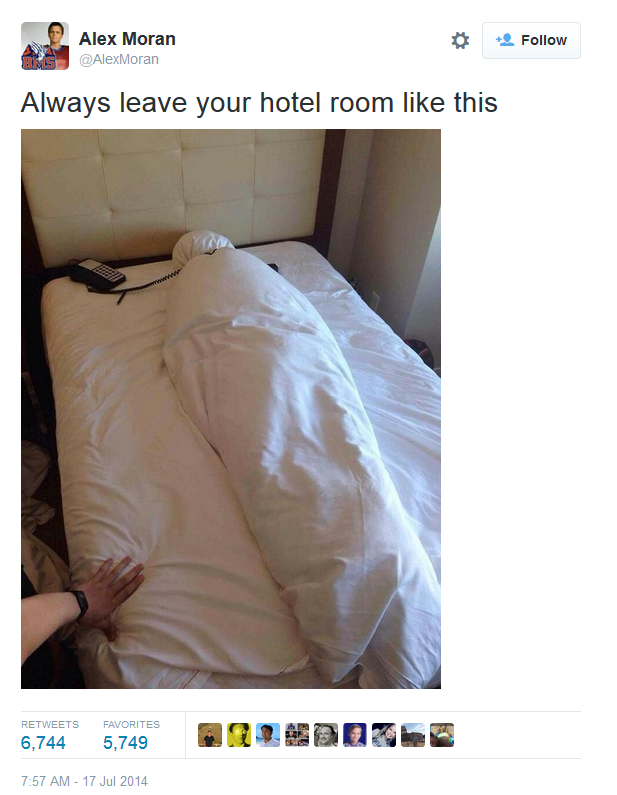

OSTROVSKY INSTAGRAM 7: August 14, 2015

SOURCES OF PLAGIARISM: This was among the oldest tags I discovered and quite indicative of the desperate thieving that Ostrovsky practices. It appears to originate from Alex Moran, who tweeted it on July 17, 2014.

I have reached out to Mr. Moran to ask him if he was the person who snapped the photo. He has not responded.

OSTROVSKY INSTAGRAM 8: August 13, 2015

SOURCE OF PLAGIARISM: This was first tweeted by user @natrosity on November 5, 2014.

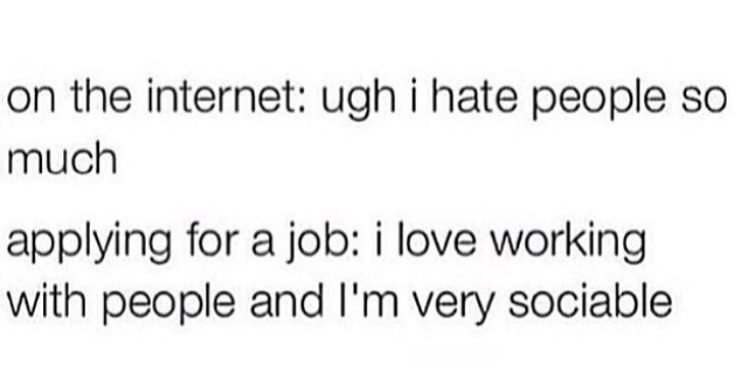

OSTROVSKY INSTAGRAM 9: August 13, 2015

SOURCE OF PLAGIARISM: This joke has become so widely circulated that only the world’s worst hack would use it. Ostrovsky thinks so little of his audience that he’s circulating a joke that’s been around since at least August 2012, when it first started appearing Tumblr. The first Twitter link to this is from August 2, 2012:

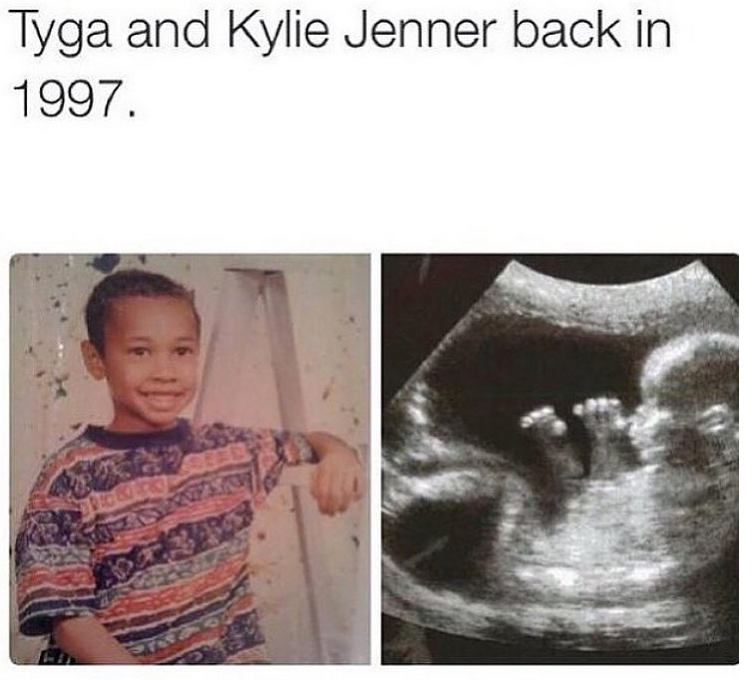

OSTROVSKY INSTAGRAM 10: August 13, 2015

SOURCE OF PLAGIARISM: The source of this appears to come from a now-defunct Tumblr called Luxury-andFashion. The earliest mention on Twitter appears to be on November 12, 2014 — a link to its Tumblr distribution.